Saturn’s moon Titan is one of the most wonderfully weird worlds in our Solar System. In the way that Earth has a water cycle of rain and evaporation, frigid Titan has a methane cycle and lakes of the liquid stuff. Unfortunately, its atmosphere is thick with smudgy clouds and organic haze, limiting our view.

But while visible light can’t penetrate the atmosphere, other wavelengths have better luck. When the Cassini probe was still hanging out in the Saturnian neighborhood, radar and infrared instruments were used to scan the surface. In a new study published this week, a team led by Rosaly Lopes compiled that data to make a geologic map spanning Titan’s surface.

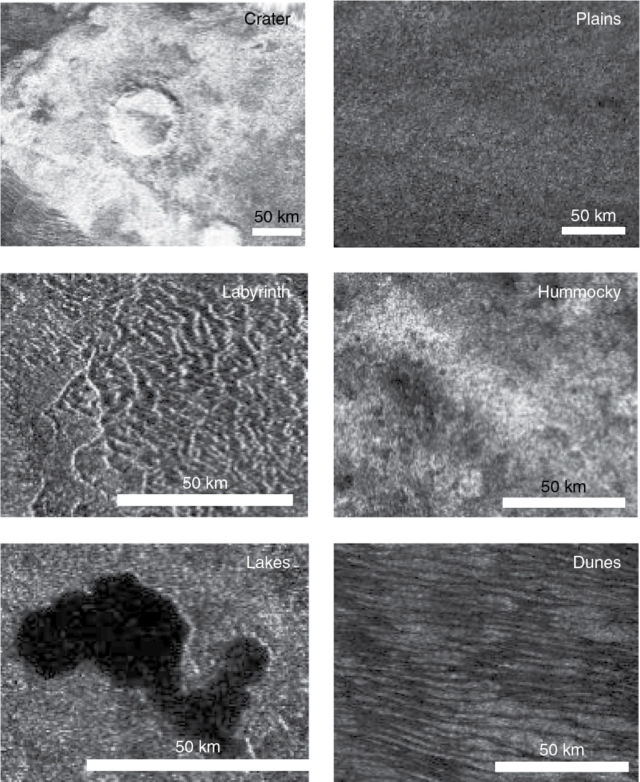

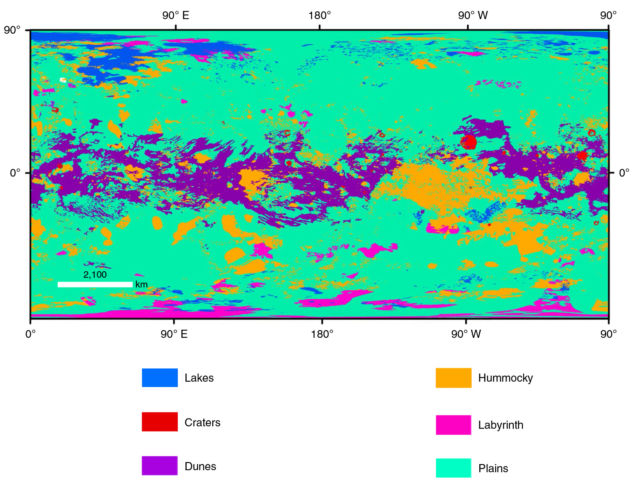

After analyzing the data, the team decided to group the terrain into six types of landscapes: craters, lakes, plains, dunes, hummocky (or mountainous) areas, and something they termed "labyrinth terrains."

The plains are the most widespread, covering about two-thirds of the moon’s surface. They’re remarkably flat, lacking methane river channels—or, indeed, anything else. The way the radar signal bounces back off the surface indicates that it’s probably made of organic stuff that either buried older channels or is porous enough that liquid methane is largely soaking in through it. This material is the result of sunlight-driven reactions high in Titan’s atmosphere, combining methane and nitrogen to produce an organic schmutz that falls to the surface, where it behaves like sediment.

The labyrinth terrains, too, seem to be made of this stuff but are carved up by winding river channels. This isn't very widespread—accounting for only 1.5 percent of Titan’s surface—but appears to have started as high elevation regions eroded by rivers flowing toward lower ground.

The dunes are also composed of the organic sediment, blown by winds into long spaghetti strands similar to linear dunes on Earth. The dunes are spaced by several kilometers and reach around 100 meters tall. They are quite widespread, too, at about 17 percent of Titan’s area.

Finally, the hummocky areas—a geological term roughly synonymous with “lumpy”—represent something different. Mountains up to a couple kilometers in height cover about 14 percent of Titan and appear to be composed of water ice that acts like bedrock in these cold temperatures. The researchers say they likely formed early in Titan’s history, as the moon cooled and contracted—producing wrinkle-like structures on the world’s outer skin.

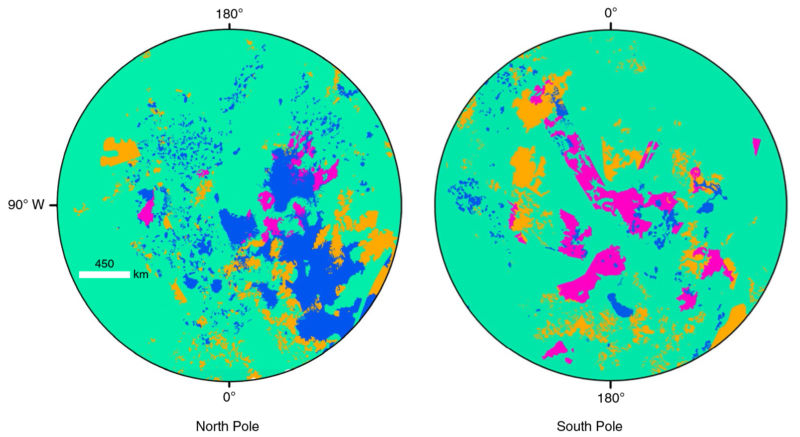

Although the hummocky areas pop up in many places, most of the landscapes aren’t randomly scattered around Titan. They form definite latitudinal patterns that are likely related to climate patterns. The polar regions host the lakes and labyrinth terrains—predominantly lakes in the north and labyrinth in the south, currently. The equatorial region is covered by dunes instead. Between the two is the realm of the plains.

The impact craters that dot Titan can be used to learn a little more about the sequence of events here. While Titan seems to be active enough to erase craters within a few hundred million years, there are enough to get a feel for which landscapes formed on top of other ones (and so more recently). The polar regions are pretty much crater-free, which could mean that impact sites have been buried or eroded away.

On close examination, it seems the hummocky and labyrinth terrains are the oldest, with the plains coming after, and the dunes and lakes being the freshest areas. This makes some sense, as Titan’s poles are the wettest region, while the equator is drier and windy. That means there’s plenty of action in the lakes and dunes, and the plains in the monotonous mid-latitudes are changing more slowly.

The researchers write, “The clear distinction between these units and where they are found on Titan indicates that a variety of processes must be acting on the surface of this moon, controlled by climatic, seasonal, and elevational conditions.” Our eyes may not be able to peer through Titan’s atmospheric privacy fence, but it’s clearly a pretty happening place.

Nature Astronomy, 2019. DOI: 10.1038/s41550-019-0917-6 (About DOIs).

reader comments

64