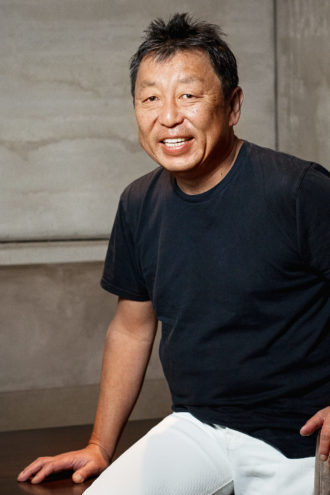

Wearing his signature outfit—white jeans, long-sleeve black shirt, white Converse—Teiichi Sakurai mounts a low platform in the back of Tei-An, his serene Arts District restaurant. Before him is a smooth wood work surface; behind him on a wall are mounted a half dozen chestnut rolling pins of varying lengths. The incremental gradations—the longest is 3 feet—allow him to roll buckwheat dough into a smooth sheet that he’ll fold again and again and then cut into bundles of square noodles that measure precisely 1.5 millimeters a side. The dough is light beige, like natural linen. The Japanese call the color uguisu, the name of a bush warbler that also makes appearances in haiku. The whole process is both intuition and ancient code. It takes years to master.

On any given night at Tei-An, you might find Toyota executives, a group that has driven up from Houston, or chef Thomas Keller, out from The French Laundry in California, sitting at the horseshoe-shaped bar or a secluded table, silently focused on a flight of uni. The slim 51-year-old, whom everyone calls Teach, commands the respect of his peers, who have seen him bring authentic Japanese food to Dallas and elevate it to something sublime. Every bite at Tei-An is not only the best bite of Japanese food you’ve ever had, but is also part of an integrated, artful experience that references 400 years of history.

At the center of it all is Sakurai. And at the center for Sakurai is soba.

Sakurai didn’t come to soba right away. he had to wait, letting it ripen in him. He remembers being stuck in Tokyo soba shops as a boy, tugging at his grandfather’s sleeve while the adults drank sake and talked for hours. I’m so bored, he would say. Sit down, came the instruction. Wait. And so he did, wondering what was so fascinating about this quiet, austere way of gathering, this adult world he knew nothing about.

Sakurai didn’t come to soba right away. he had to wait, letting it ripen in him. He remembers being stuck in Tokyo soba shops as a boy, tugging at his grandfather’s sleeve while the adults drank sake and talked for hours. I’m so bored, he would say. Sit down, came the instruction. Wait. And so he did, wondering what was so fascinating about this quiet, austere way of gathering, this adult world he knew nothing about.

Instead, the young boy was enamored with flight. Sakurai remembers standing as an 8-year-old with his father, seeing planes for the first time at an airport. The moment of takeoff fascinated him. “There were lots of people involved, scurrying around, getting it just right,” he says. “Then, after three minutes, the plane just goes away, disappears. There’s a big sound as the gigantic object takes off. And you think it cannot be happening.”

Drawn to the mechanisms and complexity of aerodynamics, he studied aviation in high school. After graduation, he enrolled in an aviation school in Tokyo that happened to have an exchange program with the United States. That’s how, in 1985, the 19-year-old came to Amarillo, Texas, to learn how to fly.

He was an absolute outsider, but what he remembers most is the genuineness of people in the Panhandle. He completed his training and got his pilot’s license. But the boy from Tokyo missed the big city. So he came to Dallas.

Sakurai’s first job was at the now-closed Royal Tokyo on Greenville, where he began working in 1989. It was all Rolls-Royces and Cadillacs rolling up at 5:30 pm, releasing big-haired ladies like goddesses from latter-day chariots. All restaurant menus were practically identical at the time, even Japanese ones, and had to include the ubiquitous steak, chicken, salad. But then, he says, people started traveling more. When they came back to Dallas, as though by some miracle, they were willing to try something different.

In the meantime, he had been pushing them, gently, expanding the limited sushi selection at Royal Tokyo from a few standards—salmon, shrimp, the ever-present tuna—to more than a dozen. It was a deliberate move, made with patience. “You have to think why you’re here,” he says. “You’re Japanese. You’re in Dallas. You have to introduce people.”

With the savvy of a businessman’s son, he opened his first restaurant, Teppo, in 1995. Sushi was by then established, but Teppo introduced yakitori, the Japanese tradition of chicken expertly grilled on skewers—the heart, liver, gizzard, thigh. Even though he only knew of one other place specializing in yakitori at the time, the former Kokekokko in Los Angeles, he chose not to lead with the familiar. His restaurant boldly bore the moniker “yakitori and sushi bar.”

Three years later, he opened Tei Tei Robata Bar, incorporating the style from the northern island of Hokkaido, the robata a brazier around which people gather to grill whole fish, whole vegetables, and tender fish collars. As far as he knew, his was the only robata-focused restaurant in the country. Later, when he opened Ten Ramen, his snug, counter-only, Tokyo-style ramen shop in Sylvan Thirty, he wasn’t sure Dallas would accept the stand-up-style eating and the heat that mimicked the bustling stands of Japan’s capital. But that was his mission, to show and share culture.

It’s at Tei-An, though, that he finally devoted himself to the world of the Japanese buckwheat noodle he’d glimpsed as a child with his grandfather. The slender beige noodle may seem a reversion to something simpler than dazzling sashimi cuts, but in the world of Japanese food, soba’s humble look is deceptive. It’s an exacting art, chosen by only a few. “Soba is the last thing to understand,” Sakurai says. “For Japanese people, too.”

A lot of things go into soba. You could say everything goes into soba.

The idea of soba came from monks. In many ways, it is the closest we get to shōjin ryōri, vegetarian Buddhist temple foods: roots, simple broths, tofu. Soba’s simple presentation—naked noodles served plain on a bamboo basket with dipping sauce—is a testament to the same subtle aesthetic that informed tea ceremony and the high art of kaiseki, Japan’s haute cuisine. It’s meditative, as much in the making as in the eating. The length of a strand of soba is the distance from the hand to the mouth.

The ni-hachi soba style of Tokyo is based on the words “two” and “eight” for the ratio of 80 percent buckwheat flour to 20 percent wheat flour, but also the 2 x 8 coins, the cost of soba in Edo-period Tokyo. This is the kind of obscure detail Sakurai knows. Talking with him, information rises to the surface gradually, in series of word images like haikus that wash over you in his soft-spoken, sometimes halting English. Sakurai steeps you gently in history. His own family’s roots reach back 400 years, and family photographs that are in his mother’s keeping in Tokyo bear the family’s ancient crest (kamon). All of this is in his blood.

The first soba shops in Japan arose during the Edo period, Japan’s renaissance from 1603 to 1868, when a culture of food and art flourished in Edo, the city that would become Tokyo. Soba shops were gathering places for eating, drinking, and literary discussions. From the table manner to the dipping of the noodles in sauce, “there’s a lot of Edo fashion to it, Edo spirit in it,” Sakurai says. For him, it’s nostalgic, though for a period he never knew.

It’s easy to see why the soba tradition appeals to him when he talks about another figure who inhabited the zone between art, spirituality, and craft, the 16th-century figure Rikyū, the first master of tea ceremony. “When he did tea ceremony, he chose one flower, the best flower, not thousands,” Sakurai says. Beauty in simplicity, beauty in reduction—these are precepts he admires. He has no use for the likes of the extravagant Imperial Regent Hideyoshi, with his gold-leaf ornamented tearoom, who asked that Rikyū perform seppuku, ritual suicide, over differences of philosophy that played out in the tearoom.

Subtlety. Lack of flashiness. This is why Sakurai likes the Converse tennis shoes he always wears, with their logo hidden on the bottom. That is the Tokyo way, he says. It’s in that hidden Edo that soba was refined. And, after the success of his first two restaurants, it was soba’s language that Sakurai longed to learn.

In 2006, Sakurai attended the Tsukiji Soba Academy in Tokyo to train in the art of soba-making, proceeding directly to the advanced class due to his skill. He learned how to handle ku-ichi soba (a 90 percent buckwheat, 10 percent wheat flour ratio) and even the impossibly fragile 100 percent buckwheat dough. “You have to experience a very sophisticated feeling in the fingers,” he says. “Like touching a baby.”

Making soba is nothing like Chinese noodle-pulling, all kinetic slap and tug. Nor is it like fashioning ramen, supple and willing with gluten. Soba is more sophisticated, more fragile, with barely any gluten to provide give. Tug on a slender, fresh noodle—and it breaks.

In his soba-making room at Tei-An, Sakurai demonstrates the steps, each with a name and each a separate challenge. Kasui: adding water slowly. “If you don’t do it at the right moment, it cracks,” he says. Kone: kneading the dough until it’s as smooth as an earlobe. Maru-dashi: forming a 45-degree pyramid. Then comes the flattening, also in stages. First into a disk, like an ancient sun, which he works clockwise; then a square. Here he switches rolling pins, wrapping the dough around it like a scroll and then unrolling it until it lengthens into a broad rectangle. Then noshi, the final flattening, until no unevenness remains, not a ripple.

The sieved flour he sprinkles before folding flecks the smooth expanse. The rectangular knife looks blunt, but cuts straight down in quick, regular movements, shearing off the noodles with their perfectly square cross sections. Edges are important in the mouth, an integral part of Japanese food culture, as much with soba as with sashimi. Sakurai moves with the knife, sliding back the board that holds the stack in place. He moves swiftly, rhythmically. Finally, he shakes off the flour from the skeins, which glide over his fingers, looking fragile as hair. He gently lays them in a walnut wood box called a fune, meaning ship.

Dallas is a little too dry for soba, especially in the winter, when Sakurai adds more water to the dough to prevent the cracking that is the fragile noodle’s primary pitfall. You have a feeling when this is going to happen, he says, but he always continues. To see. To study. An endless apprenticeship that acknowledges the patterns of weather. “Soba is like meditation. It’s like Zen. It reflects your state of mind,” he says. “We have to be pure-minded, more than with anything else you cook.”

On a late morning, Bruno Davaillon walks into Tei-An with a parcel of delicate green tea pastries from a Japanese bakery in Paris, from which he’s just returned. He and Sakurai met at a charity event at The Mansion on Turtle Creek, where the Frenchman was chef, and they formed a fast friendship, united in their expatriate status and their understated temperaments. Several years ago, they traveled together to Tokyo, reveling in the exquisite refinement of craft, the work of a soba master who has made soba for 40 years.

Davaillon says he admires Sakurai’s dedication. “He’s someone who works incredibly hard. He does things all the way,” Davaillon says. “It reminds me of the French restaurants where the chef’s name is on the door.” He says that to see Sakurai’s work is to experience an aesthetic that would fit in one of the most high-end restaurants in Tokyo.

Sakurai met his wife, Takako, who is from Mie prefecture in Japan, through his travels. Though she was in Dallas at the time, working for the travel agency that booked his flights for many years: Miami, Las Vegas, New York, Paris, London. They had only interacted over the phone, the travel agent and the man who seemed to circumnavigate the world, until she showed up as a customer in his restaurant one day, almost two decades ago. “You know me,” she said. “I’m the one who is booking your flights.” He taught her to make sushi, and she now works alongside him in the restaurant, her pressed sushi station the last stop before his soba-making room.

Why Sakurai has stayed in Dallas is a mystery in many ways. Opening Tei-An was a labor of love that nearly did him in. It opened in August 2008 (an easily remembered anniversary, 8/8/08). Two months later, his father died in Tokyo. The eldest son, Sakurai was absent, and his father’s loss devastated him. He had followed his dream, but it was a cruel reminder that to render faithful homage to your country is not the same as being there.

The man of many interests could have done many things. His mother made pottery and practiced the arts of flower arranging (ikebana), tea ceremony, and kimono dressing (kitsuke)—all the Edo-period refinements but calligraphy. He himself taught pottery at SMU for a while, back when he had more time, when he wasn’t cooking as much but managing Teppo and Tei Tei Robata Bar—another detail that emerges with the casualness of an afterthought. His collection of Edo-period soba-choko dipping cups are tucked into a recess in Tei-An, almost 85 arranged on clear glass shelves. He has purchased them in Tokyo antique shops over 20 years, always the blue and white Ko-Imari style. Some of the larger ones have designs of dragons, one of the 12 sacred zodiac signs, for which artists had to receive authorization from the government, he says, or risk being killed.

If you get Sakurai talking about the pottery tradition in Japan, his homeland dotted by mountains with fiery kilns, he’ll point out the “sky” pattern in a bowl he loves, on which errant streaks of red, the result of sparks from embers, look like a sky at sunset. His favorites are the Bizen and Karatsu styles of pottery, dark and subdued.

A tire from a sports car, artfully filled with plants, fills a small table in front of us. The tread pattern is the epitome of regularity, meant to help the tire hug the road at 200 mph. The shallow bowl set inside to hold the plants is odd-shaped and imperfect. It’s a deliberate juxtaposition that’s important to him. “People’s hands or sadness or happiness affect the shape,” he says, quietly handing over the clay bowl.

With him, it’s always two things at once, a pushing and pulling in dynamic tension. Sharing and the desire to be alone. Cityscapes and countryside. Tranquility and the complexity of an engine.

“People usually take the easy way out, but that’s not really a good result,” Sakurai says. “You have to take responsibility. How many people can you involve in your passion? That’s a great feeling if you can do that.”

There is a word, kansha. It means appreciation. After you’ve done everything—traveled, started businesses, managed people, scurried in the model of the perfect harried businessman—you have a deep kind of “huh” feeling. Life experiences start connecting. You start to have feelings about soba. At least this was true for him. Perhaps this is when you realize that a soba shop is a sanctuary, a balm in a busy city. “There’s no loud noise in a soba place in Japan,” Sakurai says. “It’s serene, almost like a soft landing place.”

If he has his way, he will eventually retire to a house on the Izu Peninsula, south of Tokyo, famed for its natural beauty—away from the big city. “Anything connected to nature I respect,” he says. Sometimes, even now, he retreats. “Every once in a while, people are loud, there’s too much noise,” he says of his restaurant. At those times, he melts away from the busy dining room in his cool, inconspicuous, soft-spoken way.

Making Soba

1. Sakurai starts with an 80-20 mix of California buckwheat and wheat flours, and then adds water slowly, a process known as kasui, to prevent the dough from cracking. Then he kneads the dough until it’s as smooth as an earlobe and forms it into a 45-degree pyramid.

2. Next comes the flattening: first into a disk, which Sakurai works clockwise; then a square. At this point he changes rolling pins, wrapping the dough around the larger pin like a scroll and then unrolling it until it lengthens into a broad rectangle.

3. Sakurai uses a rectangular knife to expertly cut the dough into square-edged sections.

4. After shaking off any excess flour, he gently lays the skeins in a walnut wood box called a fune, meaning ship.