It’s tempting to think of purchasing plastic cups labeled as compostable or using plastic cutlery made of biodegradable materials as a better choice for the environment—but there are a lot of complexities at play. A study published Wednesday in PLOS ONE demonstrates how a popular bioplastic advertised as biodegradable does not actually break down in the ocean.

The world’s got a big plastic problem, and it’s choking our oceans. For every person on Earth, there are now 21,000 pieces of plastic in the ocean; these plastics last so long in the environment that they’re outside a framework of time that humans can understand. At first blush, the idea of plastic made out of natural materials like cornstarch, sugarcane, or other biomass that can harmlessly break down may seem like a genius solution. Enter bioplastics, which are made of renewable materials that are biodegradable. (Polluters love bioplastics, by the way: Coca-Cola, the biggest plastic polluter in the world, recently rolled out a bioplastic bottle it advertised as “100% plant-based.”)

But the terms compostable or biodegradable don’t mean that a plastic cup will dissolve peacefully in the ocean; when we’re talking about plastic items, those terms represent conditions that are not found in nature. Industrial composting, for example, is able to rigorously monitor pressure and temperature levels in compost that can’t be achieved in home composting setups to allow it to break down materials the home composter simply can’t achieve. The idea of something being “biodegradable” also doesn’t take into account the variety of settings a piece of trash might find itself in: something that can break down in a forest may fare much differently in the ocean.

“What consumers don’t know is that, for these objects to be compostable, they need to go into composting facilities,” Sarah-Jeanne Royer, an oceanographer and researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and lead author of the study, told Earther. “But the consumers, they will go, and they will get a cup, and they might put it in a normal bin.” Even if someone does use a compost bin, Boyer says, there’s always a chance that wind, a spill, or a poorly maintained bin could release trash into ecosystems, where it might find its way to the ocean.

There has been a lot of previous work around how different plastics break down in various settings, including some research on how it could break down in marine-like environments, but nearly all of those studies were done in lab-controlled conditions. This study represents one of the first to look at how these plastics, especially PLA, would fare in the actual ocean.

This study used samples of polylactic acid (PLA), a popular bioplastic, made into textiles—a particular interest of Royer’s, since fast fashion is one of the most polluting industries in the world, and clothes made of plastic like Spandex or polyester can shed harmful fibers into the water system through normal washing. However, she stressed that the PLA tested in this study is the same type of plastic shoppers may see in cutlery and other items advertised as “biodegradable,” “compostable,” or “green.”

“It doesn’t really matter if it’s for a single-use item or for a textile,” she said. “It’s the same chemical composition.”

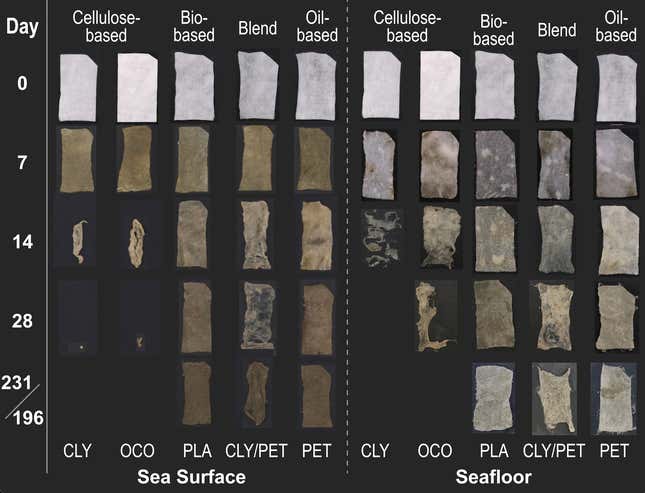

In order to test how PLA would fare in the ocean, Royer and her colleagues exposed samples of it to marine environments. As a control, they also included samples of cellulose-based fibers (like cotton), traditional oil-based fibers (like polyester and polypropylene), and fabrics that were a blend between the two; these samples were put into small cages. Some cages were left to float at the ocean’s surface, while others were sunk 10 meters deep for 14 months off a pier near the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in San Diego, California.

Some of the results were unsurprising. Lab testing confirmed that the natural-based materials had begun to biologically break down, not just shed from wear and tear, while the oil-based plastics did not degrade. But the bio-based plastic samples—the ones advertised as biodegradable—also showed no signs of breaking down.

The obvious answer would be to increase access to composting facilities for these items, but that’s much easier said than done. Just about 27% of Americans have access to industrial composting facilities. Some industrial composters have also stopped taking bioplastics altogether, saying they drive up operational costs.

Boyer is based in Hawaii, where she points out that there’s only one composting facility in the entire state, making it incredibly difficult to responsibly dispose of bioplastics before they end up in landfills or the ocean. In the long term, she said, the only solution that makes sense is curbing our addiction to single-use items.

Using bioplastics is “a bit of greenwashing to feel good,” Boyer said. “They think they are doing good, but they’re not really doing good.”