Need weekend plans?

The best events in the city, delivered to your inbox

Joel Christian Gill, the author of the graphic novel series “Strange Fruit” — subtitled “Uncelebrated Narratives from Black History” — originally figured he was working on “funny little comics that I could sell to hipsters.”

“That’s kind of how I thought about it, until I was at my very first book signing in Maine, and this guy came up to me, and he had tears in his eyes,” Gill recalls now. “And he was like, ‘Thank you for telling these stories. These are very important stories.’”

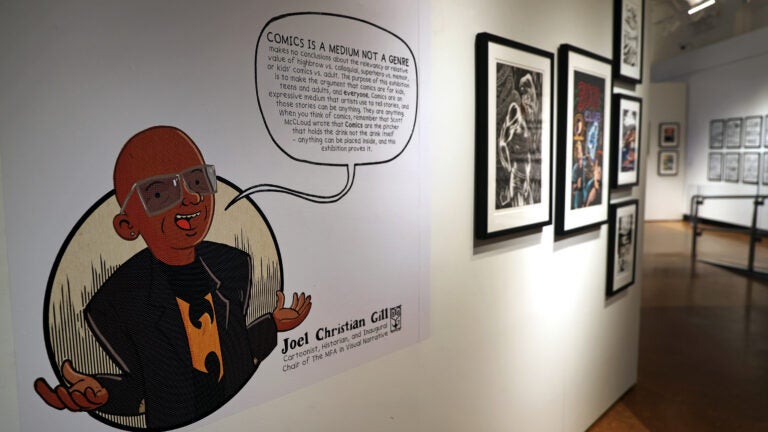

It’s a lesson he’s taken with him in his study of the comics arts and in his role as the inaugural chair of the Master of Fine Arts in Visual Narrative at Boston University, where he earned his own MFA in 2004. He recently curated the exhibit “Comics Is A Medium, Not A Genre,” running through March 24 at the school’s Stone Gallery; it’s a free exhibit that covers a century-and-a-half of American comic books, comic strips, graphic novels, and more, in an attempt to show how comics can tell any kind of story to any age group or demographic. (Not just kids, in other words.)

“It becomes this really pure art form,” Gill says, explaining that comics, with their unique blend of words and visuals, have a way of reaching readers that other media might not. “It teaches you things because it talks to you on this subconscious level,” he says.

That’s certainly been Gill’s experience with the reaction to “Strange Fruit.”

“That’s pretty much how people have viewed it, that these are very important stories about Black history, about American history,” he says. “Especially right now, where we’re in the process of talking about how history is being whitewashed again.”

Gill sat down recently to discuss how he curated the exhibit, what visitors have been learning from it, and why comics continue to inform, delight, and — in some cases — even scare people into wanting them banned.

Responses have been edited for length and clarity.

Well, the history of comics in America has been that they have been sanitized for kids. I remember once when I was teaching at a different school, I had a professor come out — he was a professor in painting, and I was drawing on my Cintiq [drawing tablet] at the time. And he goes, “Are those your little cartoons you’re drawing?” He, like, waves his hand, this little dismissive thing … I think people have this tendency to do that little hand wave, [but it’s actually] a very sophisticated medium, which relies on some very complicated things that people don’t really apply to it automatically.

I do a workshop called “Semiotics Storytelling and the Language of Comics,” where I talk about how semiotics [the study of signs and symbols] is the underpinning for comics, and it’s a very complicated thing about signs and symbols and meanings, and how we interpret meanings. Comics does this thing that other mediums don’t, which is, it communicates on this instinctive level to people. So I always say it’s like a sneaky way of teaching people things.

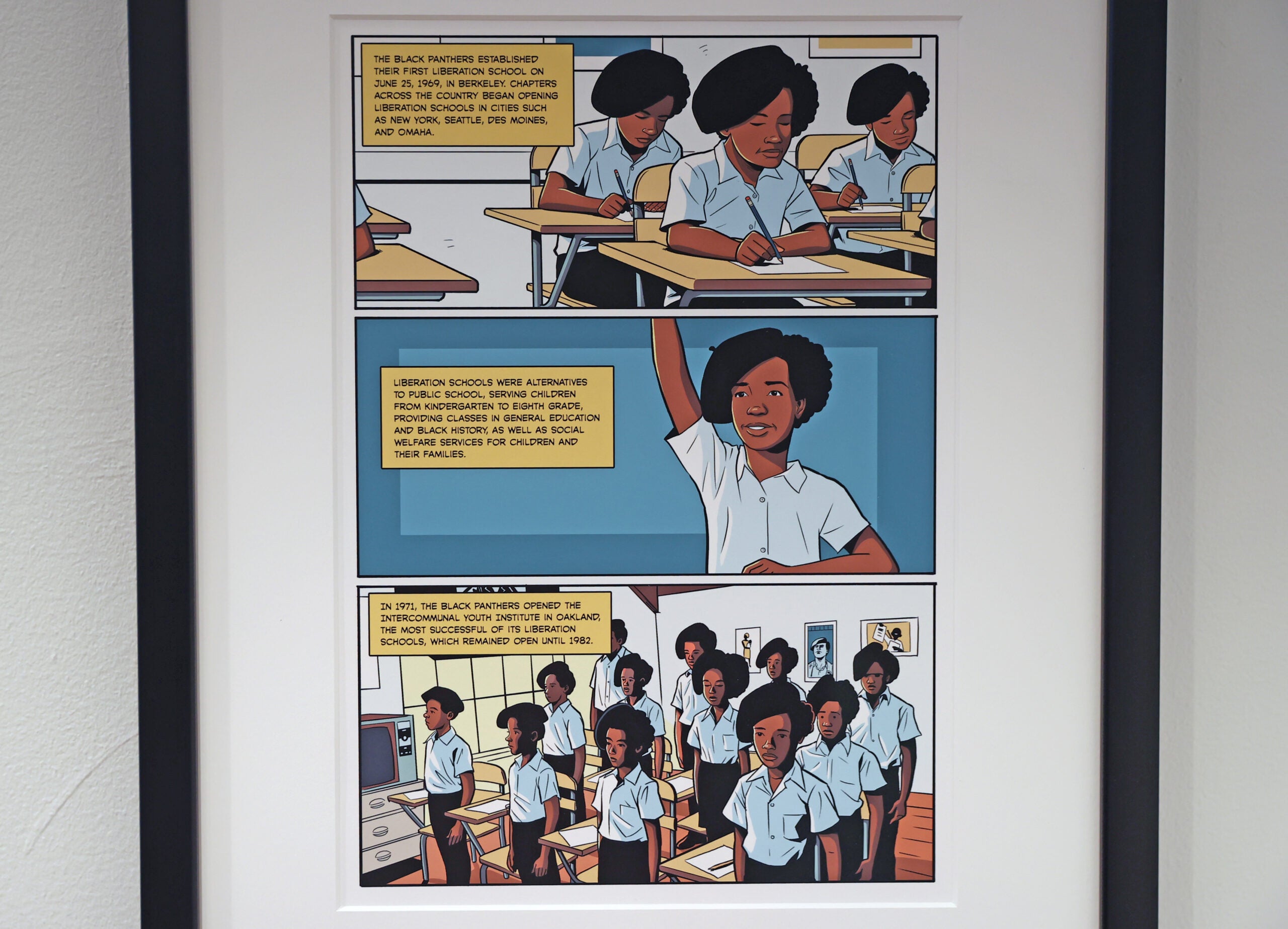

That being the case, comics don’t necessarily teach you one thing. They can teach you multiple different things … It makes it a really good medium for telling any kind of stories, whether it’s non-fiction stories about civil rights icons, or a Black girl gets in a spaceship and goes on an adventure. Those stories are all comics, and none of those define what comics are. And so the show really was about trying to give people an understanding that comics are more than the sum of its parts.

We probably have about 150 years represented in the show, from the early parts of comics history, including Winsor McCay [“Little Nemo”], George Herriman [“Krazy Kat”] … I wanted to put some history behind it, so I started to break it down into sections because inclusivity was really important to me. Because, you know, all types of people make comics, including George Herriman, who most people don’t know was Creole, which would have been considered Black at the time, but he hid who he was by telling people he was Greek in the early part of the 20th century.

So I broke it down into BIPOC cartoonists, queer cartoonists, women cartoonists, mainstream, nonfiction, and alternative press, because those encompass a lot of different types of people. And from there I started with the idea of mainstream, and for that I was thinking more history — superhero comics, newspaper strips, the sort of things that people typically think about. And then from there I branched off.

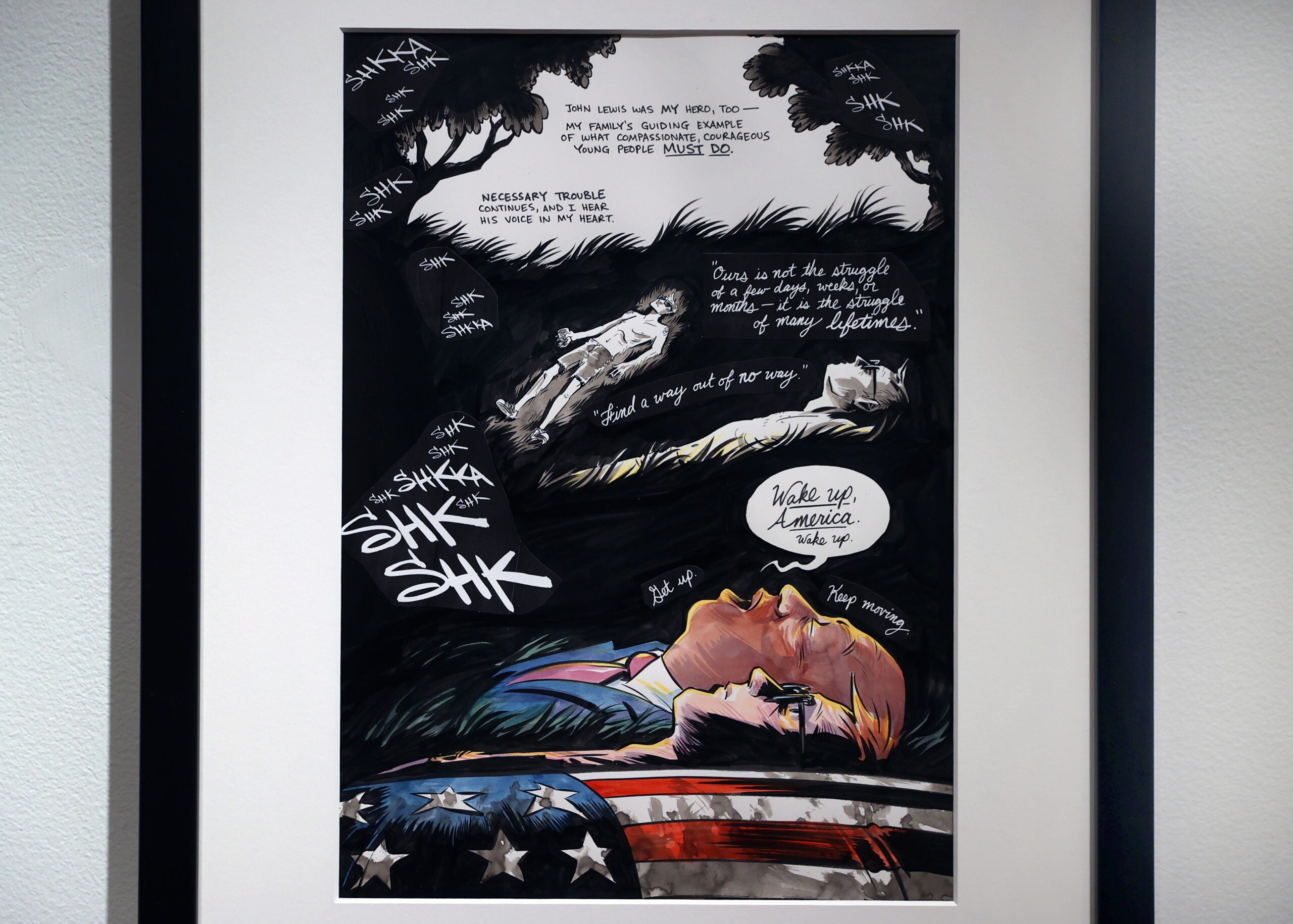

And so I did things like, I texted Nate Powell [illustrator of “March,” the graphic memoir of civil rights activist John Lewis], and I said, “Would you be willing to put some stuff in the show? I’d like to have something from ‘March.’ But if you want to send something else I’m happy to take that.” And he sent two pages from “March” and a page from “Save It For Later,” which are really great pages. And with [comic book artist] Stephen Bissette, I said “I’d love to have some ‘Swamp Thing’ stuff from you,” and we met like halfway between my house and his — I live in New Hampshire, he lives in Vermont — we met at The Weathervane [in Kittery], and we ate lobster, and we talked about it, and he brought me some pages.

We’ve got one of the original “Peanuts” strips … We were supposed to get the first appearance of Charlie Brown, and we got like maybe the third strip — I think it’s like the second or third strip, but it’s really early. I don’t care, it’s still brilliant. It’s really big — most people don’t realize that it’s probably like 6 by 6 or 7 inches, each individual panel, and the way in which he draws, like, the outline of a face: It’s just like a hump for the forehead, a little button nose, a little curve for the mouth, and it’s like all one brushstroke! It’s just incredible. So I got really obsessed about it for a while — I was looking at my old “Peanuts” comics.

The really interesting thing about “Peanuts,” I think I was probably a late adolescent before I actually considered that Charlie Brown was white. Mostly because of the way in which Schultz draws him. He’s really close to a smiley face, and that smiley face is so universal that you could pour yourself into it. I say comics are the ultimate empathy machine, and “Peanuts” is perfect for that.

It depends. Some people are like, “Oh, I remember this,” and then some people are like, “I had no idea that comics were banned in the 1950s, and that we had Congressional hearings.” We’ve got one of the books, one of the stories that actually caused the banning, which was “The Orphan” by Jack Kamen.

One of the highlights that I like to talk about is the process of comics being sanitized in the 1950s, and the Congressional hearings about it, which are really bananas. You can go and look on YouTube — there are some really crazy videos of this senator talking about the dangers of letting your kids read comics. And then he shows these kids, and they’re reading comics in the woods. And then, a kid rolls the comic up, puts it in his back pocket, pulls out a knife, and starts stabbing a tree!

Yeah! So sometimes people have a real clear sense. But sometimes people are just surprised, mostly because that history is kind of hidden.

You know, I know Maia Kobabe, and he is an incredibly wholesome individual [laughs], so it’s like, I don’t even understand it … Honestly, [between] some conservative politicians and Maia Kobabe, Maia Kobabe is the one I would leave with my children. [laughs]

I think it’s because [comics] are empathy machines. The thing that I think scares people in power, people who really rely on the othering of other peoples, is, what happens when we get unified? Right? There’s that hokey image, you know, like there’s Black power on one side, and white power on the other side, but the thing that really scares them is a Black hand and a white hand shaking hands. Well, that’s really hokey and kind of stupid, [but] there’s some truth in that.

At every point in American history, when those things start to become closer — from the first one, Nathaniel Bacon’s rebellion: When Nathaniel Bacon unifies the Black enslaved Africans and the white indentured servants against the planter class, it scares the crap out of them, right? So they actually have to go hard in the opposite direction. Happens in North Carolina after the Civil War with the Fusion Party, where you had these Black Republicans and these white, poor Democrats who started to come together and form this Fusion Party, which is this government against the planter class. [From that] we get the only known coup in American history where they take over Wilmington, North Carolina. So it scares them, right?

And because comics are this empathy machine, it’s a vehicle for telling stories that you don’t have to spend a lot of time giving words to. People can see images, and it can feel more real. Something that the American Library Association said is that a book is a movie you can see in your head. A comic is a movie that takes place while you’re ingesting it, at the same time. So you’re getting multiple modes of visual and written images that are coming in. So it just does something different to your mind.

I know there’s lots of academic papers about the idea of how comics communicate. But I think ultimately it’s about that empathy. You know, those simplistic characters that you can pour yourself into — like a Charlie Brown. And because of the way they’re drawn, we can see ourselves in it.

“Comics Is A Medium, Not A Genre” runs through March 24 at the Stone Gallery, Boston University Art Galleries, 855 Commonwealth Ave., inside the College of Fine Arts. Gallery hours are Tuesday-Saturday from 11 a.m.-5 p.m. Admission is free. For more information, visit bu.edu/art.

To hear the full interview with Joel Christian Gill, including discussion about his own work, his drawing methods, and the recurring “moral panic” surrounding comics and other art forms, download or listen to the latest episode of “Strip Search: The Comic Strip Podcast,” below:

The best events in the city, delivered to your inbox

Be civil. Be kind.

Read our full community guidelines.