Tiny, modular scaffolding can be used to regrow biomaterials to speed repair of injuries and broken limbs.

September 22, 2020

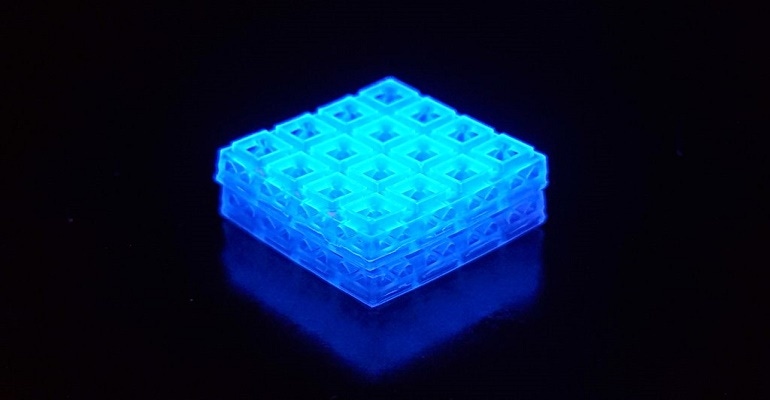

Researchers have used inspiration from a child’s toy to create new 3D printed bricks that could one day be used to heal broken bones, repair human tissue, and even create artificial human organs.

A team at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) designed tiny hollow bricks that can be used to regrow both hard and soft tissue, serving as scaffolding for these new materials and acting as a modular structure that works similarly to Lego blocks, said Luiz Bertassoni, an associate professor in both the OHSU School of Dentistry and the OHSU School of Medicine.

Researchers likened the assemblage of bricks—each of which is 1.5 millimeters cubed, or roughly the size of a small flea—to “microcages,” and said they are aimed chiefly at helping to repair broken bones more efficiently and effectively than current methods.

“Our…scaffolding is easy to use; it can be stacked together like Legos and placed in thousands of different configurations to match the complexity and size of almost any situation,” said Bertassoni, who led the research and worked alongside scientists not only from OHSU but also from the University of Oregon, New York University and Mahidol University in Thailand.

Improved Results

Typically today when someone has a broken bone, orthopedic surgeons implant metal rods or plates to stabilize the bone and then insert bio-compatible scaffolding materials packed with powders or pastes to help foster healing.

In the new method, researchers can fill the hollow blocks of the Lego-like scaffolding with small amounts of gel containing various growth factors that are placed specifically close to locations where they are most needed.

In lab experiments using rats, researchers found that this system created about three times more blood vessel growth near damaged bones than conventional scaffolding material, Bertassoni said.

The two keys to the microcage’s ability to help bones and tissues heal is their proximity to the bones and the biogel that fills each of the hollow blocks of the structures, said Ramesh Subbiah, Ph.D., a postdoctoral scholar in Bertassoni’s OHSU lab.

“The 3D-printed microcage technology improves healing by stimulating the right type of cells to grow in the right place, and at the right time,” he said in a press statement. “Different growth factors can be placed inside each block, enabling us to more precisely and quickly repair tissue.”

Thousands of Options

The microcages can be assembled to fit into almost any space, with more than 29,000 configurations of block segments containing four layers of four-bricks-by-four bricks possible, researchers said. The team published a paper detailing its research in the journal Advanced Materials.

Broken bones aren’t the only type that can benefit from the scaffolding’s healing capabilities, researchers said. They also can be applied to help repair bones that have to be cut out for cancer treatment, spinal-fusion procedures, and also to build up weakened jawbones ahead of a dental implant.

Doctors and scientists also could use the technology to repair soft tissues and even one day use the Lego-like system as the basis to develop organs for transplant surgeries.

Bertassoni and his team plan to continue their research to explore how the microcages perform in repairing more complex bone fractures in lab experiments to continue to improve the technology.

Elizabeth Montalbano is a freelance writer who has written about technology and culture for more than 20 years. She has lived and worked as a professional journalist in Phoenix, San Francisco, and New York City. In her free time, she enjoys surfing, traveling, music, yoga and cooking. She currently resides in a village on the southwest coast of Portugal.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like