Personality

We Know Animals Have Personalities. Does That Make Them Persons?

Are there moral implications to the idea that animals have personalities?

Posted June 21, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

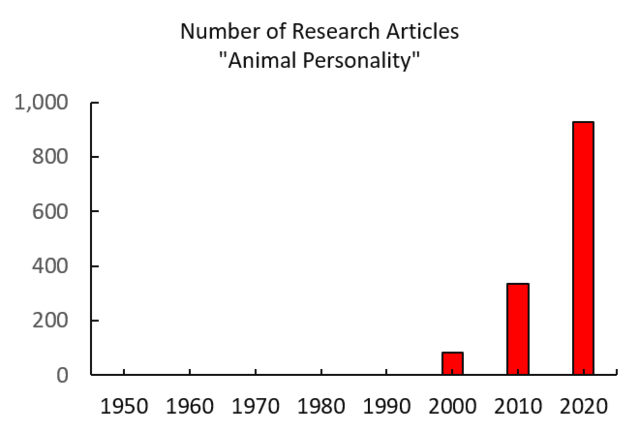

- Research on animal personalities has exploded over the past two decades, from zero in 1990 to over 900 in 2020.

- Personality differences exist in species ranging from insects to great apes.

- There are excellent arguments for granting basic rights to some nonhuman species, but having a personality is not one of them.

For an article I was writing on human-cat relationships, I recently interviewed my friend Beth about her feline companions—a pair of 3-year-old brothers named Finn and Chatsworth. As soon as I walked in the door, Finn ran up to me, purred, and rubbed against my leg. When I reached down and scratched behind his ears, he looked me in the eyes and purred some more. Then he followed us onto the porch and plopped into the chair next to Beth. She told me he spends most of his day following her around. He is with her when she cooks dinner in the evening and in the morning when she’s reading the paper. At night, he sleeps in her bed. Finn likes her husband Richard OK, but he loves Beth.

“Where’s Chatsworth?” I asked her.

“Chat hides in the basement whenever a stranger comes in,” she said. “He’s not as comfortable as Finn in the human world. He never has been.”

Unlike Finn, Chat spends most of his day outside making life difficult for the furry and feathered creatures in the neighborhood. Sometimes he brings home a chipmunk or a bird—even an occasional small snake. And once, to Beth’s horror, a rabbit. Beth feels guilty about living with a serial killer. She only reluctantly began to let Finn outside when it became obvious that he was miserable—glued to the living room window watching the birds. She concluded it was cruel to confine him to the big cage she calls her house.

To me, Finn and Chat look almost identical. But whatever the cause—genes, environment, or the vagaries of random chance—their personalities are in many ways polar opposites. Finn is calm. He likes people and begs for attention. He goes outside for an hour in the morning but never leaves Beth’s yard. His brother, on the other hand, is a born killer whose territory includes the whole neighborhood. Nervous around strangers, Chat likes to hang out—draped like a leopard in the Serengeti—on the limb of a tree.

The Snake Personality Studies

Every pet owner knows that animals have unique personalities. Until recently, however, the topic was not taken seriously by researchers. I became interested in the personalities of animals back in the 1980s when I was studying snake behavior in Gordon Burghardt’s Reptile Ethology Lab at the University of Tennessee. I noticed that some newborn garter snakes—even those from the same litters—were feisty and aggressive while others were calm, even placid. I developed a method to measure these individual differences. It involved a standardized procedure in which I would count the number of times a snake would strike or bite my index finger during a three-minute trial.

Over the next couple of years, Bonnie Bowers, Gordon Burghardt, and I published nearly a dozen papers using this technique to explore why some snakes are foul-tempered and aggressive while others are gentle. Bonnie and I did most of the testing, and in our studies, we were bitten thousands of times by baby snakes. Indeed, it is nearly certain that we have been bitten more times by snakes than anyone else in human history. (However, their bites were painless and never broke the skin of our fingers.)

The studies were productive. We found, for example, that:

- Closely related species differed in their temperaments. Babies of a Mexican garter snake species (Thamnophis melanogaster) would bite our fingers dozens of times in a single trial, while it was nearly impossible to provoke a Butler’s garter snake (Thamnophis butleri) to attack our finger.

- Snakes with more aggressive moms tended to have more aggressive babies.

- Snake temperaments were stable over time. Babies that were aggressive when they were one day old were also aggressive months later and vice versa for their placid brethren.

- Like human personalities, individual differences in the temperaments of snakes are affected by both genes and experience. In Eastern garter snakes, for example, about 40% of differences in the tendency of snakes to attack our hands were due to genes.

Gordon, Bonnie, and I always thought of these experiments as studies of snake personalities. In our publications, however, we never mentioned the term “personality.” At the time, the idea that animals had personalities was taboo among animal behavior researchers. For example, according to Google Scholar, there were hardly any research papers published before 2000 on the topic. But over the past two decades, sparked, in part, by a series of papers by University of Texas psychologist Sam Gosling, the tides changed. As you can see from this graph, the number of research papers on animal personality jumped from zero in 1990 to over 900 in 2020.

The study of animal personalities is now a flourishing field of research. Personality differences have been documented in species ranging from chimpanzees and dogs to zebrafish and spiders. (For an excellent overview, see the 2017 book, Personality in Nonhuman Animals). An interesting aspect of animal personalities is that the well-known Big Five personality factors (Openness to New Experiences, Conscientiousness, Extroversion-Introversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism/Anxiety) that characterize human personalities also apply to some other species, for instance, dogs, chimpanzees, and orcas. (Our snake personality test tapped into a reptilian version of the “agreeableness factor.”)

“Having a Personality” Is Not the Same as “Being a Person”

But having a personality is different from being a person. The term “personality” generally refers to individual differences in behaviors that are consistent over time and that set individuals apart. But what does it mean to be “a person?”

To most people, the meaning of the term “person” is simple—a person is an individual human being. Legally, however, things get sticky when trying to decide who or what is entitled to “personhood.” But the idea is important. The abortion debate, for example, hinges on whether a fetus is a person. Animal rights legal scholars such as Steven Wise argues that creatures such great apes and elephants are persons. And a 2013 op-ed in The New York Times by canine researcher Gregory Bern had the headline, “Dogs Are People Too.” In the infamous 2010 Citizen-United case, the United States Supreme Court ruled that in matters of freedom of speech, corporations are persons. And courts have ruled rivers can be considered persons under the law in New Zealand and India.

Personality, Persons, and the Moral Status of Animals

A reasonable case can be made for the notion that some non-human species should be considered persons under the law. For instance, I would much prefer that the Supreme Court had ruled that circus elephants or captive orcas were persons than, say, a corporation like Purdue Pharmaceuticals.

Animal protectionists sometimes use the fact that animals have personalities to make the case for animal rights. For example, in a lawsuit brought by the Nonhuman Rights Project to establish personhood for two captive chimpanzees, the primatologist James King stressed the fact that chimpanzees had personalities. And Barbara King’s book on the mistreatment of industrially raised food animals is titled Personalities on the Plate.

I am not convinced that the existence of animal personalities is relevant to the argument for animal rights. It seems that nearly every species of animal exhibits the types of individual differences in their behaviors that fall into the broad category of “personality” For example, a review paper titled “Studying Personality Variation In Invertebrates” describes personalities in a slew of species such as ants, aphids, and sea anemones that, in my view, warrant only marginal individual moral concern.

The second reason is that while some characteristics confer moral status, others do not. Philosophers differ on which capacities are morally relevant. The utilitarian ethicist Peter Singer, for example, argues that creatures who can suffer and experience pain warrant moral consideration. But the late Tom Regan restricted moral status to beings who are “the subjects of a life”—that is, creatures that possess higher characteristics such as consciousness, beliefs, desires, memories, intentions, and a sense of the future. But from a philosophical perspective, simply being unique, does not carry much moral weight.

The Bottom Line

When it comes to moral standing, having a “personality” and being “a person” are not the same thing. Creatures from bugs to elephants exhibit the stable individual differences comparative psychologists refer to as “personality.” And under the law, entities from rivers to corporations and human embryos have been considered legal persons despite the fact that they do not have personalities.

There are lots of reasons we should be concerned about the treatment of animals, but having individual personalities is not one of them.

Facebook/LinkedIn image: Rachel Griffith/Shutterstock

References

Waters, R. M., Bowers, B. B., & Burghardt, G. M. (2017). Personality and individuality in reptile behavior. In Personality in nonhuman animals (pp. 153-184). Springer, Cham.

Gosling, S. D. (2001). From mice to men: what can we learn about personality from animal research?. Psychological bulletin, 127(1), 45.