I’ve spent most of the summer spying on my next-door neighbors. It’s not particularly dignified—especially since I’m literally peeking through my horrible kitchen blinds—but what else do you do when you’re stuck in an apartment by yourself all day? My neighbors’ eldest son is a competitive swimmer, who spent the early part of summer doing “laps” via a resistance harness in an above-ground pool the family set up in their small Queens backyard space, which is when I became fascinated by people I had never paid attention to until a pandemic forced us all to stay home 24/7. This situation reminded me of Daguerréotypes, Agnès Varda’s 1975 documentary about her humble shopkeeping neighbors on the Rue Daguerre—a film shot within 300 feet of her apartment because she couldn’t be away from home while caring for her young son. Rather than allow her frustrating physical constraints to limit her, she used them to propel her creatively and to make connections with others. The resulting film is warm, humane, and a little cheeky—not unlike the director herself. It proves how little we know about the people in closest proximity to us unless we look closer.

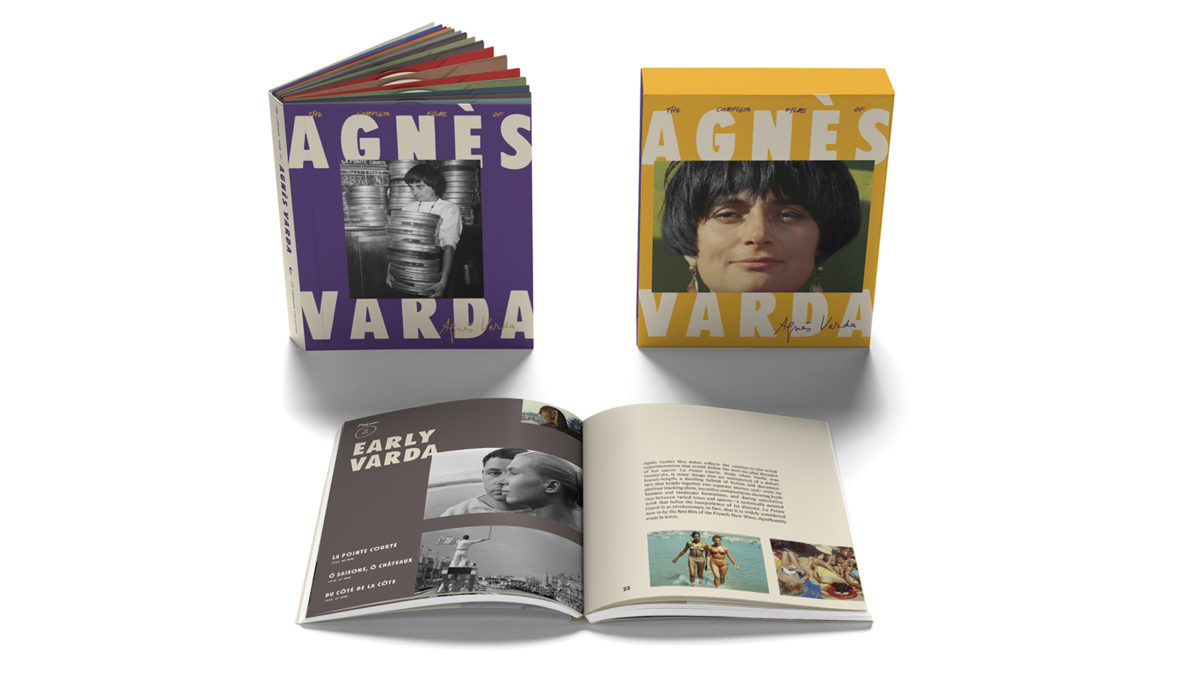

Throughout her life and career, Agnès Varda exhibited an intense curiosity in people, especially those overlooked by society. Wherever she pointed her camera, she found a story, and often, she became part of it, blurring the lines of reality and imagination. To watch her films is to not only know the people in them but Varda herself. Criterion’s gorgeous new box set The Complete Films of Agnès Varda is both a comprehensive, complete look at the work of one of cinema’s most visionary icons and also a testament to her empathy and humanity as a filmmaker, artist, and woman. Packed with extras—including many Varda supplied herself prior to her death in 2019—the fifteen-disc collection also includes an immaculate 200-page book featuring essays, film notes, and photos. It’s a cinephile’s dream, yes, but Varda’s works are really for anyone and everyone—especially those yearning for real human connection during a fraught moment in the world where distance is required.

“I’m always game to go toward villages, toward simple landscapes, toward faces,” Varda tells visual artist and collaborator JR in their joyous 2017 documentary Faces Places. This simple statement also acts as a manifesto for her life’s work. Varda loved traveling and meeting new people—finding inspiration in chance encounters and enticing environments. Her delight in people and places is most palpable in her documentaries like The Gleaners and I, Uncle Yanco, Mur Murs, Agnès de ci de la Varda, and the aforementioned Faces Places (where people become places and vice versa). In all of these films, the local color blends seamlessly with her own in imaginative ways. Because she narrated the majority of her work, we’re also treated to poetic and/or droll commentary, which further bonds us to both the subjects and the director. It’s as if she’s constantly beckoning you closer and letting you in on a delicious secret.

There is an intimacy to all of Varda’s work—perhaps because she so frequently made herself a part of it. But it also stems from her deep empathy for others whether they are self-absorbed pop stars (Cléo From 5 to 7), iconic muses (Jane B. par Agnès V.), divorced single mothers (Documenteur), lonely wives (Le Bonheur), or marginalized groups (Black Panthers and Mur Murs). Certainly her leftist politics, feminism, and a degree in psychology strongly influenced her work, but she offered neither pity nor judgment in her films. In Varda’s world, you are always free (and encouraged) to be yourself.

This is particularly crucial for her tougher subjects like in her 1985 masterpiece Vagabond, which follows a young female drifter (Sandrine Bonnaire, who won Best Actress at the César Awards) in the weeks leading up to her death. Inspired by a real news story about a homeless person found frozen to death in a ditch, the film itself makes no judgments about its fiercely independent—some would say wild—female protagonist, but it shows how we form impressions and judgments of strangers from the briefest of interactions. By the film’s tragic end, we’re no closer to knowing Mona’s full story, but we see how she has impacted each person and connects them all. It’s Mona’s choice to disconnect from society in order to be “free” (another recurring theme in Varda’s work—especially with regard to women) but the film suggests we all rely on one another in the end.

What Agnès Varda seemed to understand better than most is there is so much more that connects us than separates us. She knew she could have been any of her film’s subjects, and in many ways, she was all of them—lending her voice and lens to those who go through life unseen and unheard. When I watch Varda’s films, I feel a swell of hope wash over me like a wave on one of her beloved beaches. They’re a balm for the ails of the present world where so much seems to separate us, including our own physical circumstances. Varda’s insatiable curiosity, innate empathy, and vivid imagination are—dare I say in 2020—contagious, and her films are a reminder there is so much to see if you dare to look closely enough at your surroundings.

Perhaps tomorrow, I’ll stop peeking through my windows and finally say hello to my neighbors. I can’t help thinking it’s what Agnès Varda would do.

The Complete Films of Agnès Varda is now available on The Criterion Collection.