Lotusland gardens a dedicated stage for over-the-top botanical beauty

Born from the vision of a determined opera diva, historic Montecito property lives on as an oversize tribute to plant lovers

When Carlsbad resident Sharon Corrigan visited the 37-acre Montecito botanical garden Lotusland with the San Diego Horticultural Society, she was bowled over.

“I’m not one to remember botanical names of plants,” Corrigan said, “but I was enchanted and excited by plants I knew as houseplants that were in the ground at Lotusland and towered 20 or more feet over my head. It is hard to describe the charm of wandering around the property not wanting to miss anything and being constantly surprised. I grew up near Huntington Gardens and the L.A. Arboretum and, although I love them both, Lotusland is over the top.”

Lotusland was the creation of the flamboyant Madame Ganna Walska — the stage name of Polish singer Hanna Puacz. Married six times and with an estate near Versailles, outside of Paris, Walska was encouraged by husband number six, Theos Bernard, to purchase the 37-acre Cuesta Linda estate near Santa Barbara from the Gavit family in 1941, to escape the coming world war in Europe. Dedicated to spiritual teachings, she had planned to use it as a retreat for Tibetan monks and renamed it “Tibetland.” But with no monks, due to World War II, and no husband, following the couple’s divorce, the diva changed it a second time to “Lotusland” to honor the Indian lotus growing in one of the property’s ponds.

Over the following 40 years, Walska dedicated her life to transforming the overgrown acreage into an exuberant, more-is-more botanical extravaganza of more than 20 distinct, themed gardens, collaborating with the best landscape architects of the time but insisting on her vision and aesthetic.

“She was bound and determined to do what she wanted to do,” explained Lotusland’s executive director, Rebecca Anderson. “What she wanted to do was create this unparalleled garden, and she had a lot of resistance. She would hire landscape architects, although she considered herself the head gardener and designer, and she wouldn’t follow their advice.”

Anderson recounted a story of Walska working with prominent landscape designer Lockwood de Forest Jr. to help with the area in front of the property’s main house, the most visible building on the property. She wanted to load it up with upright and weeping euphorbia; de Forest countered that she couldn’t put cactus in front of a house because it’s prickly. It’s not welcoming. It’s the opposite of what’s done.

“She, of course, was insistent,” said Anderson. “And later we have a letter from him saying congratulations. That she was right. That’s just so emblematic of her way.”

That area still has the oversized euphorbia as well as a field of golden barrel cactus and white-haired Oreocereus celsianus, or “Old Man of the Andes” cactus.

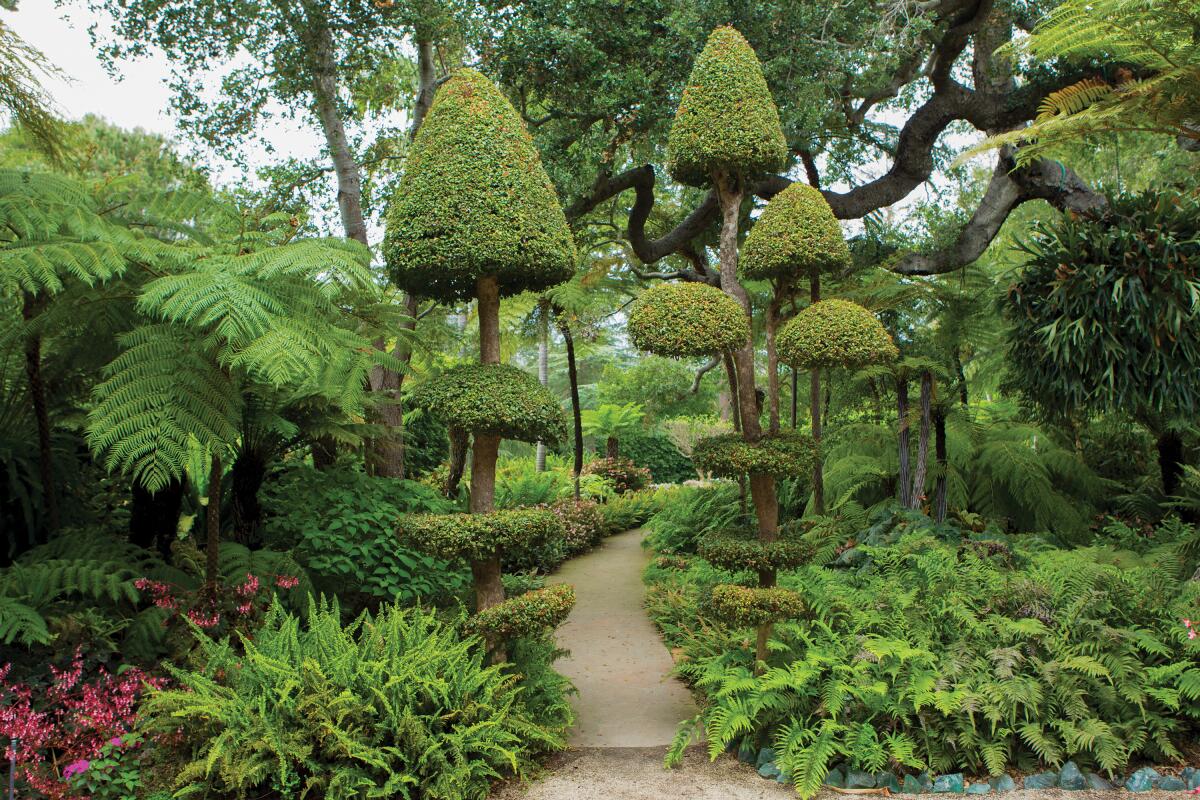

But that’s just the beginning. There’s the Aloe Garden, the Australian Garden, the Cycad Garden. There are gardens dedicated to ferns, to shade palms, and dracaena. The newly renovated Japanese Garden features a central pond with a path and scenic encounters. The Topiary Garden surrounds a working horticultural clock that’s 25 feet in diameter and contains copper zodiac signs. The 26 topiary figures surrounding the clock include various animals and chess pieces. There’s a water stairway of 14 basins that are the end point of a long brick cypress allée, or walkway.

Nan Sterman, a garden expert and designer as well as a journalist, has been to Lotusland multiple times, including the botanical garden’s very first tour just after Walska died in 1984, before it was officially open to the public. One of her favorite spots is the Aloe Garden’s Abalone Pond, with its two cascading fountains of giant clam shells.

“It’s like walking into a dream,” recalled Sterman, who writes a monthly column that appears in The San Diego Union-Tribune. “I was there the first time they opened and then didn’t go back for 20 years. In the time in between, I decided I’d dreamt a lot of what I saw there. It wasn’t until I returned that I realized I didn’t dream it.

“The lotus pond and bathhouse is like you were in a Monet painting. It’s that dreamy,” she added, “that imaginary, that magical feeling. It doesn’t feel like it should be real.”

Paul Mills is Lotusland’s curator of the living collections, which opened for public tours in 1993. While he noted that Lotusland’s mission is to honor Walska’s dream and what she built, and to educate and inspire through the organization’s sustainable horticulture program, he also emphasized the botanic garden’s role in plant conservation — as “sort of life rafts for threatened plants and those that aren’t even threatened yet but may become so in the future.”

One of his personal favorites that he was involved in bringing to Lotusland is the Cactus Garden. The collection of more than 300 species of cactuses was a gift from Walska’s longtime friend Merritt Dunlap. In 2001, Mills helped moved Dunlap’s 530 cactuses from his home in Fallbrook to Lotusland, where they were held in a temporary structure in the backfield until they had the funds to create the garden in 2003.

“I think visitors will quickly realize it’s one of the best displays of cacti you’re going to see anywhere. Dunlap liked the big columnar cacti and it literally has turned into a forest,” Mills said. “One of the great things he had done with his collection and I insisted that we mimic is that he had the collection laid out geographically. So, now as you enter from the main lawn you’re coming up on South America and you go through Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina and Brazil, and then you make it up to North America. We have a little Caribbean section. So, you get to travel through all the great deserts of the Americas.”

There is a lot of inspiration for home gardeners to find at Lotusland. Mills pointed out that all the mass planting — a Walska signature — should also be a good lesson to home gardeners to research a plant before planting it to learn its full potential.

Native San Diegan Barbara Gorder, who now lives with her landscape designer husband in Northern California, found inspiration from the cactus garden.

“The cactuses are very unusual. We’ve been growing a lot of cactus up here in Northern California from a fire safety standpoint. It’s amazing to see how durable and adaptable they are.”

Sterman thinks about natural groupings of plants from wandering through the various Lotusland gardens. She said home gardeners should consider how they’re using color and points to Walska’s drought-tolerant Blue Garden, which is filled with blue fescue, blue hesper palms, blue atlas cedar, and chalk sticks, among many other options.

“Look carefully at the foliage,” Sterman advised. “Her blue garden is all about foliage, not flowers. And it’s multilayers. Palms, giant agave, all the way down to ground level. People are afraid of big plants, but here without the big plants, it would look naked and weird.”

There’s also the nonliving aspects of the gardens home gardeners can enjoy and think about.

“The nonliving collections are equally as significant here,” said Anderson. “Madame Walska used decorative features to adorn the gardens, from tile, to statuary and water features, to the aqua-colored slag glass, which was her signature. She had a gardener who brought her the waste glass from the Arrowhead jugs at the bottling plant. It looks like jewels in the garden when the light shines on it.

“There are a number of different sculpture collections, including wonderful little figurines she brought with her from her chateau near Versailles. They’re in our Theater Garden. We have a collection of 30 ishi-dōrō stone lanterns that span centuries in our Japanese Garden.”

Walska died in 1984 and left Lotusland to the Ganna Walska Lotusland Foundation. By 1992, the foundation established a docent program and received a conditional use permit from Santa Barbara County to open the garden to the public — and the first tour was scheduled in September 1993. Because Lotusland is in a residential neighborhood, access is strictly controlled. Reservations are required, with adult admission costing $50 and admission for children ages 3 to 17 at $25.

Before the pandemic, the only way to see the gardens was on a docent-led tour. But after closing for just five weeks last spring, Lotusland was able to reopen in April 2020 and instituted self-guided tours, using QR codes, volunteers and staff members stationed around the gardens to help tell the story, along with a visitor guide with a map and information about each garden, Anderson said.

In addition, there are plenty of videos on the Lotusland website to orient visitors before they arrive. The site’s videos also have numerous videos for home gardeners on green practices — about compost ecosystems, pollinators (yes, there’s an Insectary Garden), green garden strategies, and managing plants and pests.

Anderson said that Walska’s legacy was that when she had a singular vision, she was tenacious. Her stationery had a monogram: It was malgré tout, which is French for “despite it all.”

“I think that speaks to her approach,” Anderson reflected. “This garden was designed by a very creative, very eccentric, very bold woman who had an agenda, which was to defy convention. And it shows up here in all the best ways.”

Golden is a San Diego freelance writer and blogger.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.