Though he’s not afraid to die, a Sterling, Virginia, teenager with a rare genetic disorder is doing everything he can to stay with his family.

Ryan Alam, 15, is among fewer than 100 people in the world known to have the progressive neurodegenerative disease known as MPAN that’s a type of NBIA — neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation — disorder.

He and his family are hoping to spread awareness to help raise money for MPAN research.

“You can think of MPAN as a lot of horrendous diseases rolled up into one,” Ryan’s dad, Faisal Alam, said.

The effects of MPAN progress over years or decades and can be similar to Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. Symptoms can include vision changes, difficulty swallowing or loss of ability to swallow, having to use a feeding tube, speech impairments, muscle tightness, and inability to walk.

“It’s not like losing your kid to a car accident, or to cancer, or some acute condition. It’s sort of a long goodbye that we have to endure,” Faisal Alam said.

Ryan was diagnosed last November. Then, when MRIs and other tests confirmed MPAN in April, his parents told him.

“He cried at first and he asked us, ‘Does that mean I’m going to die?’ We had a long conversation about what the diagnosis meant and what the game plan was we were going to pursue,” Faisal said. “So, yeah — that was a difficult night for the entire family.”

Ryan remembers crying that night, but not because he was scared of dying.

“I just wasn’t ready for that news,” Ryan said. “I told my mom, ‘I didn’t want to leave you early. I don’t want to leave this Earth early.'”

He cried for an entire day, then “got over it,” Ryan said. His sister, 13-year-old Sonia, talks about how he never gives up when something puts him down. And his mom, Tuba, said there’s never a day when he doesn’t have a smile on his face.

“I like to spend time with my family and play with my two dogs,” Ryan said.

He’s also the kind of teen who doesn’t have just one answer when asked about his favorite subject in school. “Math, P.E., and science, and history,” he said.

Ryan also prefers confetti cake over pie, said visiting Mauritius in the Indian Ocean has been his most memorable vacation, and his last fabulously happy day was when he became part of the Potomac Falls High School football team.

And, he has attitude.

When the family was hiking at Kanarra Creek Canyon in Utah, Ryan’s mom wasn’t sure he could make it because of the water and uneven surfaces. Halfway down the trail, she suggested they turn back.

“He told me to take a chill pill,” Tuba said. “He said he was going to do it. [And] he did!”

Ryan’s doctor at Children’s National Hospital describes his family members as “forces of nature,” becoming advocates for him and the disorder he has.

“Right now, there is no treatment, there is no cure,” said Dr. Jamie Fraser, who’s an assistant professor of pediatrics at George Washington University and a medical biochemical geneticist at Children’s National Hospital.

“We don’t know how to treat the condition, outside of managing the symptoms.”

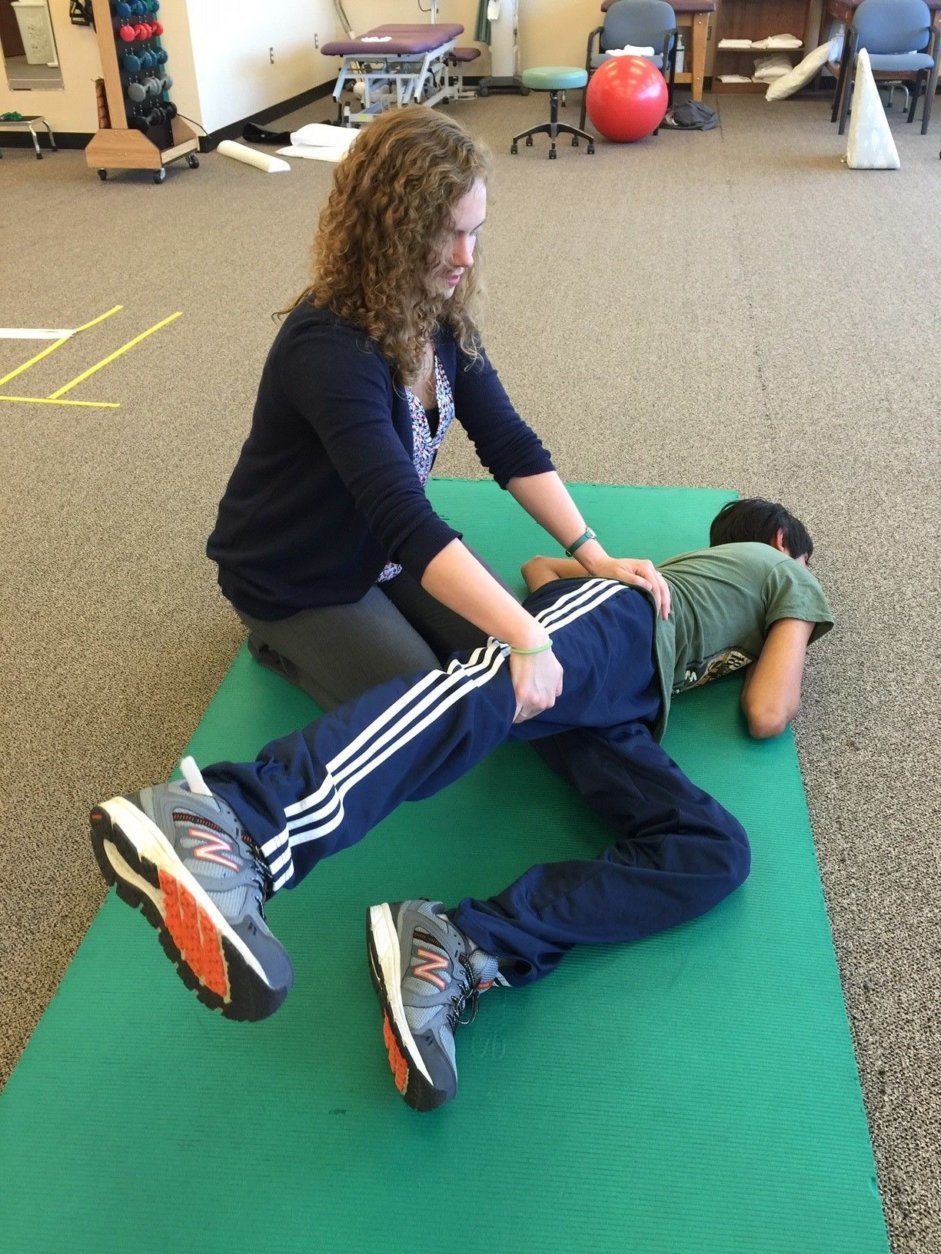

The effort to try to keep Ryan’s symptoms from progressing includes a grueling schedule of physical, occupational and speech therapies, and muscle tone management.

The 15-year-old works with a gym trainer one-on-one for at least an hour, three times a week on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays after school. His aqua therapy sessions happen once, sometimes twice a week, either at 5 p.m. after school or as early as 7 a.m. on Wednesdays.

Over summer breaks, Ryan takes speech, and he’s had an occupational therapist work with him. Through it all, he stays positive.

“He’s definitely very positive. His attitude is wonderful,” Tuba said. “He’s amazing. That’s definitely helping him get through all of this. He wants to get better, and he said he’s going to fight.”

Faisal talks about his son’s “indomitable spirit,” and how he is staying positive through all his trials and tribulations.

“He’s never complained about his situation. Even when we broke the news to him, aside from a little bit of crying that night — the next day, he was back to being Ryan and back to having a big smile on his face,” Faisal said.

An estimated $300,000 is needed to jump start MPAN research, Fraser said.

“Our goal and our research project here at Children’s is to find ways to stop the progression of the disease so that these children don’t have to continue to basically disappear in front of their families and live out their family’s worst nightmare when they have this condition,” Fraser said.

Children’s National Hospital also will be creating a program, inviting people with MPAN from around the country to come to the hospital to be evaluated by the clinical research team, to answer a multitude of questions about their health, medical needs, neurological status and to obtain samples that can be used to further research in the lab.

Fraser said big pharmaceutical companies are interested in rare disorders once there’s a way to treat the disorder.

“But, you have to know more about the disease before you can get an National Institutes of Health grant to study that disease, or before you can ask a pharmaceutical company to help support the work,” Fraser said. “We stepped into the void because there was a need and because we have expertise in rare neuro-metabolic disorders, both clinically and in the laboratory.”

You can find Ryan’s “Help Cure MBISA-MPAN” donation information here.

“Please donate to my fundraiser. Me and all the other kids with NBIA-MPAN could really use the help,” Ryan said.