How Africa’s Premier Gravel-Racing Team Is Moving Forward After the Death of Their Founder

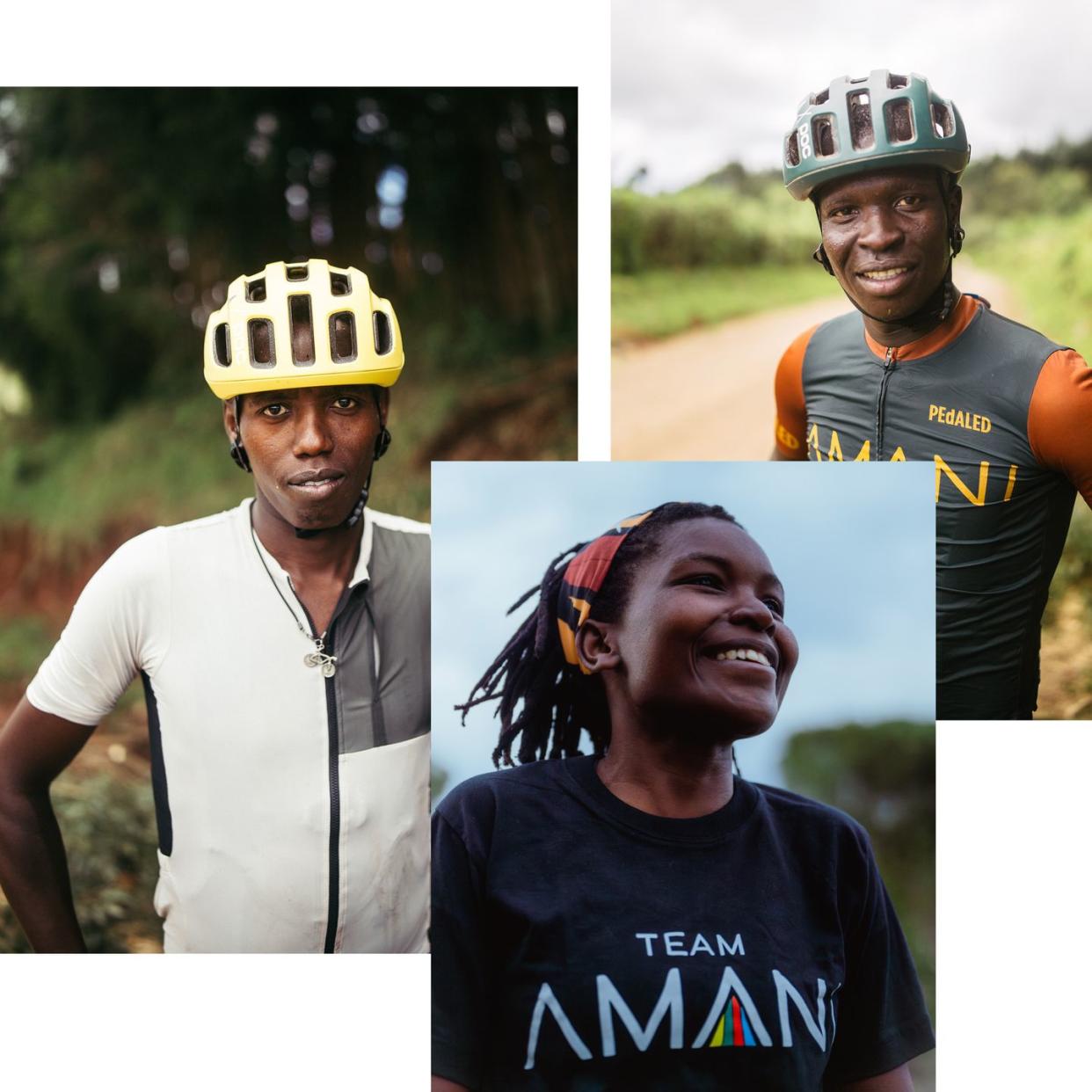

This weekend, for the first time ever, a trio of African pros will line up for gravel’s most prestigious, most intensely fought race. Unbound Gravel takes riders through the Flint Hills of eastern Kansas, along winding prairie roads littered with sharp rocks and steep climbs. Kenya-based Team Amani has sent John Kariuki, a 26-year-old Kenyan, along with two Ugandan teammates, Charles Kagimu, 24, and Jordan Schleck, 20, to face off against the world’s top gravel racers on the 200-mile course.

There will be a gaping hole in the Amani lineup, though. The team’s founder and captain, Sule Kangangi, will not be in Kansas.

Sule was a visionary and a leader in African cycling. He’d had an inauspicious early childhood; neither of his parents were a meaningful presence in his life after age 11. He essentially raised himself. His sister went to live with their grandparents while he stayed behind in Kapsuswa, a poor neighborhood on the outskirts of Eldoret. He was old enough to find work, the thinking went, old enough to contribute financially to the family.

Join Bicycling for unlimited access to best-in-class storytelling, exhaustive gear reviews, and expert training advice that will make you a better cyclist.

So Sule sold secondhand clothes. He swept the veranda at a local shop. He herded cattle. School wasn’t an option—he couldn’t afford the tuition—and Kapsuswa was in the process of being demolished on account of crime, which forced Sule to couch surf, moving from the home of one alcoholic uncle to another. Sometimes he had a mattress; sometimes his mattress got stolen.

Every few days, Sule would visit his grandparents. His grandfather had been a janitor; the steady work had granted him financial security. He was old by the time Sule was a teen and would get around slowly on a black upright singlespeed bicycle—a Black Mamba, as such workhorses are called in East Africa. From his grandfather, Sule got a sense of what a happy, stable life looked like, and he wanted to create something similar for himself. He worked in a print shop and a convenience store. He took his grandfather’s bike and put a seat on the back, to transport paying customers around Eldoret.

Then in 2007, Sule pieced together a road bike. He stepped up his training until he was often doing 150-mile rides, and he started to race. In 2016, a pro team, Kenyan Riders, recruited him. He raced in China, the United Arab Emirates, and Australia. He taught himself English, zeroing in on one new word a day: “exertion,” for example, and “exhaustion.”

Meanwhile, as Sule married and started a family, he tried to grow bike culture in East Africa. He coordinated a Black Mamba racing series. He pushed to attain better prize money for African riders at races—and grew leery of elite road racing, in which riders climb the ranks via an arcane points system that awards them for competing in races that are almost invariably held in Europe. When he launched Team Amani in 2018, his goal was to empower East African cyclists, both male and female, as they vie for dominance in gravel and mountain bike racing.

In August 2022, Sule traveled to the U.S. with Kariuki and Schleck, aiming to compete in three major stateside races—the Leadville 100, SBT GRVL, and finally the Vermont Overland, a roughly 59-mile ordeal that climbs about 7,500 feet through small towns and forests around Windsor, Vermont.

More than 1,100 riders lined up for the race on a cool, cloudless late-summer day. I was one of them, fighting to a 211th-place finish among men. In the beer line later, I found myself chatting with a fellow racer. Casually ignorant, I asked him how he did.

“I won the race,” he proclaimed.

It was John Kariuki. No Black rider had ever won a major American gravel race, and Kariuki’s teammate Jordan Schleck had sweetened the moment by finishing third.

But Sule never made it to the finish line. Two hours into the race, Kevin Bouchard-Hall, a physical therapist riding just behind him, found him lying beside a tree in a fetal position with blood coming from his mouth. “The fork on his bike had snapped off,” says Bouchard-Hall.

Bouchard-Hall suspects that Sule hit the tree, but no one will ever know precisely what happened. Sule died on the way to the hospital. He was 33 years old. His teammates, who had gotten news of the crash and assumed it meant a fracture at worst, were stunned. “We were crying,” Schleck says. “We couldn’t seriously believe this had happened.”

Suddenly Sule’s three young children had no father, his wife became a widow, and his dream of launching East Africa as a power in gravel racing was shrouded in question marks.

“More coffee, sir?” The waiter’s voice is tentative—it’s a delicate moment. Sule’s widow, Hellen Wahu, is sitting at the Goshen Inn in Eldoret, crying a little as she remembers her husband. “Sule taught people to believe in themselves. That’s what he did, and he helped so many people,” she says. Wahu explains how Sule often visited an orphanage and how, later in his life, he informally helped support nine widows in Eldoret, visiting each woman monthly to deliver provisions like cornmeal and soap. His biggest contribution, though, involved teaching other African cyclists how to flourish. “Sule showed them it’s not about what a sponsor can give you,” Wahu says. “It’s about what you can do for yourself right now. He had so much hope.”

I’ve come here to Kenya to gauge whether Sule’s hopes for Team Amani can outlive him. In some ways, it seems like the answer is a certain yes. There’s the team’s 1-3 finish at last summer’s Overland. And a few months before that, while Sule was still alive, Meta, the parent company of Facebook, shot a high-action, minute-long ad that featured Amani riders swooping through both the Kenyan highlands and Zwift-like virtual realms as it suggested that technology can bring equality in cycling.

Still, when it came to shaping a vision for the team’s future, Team Amani had been almost 100 percent Sule. The idea took root in 2018 when Sule began talking to an American human rights lawyer and amateur cyclist, Mikel Delagrange, who co-owns Lola Bikes & Coffee, a cafe in The Hague, Netherlands, where he worked for the International Criminal Court.

For years, the shop had sponsored African road cyclists, and the two men had conversations about whether road racing was a good fit for African riders. Africa has been home to road squads like Team Africa Rising and Bike Aid for well over a decade, and although they’ve attained a few shining moments—Eritrean rider Biniam Girmay won a stage of the Giro d’Italia last year while fellow Eritrean Daniel Teklehaimanot held the polka-dot jersey for four consecutive stages in the 2015 Tour de France—success has been sparse. At Delagrange’s suggestion, Sule began looking into whether gravel might be a better fit.

Still, Delagrange was hesitant to get involved. Having spent a decade working in Africa, he’d become disenchanted with international development projects. “They just reinforce the power dynamics of the colonial period. I didn’t want to be another American with a project in Africa,” says Delagrange, who now lives in Switzerland and works for the United Nations.

Delagrange’s take is hardly new. Critics of aid to Africa point out that while the World Bank has spent billions to foster development there, more than 50 percent of its projects—such as wells, schools, roads, and dams—have failed amid local chaos and corruption. Meanwhile, in Kenya, a nation renowned for its world-dominating distance runners, organized athletics still seems tied to European colonialism. Many elite Kenyan runners live and train in camps owned by companies based in Europe. And these camps have hardly engendered stability. Currently more than 70 Kenyan runners are banned from competing because World Athletics suspects them of doping. And the 2021 murder of world-class Kenyan runner Agnes Tirop by her husband and coach, Ibrahim Rotich, also Kenyan, has brought new attention to a troubling dynamic: Female athletes in Kenya are so vulnerable to attack by money-hungry men that a group, Tirop’s Angels, has formed to combat the problem.

Many argue that what’s needed in Africa are not boutique projects—bike teams, say, or fair-trade coffee schemes—but rather economic and political stability that’s built slowly, over decades.

But Sule’s visions for a gravel team were infectious. “They weren’t focused on the Tour de France,” Delagrange says. So he resolved that he’d be in the “back seat,” raising funds and helping with logistics, while Sule split his time between riding and masterminding Amani’s rise.

Between 2019 and 2022, as Delagrange landed sponsorship deals with Wahoo and Factor Bikes, among others, he made 20 visits to Kenya. In 2021, he and Sule headed up the inaugural four-day Migration Gravel Race, which saw top Europeans racing locals on the rubbly red dirt roads of the Maasai Mara, a Kenyan national reserve. (Sule finished second, beaten only by Dutch legend Laurens ten Dam, and then won the race in 2022.) They got East Africans entry into elite Zwift races and began planning a home for Team Amani.

Iten, population 42,000, is a mountain town in Kenya’s Great Rift Valley, where it sits an hour northeast of Sule’s native city, Eldoret, and plays host to numerous elite running camps. Sule and Delagrange planned to build a world-class cycling facility for the team. Called Amani House, it includes athletes’ quarters, replete with nine tiny parallel bedrooms and two bunkrooms. Next to the house, they envisioned a pump track to entice local kids into cycling, and a clubhouse containing a performance center full of Wahoo Kickrs and a bike-themed cafe that could lure tourists who might want to hire an Amani rider to guide them through the surrounding farmland and forests.

The Amani project seems viable, even to those acquainted with the challenges of growing cycling in Africa. “Other teams, they’re looking for shortcuts,” says David Kinja, who’s been coaching with Safari Simbaz, a Kenyan development group, for two decades. “They think they can just turn Kenyan runners into cyclists, but there aren’t shortcuts. You have to build a culture, like they’ve done with running here, like they’ve done with cycling in Italy.”

Amani is working on that, Kinja believes, with the pump track and with plans to give bikes to local kids and host weekly races. “They’re being smart,” he says. “They’re not wasting lots of money on travel. They’re doing virtual races. They’re letting their riders stay home and face the world.”

Delagrange attributes Team Amani’s savvy to Sule, whose early life demanded resourcefulness. “He listened. He observed. He studied everything—course routes, nutrition plans,” Delagrange says. “He brought intelligence to everything he did. Nobody can fill his shoes.”

Last September, after Team Amani buried Sule in Iten, Delagrange spent four hours with the riders, equivocating over whether the Amani project should continue. “I told them, ‘I don’t want to do this alone,’” he says. “I asked them, ‘Can each of you pick up a piece of Sule’s mantle?’ And they said yes. It was the silver lining to a bottomless pit of sorrow.”

By the time I visit in December, Team Amani is still in a transition phase. The pump track is finished, a jet-black ribbon of asphalt swooping across the red earth. Groundbreaking for the athletes’ house is slightly delayed. And the team is still without an official captain. “Sule’s absence is forcing others to lead,” Delagrange says. But the group is widely dispersed. Several of the 11 riders live in Iten, but Olympic mountain bike hopeful Nancy Akinyi is in Nairobi, six hours away, and others are in Uganda and Rwanda. It’s impossible to discern whether one of them is quietly leading or whether there’s a power vacuum steeped in sadness.

In many ways, Iten is a typical Kenyan market town. Women sit on the ground downtown, selling socks and underwear and used T-shirts as motorbikes weave amid trucks spewing black clouds from their tailpipes. But Western tourists are everywhere, nearly all of them runners on pilgrimage to their sport’s holy land. You see them out on the chaotic streets, doing errands or sipping cappuccino at the High Altitude Training Centre, an athlete-focused retreat founded by world champion runner Lornah Kiplagat. The hills and forests are nearby, sometimes enchantingly blanketed in fog.

John Kariuki, last summer’s Overland winner, lives and trains in Iten, and when he and I meet for dinner, his manner is suave, nonchalant. A slight, wiry man, deep-voiced with a bushy beard, he begins by telling me he’s a country music aficionado, a fan of Johnny Cash and Dolly Parton. At the U.S. race just before Overland—SBT, in Steamboat Springs, Colorado—he persuaded Delagrange to buy him a cowboy hat at a Western apparel shop. Then his eyes alighted on a pair of leather boots. “If you buy me those boots,” he told Delagrange, “I’ll win Vermont Overland.”

Delagrange acquiesced, and, about 20 miles into Overland, Kariuki thought of the boots as he surged into the lead. Pay the boots! he said to himself. Pay the boots! The words danced in his mind like a mantra as he rattled over roots and rocks, never once getting passed, until he finished with a four-minute lead over runner-up Adam Roberge, a Canadian.

In the wake of that victory, Delagrange began to see Kariuki as Sule’s heir apparent. “He has a quiet confidence,” he says.

Kariuki grew up in Nakuru, a city of 421,000 situated about 100 miles southeast of Iten, where, he tells me, shrugging, his earliest years were “average, not rich, not poor. I had shoes. Most of the kids around me couldn’t afford them.”

Kariuki left school in 10th grade and then landed an apprenticeship with an auto mechanic. He commuted to work on a battered mountain bike. One day in 2015, as he was riding along, a roadie zipped by him—a Black rider, all kitted up. “I’d never seen a road bike, and I couldn’t believe that someone was going faster than me,” says Kariuki, then an avid soccer player. He chased the guy up a hill, and after they reached the top, nearly even, both gasping, the roadie suggested Kariuki join Kenyan Riders. “That’s when I started training full time,” Kariuki says. “It was a tough decision to quit my mechanic job, because I didn’t know if cycling could pay the bills.”

I ask him if he thinks East African cyclists can accrue superstar status and become visible in the bike world. “At most races,” Kariuki says, “we’re the only Black riders out there. I think people will pay attention. I hope they will.”

I spend a week in Iten meeting other Amani riders, each with a story. Twenty-year-old Joel Kyaviro came of age amid civil war in Congo. “In 2012, when I was 10, a bomb fell into our home and killed one of my brothers,” he says. “Every time fighting broke out, we ran into the bush and hid.”

Salim Kipkemboi, 24, is from the countryside just outside Iten. When he was 10 years old, he had to quit school. He began selling firewood by the roadside. He cut trees down with a handsaw, chopped the wood and then, when he had enough wood to sell, he made four or five trips a day out to the road two kilometers away with a large sack of it on his back. His life was so focused on survival that, he says, “I didn’t even know Nairobi existed.” His muscles were honed, though, and Kenyan Riders discovered him when he was 13. He has now raced in more than 20 countries.

It’s early December, and the Amani riders are tapering in preparation for the first Kenya National Gravel championships, set for December 18. The event is hosted jointly by Amani and the Kenya Cycling Federation, a controversial—and, some argue, tradition-bound—group that has had the same chair, Julius Mwangi, for more than 30 years.

The 63-mile race is open to all comers, with an entry fee set at 500 Kenyan shillings (around $4) to welcome the masses. It seems likely that a large contingent of European and American expats will show.

What do I have to lose? I sign up, and soon Kariuki is handicapping my chances as he sizes up my hunched 50-something physique. “You’ll definitely beat all the other mzungus,” he says, invoking the Swahili word for white person. “They only train on the weekends.”

Generously, the Amani guys let me tag along on a few rides. It’s sunny most days. We’re almost on the equator, but we’re also up above 7,000 feet, so the temperatures are pleasant, around 65 degrees. Most of the children we pass as they walk to school are dressed in uniform-issue V-neck sweaters. Some wear parkas as well. Other kids, upon seeing our little peloton, sprint to the roadside to hail us. Kariuki revels in this heroes’ welcome. “Yeah, yeah!” he shouts to our small admirers in Swahili. “You guys are running fast!” When we encounter a group of children splashing about in a river, he shouts, “How’s the water?”

There’s an ease to these rides that’s refreshing. Back home, there’s always some goober pushing the pace or hyperfocused on gear or tire pressure. Here the focus is on the riding rather than on who has what component. Amani’s athletes all race on quality Factor bikes, sure, but when a part breaks, it might take three weeks for a new one to come. One morning, as I ride with Geoffrey Langat, once a top inline-skate racer and now an ultradistance specialist on Team Amani, the rear wheel on his disc-brake bike is out of commission. He’s replaced it temporarily with an old rim-brake wheel, the disc-brake calipers taped to his frame. “I just have to be a little careful on the hills,” laughs Langat, who’ll race the 350-mile Unbound Gravel XL in Kansas.

Later we pedal into the Bugar Forest, just outside Iten, as shafts of morning sunlight filter down through the conifers onto a narrow, winding dirt path.

As the race date approaches, I book a hotel room near the start line. Then one morning I get disappointing news: Kenya’s gravel championship race has been cancelled. The pandemic is in check. Why has this happened? I write to Delagrange. “Sule’s absence,” he responds, “has never been more acutely felt.”

Eventually I learn that negotiations between Amani and the Federation have been less than harmonious. Delagrange assumed that Amani’s riders were ironing things out, as Sule once did. He sends the Amani riders a rueful WhatsApp message apologizing for the cancellation. He writes, “It seems my efforts at delegation have failed.” The note appeases no one; it just irks the riders.

“It was last minute, just four days before the race,” Geoffrey Langat says one afternoon as we’re standing by the pump track. “People were already driving there. Mikel wants riders to have more responsibility, and we’re willing. But we’ve never done this before. Someone has to teach us.”

The riders’ discontent will diminish in a few days, like a lover’s temper cooling after a quarrel. But in this moment, it’s a very real part of the ambitious, stressful Amani juggernaut. “Sule was good at politics, at dealing with the Federation,” John Kariuki says. “But it wasn’t easy for him. Sometimes he had to train at night. Gravel racing in East Africa is a new thing. It’s like a baby. It needs special care.”

I ask Kariuki if he spoke at the long meeting after Sule’s burial. “Yes,” he tells me, “I said that we have to show the world that this is not the end of this team.”

Later that month, Overland race director Ansel Dickey sends out an 800-word email meant to stoke enthusiasm for the 2023 race. The note quotes the ancient philosopher Marcus Aurelius but does not mention Sule’s death. Kevin Bouchard-Hall, who spent seven lonely minutes sitting with Sule post-crash, is stunned. “There wasn’t even a mention,” he says. “Not a word.”

“I can see why Kevin responded as he did,” says Dickey, when I reach out for comment. Sule’s death, he says, was a “new and terrifying experience for me, and I’m still trying to decide what’s the best thing to do.”

When I speak to Mikel Delagrange, he makes Team Amani’s stance clear: “We don’t hold Vermont Overland responsible for Sule’s death.” He notes that after last year’s race, Dickey, who is primarily a filmmaker, released a poignant 16-minute film, Amani in America, that lingers on the triumph of the team’s stateside journey, delivering, for instance, a slo-mo take of Kariuki getting splashed with champagne at the Overland finish line. Delagrange calls it “a beautiful tribute to Sule.”

Delagrange is more focused on Amani’s future. He says he’s going to stop pressuring the riders to assume the tasks Sule handled. He says he wants “everyone to bring to the project the gifts that they have. They have a world of capacity.”

Hellen Wahu, Sule’s widow, has computer skills. She honed them long ago, after Sule helped her land a job at a print shop, and in March she relocates from Eldoret to Iten so she can work part time for Team Amani, coordinating the construction of its new buildings. Her kids are enrolled in Iten schools now. One morning, she sends me a video of her oldest child—Lance, 11—ripping it up on the pump track.

The athletes’ quarters are now built and slated to open in June. Delagrange is seeking $200,000 in corporate funding for the performance center. He’s hired support in Kenya to assist with team management, a nutritionist from Harvard University is volunteering time, and the team is in talks with several coaches. Meanwhile, as I call Delagrange every few days, he keeps talking about a new visionary, a young cyclist named Jean Hubert, who was born in Rwanda during the country’s 1994 genocide, in which more than 800,000 people, mostly from the Tutsi ethnic minority, were killed by Hutu militias. University-educated and bike-crazy, although not a racer himself, Hubert, 29, still lives in Rwanda and runs a startup that makes apps.

Along with Delagrange, Hubert is intent on giving Sub-Saharan cyclists autonomy. “Most of these riders, they’ve never finished high school,” he says. “Their lives have been difficult.” In his nation’s capital, Kigali, under the auspices of Team Amani, he’s just opened Spoke Academy, which will see a few Rwandan cyclists spending six months learning communication skills—how to send emails, for instance, and how to network with sponsors. Eventually Amani hopes to have 30 teen riders studying at the Academy. “We don’t want to just look to mzungus for our future,” he says, explaining the focus on education.

Hubert is now on Amani’s board of directors, and he plans to replicate Spoke Academy in Kenya. “Sule was my friend,” he explains. “We’re indebted to him. We have to make sure we finish what he started.”

Still, I have to wonder: Will the team ever completely shrug off the scars of its founder’s death? Can it eventually sail smoothly along as it endeavors to carry young Africans beyond the pain and fragmentation wrought by colonialism?

One morning I have a long conversation with Hubert. He shares that he lost his father in the genocide and that his schoolmates, many of them orphaned, turned to drugs and alcohol. I come away feeling that I’ve been misguided in looking for Team Amani to transcend Sule’s death. The pain and the fragmentation that shrouds this team may last in some form forever. What’s meaningful is the struggle away from it, no matter how lurching, no matter how flawed and how human.

“We will keep asking riders to take the lead,” Hubert says. “We want to build citizens that have confidence in themselves, and that’s hard to do—the donor mindset is very rooted. Unrooting it will take a long time. But it will happen. Trust me. It will.”

For more on Team Amani and how you can support its efforts, visit TeamAmani.com.

You Might Also Like