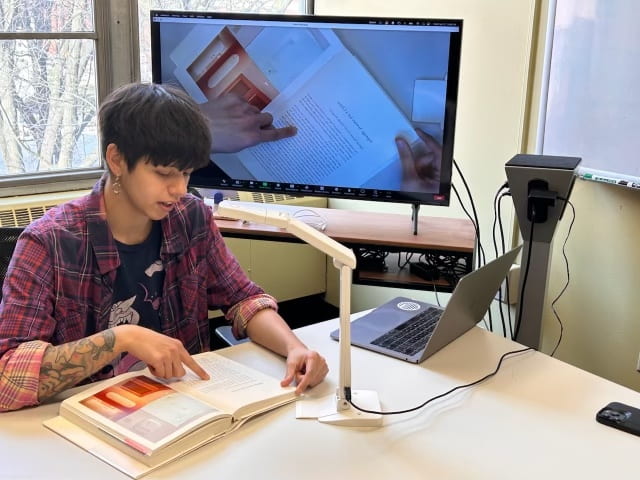

The “reader experience lab” was launched by the Department of English in January to gather data on how readers interact with and respond to verbal and written messaging. Credit: Christa Teston

Instructors, advertisers and politicians are always trying to find ways to make their message more clear, persuasive or attention-grabbing. A new lab at Ohio State may be able to provide more concrete answers.

The Department of English’s new “reader experience lab,” launched in January, is looking to concentrate on gathering direct data on how readers interact with, generate, interpret, analyze, comprehend and respond to both verbal and written messaging formats that are created by students themselves, Christa Teston, the director of business and technical writing in the Department of English, said. The lab is built into the business writing curriculum and is an official course in Denney Hall, but Teston said the lab has the potential to be reserved by researchers starting next semester.

Written messaging formats include documents, social media posts and messages created by students enrolled in the course.

“Sometimes I think students don’t know how to revise things in ways that are meaningful,” Teston said. “Having actual data from real readers is helpful to guide students as they revise their projects.”

According to Teston, the goal of the lab is to help students empirically test how efficient their messaging approach is, whether or not their methods are grabbing the attention of participants and if their documents are being interpreted correctly.

The lab can also be used to help instructors better detect artificial intelligence usage among students.

Teston said with the increasing use of AI amongst students in writing courses, the lab will allow students to bring in instructors to evaluate a stack of student work, half of which was produced by AI, and the other by humans. Through this process, instructors aim to discern which pieces were most likely AI-generated.

“We don’t really have a sense right now about how people are discerning the difference between AI versus human-generated,” Teston said. “I think there’s some pretty nuanced ways you can use AI to trick people, and collecting more data about what the cues are in texts that tip people off is a potential research project that could be collected or conducted in the lab.”

Teston said, however, that the overarching goal of the lab is to improve trust between the public and organizations — specifically the government and science — after the increased spread of miscommunication and disinformation during COVID-19.

“We’ve got a lot of work to do as communicators to rebuild trust with the various audiences and populations we want to protect and work with,” Teston said. “I think the RX lab is a very small space, but it’s one effort for that end to rebuild trust and create an opportunity for setting expectations about what things we can and can’t accomplish and what things actually mean.”

The Department of English’s business and professional writing course has fostered a longstanding partnership with the Ohio Sea Grant and Stone Laboratory, a statewide initiative dedicated to preserving the Great Lakes environment, Teston said.

Each semester, students enrolled in this course are responsible for crafting materials for the campaign, including devising social media strategies, designing infographics and engaging in a project titled “Emerging Media,” where students analyze social media platform trends to identify avenues through which the mission of the campaign can garner visibility through messaging.

Historically, students could not measure the efficiency of the documents they produced for the campaign. Teston said the establishment of the lab was built to address that issue, serving as a platform for students to receive feedback from external sources, beyond their instructors, regarding the effectiveness of their messaging in achieving their intended goals.

“[The RX lab] is a way to collect that data from real people in a private space, using cutting edge tools, for example, eye tracking software that allows you to see where people are looking, how long they’re looking at a particular example [and] how much people actually learned from engaging with the document,” Teston said.

The RX lab is a spinoff of UX labs, which primarily exists outside of academic spaces, like Microsoft and Google, to study user experiences of particular products, Teston said.

Typically, UX labs focus on the body’s response to stimuli, using devices such as heart rate monitors. The RX lab hopes to focus more on participants’ thinking, reactions and cognitive processes, according to Teston.

“We really hit hard qualitative, humanistic data points,” Teston said. “We’re interested in collecting data points that have to do with being a human, rather than just being a body in the world that sort of responds to stimuli. We want to hear from people and how they interpret and talk through their own understanding of messages that they’re engaging with.”

Beyond using research protocols that include directly talking to the participants, Teston said the lab contains a one-way mirror glass window, desktop computers and eventually, eye-tracking software next semester.

Costing roughly $30,000, the lab is supported by discretionary funds allocated by Dana Ranga, the dean of arts and humanities, and a portion of funds Teston received from winning the Ronald and Deborah Ratner Distinguished Teaching Award in 2019, Teston said.

The creation of the lab will influence students’ skill sets and capabilities as researchers, Elizabeth Velasquez, a graduate writing program assistant, said.

“Students who want to go into UX or RX research as a field can gain very hands-on, technical experiences through this lab,” Velasquez said. “I want students to think about audience experience and how things they create will be interpreted but also lived.”

Such designs include elevator and crosswalk buttons, most of which were installed despite automatically operating without a required touch in areas of high usage, Velasquez said. Velasquez used the example of a crosswalk button on Lane Avenue and High Street that does not work, as the light changes on a set schedule.

“[I am] trying to orient my students’ perspective in the fact that they live in a designed world and that world was designed intentionally to produce a particular feeling, moment or person,” Velasquez said. “People who design those environments, design elevators, design crosswalks, want to feed into the feeling that you have affected your environment, so you will become more patient with it as it attempts to do what it was always going to do.”

Beyond just students, Teston said the lab can be used by faculty outside of the course to conduct research and help determine the efficacy and effectiveness of assignments for faculty as well as the comprehensibility of documents, such as grant proposals, for local nonprofits.

“I’m also thinking about nonprofits around the area, who can’t afford to consult with usability labs and might just want to get some input about a brochure they designed,” Teston said. “They could just ping us, we set up a quick study with some participants, collect some data and write a one or two-page report about things we recommend about how they revise that brochure.”