The Brewers Building a Better — and Less Toxic — Philly Beer Scene

In 2021, the lauded Tired Hands brewery came under fire after allegations of toxic and discriminatory behavior. The brand is now tarnished, but what has risen in its wake may be even more impressive.

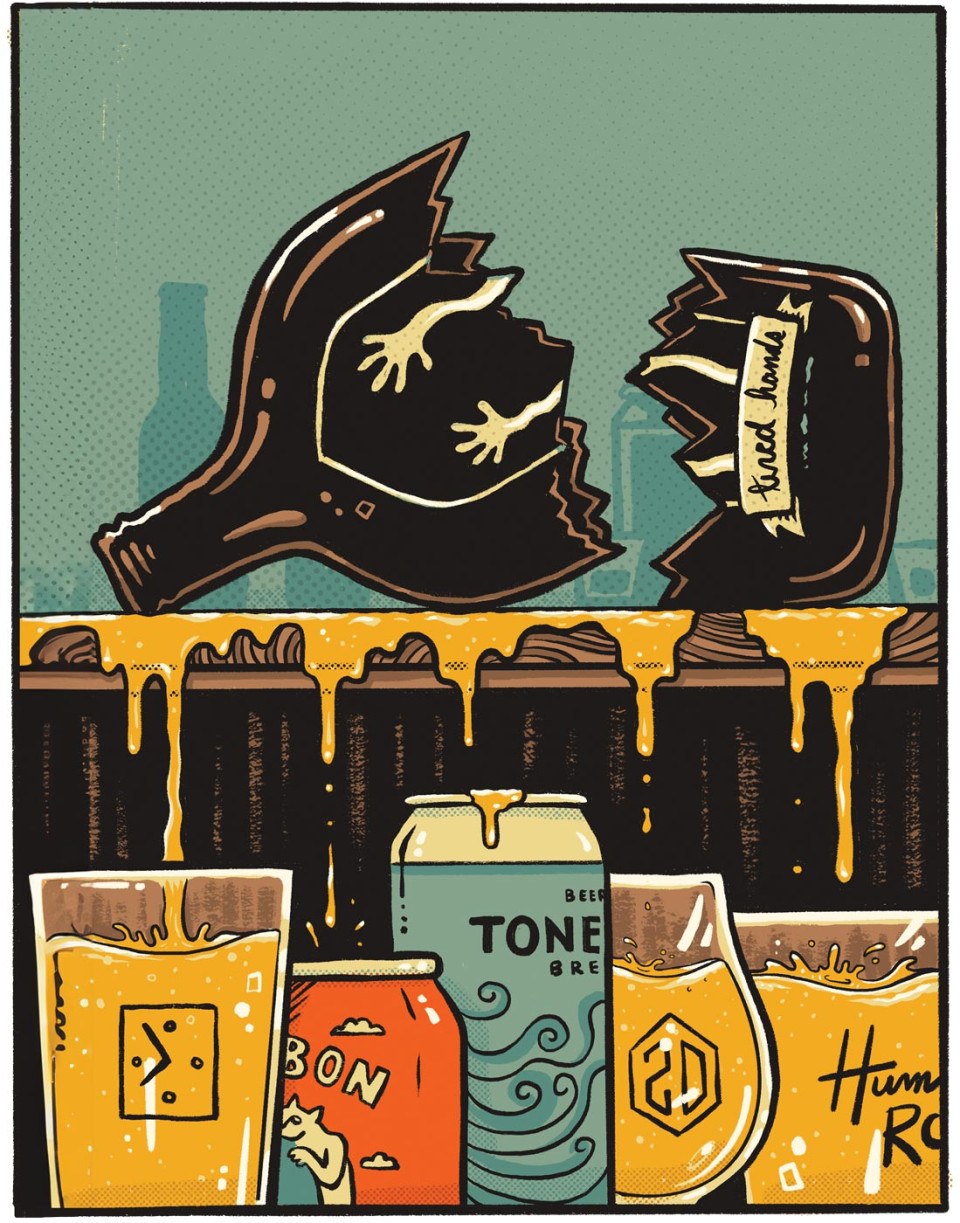

The Tired Hands diaspora that led to Philly beer scene’s revival / Illustration by Bruno Guerreiro

In May of 2021, it was like a rapture took place in the City of Philadelphia. The buildings remained in place, and so did the people. The sun rose and set, Phils fans still cursed the God who hated them, and clouds still fell as gentle rain.

What seemed to go missing was just about every Tired Hands beer tap within city limits.

Tired Hands Brewing is Pennsylvania’s most loved and hated and puzzled-over beer company of the past decade — a self-consciously eccentric brewery in the tony Philly suburb of Ardmore that makes high-octane, single-origin coffee stouts and hoppy ales the color of orange juice that might be loaded with rhubarb or graham crackers. Much more quietly, it’s also brewed some of the most subtle and lovely barrel-aged farmhouse beers to be found anywhere.

Opened in 2012 by a puckish enfant terrible named Jean Broillet IV, the brewery took wacky hold-my-beer experimentalism and hazy-IPA hype from cult status to the pinnacle of beer fame in America. James Beard took notice. So did Bon Appétit. And so did this magazine.

“Sorry for the cliché,” Philly-area beer writer and educator Tara Nurin told us last December. “But Tired Hands really did put Philly on the 21st-century beer map.”

That reputation crumbled in May 2021 after a talented brewer in Maine named Brienne Allan asked an innocent question on Instagram: Who else had experienced sexism in the brewing industry?

The result was a reckoning. After a torrent of responses, her Instagram account, @ratmagnet, became an anonymized conduit for hundreds of stories of abuse and unequal treatment told by brew staff all over the country, including accusations against craft-beer titans like Vermont’s Hill Farmstead and California’s Modern Times.

If Tired Hands stood out, it was mostly for the sheer number of allegations. More than a dozen anonymous stories zeroed in on the brewery and its co-founders, Broillet and Julie Foster. Subsequent reporting by beer blog Good Beer Hunting and the Inquirer centered on Broillet’s volatility; an environment where employees felt on edge and intimidated; and a “dude-bro culture” that led to perceived inequality in hiring and treatment.

Within days of the allegations, Broillet agreed to step back from leadership in a now-deleted public apology. (Foster had already stepped aside two months earlier.) Tired Hands staff staged what looked from the outside like a coup, declaring on Instagram that they’d “search for new leadership to build a stronger culture here.”

Tired Hands beer taps vaporized, seemingly overnight, at bars and restaurants all over Philadelphia. An exodus of staffers that had begun well before allegations went public now appeared to accelerate.

But as brewers who’d left Tired Hands found new opportunities, a funny thing happened: The Philly beer scene got better.

The most important players among the crew who made the most famous and beloved Tired Hands beers — from that first hazy milkshake IPA to gossamer-delicate saisons — are still making some of the best beer anywhere near Philadelphia. They’re just not making it at Tired Hands.

Their landing places include the two most exciting new beermakers of the past couple years: Carbon Copy in West Philly and Meetinghouse in Kensington. The same goes for Second District Brewing, an under-the-radar South Philly favorite tucked away on a side street almost too small for cars. Still more Tired staff are now at regional juggernauts like Tonewood, Human Robot, Vault and New Trail. Soon, former Tired Hands head brewer Juliana Disanti will start a brewery called Wild Fern an hour outside of Philly, in Frenchtown, New Jersey.

Consider it the Tired Hands diaspora. And it’s one of the biggest trends shaping not just what you’re drinking right now in Philadelphia, but what it means to be a brewer in 2024.

Talk to the brewers who worked at Tired Hands in its mid-2010s heyday and you get the sense the place was like the East Village music scene of the 1970s — a troubled and reckless place where talented people just happened to coalesce for a moment and make good things. Brewers arrived for all sorts of reasons, often recruited by one another and often with long and impressive résumés already behind them.

“I mean, it was the brewery to be at,” says Ben Potts, a former head brewer at the Tired Hands cafe who left to help found Second District Brewing, which opened in early 2017. “The trajectory was really skyrocketing. … But looking back on it with everything that’s come out, obviously there were problematic things going on that nobody was really paying attention to.”

This was the 2010s, craft beer’s modern cultural peak in America — a sudsy decade that saw the number of breweries in both Pennsylvania and America double and then double yet again. Outspoken brewer-owners like Broillet became celebrities to a newly minted generation of beerhounds. The Philly beer scene — previously known nationally for legacy German brewhouses like Yuengling and Christian Schmidt and world-class beer bars like Monk’s Cafe — became known instead for Tired Hands.

“Tired Hands was Philly’s first national/international hype brewery, where people would stand in line for limited-release beers,” says beer writer Nurin.

At former South Street beer destination the Cambridge in the mid-2010s, bartender Kevin Walsh used to watch Tired fans descend from all over the city to spend “hundreds of dollars a week” on Tired Hands beers — money they might not even have.

“They would be like, ‘I don’t have any money in my account till midnight. I get paid at midnight,’” recalls Walsh, a familiar bearded face at beer bars all over the city who now pours at Bardot and Pub on Passyunk East. Those broke bar-goers would then drink seven orange-juice-hazy HopHands while waiting for their checks to clear.

This meant Tired Hands could often choose which bars it sold to — and which it didn’t. A Tired Hands tap became a badge of merit for elect beer bars and a selling point for some of the city’s most prominent restaurants, from Pizzeria Beddia to Michael Solomonov’s restaurant group.

Those same renowned spots were among the first to drop Tired Hands when allegations became public, Broillet confirms when reached by phone. “People stopped serving Tired Hands beer,” he says, “and then just didn’t say anything about it.”

Records on beer site Untappd show the same thing happened all over the city: Tired taps blinked quietly out of existence, like expended stars. Among the city’s respected beer bars and restaurants, we found a scant few — just Tria and Glory Beer Bar around Center City — that still serve it.

“Now, it’s like if you have it, you’re seen as the ugly stepchild,” says bartender Walsh.

Ask Philly bartenders when and why their bars stopped selling Tired Hands and you get funny answers. Some who served it insist they never did. Some say the brewery was difficult to do business with. Some just don’t want to talk about it. One bar owner says, simply, “I don’t remember when it happened. It just stopped showing up one day.”

On a visit in January, Pizzeria Beddia — long associated with Tired Hands beers — was instead pouring Meetinghouse and Tonewood. Marc Vetri’s Fiorella was serving Carbon Copy and Second District. East Passyunk’s Fountain Porter was serving Industrial Arts, Carbon Copy, Tonewood and New Trail. All were made with the help of former Tired Hands employees. But none were Tired Hands.

At first glance, and frankly also at second glance, Kensington tavern Meetinghouse is the opposite of what you’d expect from a brewer who just left the trend-chasing fervor of a place like Tired Hands.

For one thing, there are just three house beers. One is “pale.” One is “dark.” One is “hoppy.” Remove the hops, and it’s the same list you would have found at New York’s McSorley’s Old Ale House for generations. Though it opened only last summer, in the former Memphis Taproom space, the blue-tiled corner bar feels almost unstuck in time, as though it was always here to serve cold beer and hot roast beef.

But if Meetinghouse looks like beer’s past, it might also look like its future — a blueprint for where beer is headed in 2024. Even as the beer boom flatlines into business as usual and beer giant AB-InBev gets better at shouldering regional breweries out of taps and grocery stores, the number of breweries is still increasing. But they’re beginning to look a lot more like local restaurants. As with other breweries founded by former Tired Hands brewers, Meetinghouse isn’t a hype monster or production machine. It’s a neighborhood public house, designed to serve its own particular community.

Here, co-owner and former Tired Hands head brewer Colin McFadden might personally pull you one of those three house beers. And if you ask, he’ll tell you why it’s special.

With his gentle demeanor, stray-curl beard and gray-flecked hair, McFadden has the air of someone who has wandered into the woods to find peace. He speaks about his beers slowly, thoughtfully, with near-punctilious precision, until you mention something he loves — a West Coast farmhouse beer he’d almost forgotten, that whiff of sulfur when you crack an Augustiner lager in Munich. Then, he sounds like an excitable child.

“I love sulfur,” he muses. “I love sulfur when it’s right. That’s a beautiful thing. That means it’s this young expression; it probably means the hops are going to be a little more lively overall. It’s gonna taste fuckin’ better.”

The bar at Meetinghouse / Photograph by Kae Lani Palmisano

At Meetinghouse, McFadden is chasing a vision he almost lost over the decade he brewed at Tired Hands, pumping out hazy IPA after hazy IPA using ingredients more familiar from a child’s lunchbox — strawberries, cotton candy, cookies. It wasn’t what he wanted. He even thought about giving up beer entirely. He promised his future wife for months that he’d quit, finally deciding in April 2021 that he’d give notice to leave in July.

Then, of course, all hell broke loose. He ended up hanging around weeks longer than he’d intended, trying to patch seams and pass on everything he knew to the people who planned to remake Tired Hands in Broillet’s absence.

But finally, McFadden got out — and back to basics. Meetinghouse’s beers are simple, subdued, drinkable, and also oddly individual. They’re all made with a Kölsch yeast, trapped between ale and lager, that brings out grassy and herbaceous aromas in the hoppy beer but evokes earth and mineral from an otherwise biscuity lagered pale that ranks among the finest in the city. Or there’s that fruity-rich dark lager, which tastes somehow like blueberry Dr. Pepper.

The tavern is too small for a brewhouse, so McFadden’s recipes are made instead at South Jersey’s blazingly excellent Tonewood, whose hoppy Freshies pale has become almost a default tap at good bars in Philly. There, he shows up on brew day to work with people he knows quite well.

“One of the best things, my greatest takeaway from my time at Tired Hands, was the talent that I worked with,” McFadden says. “And some of that talent is now at Tonewood.”

A brewer, the quality-control manager, the taproom manager — all are part of a network of Tired Hands refugees who’ve fanned out across the region and country. To Industrial Arts in New York. To the Veil in Virginia. To Freak Folk in Vermont.

McFadden doesn’t much like talking about Tired Hands or its founder, a quality he shares with other former employees we spoke with for this story. (For weeks, he shut down all conversation after his former workplace’s name was mentioned.) But he lights up when talking about the brewers he worked with there. McFadden gushes about Ben Potts’s subtle creativity at Second District. About Brendon Boudwin (a “wealth of knowledge”) and Kyle Wolak of West Philly’s Carbon Copy. People who make beer he cares about. People he calls “dear, dear friends.”

Those breweries, too, are busy revising what it is to be a beer maker in Philly — devoting world-class brewing talent to beers meant to serve their own South or West Philly neighborhoods.

Potts remembers his aha moment, soon after he began as Second District’s head brewer more than seven years ago. A couple customers sat down, looked at a list full of experimental beers, and asked for the most “normal” IPA on the menu.

“A light bulb went off in my head,” Potts says. His working-class South Philly neighbors didn’t want wacky. They wanted beer-flavored beer. Yet Second District remains sneakily experimental — making what McFadden praises as “palatable, drinkable” beers that are able to contain a “level of whimsy.”

Potts makes a full-bodied Czech pils as classic as it gets, but also skater-dad themed IPAs with hops that taste like a peach farm; bracing Belgian lambics that spend years developing more character than an alphabet; and a tannic, tiny-bubbled French grisette that might as well be barrel-aged champagne.

Like any South Philly Italian baker, Second District is all about the water, specifically the mineral-rich, semi-hard water from the Delaware that brings out crispness and bitterness in clean and clear West Coast IPAs. Potts builds his beers around that character — the character of Philadelphia.

By comparison, West Philly’s Carbon Copy might as well be a mad science lab. “We bought a water filter sized for a brewery four times our size,” said Carbon’s Boudwin, who worked in the lab at both Tired Hands and Modern Times. Boudwin, co-brewer Wolak, and former Tired Hands chef Bill Braun opened Carbon Copy in West Philly at the end of 2022.

Boudwin and Wolak filter their water until it’s a blank palette, then build it back up mineral by mineral to match the profile they prefer. Their crisp, lemony pilsner matches the pillowy softness of water in Pilsen, Germany. The floral, modern West Coast IPAs take on the savage mineral hardness of San Diego. The real Philly flavor comes from the buried generational secret of Philadelphia lagers, the bready Christian Schmidt Brewing Company yeast that dominated Philly beer for more than a century.

But to really understand Carbon Copy, look at its tap list. Alongside their mainstay house brews, nearly half the beers Carbon Copy introduced over its first year were collaborations with other brewers. Four were made with former co-workers at Tired Hands. Perhaps tempered by previous experience, Carbon Copy showcases a fanatical devotion to what used to be called “the beer community.”

“Relationships are everything,” says chef and partner Braun, the force behind Carbon’s long-proofed, crisp, character-filled pizzas. “You can nurture them and use them in a mutually beneficial way, or you can treat them as completely disposable — and once they’re of no use to you anymore, just throw them away.”

The new crop of beermakers is small, and bare-bones. But in their own ways, they’re trying to figure out what they owe to the people who work for and with them.

Potts, at Second District, says he had a dark night of the soul watching the industry-wide allegations play out across social media, even though he’d left Tired Hands years before.

“A lot of the stuff that came out was obviously true in terms of the male-dominated aspect of it and a lot of the sexual harassment issues around the industry,” he says. The allegations led to hard conversations with his girlfriend, a former bar manager at Tired Hands. He spent moments wondering whether he wanted to be in an industry filled with “megalomaniac owners who take all the credit and all the money.”

There’s a wide perception, he says, that Sam Calagione “brews every beer at Dogfish Head, and Jean brews every beer at Tired Hands.” But if Tired Hands was a great place to be a brewer in the 2010s, he counters, a lot of that came from the gifted people you got to brew alongside — people who have now gone on to lead other breweries.

Broillet, who quietly returned to his brewery in the spring of 2022, isn’t feeling apologetic these days. Any questions about the grievances of former employees would best be directed to former employees with grievances, he tells me: “I have a full HR department, I’m still not a shithead, and I employ universally great people. And I want to put myself in that boat, too. I’m also a very good person.”

Broillet says Tired Hands is doing as well as ever. The taprooms — there are six across the city and ’burbs — are busy. He keeps opening more, expanding into a mostly suburban empire. But the formerly cool-conscious brewery is now sending its beer to places previously unthinkable, whether that’s the shelves of Lehigh Valley wholesale barn Shangy’s, or a tap next to Miller Lite at a suburban New Jersey grill. Beer writer Nurin notes that even if drinkers are happy to order Tired Hands, it’s unlikely they’ll do so in Philly outside Broillet’s own taprooms.

“In the service industry, I believe there has been an immense and permanent change,” she says. Bars and restaurants are paying closer attention to who makes the beer they sell and how those brewers treat employees.

The new breweries are paying the same attention. Second District makes collaboration beers with staff, crediting bartenders and cooks for good ideas. Meetinghouse sells handcrafted goods from its bartenders at its in-house bottle shop. At Carbon Copy, the operators of a food truck out front selling decadent chopped cheese sandwiches also found part-time work at the brewery when they needed it. A cook and brewer there, Alyston Upshaw — who also tends bar at Meetinghouse — is starting his own beer brand, Concrete Blues, out of Carbon Copy’s brewhouse.

“We’re all kind of in this together,” says Carbon’s Wolak, “and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Soon they’ll be joined by another brewery from a former colleague. Juliana Disanti, head brewer at Tired Hands until last year, hopes to start Wild Fern Brewing with partner Derek Hunter in the little river burg of Frenchtown this spring. Disanti will be brewer and bartender, and she’ll serve simple, uncommonly good beers, same as the publicans of old. When the brewery hires staff, she hopes to make it the kind of place where she’d also like to work.

“I just want to have a warm, welcoming space and for everyone to be paid fairly,” she says, “and not treated differently for being different.”

Published as “After the Gold Rush” in the March 2024 issue of Philadelphia magazine.