It was going on 9 p.m. when Jim DaRin crashed into a light fixture 15 feet in the air and split his head on a conveyor belt at the Miller brewing plant near Fulton.

An explosion paralyzed DaRin below the collarbone, leaving him with minimal use of his hands and rendering him a quadriplegic at age 20, three months before his third season with the Syracuse University football team.

Told he may be institutionalized for life, his mother kneeled down and whispered in his ear: You still have your mind, Jimbo, you still have your mind. You’ll be thankful for that.

Without his mind, he wouldn’t be hurling himself 44 years later, too stubborn to swap in an automatic chair when he can still get around himself.

Without his mind, he couldn’t prove his life didn’t end June 24, 1977, the night he went to work and got shredded by an exploding beer keg.

He was awarded a settlement totaling $6.2 million, paid out over 50 years, and he built a house in Manlius, wanting to be independent.

He’d drag race, snowmobile and hunt, like everyone else. He’d hop on the tractor and mow his lawn, like everyone else.

He’d get elected president of the Syracuse Football Club, a fundraising and alumni group, despite getting run off by the university a few years after the accident and never graduating.

The all-state football and lacrosse star from Jamesville could have wilted away, bitter till the end. At 63, DaRin measures his life by what the accident has given him.

There’s the friendship with Roy Simmons Jr., the legendary lacrosse coach and artist who restored his social life without making it a pity party.

There’s the day he sat in a doctor’s office in Cooperstown, New York, with tears in his eyes: “I don’t want to die. I have the greatest life in the world.”

There’s a new purpose, mentoring young men shaken by paralysis, fearful their dreams shattered in a car crash or motorcycle accident.

He has the love of his life and twin daughters who adore him. He’s got loyal friends and a rock-solid faith. He has what men who aren’t in wheelchairs strive for their entire lives, and he doesn’t take any of it for granted.

After the accident, he kept a thought while laid up in bed, gathering truth as he stared out his hospital window watching workers bustling on the streets below at sunrise.

Each day is a gift.

Don’t waste it.

‘Jim, don’t talk like that’

When a summer job lifting kegs, twisting pressure lines and hoisting aluminum onto the assembly belt went unfilled by SU football players, Roy Simmons Jr. had someone in mind when he walked up to coach Frank Maloney’s secretary in the football office.

“I got one,” Simmons told her. “Don’t tell Frank. I’ll fill that job with a lacrosse player.”

DaRin was a farm boy at heart, stacking logs with precision to dry into seasoned firewood, carrying stones for his father to load on top of another for a wall that’s still standing on Seneca Turnpike. DaRin mowed the lawn of the cemetery Dad cared for, hand-clipping the blades around each headstone. In this family, the work wasn’t finished unless done right.

Football paved his path to college, but DaRin’s first love was ice hockey. He trudged through the snow to the frozen pond way out in the yard with some two-by-fours and chicken wire and fastened a goal. He can still close his eyes and feel the freedom of skating with a stick and a puck.

Lacrosse was no different.

Simmons Jr., and his father, recruited DaRin out of Jamesville-DeWitt High School, watched this 6-foot-2, 220-pound center middie run up and down the field and arrived at a stunning conclusion.

“He was the closest thing to Jim Brown,” Simmons said. “He had the size. He had the skill. He had it all.”

DaRin approached Simmons about playing lacrosse. When word reached the football staff, the coaches put an end to it.

After the accident, Maloney visited him in the hospital every day, sometimes twice.

Simmons showed up, too, to talk with the player he never got to coach.

“I guess I’m all through with athletics,” DaRin told him, “probably never walk again.”

“Jim, don’t talk like that. You’re going to be all right.”

After rehab, Simmons brought DaRin into the lacrosse program to run the fundraising club, letting DaRin know he was OK the way he was, that having a handicap shouldn’t preclude him from anything.

DaRin flew with the team on road trips and was gifted a championship ring in 1983 when SU won its first national title.

“I have all these athletes that run like the wind, and I got Jim, and he could run faster and better than any of them,” Simmons said. “But no one knew that.”

They hosted parties at DaRin’s house; the mural with the white-winged dove in the pool house pays homage to their shared love of Stevie Nicks.

DaRin often drove around the corner to Simmons’ house, honked the horn and waited for his friend to come outside and talk. If Simmons wasn’t home, he’d leave a bottle of bourbon in the driveway, like a calling card. They never talked about the accident.

All this time later, the coach carries a bit of remorse.

“I always felt bad about that,” Simmons said. “I was instrumental in getting him that job.”

An explosion nearly killed him

Janet and Nick Raasch got the phone call late Friday night: Jim was in an accident.

They drove in the rain to the hospital in Fulton. DaRin, too big for a stretcher, arrived on a door frame. DaRin was talking and coherent and still wore his boots when his sister and her husband arrived.

A powerful blast from a small valve of a faulty keg spared his heart but pierced his throat. Metal shards severed his vocal cord and ripped through his spinal column before exiting his 22-inch neck. It took 250 stitches to sew a gash the length of his head. The ice chips they fed him dripped from his neck.

Nick was studying medicine at the time and noticed DaRin’s still body. He called Dr. Robert King, a family friend and the chief neurosurgeon at Upstate Medical Center, who decided DaRin needed to be in Syracuse: Bring him in right away.

They sandbagged him to keep him immobilized. When he arrived at the emergency room, King described his condition as a war injury. He phoned a throat doctor, and they performed a pair of operations that day on the esophagus and spinal cord. When they finished, they put DaRin on a Stryker frame, and he spent several months in the neural intensive care unit.

“Somebody who wasn’t that big and strong wouldn’t have survived,” Nick Raasch said.

At first, DaRin communicated by sticking out his tongue and blinking his eyes. A metal crown was bolted to his temples, leaving a trail of blood trickling down each side of his head. Nurses spun him over to keep his blood circulating, eyes to the sky, eyes to the floor, as if he was a pig on a barbeque spit.

“Barbaric,” his sister called it, “but it was a necessity.”

Toward the end of a four-month hospital stay, after more than 10 operations on his esophagus to patch a hole that was like trying to sew butter, DaRin’s sister spoon-fed him sherbet.

Down 125 pounds on a diet of glycerin swabs, DaRin smiled as he felt the intense flavor and coolness running down his throat. His sister cried as pink dots oozed out of his neck.

“Why didn’t this happen to me?” she asked him.

“Don’t you ever say that!” DaRin shot back. “You couldn’t have survived this, but God knew I could.”

A promise to a friend: You still go

DaRin sat face up in bed, head still, and heard the footsteps coming down the hallway, saw the silhouette grow larger out of the corner of his eye until John Welch, a high school teammate weakened by cancer, swigged a sip of water to compose himself and stepped through the door.

They made a pact to meet up at the Tecumseh Club, a place where $2 covered eight beers, shoes stuck to the floor and fists busted through glass windows so often the owners installed plastic. They imagined returning to their favorite bar and raising a glass, best friends from Jamesville-DeWitt High School toasting two lives damaged but unbroken.

Later that fall, after the chemo and radiation burned out his throat, Welch scribbled three words on a sheet of yellow legal pad paper and handed it to DaRin.

You still go

Welch died that night, Oct. 7, 1977.

“It’s something I never talked about with anybody,” DaRin said. “That’s something really deep in my heart. I think I devoted a lot of my life trying to always try to live the most every day because of that. He lost his. We wanted to get out together, and it was just me.”

In rehab, wailing, then peace

A week after Welch handed him the note, DaRin returned to Archbold Stadium for the Penn State game. He hid in the press box because he couldn’t bear watching from the field when he couldn’t even hold a football.

Two years earlier he felt like he could leap over the goalposts, J-D’s two-way lineman and member of The Post-Standard’s “Dream Team,” one of the first freshmen to suit up for the varsity, doing as he wrote in his high school yearbook: playing big-time football.

The next summer he strapped weights to his ankles and chest, then pumped his legs up the stone steps at Clark’s Reservation to rehab a knee injury.

And now? In a few weeks he’d be up near Boston learning bladder care and how to dress himself with his teeth. Those hands that once gripped and threw down linemen, that tossed 50-pound hay bales on the farm as a boy, couldn’t handle a Dixie cup off the rolling tray.

Distraught, he wheeled to the chapel inside the rehab center and looked up at the cross for 10 minutes: Was I still a man?

He burst into tears and screamed, overcome by the realization he would never stand and walk again. Then, just as quick, it was over. He made his peace with God, convinced there was a reason he was still alive.

Back home, a feeling of exclusion

After months of rehab, he entered through the garage and wheeled into the kitchen.

“I’m all done with therapy,” he told his dad.

“This is it? You’re not walking?”

Etilo DaRin was a first-generation Italian-American who fought in the Pacific, a talented mason who worked at the prison and quarry in Jamesville. DaRin’s mother, Virginia, worked at the library on SU’s campus and devoured the crosswords in The Post-Standard and Herald-Journal. DaRin, one of eight kids, six of them boys, inherited Dad’s work ethic and Mom’s gentle touch.

His father prepared for this day by building ramps around the house and widening doorways, yet he struggled with his son’s condition.

Dad drove to Dallas to witness Syracuse win the national championship on New Year’s Day 1960. He worked as a ticket-taker at Archbold Stadium then beamed with pride from the bleachers watching his son, JD out of J-D, suit up for the hometown team, living out what he could not: attend school and play a sport rather than work at the plant.

He’d long for the days DaRin rustled through the sports section and pointed at his name on the All-CNY team, back when every writeup didn’t reference the accident and stir up sadness.

“Jim getting hurt just broke his heart,” Janet said, “and he had a hard time dealing with that.”

“It took us a long time to mend our relationship,” DaRin said.

He moved into a downtown apartment to prove he wasn’t going to be a burden the rest of his life.

He returned to Syracuse University. It was a handicap unfriendly campus. Federal laws were still 10 years out.

Admissions pulled out a stopwatch and put him through a test before he could enroll, DaRin recalled: Prove you won’t be late to class.

DaRin ripped his hands to skin wheeling across campus, just to learn he could only take a couple of classes. He couldn’t register for ones that were above the ground level.

He struggled taking notes with bent hands, attached pencils to his fingers to type. The tape player Simmons bought did him no good, DaRin said, when professors wouldn’t allow lectures to be recorded.

Syracuse basketball star Dale Shackleford shoveled out his car in the snow. There were no handicapped parking spots, so he bribed the guard with cigars to let him park up on campus.

He wanted to meet with the Office of Disability Services, on the second floor of Steele Hall.

Call us, they told him.

‘I saw his eyes light up’

He left the university and bought seven acres of land out in Manlius using his court settlement. He built a house on Evergreen Lake to impress a girl, then sat at the dinner table as she dumped him.

He gave up on love and started hanging with old friends at the garage, fixing up his Shelby Cobra and ’67 Mustang GT350. He’d get behind the wheel, hit 120 on the speedometer and feel the wind whipping through an open window, as if he was gliding on that icy pond as a kid.

“Driving is the one thing I do when I’m the same as everybody else,” DaRin said, “and nobody knows I’m disabled.”

DaRin hunted and won archery leagues, then taught the kids in Special Olympics how to trigger a bow with their jaw.

Friends strapped his legs to a snowmobile with a seatbelt, built a back for support and gave him a few words of instruction: Don’t do anything stupid. They toppled him going down the old alpine slide at Song Mountain.

“Hell, I pushed him,” said Jim Jerome, a former teammate. “I take full credit. That was fun. I saw his eyes light up. He was laughing.”

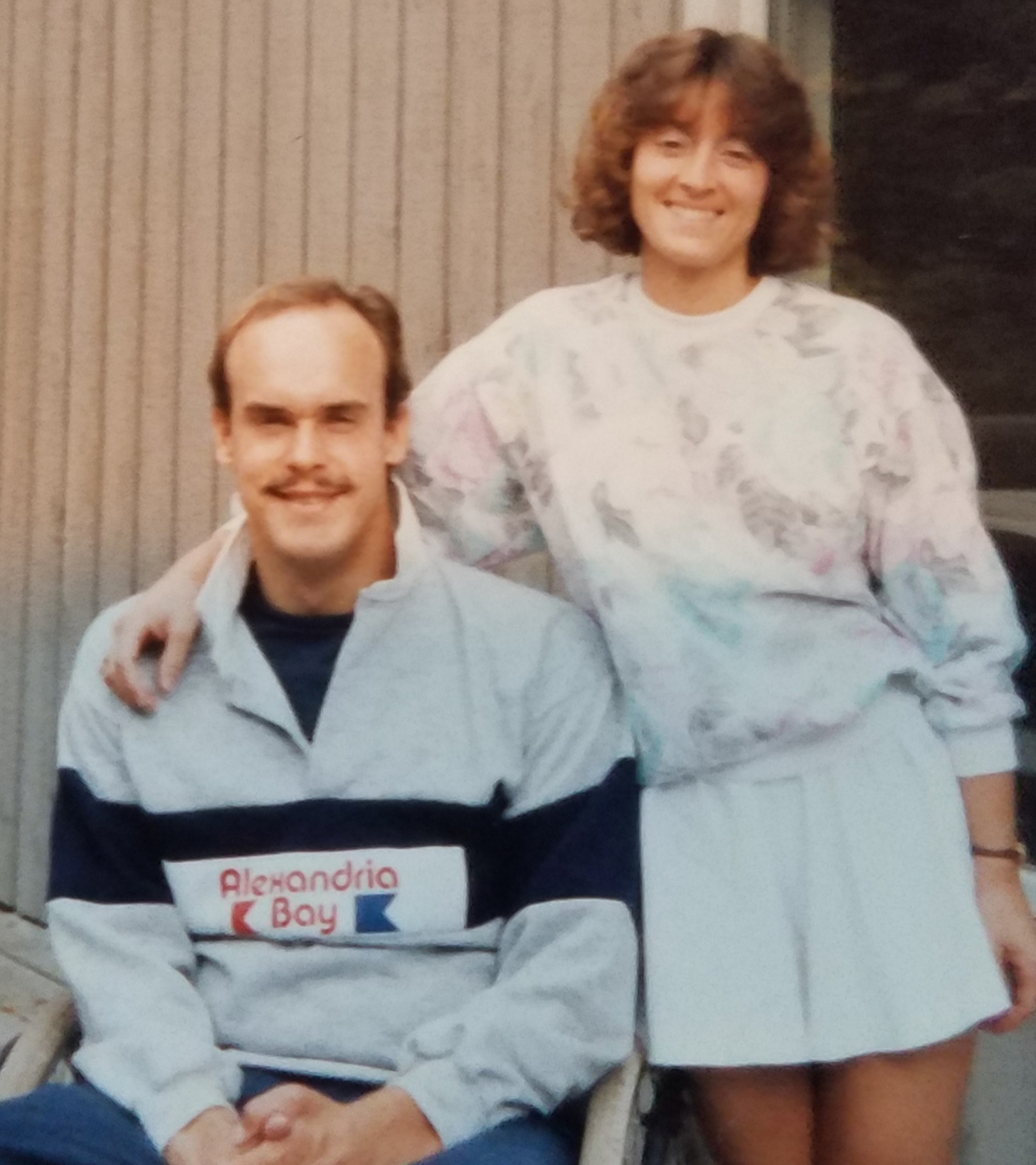

‘He’s my rock’

DaRin became so active, he needed a therapist to stretch out his legs.

When LuAnn King drove 30 minutes out of the way to deliver him coffee and donuts, that’s when his cleaning lady knew.

“James!” she said in her thick Creole voice. “What that girl got to do? Hit you in the head with a brick?”

LuAnn became drawn by his quiet, shy demeanor. She hated men who boasted. He disarmed her with self-deprecating one-liners about his appearance.

They dated for five years to be sure the lifestyle could work. LuAnn fought with the manager at Syracuse Stage to be seated with him in the center aisle, even though they parked the wheelchairs up front. She didn’t blink when the maitre d’ sent out a few guys to carry her date up the steps of a restaurant.

“He’s very good with crisis,” LuAnn said. “I can freak a little more, and he can calm me down. He’s more stable than I am. He’s my rock.”

She wanted kids, and he wasn’t sure he’d be a good father if he couldn’t play catch in the yard.

They attended monthly clinics for couples with difficulties having children, spent nearly six figures trying to start a family. Before the third try — their last — they held hands and prayed: God, if you want this to happen, this is it.

His faith never wavered since the night in the chapel. Too much has happened to him, he said, for the defining moments of his life to be dismissed as coincidence.

His sister married a doctor who sounded the alarm on the severity of his injuries when every minute counted. DaRin wouldn’t have met his wife if he could lay out and stretch his own legs.

“Having faith is not having answers,” DaRin said. “Sometimes you just have to believe and go for it.”

He called his brother with the news: I’m gonna be a father. By the way, they’re twins.

‘He never wished he was living a different life’

Erin and Shannon hung on the back as his wheelchair whooshed down the hallway. They waited until their parents turned away to climb a tree and look high out over the house without fear of falling: We can do this. We’re strong. We’ve got Jim in our bones.

So he can’t hike with his girls. They’ll send him pictures at the summit, then rush home to watch football and eat steak.

People ask: Bet you want to change that day?

Hell no, that day gave me my life.

He has long reconciled the tragedy in taking that summer job, how it wrenched away his physicality and any promise of a pro career yet gave him exactly what he always wanted.

“We don’t care,” Shannon said. “All my friends’ parents got divorced. I have a quadriplegic father, and we’re the closest family I’ve ever seen.”

“What amazes me the most is he could be so bitter, especially because he wasn’t such a normal kid,” Erin said. “He had NFL teams scouting him and looking at him. You could live your life saying, ‘Wow, this is what I could have been. Look at me now.’ That has never happened to him.

“He never wished he was living a different life.”

Another medical scare, and the doctor who saved him

He wasn’t so sure seven years ago, when a septic abscess grew and grew until doctors cut it out, leaving a wound the size of a small melon on his rectum.

DaRin spent the better part of a year recovering from his first major medical scare since the accident, fading away in bed, disconnected from the world.

A wound care center in Syracuse couldn’t close it with infusion therapy. He was incorrectly told he had a bone infection and would die. Father Robert Yeazel rubbed oil on his forehead. The football lettermen sent over the orange blanket they drape over the casket.

When he heard the news, Tom Coughlin, the legendary coach who recruited DaRin to Syracuse, scribbled a note inside the front pages of his book with black ink, the handwriting slanting softly to the right: I know you as one “tough SOB, a competitor and a fighter.”

—

Remember when it is all said and done, how we overcome the obstacles that we face will define us as men!

You have faced adversity in your life with courage and resolve. You are a great example to all! You do not fight alone — remember that!

My best, Tom

—

Given a name for a doctor in Cooperstown, New York, DaRin made a desperate, two-hour drive with his wife and asked for one thing: Give me my life back.

Dr. Thomas Huntsman removed the contaminated tissue, shaved down the bone and grafted healthy tissue using the back of DaRin’s leg. The bone flap procedure is one Huntsman does 100 times a year; DaRin still says the doctor saved his life.

A post-op issue led to a second operation four months later in March 2015. When DaRin woke, he saw Huntsman on his knees with his hands clasped in prayer.

He does that every time, Huntsman told him. He asks the Lord if He’s given him everything he needs to do everything he can for the people he tries to help.

“That touched me,” DaRin said.

“I asked him about what his beliefs are and he said, ‘My belief is the good Lord’s gift to us is life, and our gift back to Him is how we live our lives.’ "

Humanitarian work in pediatric burn centers took Huntsman all over the world. He operated on a boy who got hit by a car begging for food in the street to feed his younger brother. He remembers the smile of a brilliant, outgoing one-eyed girl in the Philippines who finished first in her class.

Huntsman encountered all kinds of pain and horror in his travels, became humbled witnessing such extraordinary examples of human endeavor.

Still, DaRin left an impression.

How was it that this man taught him gratitude? He ponders the question, gazes out his window and sees a clump of dandelions in the middle of his five-acre pasture.

“We all take that for granted,” Huntsman said. “All the beautiful things we drive by and never see. It’s a tiny thing, but when you’re quadriplegic, tiny little things are what your life is made of.

“He can tell you with complete sincerity, at least to me, he’s the luckiest man in life.

“That’s just astounding. I’ve never had anybody with that degree of perspective.”

‘He’s there to support me’

Tom Dane didn’t see a future for himself after the accident six years ago, when the pickup truck he was riding in hit a patch of ice, slid sideways into a pole and flipped several times, ejecting him into the snow and severing his spine from T11 down his lower back to L3.

He spent a month in the hospital, got sent home with oxycodone and self-medicated to combat the anxiety over leaving the house.

Dane needed a flap surgery to treat a deep wound. When he started losing hope, Huntsman gave him DaRin’s number: Try this guy.

DaRin told him about his Mustang and snowmobiles, and soon Dane signed up for wheelchair basketball. DaRin told him about his wife and twin daughters, and soon Dane told him about the girl he dated off and on, who dropped her college studies to be with him while he sat in bed paralyzed.

They celebrated their one-year wedding anniversary last spring with their four dogs. Hopefully, in a few years, kids.

“He’s made the quality of my life better just by knowing he’s out there and he’s there to support me,” Dane said. “Even if we never met in person, I knew if something bad happens to me, where I need something, I know he’d be right there.

“I’m taking in everything. I missed the clouds, the fresh air. Everything is important to me. Waking up and seeing my wife every morning. Waking up and taking my dogs out and having them look forward to seeing me. All my nieces and nephews. I’ve got a lot to look forward to in life, and everything about life right now is beautiful.”

‘Each day is beautiful’

John Lally was a freshman the summer of DaRin’s accident, visited him in the hospital and saw his stretch marks start to scar from the weight loss.

He never forgot it.

Twelve years ago Lally survived an airplane crash in Alaska that, if it had gone a different way, could have left him in DaRin’s position.

“So you sit back and think about the need to be positive and the need to work hard and the need to do the best job you can both on and off the field,” Lally said, “because here’s a guy that would do absolutely anything to have been able to get back on the field and play football that fall.”

He and his wife, Laura, two of the most powerful donors in SU athletics, met with athletic director John Wildhack and an Orange Club staffer to share DaRin’s story and honor him in a way they felt was long overdue.

“We chose to carry Jim’s flag and get him the recognition by the university he deserves,” John Lally said. “He wouldn’t do it on his own. Somebody needed to stand up and tell his story for him.”

They flew the twins in to surprise their dad on Dec. 2, 2018, at the SU football team’s banquet the night it handed out awards and learned it would face West Virginia in a bowl game.

Another secret had been in the works: a new courage award named after DaRin, the keynote speaker.

He turned to Laura before heading to his table: “Why me? Why are so many people here for me? I’m nothing.”

He told his story in painstaking detail, no notes, with a tinge of dry humor: Excuse the scratchy voice, it’s the only one I’ve got.

He thanked his coaches at Jamesville-DeWitt, who told him football mirrors life, with good days and bad ones.

He mentioned the Stryker frame and the metal crown bolted to his head, how the neurosurgeon told his parents he might never leave the hospital.

He described the health scare just a couple years behind him, and the doctor in Cooperstown who gave him what he has always wanted: more time.

He talked about the window in his room, figuring life wasn’t about him, that it was going to go on with or without him, so he might as well join in.

“I will fight through one more time to look out that window to see the sun come up,” DaRin said.

“Because each day is beautiful.”

Each day is a gift.

Don’t waste it.

“It’s courage to go forward after devastation. It’s courage to go forward after tremendous loss,” Laura Lally said. “It’s courage to go forward and do something you’ve never done before. It’s courage to admit that you’re weak or need help. It’s courage that you’re extending your intimate stories to people that may judge you but you may end up inspiring. It’s courage to be vulnerable.”

Laura surveyed the room, certain she saw an offensive lineman at a nearby table wiping his eyes as DaRin finished up and received a standing ovation.

That night in bed, like every night, he flipped to the right to face the sliding glass door. He wants to be sure the first thing his eye catches each morning is the sunrise.

And here, he says, is the honest-to-God-truth of what happens next. He thinks to himself: I got another one. I got another day.

Then he giggles.