The beginning of the end of the 22-year Amphenol/Franklin Power Products clean-up process could kick off this summer.

The 11o-page Final Decision document outlining the decades-long history of the site and the process to clean it up once and for all was released by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, late last week.

With the expectation that work will get started this summer, Mayor Steve Barnett is happy an end to this process is in sight, but knows it is far from over.

“We’re going to keep our continued pressure on the EPA, as long as it takes,” Barnett said. “We know that we are seeing the light at the end of the tunnel. And I want to make sure that we get all the way to the end of that tunnel.”

The statement of basis for the final clean-up plan was uploaded online in May 2022 and was discussed at a public meeting held on June 9, 2022. During the meeting, a few dozen residents and officials asked EPA officials questions about the plan. Answers to the questions posed during the public comment period are included in the Final Decision document.

Site history

The contamination accumulated over 22 years, when Bendix operated at the site, 400 N. Forsythe St., from 1961 to 1983. During that period, chemicals from plating operations at the site were routed into a sanitary sewer manhole and discharged into the municipal sanitary sewer system. In addition, spills on-site migrated to the soil beneath the building through cracks in the foundation.

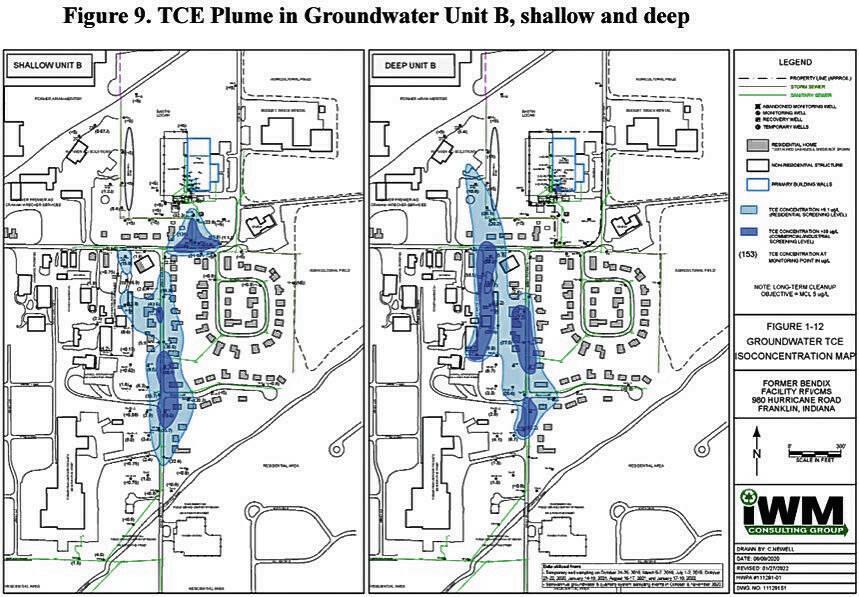

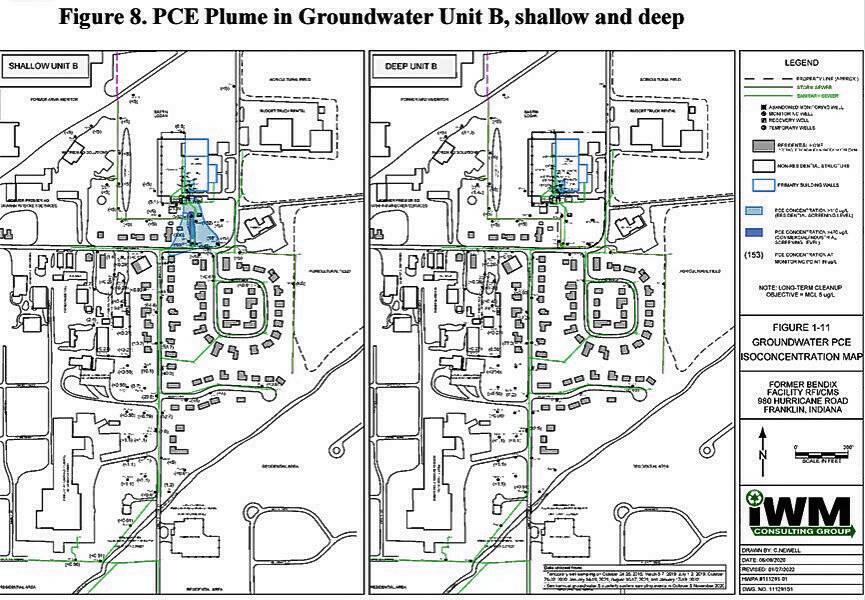

This caused volatile organic compounds, or VOC, including trichloroethylene, or TCE, and tetrachloroethylene, or PCE, to seep into the soil and groundwater. These chemicals are known carcinogens. Though children who grew up surrounding the site have been diagnosed with cancer, the state health department says there is not evidence to support a cancer cluster.

The contamination was first known to be an issue in 1984, after Bendix was purchased by Amphenol/Franklin Power Products, however no action was taken to clean it up at the time. Three cleanup orders have been initiated at the site since 1990, with the first resulting in a pump and treat system that is still in place at the site but will be decommissioned as part of the final clean-up plan.

The most recent order was issued in 2018, after it was revealed there could be additional contamination that was not cleaned up in the previous orders. At the time, people began to speak up about pediatric cancer, which fueled the efforts to ensure the site is fully remediated.

The order has resulted in further investigation at the site and extensive testing of groundwater and air at the site and within the plume of contamination, or area that the EPA believes the contamination has spread based on testing.

Vapor mitigation systems were installed in homes that tested over screening levels, sanitary sewers that were impacted by the contamination were replaced or relined to seal out contaminants, sewer laterals and/or plumbing systems were also replaced in impacted homes.

Contamination of the area should no longer be a concern because remaining contamination is deep below the ground, Barnett said Tuesday. Risk to area residents has been mitigated for several years, he said.

Barnett, other city officials and the city’s consultant Enviroforensics have been working with the EPA nonstop for the last five years to make sure the site is cleaned up appropriately. As the clean-up enters its next phase, that won’t change, he said.

“To me, that (cleaning up the site) means more than all the pretty stuff that we’ve actually seen going up,” Barnett said. “This is actually doing something that matters as people’s lives and their health, so I feel good about that.”

The solution

The EPA’s final remediation plan includes several methods to clean up the site and long-term monitoring.

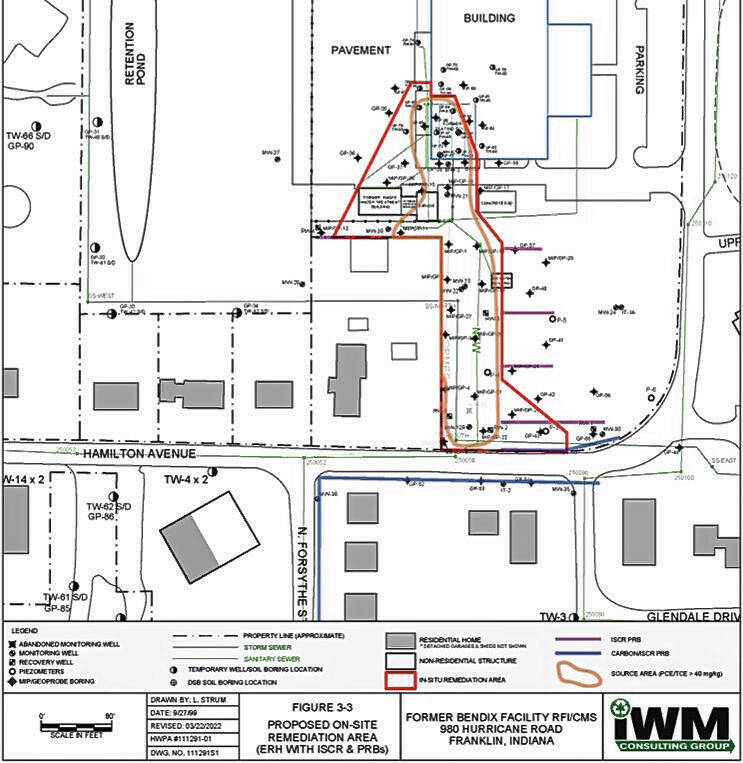

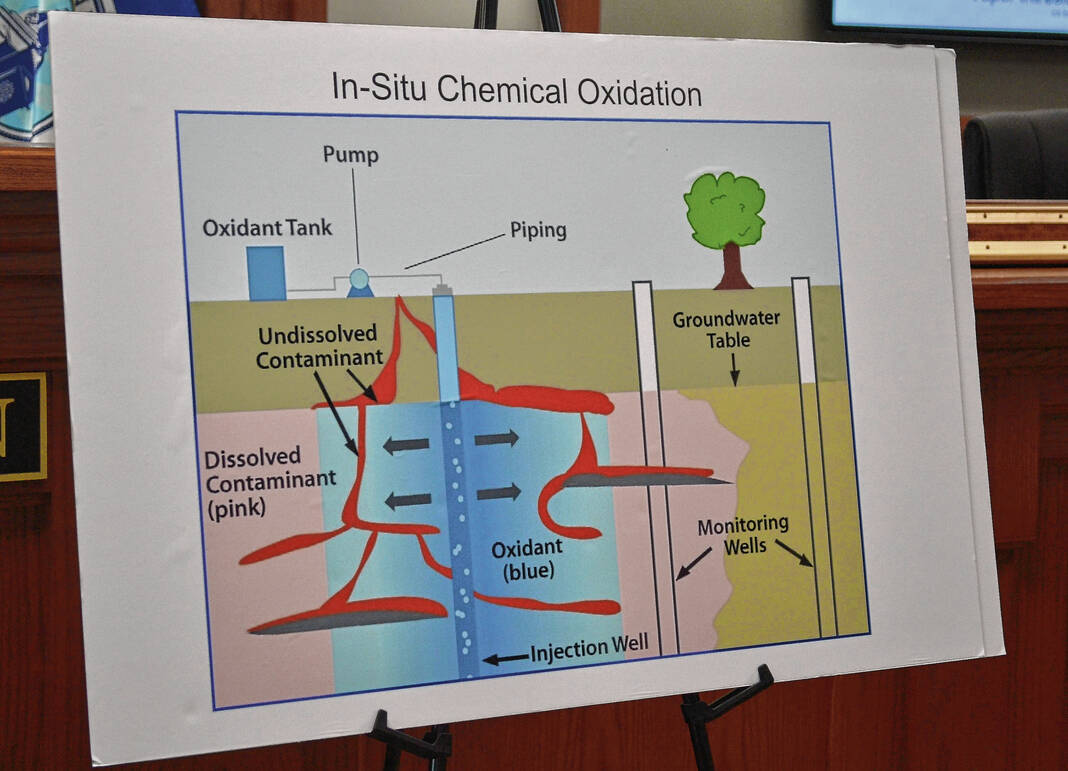

In a phased approach, technologies such as In-Situ Chemical Oxidation, or ISCO, and In-Situ Chemical Reduction, or ISCR, will be used in concert with Permeable Reactive Barriers, or PRB, and/or bioremediation. In layman’s terms these processes are designed to inject reactive chemicals into the ground to break down the contaminants. It is expected that the processes will take two to three years to eliminate TCE and PCE from the contamination area, Chris Black, the EPA’s corrective action project manager for the site, said during the June 9 public meeting.

The EPA would also monitor both processes to ensure groundwater cleanup goals are reached. Monitoring would take place over the next five to 10 years, until the EPA is confident the area is fully remediated, Black said in June.

“It is not a leave-it-alone remedy. We are going to monitor this over time and we are going to do a statistical method that determines if it is going to meet this goal in a specific amount of time. If it doesn’t we will try another remedy,” Black said. “It is part of a long-term remedy plan – we are not walking away.”

In the short term, these goals will help the EPA get the levels below levels that make vapor intrusion possible. In the long-term, the goal is to eliminate the contamination and to make groundwater in the plume safe to drink again, Black said in June.

However, Black noted, the groundwater is not used in any homes in the city. The city’s water is safe to drink, as Franklin residents get water from Indiana American Water, which pipes water to the city from a water source in Shelby County.

The processes that the EPA plans to use have been piloted in a smaller area of the site and have proven successful, so far, Black said in June.

The city’s consultant, Casey McFall with Enviroforensics, believes the EPA’s plan will appropriately mitigate remaining contamination both at the Amphenol site and in the plume south of the site.

“It is a solid approach to clean up what’s there,” he said Tuesday.

Final clean-up

The expectation is that the final cleanup will kick off sometime this summer and Barnett said he will advocate to keep that timeline.

The process to carry out ICSO and ISCR will involve a machine pressing steel rods into the ground at an appropriate depth to reach the contamination, then injecting carbon-based material into the ground to counteract the contamination, McFall explained. A permeable barrier will also be inserted into the ground to catch contaminants while allowing groundwater to move freely, he said.

The injected material and permeable barrier are made of propriety substances that is essentially food for bacteria that is already in the ground. They’re designed to promote that bacteria’s growth, which will help reduce the contamination over time, McFall said.

During the initial stage when the reactive chemicals are injected into the ground, there will be construction noise. However, the equipment will be removed and the chemicals will work over time to break down the contamination, while the EPA and the city monitor the progress over the course of up to 10 years.

“You inject it in the ground and let it work, but you have to monitor,” McFall said. “So, there’ll be groundwater monitoring wells already around there. And they’ll be monitoring those to see the effectiveness of putting the barrier in. What should happen is the concentration of contaminant in those groundwater wells should drop.”

During the final cleanup, McFall will watch on behalf of the city and help officials make sure the site is fully remediated.

“Once this gets going, I’ll go out and I’ll observe the initial kickoff and just to make sure everything’s going appropriately, but more than that, it’s just ensuring that things keep progressing,” McFall said. “I think the city’s done a good job working with the EPA to get this done as expeditiously as possible and we just want to make sure that that momentum continues.”

Seeing this process through is Barnett’s goal and keeping the clean-up on track is one of his proudest achievements as mayor.

“I can assure you that my administration is going to continue on down this path until we have turned over every single rock that can be turned over and make this whole and get this done,” Barnett said.

For more information visit epa.gov/in/amphenolfranklin-power-products-franklin-ind.