- Known for its intoxicating scent, sandalwood has been a precious commodity for over 3,000 years, fuelling ‘sandalwood rushes’ into the 20th century

I got my first whiff of sandalwood 25 years ago, in a blend of burning incense at a tiny Buddhist shrine in Lopburi, soon after landing in Thailand from Los Angeles as a lowly English teacher on July 3, 1997.

Unlike other precious commodities of their time, such as silk, pepper, tea and gunpowder, the story of sandalwood is not well documented. But after being so quickly intoxicated by the incense smoke in Lopburi – my first day in Asia – over the next quarter of a century it would become a personal endeavour to explore the origins of the sandalwood trade.

To understand its roots, uses and the reasons sandalwood became so sought after is to trace it back more than three millennia, deep on the Asian subcontinent.

During the Vedic age, from 1500BC to 600BC, highly specialised doctors carried out India’s medical traditions, mixing medicine with magic and mantras. In the ancient Ayurvedic text, the Charaka Samhita, Indian sandalwood – known as candana or chandana in Sanskrit – is listed among 129 mono-herbal drugs, with 403 proscribed healing recipes for all kinds of ailments and conditions.

In the Ayurvedic prescriptive and surgical manual the Sushruta Samhita, the Raja Vaidya (royal physician) could prescribe sensual medicine baths to the king and “rich men”. One varietal, white sandalwood, is graphically described as a way to treat daha, a “burning sensation” associated with drinking too much alcohol, which involved cooling baths with touches from “maidens’ hands”.

Indian sandalwood was also used in a heady admixture of bark, flowers, fruits, grasses, herbs, roots and leaves that formed a healing and refreshing incense meant to be inhaled daily.

The sacred medicine then starts appearing more as a luxury good, in the eastern Mediterranean and around the Nile River, in Egypt. The Bible’s King Solomon (961-922BC), famed for his 700 wives and 300 concubines, constructed his temple with banisters made of “almug trees”, believed by some to be sandalwood, which was used to embalm Egypt’s elites in mummification rites.

The privileged across the region began listing sandalwood as essential possessions, and in the first passages of the Arthashastra political doctrine on statecraft, formed sometime between 1BC and AD1, aloeswood, sandalwood and other aromatic woods are said to have been essential to royal treasuries.

Back in Asia during the apogee of the Vedic world, a young Brahmin named Siddhartha Gautama (563-483BC) left his royal compound for India’s forests to wander and meditate. Having become enlightened under a bodhi tree, he founded Buddhism around 531BC and became known as the Buddha. His acolytes would later use sandalwood to calm the mind during their meditations and rituals.

The history of Zen and how the ancient religion became a capitalist darling

During India’s Maurya empire (320-187BC), sandalwood use accelerated, particularly under King Ashoka (304-232BC), who by ordering Buddhist edicts on stone pillars across India and sending monks to Central Asia and Sri Lanka, advanced the faith, which required more sandalwood trees for incense.

During this same period, new ports emerged around the Indian Ocean – on the coasts of Coromandel (southeastern India), Sri Lanka, the Malay Peninsula and Java – cultivating a network of Buddhism, Hinduism and commerce.

This history was unknown to me when I bought a sandalwood-scented beaded necklace while backpacking through the southwest Indian state of Kerala, in 2000. I was just as clueless about the famed “sandalwood flower” coins found across what is now Indonesia, when I visited the temple most famous for their use later that spring.

What are ‘sponge cities’? How China is leading fight against urban flooding

From the late 8th to the mid-9th century, metal coins bearing sandalwood flower prints were minted by the state of Mataram, in central Java. These were flat or scyphate (cup-shaped) and minted from gold, electrum, silver or silver alloy.

These coins were used in successive states from Mataram in the 9th century to the Majapahit empire in the 14th, for trade, taxation or as offerings in shrines for holy rites: they were closely associated with Borobudur, in Java, the largest Buddhist temple in the world. But I knew nothing of this history on my trip there in 2000.

Panels on Borobudur illuminate a rich telling of locally detailed Indian Buddhist tales. They suggest key sandalwood sources from the Lesser Sundas and Timor flowing into east Java – and why, in 1226, sandalwood from Timor was being bought by Chinese merchants.

Chinese appetites for sandalwood from Indian and Javan markets were whetted by the grand expansion of Buddhism out of India. After King Ashoka’s 261BC edicts for Buddhism saw missionaries enter Central Asia and eventually China, the faith grew gradually over the centuries across the early Silk Roads.

Buddhism’s most prominent arrival in China began in earnest in AD68, during the Eastern Han dynasty, and took greater hold in AD220, all the while scented with sacred sandalwood.

Buddhism brought an entirely new kind of scent culture to China, based on aromatics from the Indian subcontinent and olfactory theories developed there over many centuries. The role played by scents in Buddhist thought is profound; the Sanskrit term gandha means both “aromatic” and “pertaining to the Buddha”.

HK$10 million worth of protected wood seized in Hong Kong customs operations

From India, Buddhist candana would find a sweet spot in Chinese cosmology with the character 香, or xiang, which as far back as 239BC denoted sweetness and a cosmological centre of nature’s cycles in China.

In the Qin dynasty classic work Lüshi Chunqiu 呂氏春秋 (Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr Lü) and Han dynasty work Huainanzi 淮南子 (Book of the Master of Huainan), xiang 香 plays a prominent role.

This may have been the time when the first part of candana was changed into either an ideograph or portmanteau with the character tan 檀. As a meaningful word, it was juxtaposed with xiang 香 as tanxiang 檀香, and with the character mu 木 for wood, tanxiangmu 檀香木.

Both can be used for sandalwood in Chinese. The character mu 木 can also be replaced for other meanings, such as the character for mountain, shan 山. Many centuries later, tanxiangshan 檀香山, or Sandalwood Mountain, became the original Chinese name for Hawaii, when sandalwood was shipped from the islands to compete with Indian sandalwood in Guangzhou in the early 19th century.

Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang’s 7th century account of his 19-year odyssey (AD626-645) across Central Asia and India to explore Buddhism brought to China the tale of the Sandalwood Buddha: a legendary “living image” of Buddhism’s founder carved from a single piece of sandalwood, which some consider the first, and one of the only, images made of him during his lifetime.

Later, the tale would be transmitted from China and Korea to Japan, inspiring a desire for sandalwood there also. Of the seven Buddhist statues Xuanzang brought back to China, four were made of sandalwood.

Sandalwood Buddha traditions in China continued from the 7th century, facilitating two particular examples that had a lasting effect. One became a palladium, a national treasure that protects the state and the ruling dynasty, and travelled in China, transmitted or stolen from one dynasty to another. Eventually, the sandalwood statue arrived in 1163 in Beijing, where it remained until 1900.

The Chinatown Stalin made a ghost town: Millionka in Vladivostok

Within a century of Xuanzang’s work, Chinese and Japanese monks began in earnest the tradition of Buddhist danzō (the Japanese word for sandalwood images) and dangan (Japanese for portable sandalwood shrines). This tradition would last from roughly the 8th to the 14th centuries with sandalwood culture ever deepening.

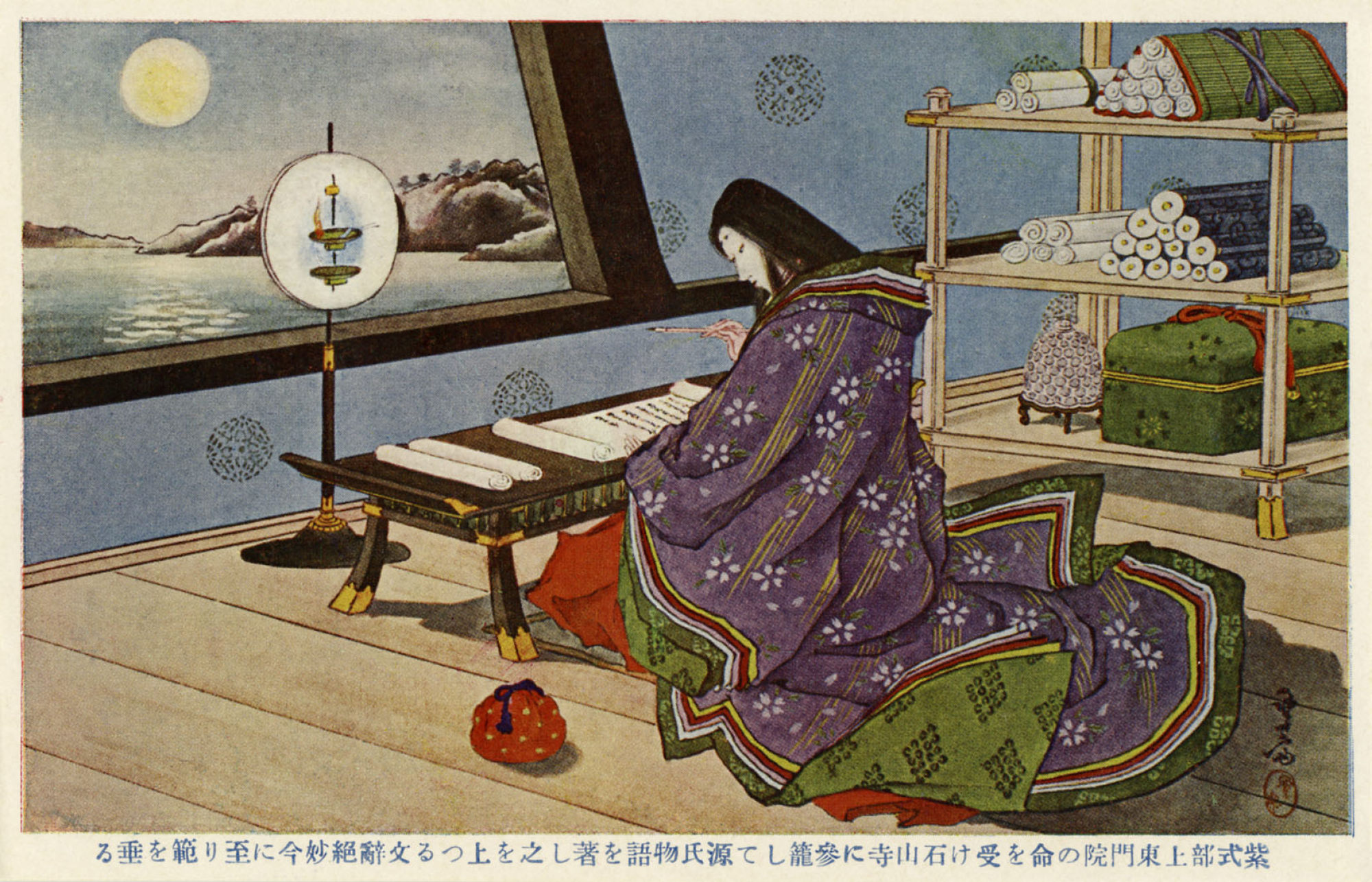

The Tale of Genji, by Lady Murasaki Shikibu, published circa 1021 and considered the world’s first novel, notes: “Her Cloistered Highness’ personal chapel, Genji has sacred images (jibutsu, that she will always have with her and the object of her daily devotions) dedicated in summer, when the lotuses are in full bloom, to which he added banners (hata), flower-stand covers, a ‘Lotus mandala hung at the back’ as well as statues made of white sandalwood of ‘Amida and his two attendant bodhisattvas’ (Kannon and Seishi).”

The Tale of Genji also notes the high culture of incense contests known as Kōdō (香道), or the “Way of Fragrance”, a tradition that became as meticulous and precious as Japanese tea ceremonies. Sandalwood, called byakudan in Japanese (白檀) along with aloeswood and camphor were the most important woods used in the Kōdō.

The Japanese character byaku 白 means white and the character tan 檀 stands for sandalwood – borrowing the Chinese character from the earlier combination of tanxiang 檀香 with distant echoes of the Sanskrit candana or chandana.

An author of the Golden Age of Incense, court official and poet Minamoto Kintada (AD889-948) described his famous incense blend, Lotus Leaf, as:

“Spikenard: one bu

Aloeswood: seven ryo, two bu

Seashells: two rye, two bu

Sandalwood: two shu

Mature lily petals or musk: two bu

Cloves: two ryo, two bu

Benzoin: one bu”

Of course, the demand and supply of sandalwood in northern Asia, India, the Middle East and Southeast Asia ceased to be a regional secret once the sea-conquering Portuguese sailed into that part of the world.

Following the capture of Malacca, in 1511, the Portuguese gradually moved from southwest Malaysia and engaged southern China, establishing a settlement in Macau, at the western mouth of the Pearl River, in 1557, and trading upriver to Guangzhou.

After the Dutch seized Malacca, in 1641, the Portuguese made Macau a permanent home from which to dominate the sandalwood trade: the Macau-Timor route would influence the flow of sandalwood into coastal China, primarily the Pearl River.

The Dutch would come for sandalwood in the Lesser Sundas, occupying Solor in 1646 and establishing Kupang, in West Timor, in 1653, giving the Portuguese a run for their money.

Inner Mongolia captured in photos by native who finally realised its beauty

Although the Dutch did not dominate the sandalwood trade into China in the same way as the Portuguese, they gained a monopoly to ship it directly into Nagasaki, Japan, where they had firmly entrenched a port and trading post.

The Chinese were never fully cut out of the trade, buying and selling it back in coastal China and into Japan. The new coastal markets in East Asia saw Macau and Guangzhou rise as key markets for both raw and refined sandalwood coming from the Lesser Sundas, particularly Timor – doubly so after 1644, when the Qing dynasty emerged with global ambitions and greater sandalwood demands.

A century later, in the 1740s, Emperor Qianlong began renovations to Yonghegong Lama Temple, in Beijing. When the seventh Dalai Lama, Kelsang Gyatso (1708-1757), found out, he sent the emperor a costly and impressive gift – a sandalwood tree trunk.

Kevin Greenwood, historian and curator of Asian art at Oberlin College, in Ohio, in the United States, notes the tree trunk that became the mighty Maitreya Buddha statue, which still stands in Beijing’s Yonghegong Temple, was “purchased from the Gurkha king in Nepal and transported through Tibet, Sichuan province, up the Yangtze River and Grand Canal, arriving in Yonghegong in 1747”.

The Maitreya was assembled and gilded in the Pavilion of Infinite Happiness, and was joined by three smaller white sandalwood Buddhas in Yonghegong’s Hall of Eternal Protection. The Buddhas of Longevity – the Medicine Master Buddha, Amitàyus Buddha and Simhanada Buddha – each stand 2.35 metres tall. Their origin was also likely by the same route as Maitreya – from India via Nepal to Tibet – using natural and man-made waterways to reach Beijing.

Back in India, during Qianlong’s reign, the East India Company set its sights on lucrative sandalwood. Tipu Sultan, the ruler of the kingdom of Mysore, defended what is today part of the states of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu from British invasion during the Anglo-Mysore wars, from 1767 to 1799.

So much for British ambitions of selling Indian sandalwood to China. Then, in 1804, came news of Sandalwood Island – Vanua Levu, in Fiji – and British ships set sail from ports from Calcutta to Port Jackson, Australia. American ships also flooded in from New England, mainly selling guns in exchange for sandalwood.

Sandalwood rushes occurred across Oceania, often leading to depletions: the Marquesas (1815-17), Hawaii (1810 to the 1830s), New Caledonia, the Solomons, Vanuatu (1840s to 1860s), and Western Australia (1860s to 1880s). In fact, Western Australia saw more booms well into the 20th century.

Are Macau’s days as a global gambling hub numbered?

The Indonesian island of Sumba opened up after World War I, until the sandalwood was exhausted in the 1920s, leaving it awash with tiny transport horses called “sandalwood ponies”.

Sandalwood from Polynesia, especially Hawaii, travelled aboard American ships, while wood from Melanesia was mainly transported on Australia-based ships under British flags, nearly all sailing to Guangzhou, where it was transported nationally or manufactured locally into furniture, decorations, traditional Chinese medicine or incense.

Post-colonial forest policies have seen massive exploitation and the species itself threatened – severely so in India, where sandalwood was almost wiped out by 1974, as the environmental historian Ezra Rashkow has written.

Conservation movements and scientific studies in the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s failed to stave off widespread poaching or the sandalwood mafias of India, Indonesia and East Timor. Thankfully, since the ’90s, forestry projects and private businesses have been able to innovate exogenous plantings across Southeast Asia, Vanuatu and Australia.

Are Scientology founder’s far-fetched tales in China diaries actually true?

The vast and sacred history of this tree, spread across this wide canopy of time, has been a constant interest during my decades in Asia, and cataloguing it helped keep me sane while boxed up in Macau and Beijing during the first year of the pandemic.

When I caught Covid-19, I was grateful that I never lost my sense of smell. And when I finally left China, free to light sandalwood incense on the beaches of Thailand, I remembered where my sandalwood story began, not so far away, 25 years ago.