Need weekend plans?

The best things to do around the city, delivered to your inbox.

“Boston Strangler,” Hulu’s new true crime movie, examines the infamous 1960s murders through the eyes of two reporters who helped to bring the case to the public’s attention.

This isn’t the first time Hollywood has taken a look at the killing spree that rocked Boston in the 1960s, during which 13 women were murdered between June 14, 1962, and January 4, 1964. The 1968 film “Boston Strangler,” starring Henry Fonda as the lead investigator and Tony Curtis as suspected Strangler Albert DeSalvo, debuted to generally positive reviews.

Unlike that film, however, 2023’s “Boston Strangler” doesn’t hew to the conventional wisdom of the era, which pinned every single murder tangentially connected to the case on DeSalvo. Instead, “Boston Strangler” digs deeper, unearthing facts that may be common knowledge for people who lived through that era but will be new information for millions of viewers.

Director Matt Ruskin, who grew up in Watertown, admitted that the particulars of the case weren’t familiar to him when he began researching the project.

“Growing up in Boston, I think everybody had heard of the Boston Strangler,” Ruskin told Boston.com. “But it wasn’t until I started reading about the case that I realized I really knew nothing about the story.”

To bolster his knowledge, Ruskin dug through years of old newspaper clippings and books, consulted family members of those involved in the case, and listened to archival interviews with Loretta McLaughlin, a former reporter for the Boston Record-American who serves as the protagonist of “Boston Strangler.”

Though Ruskin was careful with his attention to detail, there are moments in the film where he felt comfortable taking small amounts of dramatic license to serve the film.

“One of the things that really drew me to this story was just how many unexpected twists and turns there were to it,” Ruskin said. “I couldn’t make this stuff up, and so I didn’t. That said, there’s always liberties that you have to take when you want to tell a story in two hours. So we compress time in certain places, and of course, dramatize things that maybe in reality are a bit of an oversimplification.”

To help viewers understand more about the people on-screen in “Boston Strangler,” we took our own dive into the archives of the Boston Record-American and The Boston Globe to better understand the facts and the people involved with the Boston Strangler case.

The three journalists primarily featured in “Boston Strangler” were all based on real-life employees of the Boston Record-American.

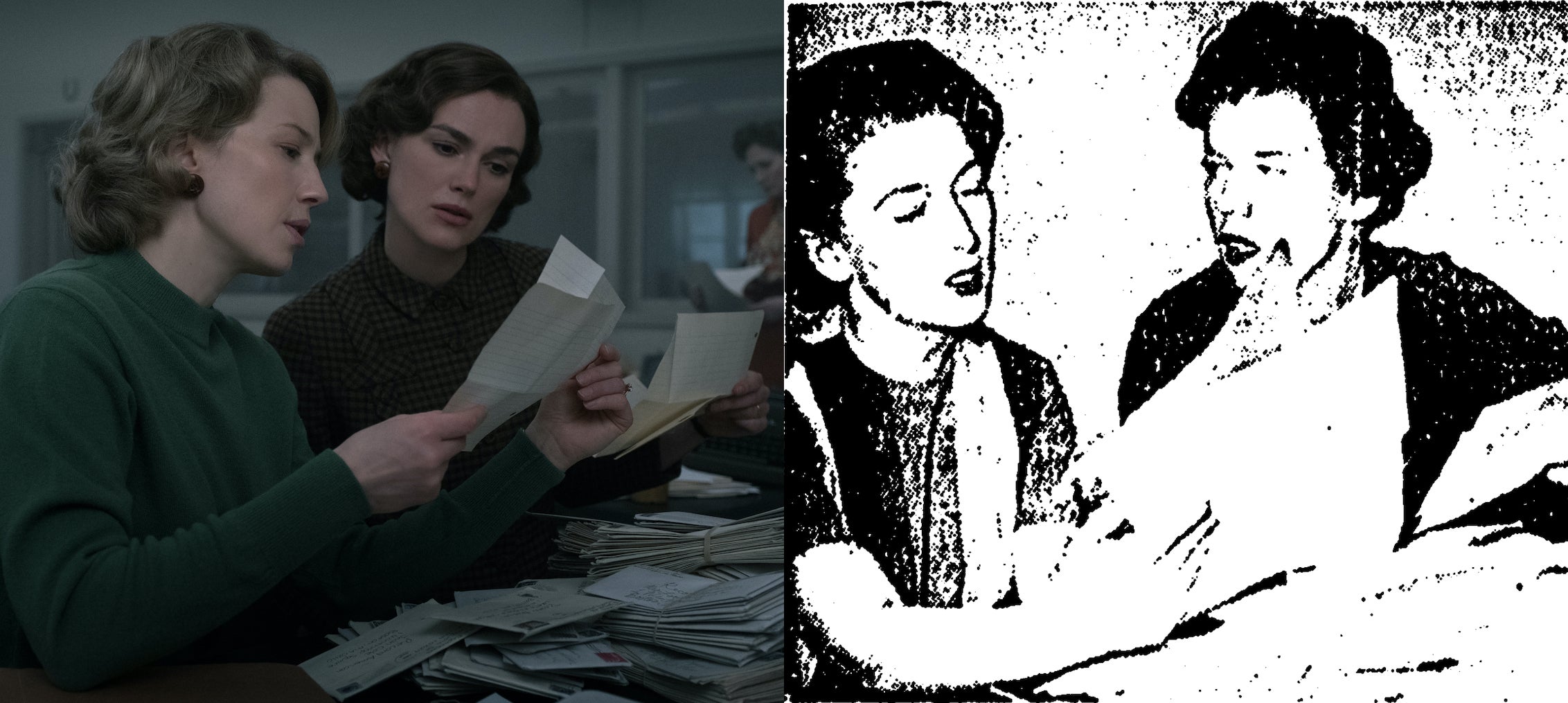

Loretta McLaughlin, played by Keira Knightley, was a reporter at the Record-American, and along with Jean Cole, wrote the definitive account of the case and coined the “Boston Strangler” moniker. After working at the Record-American, McLaughlin later worked at The Boston Globe from 1976 until her retirement in 1993.

In the film, Loretta is seen begging city editor Jack MacLaine (Chris Cooper) to let her investigate a possible connection between the crimes. But Jack dismisses her, saying she’s on the lifestyle desk.

In the documentary “Boston Strangler Revisited” (available for free on YouTube), McLaughlin confirmed that she went to MacLaine, who rebuffed her request to investigate the deaths by calling the women “nobodies,” a phrase Cooper also uses in the film.

“An editor disputed the worth of a series on the four dead women, noting that they were ‘nobodies,’ ” McLaughlin wrote in the Globe in 1992. “That was it exactly, I felt. Why should anyone murder four obscure women. That was what made them so interesting […] sisters in anonymity, like all of us.”

To prepare for the role, Cooper told Boston.com that he spoke to former Globe journalist Eileen McNamara, whom McLaughlin mentored at the Globe in the ’70s and ’80s.

“They were terribly dismissive of a woman journalist,” Cooper said. “Eileen said all the editors would have their whiskey in the lower drawer. It was not really a comfortable atmosphere for women to be in.”

It was also true that McLaughlin wrote a number of lifestyle pieces during her time at the Record-American and its predecessor. “Blonde Likes Laughs, Brunette Likes $$$” read one 1952 McLaughlin headline about the marriage preferences of Boston-area women.

That said, McLaughlin was no stranger to the crime beat by the time the Boston Strangler case came to prominence. She had covered murders and courtroom dramas throughout the 1950s at the Boston American, usually with a sensational, tabloid-ready hook. In 1953, McLaughlin wrote of Mildred McDonald, a 25-year-old Somerville woman who walked into the home of her ex-boyfriend and shot his 14-year-old sister.

Shortly after the Boston American and the Daily Record merged to form the Boston Record-American in October 1961, McLaughlin was one of several reporters to write extensively about the still-unsolved disappearance of Joan Risch, a housewife in Lincoln who left behind a trail of blood and a mountain of questions.

Another shortcut used by “Boston Strangler” occurs shortly before McLaughlin is paired with Cole on the Strangler stories. While the film implies the pair have never met, McLaughlin and Cole actually began working together even before they started at the Record American. In April 1952, when Cole was at the Boston Daily Record, she and McLaughlin worked together on a presidential poll that forecasted a big win for Dwight D. Eisenhower in Massachusetts. The pair show up together as subjects in stories as well, with the duo helping organize a Press Club party for a retiring editor in December 1952.

There are two Boston Police figures who feature prominently in “Boston Strangler,” one of which is based on a real figure and one who is a composite of multiple real-life BPD officers.

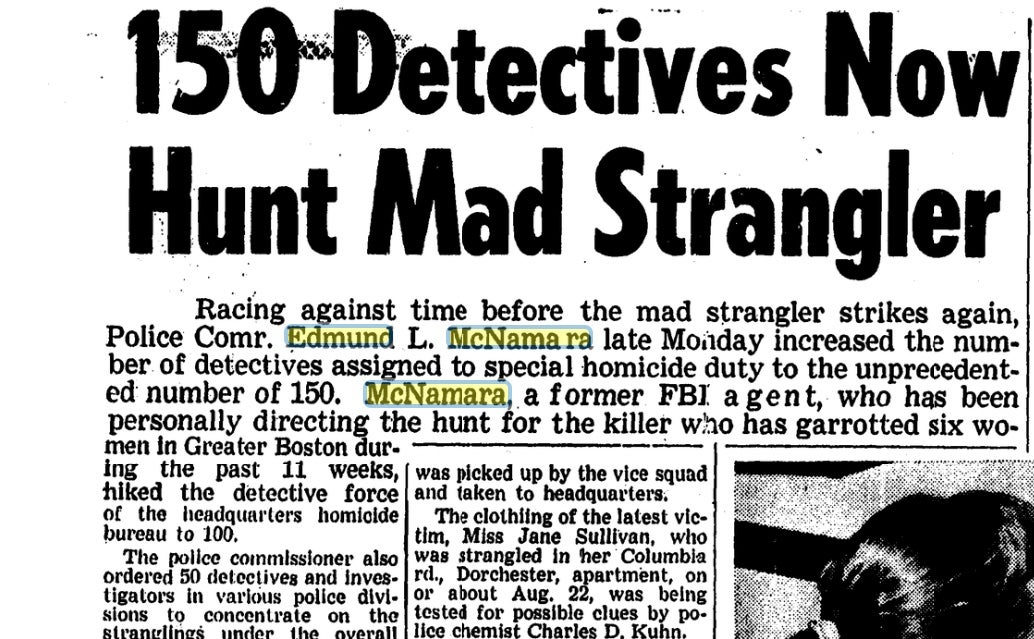

After McLaughlin publishes her first story, her editor catches hell from BPD Commissioner Edmund McNamara, who is played by Massachusetts native Bill Camp (“Joker”). In real life, McNamara was just starting the first year of a five-year term when the Strangler stories began percolating in 1962. McNamara initially garnered positive headlines for his diligence on the case, with the Record-American noting that he had assigned 150 detectives to the case in September 1962. By early 1963, however, public sentiment seemed to turn, with a Record-American article saying that “neither Police Comr. McNamara nor all the King’s horses could placate the victim’s neighbors” after yet another killing.

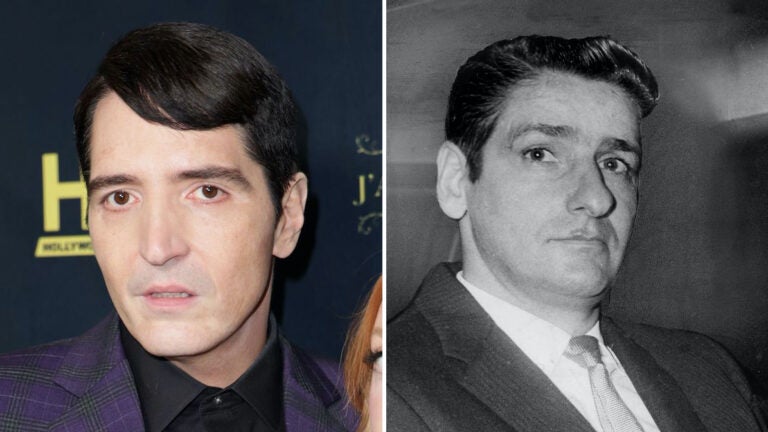

In the film, McLaughlin is aided by a sympathetic figure in BPD Detective Conley, a fictional character played by Boston native Alessandro Nivola. Nivola, who doesn’t naturally speak with a Boston accent but capably pulls it off in the film, told Boston.com that he watched a police interrogation of the Craigslist Killer to prepare for the film, and basically imitated the detective from that investigation.

“It was actually the first time I’d ever really listened to a real police interrogation start to finish,” Nivola said. “It’s so brilliant the way that they kind of led him through it and put him at ease and, you know, got him off guard.”

Much like in real life, the ending of “Boston Strangler” doesn’t come to any tidy conclusion about who was responsible for the killings. In the film, we see three men who are held up as possible suspects, two of whom existed in real life and one who is a pseudonymous creation.

Albert DeSalvo, played by David Dastmalchian (“The Dark Knight”), confessed to all 13 of the killings. But he was never convicted of those killings due to a deal struck by his attorney, F. Lee Bailey. The deal said that DeSalvo would be sentenced to life in prison for the multiple rapes he allegedly committed, but his confession to being the Boston Strangler would not be admissible in court.

DeSalvo was later stabbed to death in prison in 1973. Robert Wilson, an inmate associated with Whitey Bulger’s Winter Hill Gang, was put on trial for DeSalvo’s murder but not convicted.

In 2013, DNA evidence linked DeSalvo to the 13th and final killing in the Boston Strangler case, but the other 12 remain officially unsolved.

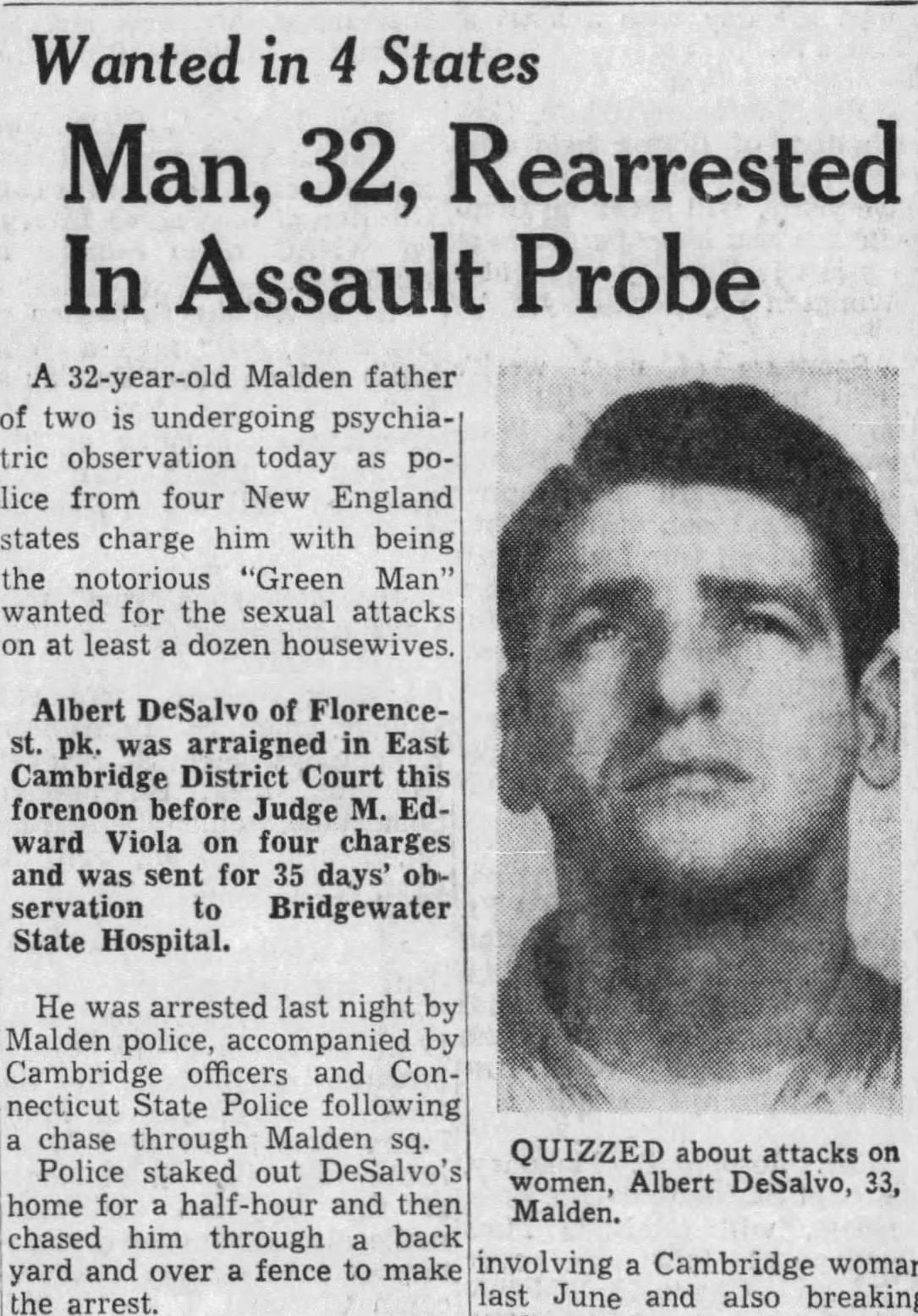

DeSalvo had a troubled upbringing and was a subject in a decades-long Harvard University study about the causation of criminality in youth. DeSalvo was regularly beaten by his father and was first arrested at age 12. DeSalvo was arrested for a series of break-ins and assaults on young women in 1964, fitting the description of a serial rapist the press dubbed the “Green Man.”

While at Bridgewater State Hospital, DeSalvo met fellow inmate George Nassar, who was awaiting trial for murdering a gas station owner. Nassar then reached out to his attorney, F. Lee Bailey, who began meeting with DeSalvo before brokering his confession.

“Boston Strangler” also spends time with another alleged suspect, known as “Daniel Marsh.” Marsh did not exist in real life, but instead represents the many men who were at one point strongly considered to be the Strangler. Poring over the Record-American at the time, there are countless articles that speculate about suspects in the slaying.

Controversially, Massachusetts Attorney General Edward Brooke paid noted psychic Peter Hurkos to use ESP to identify a suspect. A 1964 Record-American story tells of Hurkos touching crime scene objects and using ESP to identify an unnamed 57-year-old suspect who Brooke said matched the description of a “prime suspect” in the case.

Hurkos, who was paid handsomely for his efforts, also later affirmed the possibility that another of Brooke’s unnamed suspects was the culprit, whose biographical details match Marsh in the film: A Harvard-educated man who spent time at Bridgewater at the same time as DeSalvo and Nassar, and was briefly suspected of a series of murders in Michigan that also involved stockings and sexual assaults.

While “Boston Strangler” doesn’t provide any definitive answers, it does illustrate how several people close to the case, as well as many amateur sleuths in the present day, have unanswered questions. It also relies on theories put forth in the intervening years that have never been definitively proven.

“Boston Strangler” speculates that George Nassar was initially motivated by reward money for information leading to the Boston Strangler, while DeSalvo was wooed by promises of a book deal. It also speculates that perhaps Nassar himself may have committed some of the killings, and found DeSalvo as a willing scapegoat.

As Dr. Ames Robey, who treated both men at Bridgewater and believed DeSalvo to be innocent, put it, DeSalvo was ”a very clever, very smooth, compulsive confessor who desperately need[ed] to be recognized.”

Thomas Troy, who served as DeSalvo’s attorney after Bailey starting in 1968, said in the documentary “Boston Strangler Revisited” that he believed DeSalvo’s confession was a matter of convenience.

“Boston and the metropolitan area were living in a reign of fear,” Troy said. “People were locking their doors, buying guard dogs.”

“[F. Lee Bailey] cut a deal that no one else could do,” Troy continued. “He said, ‘Don’t use what we tell you in any court of law against my client, and we’ll solve your crimes.’ And solve them he did. The Strangler’s alive and well somewhere, and it’s not Albert DeSalvo.”

In the same documentary, Phil DiNatale, the lead investigator of a Boston Strangler task force, said he believed that DeSalvo, his prime suspect in the case, was guilty. He spoke to DeSalvo numerous times, and said that DeSalvo was able to provide him with intricate details about the case that no one else knew. DiNatale wanted DeSalvo to stand trial as the Strangler, and blamed competing political interests for the ultimate decision to convict DeSalvo on lesser charges instead.

“To this day, people say that he isn’t [the Strangler] — for what reason I don’t know,” DiNatale said. “They can say that he isn’t in one sentence, but I can produce document after document for days and days and show you that he is.”

The best things to do around the city, delivered to your inbox.

Stay up to date with everything Boston. Receive the latest news and breaking updates, straight from our newsroom to your inbox.

Conversation

This discussion has ended. Please join elsewhere on Boston.com