Conspicuously absent from police overhaul plans proffered by the White House, Senate Republicans and House Democrats are moves that would weaken police unions and make it easier to weed out bad cops, a tactic that is touted as key to turning around law enforcement agencies.

“The unions are huge obstacles to police reform,” said Joseph Lukaszek, the police chief in Hillside, Illinois.

He said unions have blocked him from terminating bad cops. “The unions are there to make sure ‘I’ get my pay and benefits, but they are not there to protect people from incompetent police officers,” he said.

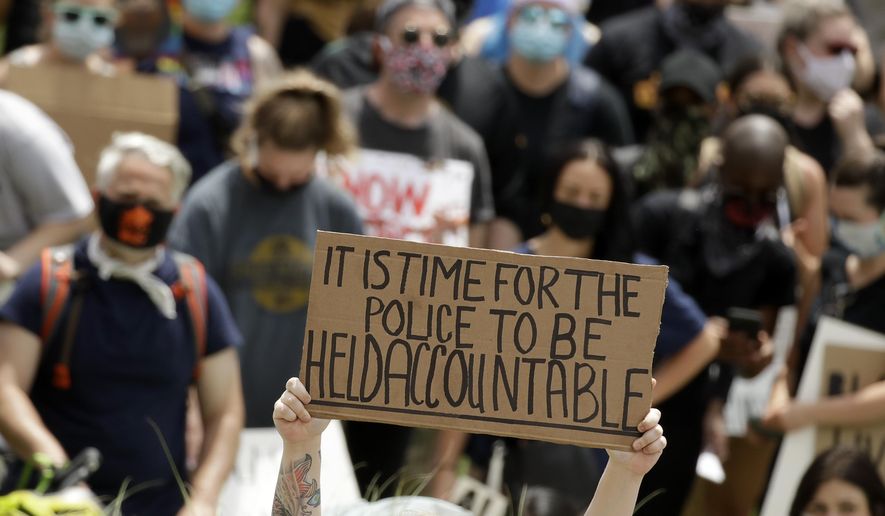

The May 25 death of George Floyd, a black man, in Minneapolis in police custody touched off a wave of protests and prompted lawmakers to rush to overhaul policing policies and mayors to slash police budgets. During Floyd’s arrest, a white officer knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes.

Yet police unions escaped the reformers’ dragnet. None of the proposals took aim at the unions, which have worked for years to keep officers accused of misconduct on the job and police disciplinary records under wraps.

Decades of collective bargaining between the police union and municipalities, critics say, wrested control of departments away from police chiefs and city councils in favor of union leaders.

At least 50 cities and 13 states have union contracts that limit how long an officer can be interrogated, who can interrogate him, and the types of questions asked when an officer is accused of wrongdoing, according to Check the Police, a watchdog group.

Also, 43 cities have contracts with local police unions to erase officer misconduct records, the group said. Added together, the watchdogs say, these measures tie police chiefs’ hands when it comes to disciplining bad cops.

“We have been able to determine those early warning signs and try to get rid of these police officers,” Chief Lukaszek said. “We know who the bad boys are, and those people embarrass us. We don’t want them to have a badge and gun, either.”

Mark Mix, president of the National Right to Work Committee, a think tank that opposes public-sector unions, said erecting roadblocks to disciplinary measures and firings is part of the collective bargaining process.

“There is a complaint against an officer and investigators want to talk to him, but they can’t talk to him for a certain period, and they can’t ask him this or that question, and this topic is off limits,” he said. “It is just like the teachers union where it costs a school district $200,000 before they get to the point where they can fire a teacher.”

Even when officers are terminated, the union fights to return them to the force.

In 2008, Oakland Police Officer Hector Jimenez was fired for killing an unarmed suspect, his second in less than seven months. One of the cases ended with the city paying $650,000 to settle with the victim’s family.

After a two-year battle between the department and the police union, Mr. Jimenez was reinstated with full back pay for the time he was out of work.

The Minneapolis Police Union stood up for the four officers charged with murder or aiding and abetting murder in the death of Floyd. In a letter to members, Lt. Bob Kroll, the union president, said it was “despicable behavior” to criticize the officers.

Among the officers charged, Derek Chauvin, the one who put his knee on Floyd’s neck, had 18 prior complaints filed against him. It is not clear whether the police union helped bail him out of other misconduct accusations.

Few politicians have been willing to directly confront the police union head-on.

Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison, who is handling the prosecution of the officers involved in Floyd’s death, is one of the exceptions.

“We need reform in the area of the police unions to make sure that the chief can actually have disciplinary control over the force,” he said.

When New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, was pressed on taking on the police union, he said “every union argues in the interest in their employees, their workforce.” Mr. Cuomo promised to “listen to all voices,” including those of the unions, on holding police accountable.

“The left is struggling,” Mr. Mix said. “They were the ones that supported the unions, and now they are crying out for police reform and crying that they can’t control their own police force now.”

New York lawmakers have proposed legislation that would allow the public to see disciplinary records for officers.

A key piece of the House Democrats’ police overhaul package would establish a national registry of complaints against officers. But it is not clear from where that information would come and whether records expunged by unions would be included.

Chief Lukaszek proposes going even further.

He said fired officers should pick up legal costs if they lose a bid to regain their jobs. He also called for the reduction in the role of insurance companies in negotiating legal battles.

Insurance companies pressure departments to rehire terminated officers because it is easier than paying hundreds of thousands of dollars in legal fees.

“There are a lot of deals behind the scenes that are not right,” Chief Lukaszek said. “The insurance companies will come back and say someone should be fired, but it will cost $150,000 to defend the case. It is why we are where we are at: because the departments don’t have any power anymore and the insurance companies have taken over. That has happened to me.”

Chief Lukaszek said officers should have the right to sue to regain their jobs but should also face the prospect of paying everyone’s legal bills if they lose. Under the current system, the unions pick up the cost, so an officer terminated for cause has nothing to lose by challenging the termination.

“With the unions behind them, they can lose and still pocket $10,000 out of the deal,” he said. “And believe me, there is always a deal. I have yet to have someone that I’ve gotten rid of walk away without something in their pocket, and it aggravates me to no end.”

Mr. Mix said cities’ public-sector employees shouldn’t have the same bargaining power as private-sector workers, especially in the law enforcement arena where a mistake can be deadly.

“Public-sector unions have this power to elect the people they negotiate with,” he said. “We shouldn’t be having a debate about police reform. We should have a debate forcing the government to stop negotiating with unions.”

Eliminating the union’s power to discipline workers would restore that power to city councils and mayors who are held accountable by voters.

“There are lots of police forces around the country that are not unionized, and the city council is held accountable for bad actors and we hold elected officials accountable,” he said.

• Jeff Mordock can be reached at jmordock@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.