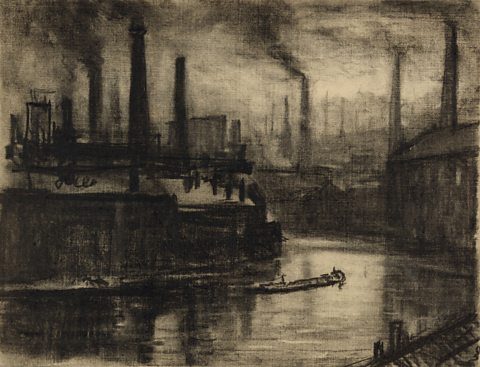

Coal and the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution that began in the mid 1700s made Britain an economic superpower and changed everyday life.

All of this industry required a huge amount of energy to power it. Coal was the fuel that provided that energy.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYWhy did coal mining develop in the UK?

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYAcross the world, coal had been used as a source of heat for thousands of years. It produced more heat and was cleaner than burning wood.

One important use of coal was the making of iron, another key material for the development of industry.

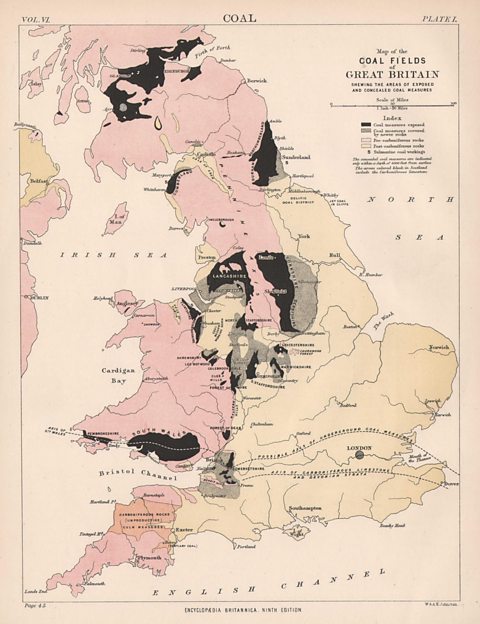

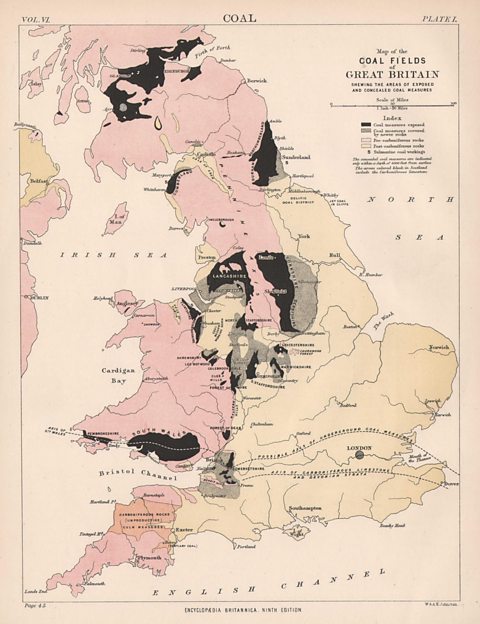

Britain had large reserves of good quality coal and it was mined in great quantities in the coalfields of Central Scotland, South Wales, and the Midlands and north east of England.

In 1881 alone, nearly 54,000 coal miners cut 20 million tonnes of coal from Scottish pits.

The majority of this coal came from mines in Lanarkshire and Ayrshire (source: Scottish Population History from the Seventeen century to the 1930s, 1977).

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYHow coal powered new steam engines during the Industrial Revolution

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMY

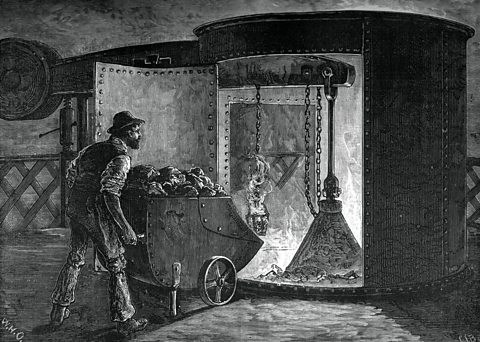

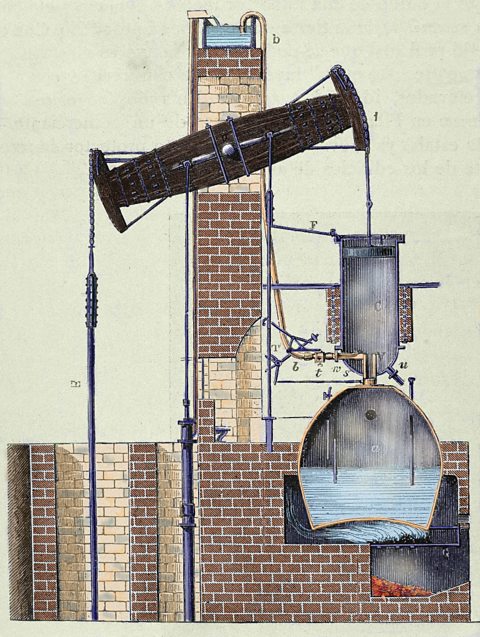

Steam-powered engines in coal mines dated back to 1712, with invention of the Newcomen engine – a device that used steam to power a pump that kept water out of mine shafts.

During this period Scotland became established as a major manufacturer of goods, as more and more textile factories sprung up to produce cotton, linen and wool.

On top of this, the construction of railways and ships to move the goods that the factories made required large amounts of steel and iron.

All of these factories, steel foundries and steam engines required vast amounts of fuel to power them. There was simply not enough trees in Britain to use wood. Coal provided the solution.

In the early 1700s around 3 million tons of coal were mined per year. By the 1830s, that had rocketed to over 30 million tons. (Source: A Short History of the British Industrial Revolution, 2018.)

How did James Watt's steam engine powered the Industrial Revolution?

Image source, ALAMY

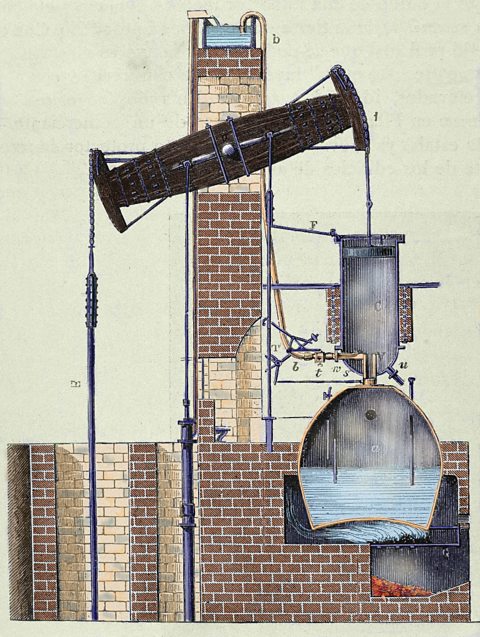

Image source, ALAMYJames Watt was born in Greenock in 1736. He worked making scientific instruments but, in the 1760s, he took an interest in steam engines.

In 1776, Watt launched his own steam engine. What made Watt's engine so revolutionary, was that far more efficient than other engines at the time.

Watt's steam engines helped power the Industrial Revolution and they were found in mines and factories all over Britain. The popularity of the engine made Watt a very wealthy man.

Coal mining during the Industrial Revolution

Image source, ALAMY

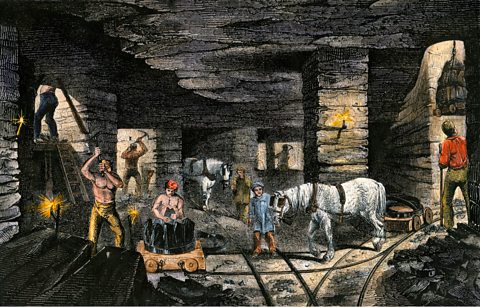

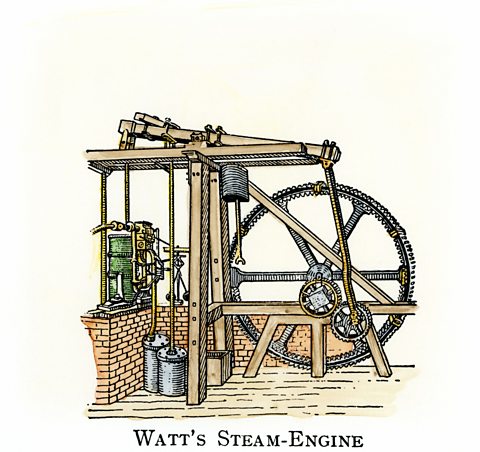

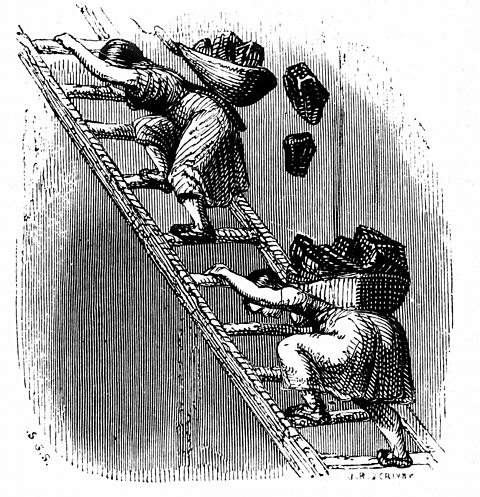

Image source, ALAMYCoal mining was often a family affair with different members doing different jobs in the mines.

Whilst the men were the hewers who cut or ‘hewed’ the coal from the seam, it was the women who carried or dragged the coal to the surface as the bearers.

Children played their part too. As they were smaller, their job as trappers was to open and close trap doors in the mine tunnels.

This would help improve the air flow by closing off some areas of the mine and moving the flow of air to where it was needed most.

Children also had jobs as putters. Once the hewers had filled a cart full of coal, it was the putter’s job to push it away to where it could be raised to the surface.

The families would live in houses close to the mines built by the pit owners. They would be charged rent on these houses.

Whole communities and town grew up around these mines and it was not unusual for several generations of the same family to grow up and work in the mines.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYConditions in the mines

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYAs the demand for coal grew, the mines grew bigger and deeper.

It was dangerous work because the mines were dark, damp, and cramped.

Not only was visibility and movement restricted but there was always the risk of severe accidents.

There were three main dangers of coal mining:

- flooding

- lack of clean air

- gas explosions

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYFlooding in coal mines

Image source, ALAMY

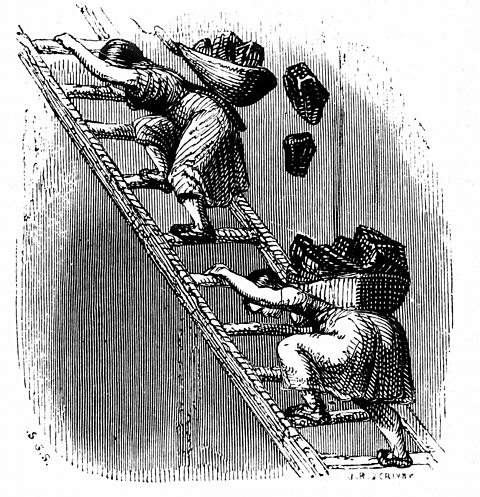

Image source, ALAMYCoal was dug out from underground layers called seams by coal miners.

To reach and dig out these seams, miners worked in long tunnels. These could be hundreds of metres under the ground.

The risk of flooding was a constant threat because water would collect in the confined spaces of the tunnels.

The water could cause the wooden support props to collapse, leading to the tunnels caving-ins – in some cases with the miners still trapped inside.

As miners had to dig deeper shafts to reach new coal seams, the risk of flooding increased as the pits went deeper than the Water tableThe water table is the underground boundary below the surface where water can be found. in an area.

Some of the tunnels even extended far out under the sea.

Deep mines relied on water pumps powered by steam engines to keep the mines dry enough for the miners to dig safely. If the pumps failed, the mines could flood quickly and miners could die.

Flooding remained a threat well into the 20th century - in 1950, over 100 men were trapped underground at the Knockshinnoch Castle Colliery in Ayrshire after an underground lake of liquid peat flooded into the mine shaft. Thirteen men died in the disaster.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYVentilation in coal mines

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYThe lack of ventilation would be dangerous because miners would not get enough clean air to breathe.

Miners could die if choke-damp gases (a mixture rich with carbon dioxide) replaced oxygen and miners could no longer breathe in the tunnels.

In 1862, a disaster at the New Hartley Colliery in Durham saw 204 men and boys killed after a mining shaft was blocked by falling pump machinery.

Many of the dead were killed by the build-up of poisonous carbon monoxide gas. The youngest of the dead were only ten years old.

Later, from the 1890s, miners would use canaries in the mines to detect the presence of deadly gases such as carbon monoxide.

The canaries had much smaller lungs than humans and if they died, it indicated the presence of dangerous gases in the air and they had to get out of the mine as quickly as possible.

Canaries were still in use in British mines until they were phased out in the 1980s.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYExplosions in coal mines

Image source, ALAMY

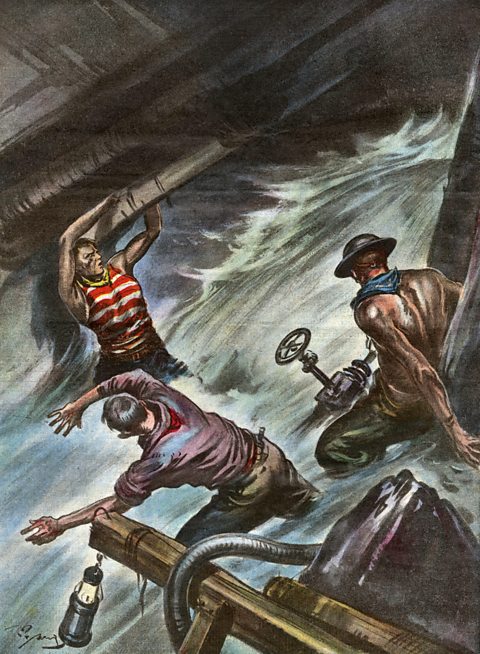

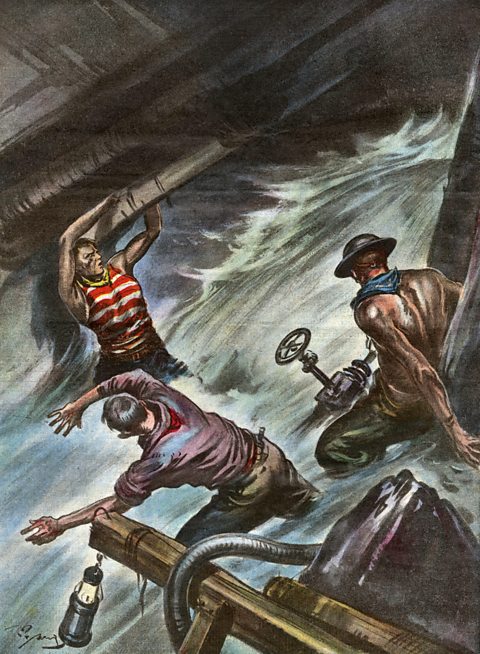

Image source, ALAMYGas explosions were another hazard as methane gas from the coal seams would mix with stale air. This mix, called firedamp, and could ignite causing fires in the pits.

This hazard was made worse when miners used candles for light. A candle flame could ignite the gas and cause an explosion.

On 23 July 1850, 17 miners were killed by a firedamp explosion at the Commonhead Colliery in Airdrie.

The rescue of some of these injured miners was delayed because of choke-damp (carbon dioxide).

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYCoal and the climate crisis

Image source, ALAMY

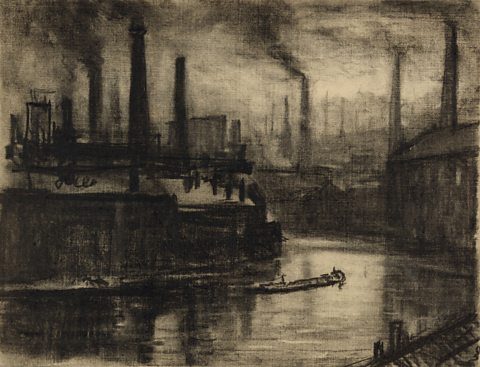

Image source, ALAMYThe reliance on huge amounts of coal as a fuel during the Industrial Revolution has had a serious effect on the environment.

During the early decades of the Industrial Revolution, the main concerns were pollution from the smoke and smog that the coal-fired furnaces created.

Then, in 1896, Swedish scientist, Svante Arrhenius, made the connection between the increasing amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and a rise in global temperatures.

Coal is a fossil fuel and burning it releases greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Over time, the build-up of these gases contributes to climate change.

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, it is estimated that humans have increased atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration by 48%, source: NASA: The Causes of Climate Change.

Image source, ALAMY

Image source, ALAMYTest your knowledge

More on Industrial Revolution

Find out more by working through a topic