A Potential Triumph in Physics, Dogged by Accusation and Doubt

When University of Rochester physicist Ranga Dias announced this month that his lab had discovered a room-temperature superconductor — a feat that scientists have been chasing for decades — he drew excitement from some of his fellow physicists, but skepticism from others.

Superconductors, materials through which electricity flows without resistance, have been touted for their potential to unlock transformative new technologies, including the widespread adoption of energy efficient magnetic levitation trains and electricity grids and batteries that never lose power. But the materials usually acquire their superconductivity only below a critical temperature, typically close to absolute zero, or -273 degrees Celsius.

Within the past decade, scientists have discovered a class of materials that, at extreme pressures, show superconductivity at temperatures just a few tens of degrees below freezing, but the goal of a room-temperature superconductor has remained out of reach. In a paper published in the journal Nature on March 8, Dias and his colleagues reported they’d found a material, known as a lutetium hydride, that under high pressures can be superconducting at temperatures as high as 21 degrees Celsius, or nearly 70 degrees Fahrenheit — a discovery that many physicists describe as worthy of a Nobel Prize, if true.

In this demonstration, a magnet (gold) levitates over a traditional superconductor (black) that is cooled below its critical temperature by liquid nitrogen. If a material were to display superconducting properties at room temperature, it could unlock transformative new technologies.

Visual: Penn State Chemistry/YouTube

But the physics community has been here with Dias before. In 2020, a similarly bold claim from Dias — of a material that became superconducting at around 15 degrees Celsius (59 Fahrenheit) — unleashed a torrent of critiques and accusations, ultimately leading to the paper’s retraction last fall. Dias’ fiercest critics say that he has committed research misconduct, possibly on more than one occasion, and that he has yet to be held fully accountable. They also argue that his newest paper does little to address the serious technical questions that have been raised about his work. If anything, they suggest, it might raise new questions.

It “is like winning the lottery to discover a room-temperature superconductor, and they’re claiming to have done it multiple times,” said University of Florida physicist James Hamlin. “It just does not make sense.”

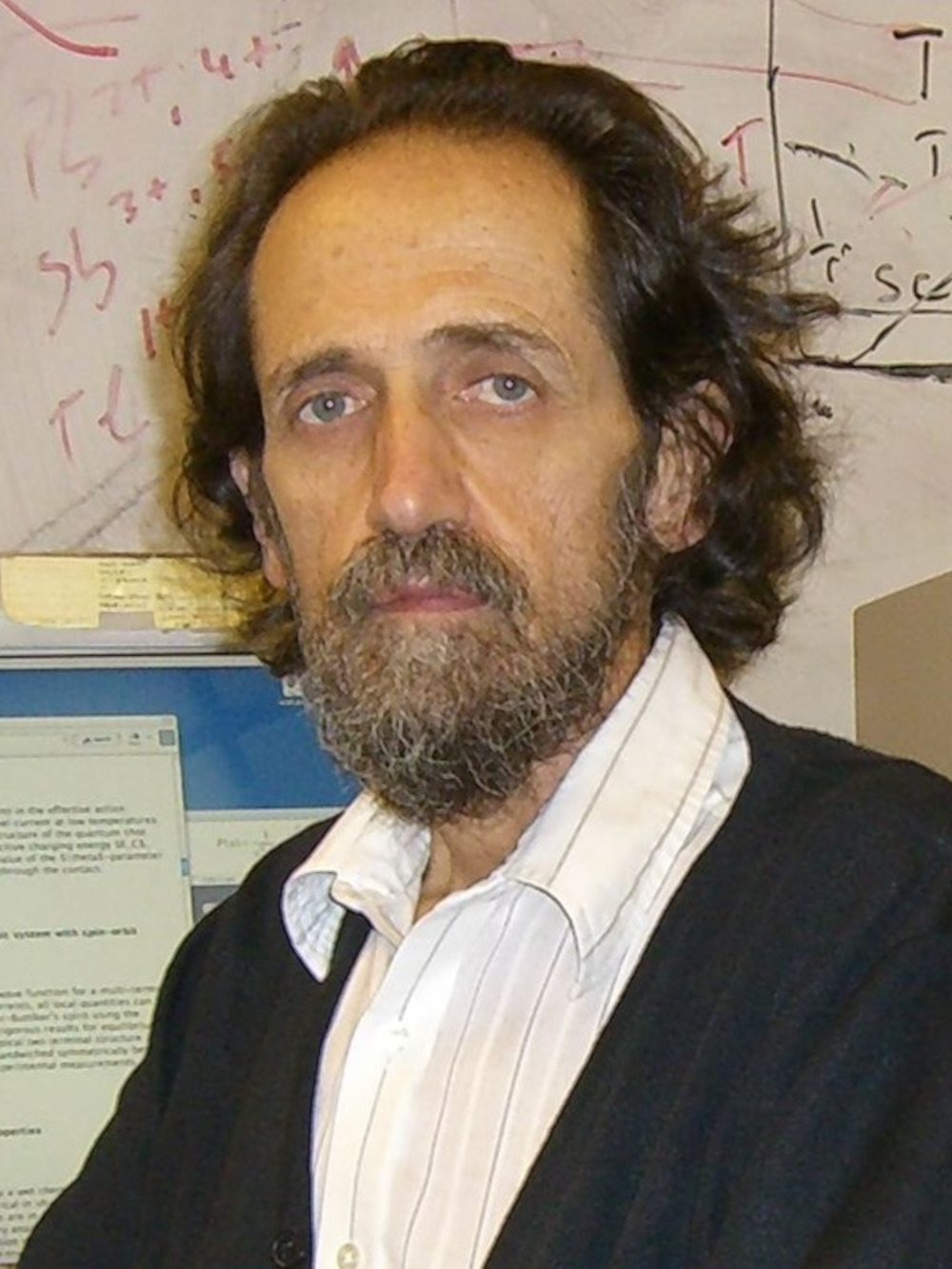

Jorge E. Hirsch, a professor of physics at the University of California, San Diego, who has been a staunch critic of Dias’ work, describes the controversy as having sown deep divisions in a burgeoning physics subfield. “There’s a lot of damage done because some people do believe it,” he said. “Students and postdocs and people don’t know what to believe.”

The first superconductor was discovered more than a century ago, by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who saw the property arise in mercury when it was cooled below -269 degrees Celsius. Since then, physicists have sought materials with ever-higher critical temperatures. In 1987, J. Georg Bednorz and K. Alexander Müller won a Nobel Prize for discovering copper oxide ceramics with a critical temperature of -238 degrees Celsius. In 2015, a team led by Mikhail Eremets, of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, showed that materials called hydrides could be superconducting at temperatures of -70 degrees Celsius when compressed in a diamond anvil cell, a molecular vice that squeezes tiny quantities of matter between two diamonds, crushing them to pressures around half that of the Earth’s core.

The discovery set off a rush to find other hydrides with even higher critical temperatures. It was during that rush that Dias, in 2020, reported in Nature that his team had discovered a carbon- and sulfur-rich hydride that could be superconducting at 15 degrees Celsius, about 5 degrees Celsius shy of standard definitions of room temperature. The paper catapulted Dias to a strata of fame rarely afforded to scientists. In 2021, he was named to Time magazine’s “100 Next,” a list of emerging leaders that also included singer Olivia Rodrigo, basketball star Luka Doncic, and then-future U.K. prime minister Rishi Sunak.

Where the public saw a rising star, however, Hirsch saw a series of red flags: suspiciously smooth data plots, opaque descriptions of experimental measurements, unexplained data analysis. “I saw it the first day,” Hirsch recalls of the 2020 Nature paper, “and when I saw it, I immediately said there’s something wrong with it — many things wrong with it.”

Hirsch has a reputation as an agitator who can be vigorous — and controversial — in his opinions. He’s best known for coming up with the h-index, a measure of research impact designed to shake up the very way scientists think of their peers. (The “h” is for Hirsch.) In 2006, he published a list of 15 reasons he thought the U.S. was planning a nuclear war with Iran.

In the superconducting community, he is seen as a contrarian. A vocal critic of hydride superconductors, he argues that his own theoretical calculations suggest the materials are not capable of acting as superconductors at all, and that numerous experimental papers claiming superconductivity in hydrides all suffer from fundamental misinterpretations of the data. He’s questioned, for instance, the validity of Eremets’ early hydride experiments, which have since been replicated by other researchers and are not in doubt among the wider community.

Physicist Jorge Hirsch is a staunch critic of hydride superconductors and Dias’ work. “Students and postdocs and people don’t know what to believe,” Hirsch says of the controversy.

Visual: Courtesy Jorge Hirsch

Peter Hirschfeld, a theorist at the University of Florida, says that sometimes Hirsch’s critiques have pushed too far. Asked if he felt Hirsch was the proverbial boy who cried wolf, Hirschfeld recognized the analogy “in the sense that sometimes the wolves have been there, and other times they haven’t.”

In Dias’ 2020 paper, Hirsch was sure he saw wolves — a pack of them. He’d found it curious that the paper had not been preceded by a preprint, as is common for high-profile physics papers. Also, data in the paper seemed to defy intuition.

One key plot showed how the new material’s electrical resistance changed as its temperature dropped: As a superconductor cools below its critical temperature, its electrical resistance falls to zero, signaling the transition to the superconducting state. In superconductors like the one Dias and his colleagues claimed to have found, the transition typically occurs gradually, over a span of a few degrees Celsius. When the material is placed in a strong magnetic field, the transition broadens even more.

To Hirsch, however, the transition region in Dias’ experiments seemed impossibly narrow, and it remained narrow even when a magnetic field was applied. Within a week, he and a colleague, Frank Marsiglio of the University of Alberta, Canada, co-authored a letter to Nature — published the following year — that expressed their misgivings. Hirsch would go on to call for Dias to release the raw data from the experiment. Dias and company rebuffed that request for more than a year, arguing that it would undercut patents the team had pending.

Meanwhile, additional doubts about the paper piled up. Other research groups, including Eremets’ team, were unable to replicate Dias’ findings. And it surfaced that one of Dias’ co-authors, Mathew Debessai, was a co-author on a previous study that was retracted over improperly manipulated experimental data. (Dias was not part of that previous study.)

In November 2021, Dias relented and published the group’s data. If the release was supposed to end the argument, it would only have the opposite effect.

In Dias’ 2020 Nature paper, the plot showing the temperature dependence of magnetic susceptibility — which is related to a material’s electrical resistance — looks more or less like a smooth curve, with a slight bit of random noise in the data. But when Hirsch zoomed in closely, he noticed that interspersed in the curve were tiny, discrete jumps in the data — each almost exactly the same height. To Hirsch and Dirk van der Marel of the University of Geneva, who joined in the analysis, it was as if someone had taken a more gently sloping curve and manually shifted segments of it by fixed increments to recreate the drop off in magnetic susceptibility that occurs when a superconductor cools below its critical temperature. In a paper published on the preprint server arXiv, Hirsch and van der Marel presented a detailed analysis suggesting that the data had been manipulated. “It’s clearly falsified,” Hirsch told Undark in December. “There’s no question.”

“We have done an analysis,” he added in a later interview, “and we have proven that those data cannot have come from a measurement device. They came from doing a calculation.”

Physicist Dirk van der Marel of the University of Geneva has joined Hirsch in criticisms of Dias’ work.

Visual: Courtesy Dirk van der Marel

Hirsch’s accusations ignited a war of words that spilled over into scientific meetings and popular media. At one point, a critique Hirsch published on arXiv was removed by moderators for unprofessional language, and Hirsch was temporarily banned from posting on the site. Speaking to Science magazine, Dias reportedly called Hirsch a “troll.” (Dias now says he thinks he was misquoted: “What we’re trying to say is that, let’s discuss science, let’s keep it to the science.”)

Hirsch’s criticisms, which he states are scientific and not personal in nature, are complicated by the fact that he has long held contrarian views on superconductivity. In a paper published on arXiv, Dias and his main collaborator, Ashkan Salamat, say that their antagonists’ critiques “stem from a lack of scientific understanding” about the experimental technique. They maintain that the artifacts are the result of legitimate methods they used to process their data and subtract out the background noise that inevitably obscures part of the signal in a superconductivity measurement. “This procedure,” the duo wrote, “is either not understood or deliberately ignored by Hirsch and van der Marel.”

But even to physicists such as Eremets, who firmly believe hydrides can be superconductors, it’s not clear why any method of subtracting background noise would give rise to the pattern seen in Dias’ Nature paper, and detractors say Dias and their colleagues never adequately explained why theirs does. Last September, editors at Nature sided with the critics, retracting Dias’ paper over questions “raised regarding the manner in which the data in this paper have been processed and analysed.”

Dias and company’s newest paper, which reports superconductivity at higher temperatures and milder pressures than the 2020 paper, might be seen as vindication for the embattled physicist. But while some in the community have expressed cautious optimism about the work, which was vetted by Nature’s peer review process, others, in light of previous controversy, are withholding judgement until Dias releases more experimental details and the work can be independently replicated by other groups.

Until then, doubts about the new work are likely to swirl. Eremets said that the new paper, like its predecessor, does not include the “full recipe” that other groups would need to reproduce the study. Hirsch said he continues to have concerns about the viability of the data, though he added in an email that if the finding holds up, “it would be a discovery of monumental proportions worthy of a Nobel Prize.”

There are whispers within the physics community that, if Dias did commit research misconduct in his 2020 Nature paper, it may not have been his first such indiscretion. In November 2022, Hirsch received an anonymous tip suggesting that he compare Dias’ 2013 Ph.D. thesis with that of Hamlin, the University of Florida professor, who completed his Ph.D. in 2007. Using an online plagiarism tool called Compilatio, van der Marel said, they found a 15 percent similarity between the two documents. (I compared the two documents using the online software Copyleaks, and found that 2 percent of the passages in Dias’ document were verbatim identical to Hamlin’s, 2 percent had minor changes, and 2 percent were paraphrased.)

“Ranga copied significant portions of my dissertation without quoting my dissertation,” Hamlin said. By his count, Ranga used “something on the order of five to 10 pages of material, sprinkled throughout. Not in fragments of sentences, but in whole paragraphs.”

Other behavior from Dias has also raised eyebrows. The digital science magazine Quanta recently reported that, in a 2021 talk posted to YouTube, Dias told the Sri Lanka Association for the Advancement of Science that he’d raised $20 million for his startup company, Unearthly Metals. The video displayed a list of investors that included the CEOs of OpenAI and Spotify. After the Quanta story appeared, Dias’ team reportedly walked those claims back, telling Quanta that the statements were “aspirational,” that the money had not been raised, and that the names were only prospective investors. The YouTube video has since been removed.

In an interview with Undark, Dias unequivocally denied that he or any member of his team had committed research fraud. He avoided rebutting specific technical points levelled against his 2020 paper, but did address technical concerns about the 2023 study, stating the team would be happy to work with any experimentalists attempting to reproduce their work. “The evidence is there,” he said. “Either you can believe that evidence or not, but you can’t ignore it.” Dias did not respond to questions, sent through a public relations officer, about the allegations of plagiarism in his dissertation.

The University of Rochester has conducted three inquiries of Dias — two related to the 2020 Nature paper and another related to its retraction — and officials say that all three concluded that there was no evidence of scientific misconduct. The university did not provide details of the investigations, noting only “that Nature’s explanation regarding the retraction does not raise concerns of scientific misconduct.”

Dias has sent at least one of his critics, van der Marel, a series of cease-and-desist letters, demanding that van der Marel save all correspondence in case of legal action.

Some physicists say the controversy has cast a pall over the entire subfield of superconducting hydrides, seen by some as science’s best hope for achieving the sought-after goal of room-temperature superconductivity. “There’s a little renaissance going on, both in high-pressure experiments and the theoretical approach to materials discovery, superconductivity, superconductor discovery,” Hirschfeld said. “All those little renaissances are going on, but they’re both being held back or oppressed a little bit by the charges around ideas and skepticism in the community.” He added, “It’s definitely rubbed off on efforts to make and discover new materials.”

For Eremets, however, the heightened scrutiny of superconducting hydride experiments could prove to be a boon in the long run. Unlike Hirsch, he believes the evidence that hydrides can be superconducting remains incontrovertible, but he sees the controversy surrounding Dias’ work as a welcome reminder of the importance of independently verifying results. “We would compare that not with bumps on the road, but rather with stones or fallen branches,” he wrote in an email. “One should slow down or even leave a car to clean the road.”

UPDATE: An earlier version of the article credited a superconductor demonstration video to Portland State University. The video was made by Penn State.

Kit Chapman is a science writer and lecturer based in Falmouth, U.K.

Comments are automatically closed one year after article publication. Archived comments are below.

The video is not from Portland State University. It’s from Penn State.

Thanks for bringing this to our attention, Sylvia. We’ve corrected it.

Ambient temperature superconducting materials, when available would change the face of several technologies for societal benefits. Readers interested in learning about superconductivity and its applications should read my 2021 book: “Superconducting Materials and Their Applications: An Interdisciplinary Approach”, by J.V. Yakhmi, Pub: Inst. of Physics Publishing Ltd (UK), Published in Feb. 2021, 148 pages. Copyright © IOP Publishing Ltd 2021, • e-Book ISBN-13: 978-0-7503-2256 • Print ISBN 10: 0750322543. – Prof. Dr. J.V. Yakhmi