Pounded by rain bombs from above and rising seas below, Charleston is among the most vulnerable cities in the South to a rapidly warming planet.

City officials estimate it may take $2 billion or more in public money to fortify Charleston against these threats — costs rooted in the rise of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Yet, amid these looming perils and costs, the city government itself has taken relatively modest steps to reduce its own carbon footprint in recent years, a Post and Courier investigation found.

- Nearly all of the city’s roughly 1,200 cars and trucks still run on gas and diesel instead of cleaner fuels or electricity.

- The city has no solar panels on its buildings.

- Its landscaping tools spew a toxic brew of hydrocarbons.

- It hasn’t formally challenged Dominion Energy to supply more renewable electricity, a lever other cities have used.

The city has reduced some of its carbon dioxide emissions, thanks to an 18-year-old contract to upgrade equipment and install more efficient lighting.

And city staff talk with enthusiasm about emission-reduction projects they hope to do in coming years.

But political and economic hurdles have torched previous reduction plans. And it remains unclear how effective the city’s greenhouse gas cuts have been. The city hasn’t measured its carbon footprint since 2010.

On paper, the city has ambitious goals. In 2017, Charleston Mayor John Tecklenburg joined other U.S. mayors in a pledge to cut 30 percent of the city’s carbon dioxide emissions by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.

To reach those numbers, citizens, businesses, government and power companies all must reduce their carbon emissions.

Yet, Charleston's experience raises questions — ones many other coastal municipalities face: Should they lead by example, even if reducing emissions costs taxpayers in the short run? And, will cutting emissions siphon money from projects to protect the city?

Jonathan Cattle pushes his car to higher ground along Hagood Avenue in Charleston during December 2019 flooding. File/Andrew J. Whitaker/Staff

An incremental assault

The largest city in South Carolina’s Lowcountry, Charleston is on the front lines of climate change. Driving this change are rapid rises in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

These gases trap heat and allow the atmosphere to hold more moisture, generating more intense rainstorms. Much of the heat also goes into the ocean, melting polar ice caps. Higher heat causes seawater to expand. All of this contributes to rising sea levels, evidence you can see in Charleston Harbor.

Since the 1920s, sea levels here rose at a rate of about an inch every decade. Now the pace is roughly an inch every two years.

A few inches may not seem like much, but the cumulative impact adds up: edges of marshes fray; tidal currents eat into the banks of beaches and inlets; higher tides push stormwater into streets. During the 1960s, Charleston saw a handful of nuisance tidal floods a year. In recent years, the city averaged 40 or more, with 2019 setting a record 89 — a coastal flood event every four days on average.

Amid these impacts, the city’s record on climate change issues has moved like those tides, with highs and lows.

One high water mark came in 2007, when Charleston formed a Green Committee to craft a local climate change plan. Then-Mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr., said: “In the global effort to protect our environment, the first steps start at home.” About 800 volunteers participated and they met more than 140 times. The committee made strong recommendations to reduce CO2 emissions.

Then, instead of adopting the committee’s “Green Plan,” city council merely “received” the report — accepted it without approval, effectively defanging it. In 2010, the city adopted its Century V plan, its comprehensive plan for the future. That report didn't mention the words "sea rise."

Now, after flooding tropical storms marched through South Carolina five years in a row, Charleston leaders are moving more aggressively to bolster the city’s defenses.

Climate-related projects include a $64 million initiative to raise and rebuild a 4,800-foot seawall for the Low Battery in downtown Charleston's historic district, an effort to buy frequently flooded homes in suburban West Ashley and $200 million worth of work to reduce flooding near the Septima Clark Expressway. Hundreds of millions of dollars more will be needed to protect other parts of the city.

Amid these expensive projects, the city’s efforts to reduce its greenhouse gases have barely gathered steam.

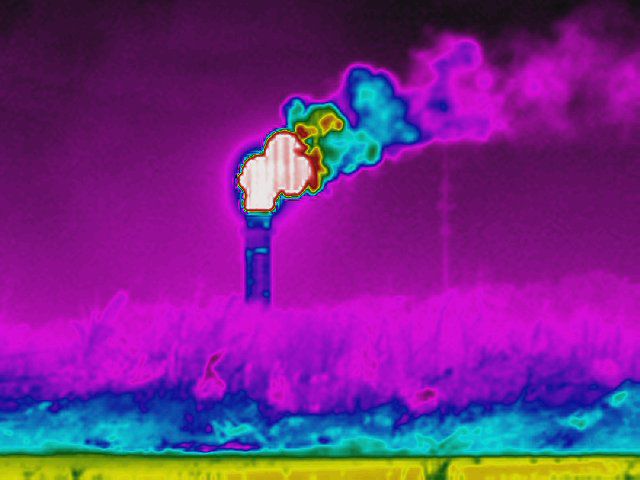

In 2016, as part of The Post and Courier's "Every Other Breath" series, the newspaper obtained a one-of-a-kind thermal imaging camera from FLIR to document everyday sources of invisible CO2 emissions. This shows CO2 emissions from a sedan's tailpipe. File/Tony Bartelme/Staff

Gas guzzling

Consider its fleet: All told, the city has 1,174 cars and trucks, including 685 in the police department and 96 in the fire department, city officials said.

Of those vehicles, six are hybrids — or half of 1 percent. All were bought more than eight years ago. The city has no electric cars.

As a result, the city burns an average of 840,000 gallons of gas and diesel fuel a year, roughly equivalent to 93 tanker trucks.

Every gallon of gas produces about 20 pounds of CO2, making the city’s vehicles responsible for as much as 7,700 tons of CO2 emissions. That’s equivalent to the emissions generated by 900 homes in a year.

At just about 5,000, the number of electric vehicles on South Carolina's roads today is tiny compared to their gasoline-fueled cousins. But utilities here know that will soon change, and they are already preparing.

The city’s fleet managers are gathering data on costs and benefits of moving toward electric vehicles, said Tracy McKee, the city’s chief innovation officer.

“We’re on the cusp of getting some metrics to convert our fleet.” But, she added, “the game plan is still in flux.”

Tecklenburg added: “We’re consumers like anyone else, and we’re mindful of spending people’s tax dollars. There’s been a premium to switch to electrical vehicles.”

City of Charleston crew mow in Cannon Park, as shown through the lens of a camera that can identify carbon dioxide emissions. File/Tony Bartelme/Staff

Leaf blowers

Gallon-per-gallon, gas-powered landscaping tools are even bigger polluters than vehicles. In a half hour, a typical leaf blower cranks out hydrocarbon emissions comparable to driving a Ford pickup truck across the country, Edmunds, the car information company, found in a test.

City of Charleston crews use 35 gas-powered backpack leaf blowers and 45 trimmers, city officials said. Most have 2-stroke engines, the worst emissions offenders. That might change.

Jason Kronsberg, director of parks and management, said his department has been studying for two years how to switch to electric tools.

Crews have tested two companies’ products, and they worked fairly well.

“They’re quieter and really efficient,” he said. “We’ve been waiting for the technology to catch up, and we think it’s almost there.”

Going electric is nothing new. California regulators are mulling a statewide plan to phase out gasoline-powered leaf blowers and lawn mowers. At least 90 cities across the country have some kind of ban already.

But Kronsberg said a switch still requires rewiring the way crews do their jobs. Instead of carrying petroleum fuel, crews will need to find ways to keep batteries charged.

His department also may build a solar-powered trailer to recharge and store batteries, he said, adding that he hopes to outfit a crew with electric tools this year as a pilot project.

Aside from vehicles and maintenance equipment, the city has other tools to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. These tools involve persuasion, and the city has only vague plans about using them.

SCE&G's Hagood Station on peninsular Charleston pumps out CO2 from its stack, but this gas can only be seen with a special thermal imaging camera made by FLIR. File/Staff

Leverage

With the exception of its vehicles, the city’s carbon footprint is largely dependent on how utilities produce electricity. Power companies that crank out electricity with coal are among the biggest contributors to the rise in CO2 levels globally.

Dominion Energy is the city’s main power provider, and it’s expected this year to ask state regulators for a rate hike. This could give the city one of its best chances to prod Dominion toward providing cleaner electricity, conservationists say.

“Their future energy mix is being determined now,” said Eddy Moore, energy and climate program director for the Coastal Conservation League.

The process is highly technical. Dominion must file a detailed “Integrated Resource Plan” with the S.C. Public Service Commission, the state regulators who set our rates. The Integrated Resource Plan spells out how Dominion will generate electricity in the next 15 years.

Facing dire threats from a changing climate, Southern states are taking baby steps to protect their lands and reduce their carbon dioxide footprints.

As part of this process, interested parties, including cities, can intervene and formally challenge the utility's plans. In North Carolina, the city of Asheville, Buncombe County and conservation groups intervened in a Duke Power rate case, an effort that led to the shelving of a controversial natural gas plant.

But when asked whether Charleston had plans to intervene in a Dominion rate hike case, city leaders seemed unsure about the process and vague about its potential.

“It’s certainly something we’ll be looking at going forward,” said Susan Herdina, city attorney.

“We’re discussing it. We’re just trying to understand the whole process,” said Katie McKain, the city’s new director of sustainability.

Tecklenburg said he was happy to be an advocate for cleaner power, but had not had any substantive conversations about the city’s role in intervening in a rate case.

“It hasn’t been in our wheelhouse.”

***

In addition to serving as an intervenor, the city has another lever with Dominion: its lucrative franchise fee agreement.

Every customer pays Dominion a 3 percent fee for the power they use. Dominion then forwards this money to the city. In exchange, Dominion gets rights to provide power to the city’s residents and businesses. Last year, the city raked in $12 million from this fee.

The city inked its current franchise fee agreement in 1996, a 30-year deal. Though more than six years are left, negotiations on a new one are set to begin as early as this year, said McKain, the sustainability director. In 2017, Minneapolis raised its franchise fee half a percent to pay for climate programs.

McKain acknowledged that the city of Charleston’s franchise agreement was “antiquated” and that “we’re constantly working with the utilities and constantly encouraging them to do more renewable power generation.”

When asked for specific documentation of requests, city officials couldn’t cite any.

Not many local governments and school districts in South Carolina have embraced solar power, but several that have taken the plunge couldn't be happier.

Solar hitch?

Solar panels were a relatively rare sight in South Carolina five years ago. Since then, the solar industry here has grown exponentially. The state now has enough solar panels to power 122,000 homes, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association.

A few governments have installed solar panels. Saluda was the first in the state to install rooftop panels. Edgefield School District installed solar panels at a single elementary school, a move expected to save the district $900,000 over 10 years.

And Beaufort put panels on five of its main buildings during the past three years. The panels, along with other energy efficiency work, helped cut that city’s power bills by 67 percent, or about $125,000 a year, Beaufort officials say.

“We’re hoping that we set an example,” Beaufort Mayor Billy Keyserling said.

Solar in the city of Charleston?

So far, the city has no panels on any of its buildings.

The historical nature of some of the city’s buildings make solar panels a challenge, said Jack O’Toole, the city’s spokesman. He said the city asked its building management consultant, Johnson Controls, to look at solar power a few years ago, but was told solar panels wouldn’t be cost effective. Johnson Controls didn’t submit a written report on the issue, O’Toole said.

City officials cite another possible hurdle: its 1996 franchise agreement with Dominion. The agreement says that, should the city “at any time construct, purchase, lease, acquire, own, hold or operate an electric distribution system,” the city would forfeit its lucrative franchise fee revenue.

Herdina, the city attorney, said she’s not sure whether the language throws a wrench into the idea of installing solar panels, but it’s a “pretty daunting provision.”

Better buildings

The city’s biggest strides came amid a long-term push to make its buildings more energy efficient.

In 2001, the city hired Johnson Controls to coordinate its energy efficiency work. The consultant helped the city replace older heating and air conditioning equipment, install programmable thermostats, install high-efficiency LED lights and even found ways to make the city’s vending machines more energy efficient.

All told, this work saved the city nearly $17 million since 2001, city officials said. It reduced the city’s energy consumption by nearly half during that time.

The city said that power reduction corresponds to a decrease of about 137,000 tons of CO2 over the past 18 years. By one measure, that’s equivalent to taking 29,000 gas-powered cars off the road for a year.

The city also is in the midst of a three-year program to install more LED lights and upgrade its heating and air-conditioning systems, including equipment that runs on more environmentally friendly refrigerants.

That work is expected to save an additional $12.3 million over the next 15 years and a reduction of 45,000 tons of CO2 that otherwise would have been produced.

“It may come as a surprise to most folks that a good bit of energy consumption is through buildings, not cars and transportation,” Tecklenburg said. “As a steward of the public’s tax dollars, I feel comfortable about the direction we’re heading.”

Rain and high tides more frequently flood Charleston's streets. File/Grace Beahm Alford/Staff

Lead by example?

In 2002, the city measured its citywide carbon footprint, estimating that its residents, businesses and government cranked out 2.1 million tons of CO2.

They measured again in 2006 and again in 2010. By then, emissions had grown 12 percent, to 2.35 million tons. That increase of 250,000 tons is equivalent to emissions from 53,000 cars.

The Green Plan called for the city to get 15 percent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2020. It set aggressive schedules for the city to make both private and government buildings more efficient. Had the city followed its original Green Plan goals, C02 emissions today would be fewer than 2 million tons and going down.

But the city doesn’t know the size of its current carbon footprint. It hasn’t measured it since 2010 and is only now gathering new data.

McKain, the city’s new resilience director, said the city hopes to have a new tally this year.

“You’ve got to look at what we’ve been dealing with,” Tecklenburg added, referring to the flooding-related projects the city has been working on. “We’re on the frontline of the impacts of sea rise and we’ve been devoting a lot of energy to that being on that frontline. That doesn’t mean we haven’t mindful about the causes of these impacts.”

Money spent on reducing carbon dioxide emissions might be better spent on flooding, he said.

“So if it would cost $2 million to buy electric vehicles versus $2 million to put in a drainage project — when we already don’t have enough money — then what are you going to do?”

But money spent on carbon reductions doesn't always siphon money away from other city needs, said Norman Levine, a geology professor at the College of Charleston who has researched carbon budgets.

He cited how it may cost money up front to improve building efficiency or install solar panels, but cities often save money in the long run.

"It isn't a do one thing or the other situation. You can do both."

Charleston isn't the only coastal municipality with a mixed record. City of Myrtle Beach spokesman Mark Kruea could not come up with existing examples of solar panels on city buildings, hybrid or electric city vehicles, or large-scale efficiency measures in public facilities.

Farther afield, a global survey of 66 cities showed only one-fifth had strong clean energy policies, according to the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, a Washington, D.C., nonprofit.

Conservation groups say that municipalities can play an outsize role in reducing a community's overall carbon emissions. A city's vehicles and tools and buildings can be more visible than those used by residents and businesses, giving their use symbolic power.

“Leading by example is very important for municipal governments,” said Christine von Kolnitz, chair of the Charleston-based Robert Lunz Group Sierra Club. She credited Tecklenburg for making “great strides in turning the ship.”

But she and other conservationists said the city should do more to attack the causes of a rapidly warming planet.

"A city like Charleston that needs billions of dollars to cope with the symptoms of climate change needs to address their underlying cause," said Blan Holman, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center in Charleston. "In addition to all of the great food here, the Holy City needs a carbon diet."

Mikaela Porter of The Post and Courier contributed to this report.

Editor's note: This story was produced as part of a regional collaboration of news organizations and Inside Climate News.

The Post and Courier obtained a rare camera that makes C02 visible to the naked eye. The results give us a new way of looking at humanity's impact on the climate.