An 'ah-ha' moment links rare lung disease with cancer and a rogue gene

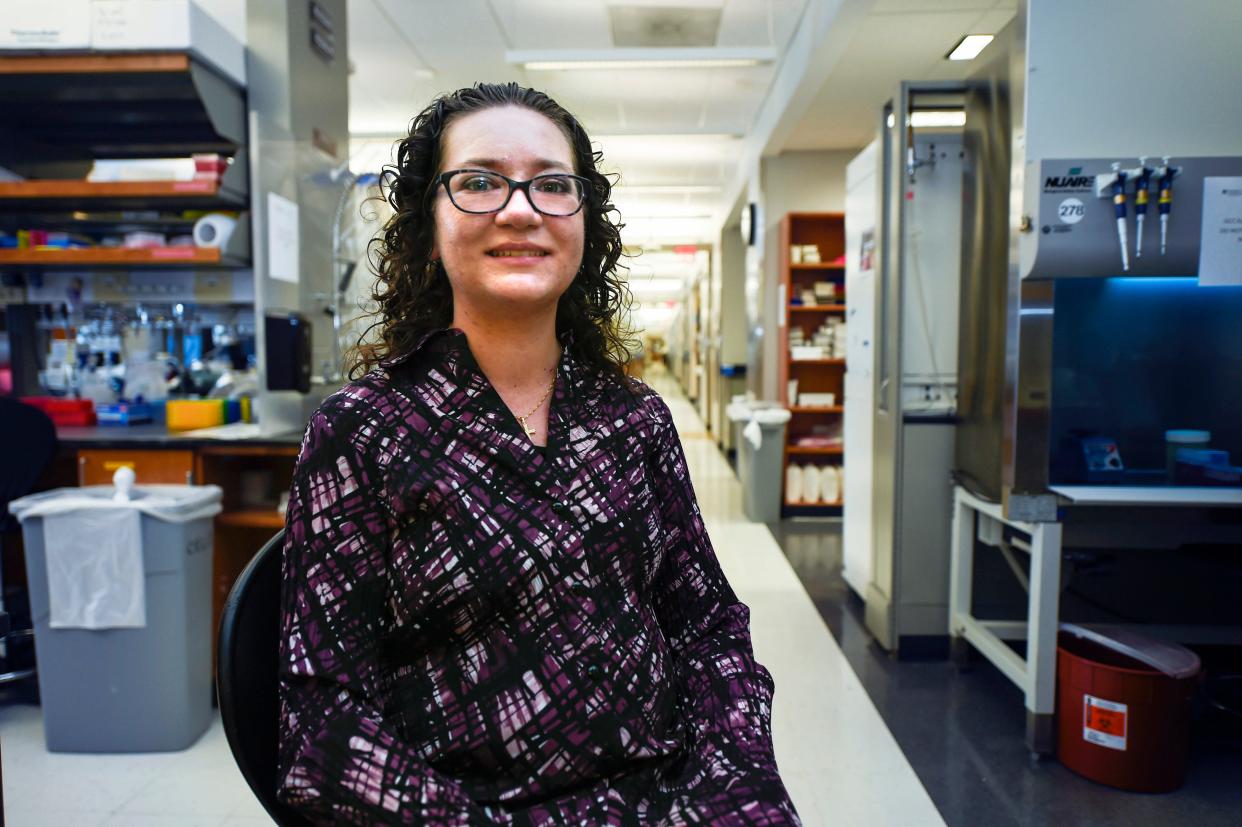

Cancer researcher Caryn Bird, 29, was walking down the hall at Augusta University with her boss when she found she didn't have the breath to carry on a conversation. She stopped, but it didn't get better, even after reaching his office. Her shortness of breath was getting worse and wasn't responding to asthma treatments.

Bird wondered aloud if it was her heart and not her lungs but the other researcher suggested it might be both. Turns out, he was right. It was pulmonary arterial hypertension. And it was almost too late.

"They said it was the most severe case they had ever seen," Bird said. "With the pressures I had, they were surprised I had never passed out before. They were honestly surprised that I was still alive at that point."

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is a rare disease with 500-1,000 new cases diagnosed every year in the U.S. It most often strikes women between the ages of 30-60. It makes arteries in the lungs become thicker and stiffer over time. That increases the pressure in the lungs and makes it harder for the heart to pump blood through it, eventually enlarging and weakening the right ventricle of the heart. Drugs help treat the symptoms, but no cure exists. Once deterioration begins, there's no way to reverse the changes.

But just up the street from Bird's lab in the Georgia Cancer Center research building are other AU researchers who are looking into the fundamental mechanisms of the disease with an eye toward treating or even preventing the damage.

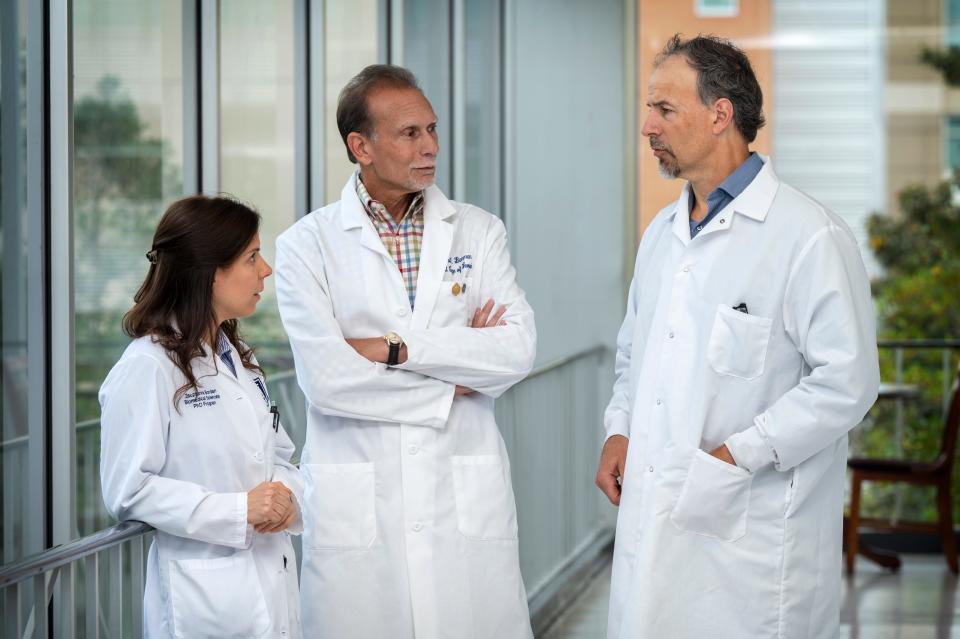

Drs. David Fulton and Scott Barman have a $2.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to pursue their early findings of what might cause those changes. And they appear to share something in common with Bird's field of cancer.

Early on in their work, Fulton and Barman came across a particular gene that became overactive and caused muscle cells in the walls of the pulmonary artery to multiply at an abnormally high level, leading them to thicken and stiffen.

"This gene was one of the most (active), no one had studied it, it kind of caught our attention," Fulton said. "When we looked at the literature... most of the studies there were on cancer."

That's when it clicked for them.

"We thought, "Oh, this could be interesting," Fulton said.

"There’s more and more correlation between (this disease) and cancer being very similar as proliferative diseases," where cells grow out of control and create problems, Barman said.

These muscle cells normally are just involved in contracting and relaxing and have to change over to start multiplying, Fulton said. And that is another link with cancer, Barman said.

"Something turns it on to become a rogue-type cell," he said.

More: 'If you can find the cancer early on': Underused lung cancer screening could save lives

More: Genetic "signature" could point the way to better diagnosis, treatment of lung cancer

They are exploring whether a certain protein will bind to that gene and cause it to become overactive and what particular DNA sequence that protein will bind to, Fulton said. It opens up the possibility of using gene-editing technology such as CRISPR Cas-9 to block or mutate that area to prevent that activation, he said.

That is "21st century stuff," Barman said. "In the end, that is where a lot of this is going" with gene therapy.

In the meantime, cancer research has developed a lot of drugs, and there are two that specifically look to block the activity of these proteins that have been in clinical trials for cancer, Barman and Fulton said.

"We’ve tried those in models of pulmonary hypertension and they are very effective," Fulton said.

One advantage of targeting this gene is "it's not an essential gene," he said. A mouse or rat can be specially bred to not have the gene and it will still develop normally, Fulton said.

"That’s attractive therapeutically because you can block that really high-level proliferation without causing a lot of toxicity,” he said. So aside from the potential drugs, gene therapy "is more of a long-term approach," Fulton said.

"A more targeted therapy is the ultimate goal," Barman said.

In the meantime, Bird is taking a powerful drug that helps relax the blood vessels in her lungs, and she only occasionally has shortness of breath. Her heart rate is in the normal range, and she is looking at completing her PhD in immunotherapy sometime next year or in early 2023.

Her work looks at mechanisms of how cancer evades the immune system, which could help with future immunotherapy. Part of her work relates to a pediatric cancer clinical trial set to get underway next year at AU. In the meantime, she is grateful for the lab work of others, both past and future.

"I’m just really thankful for the research that has gone on to have these different drugs that are available," Bird said. "And for the doctors because I think my diagnosis was pretty quick. I’m very thankful for my faith in Jesus that I have this miracle in my life, that I am able to continue my daily activities on a fairly normal basis and continue my PhD work as well."

This article originally appeared on Augusta Chronicle: Rare lung disease prompts AU to research into causes and cures