Abstract

The emergence of soft machines and electronics creates new opportunities to engineer robotic systems that are mechanically compliant, deformable, and safe for physical interaction with the human body. Progress, however, depends on new classes of soft multifunctional materials that can operate outside of a hard exterior and withstand the same real-world conditions that human skin and other soft biological materials are typically subjected to. As with their natural counterparts, these materials must be capable of self-repair and healing when damaged to maintain the longevity of the host system and prevent sudden or permanent failure. Here, we provide a perspective on current trends and future opportunities in self-healing soft systems that enhance the durability, mechanical robustness, and longevity of soft-matter machines and electronics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Engineering machines and electronics to be smaller, lighter, and less rigid enables them to better integrate into the environment and interact with humans. Such progress has the potential to revolutionize fields such as personal computing and health care by introducing new classes of textiles with digital circuit functionality, epidermal stickers for wireless biomonitoring, and soft robotic systems capable of human motor assistance or therapy. However, removing the hard exterior and making machines and electronics soft and lightweight introduces challenges in design since the materials are required to be simultaneously durable, tough, and load bearing as well as mechanically compliant and deformable. This requirement introduces a potential dilemma in materials engineering that arises from the typical tradeoff between strength and compliance1, which is also common in natural materials and organisms. In nature, organisms address this apparent tradeoff with passive architectures that combine soft and rigid materials with functionally graded interfaces and active mechanisms, such as reversible rigidity tuning and self healing. However, while there has been significant recent attention paid to the rigidity tuning2 and self-healing ability of naturally stiff polymers and composites3, there has been considerably less attention paid to how self-healing materials can also be used to make soft material systems more mechanically robust.

From this perspective, we present an overview of the current progress in self-healing materials that can enable soft-matter machines and electronics to support more extreme mechanical loading without catastrophic failure. This overview includes a working definition of “self-healing” within the context of soft material systems and examples related to structural materials, electronics, and robotic systems, as distinguished in Fig. 1. More broadly, these material architectures fall under an increasingly growing family of soft bioinspired systems for sensing, circuit wiring, and actuation that exhibit many of the same robust mechanical properties as their natural tissue counterparts. These systems are fabricated using a wide variety of materials and manufacturing methods, from deterministically patterned thin-film wavy electronics produced using cleanroom fabrication methods to soft microfluidics and biohybrid systems created using wet-lab soft lithography techniques. As these soft-matter technologies leave the lab and enter real-world environments, they must be further refined or re-engineered so that they can withstand not only stretching, bending, and twisting but also scrapes, cuts, and punctures.

Mechanisms

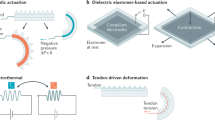

Broadly speaking, self healing can relate to a variety of properties and active responses observed in materials, electronics, and machines (Fig. 2a–c). The underlying mechanisms for self-healing materials and electronics involve the reestablishment of mechanical or electrical contact, which can occur across a range of length scales (Fig. 2d). Molecular mechanisms utilizing dynamic bonds (secondary, covalent, and supramolecular bonds) have been effective in soft materials such as hydrogels, solvent- or moisture-activated systems, and materials above their glass transition temperature4,5,6. When a material is damaged, the molecular networks are severed. Heat or solvents can assist in reforming these networks through molecular rearrangement and can improve molecular mobility to reduce healing time. At the meso- and microscales, self healing is enabled within composite systems through the use of functional particles such as microcapsules filled with liquids, micro/nanodroplets, and solid fillers7,8. When a composite system is damaged, microcapsules release healing agents, microdroplets rupture and coalesce, forming new connections, and solids reestablish contact at time scales dependent on the network mobility. Finally, submillimeter- to centimeter-scale architectures of channels and vascular networks filled with functional fluids can enable self healing9,10,11. Upon damage, these networks reform through rearrangement of material connectivity or can be manually restored to reestablish the preexisting networks. These techniques can be evaluated by a few critical metrics, which include the following: healing efficiency (defined as 100 × [healed strength/original strength]), time to heal, and environmental conditions required for healing.

a–c General schematics of self healing in materials, electronics, and machines. d Self healing can be controlled by mechanisms that occur at various length scales, from molecular interactions (top) and rupture of micro/nanoscale droplets within a composite (middle) to reconfiguration of vascularized networks within soft millifluidic systems (bottom). e For structural self healing, a recovery time of minutes or hours is typically required to restore >80% of material strength. f In comparison, restoration of electrical conductivity can happen at much faster recovery rates—as fast as milliseconds

Examples and applications

Self-healing materials and structures

Creating materials that are strong, soft, deformable, and self healing presents a challenge. One approach has been the use of supramolecular structures with hydrogen bonding. This method has been demonstrated with elastomers that heal under ambient conditions through the rupture and reformation of dynamic hydrogen bonds and coordination complexes4,12,13. Double-network structures with hydrogen bonding can create tough and extensible materials that can heal in the presence of artificial sweat5. Microcapsule approaches have also been demonstrated, in which a PDMS elastomer filled with microcapsules of resin and crosslinker rupture and flow when damaged7. Self-healing PDMS has also been accomplished with a triformylbenzene crosslinker that reacts with polymer chains through reversible imine bonds14. The tradeoff in these approaches is between the time and temperature used for self healing, where lower temperatures require longer times. An approach to overcome this limitation is the use of ultraviolet light to promote local healing6. These examples have all demonstrated the potential to achieve healing efficiencies of ~100%; however, external intervention or extended time scales are still required to achieve self healing (Fig. 2e).

Self-healing electronics

Self-healing electronics exhibit the ability to maintain or recover their high electrical performance and robust mechanical functionality when damaged. Molecular processes have been demonstrated with conductive polymers, such as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS), and semiconducting polymers, where droplets of water or solvent have been shown to restore conductivity to cut films15,16. While these composites have a modulus above the 10 MPa threshold typical for soft materials, effective compliance can be achieved at the system/device level by incorporating the composites as thin films on a soft elastomer substrate. Self healing with soft ionically conductive materials has been demonstrated through reversible ion-dipole interactions of ionic gels17. Reversible ionic interactions also contribute to the self healing of an electrically conductive hydrogel containing polypyrrole and ferric ions18. Composites with rigid fillers or thin-film coatings have been demonstrated with high-aspect-ratio nanoparticles, such as silver nanowires (AgNWs) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs). With AgNW coatings, self healing is accomplished by using a polymer substrate capable of a reversible Diels-Alder (D-A) reaction19. For CNTs, a dynamically crosslinked polymer matrix with low glass transition temperature is postulated to contribute to the reconstruction of the damaged network20. Microdroplets of liquid metal dispersed in soft elastomers have been shown to rupture upon damage to autonomously form new connections with neighboring droplets and reroute electrical signals. As the droplets merge during the damage event, electrical conductivity is continuously maintained, and no external intervention is required8. Channel networks have been demonstrated by incorporating microfluidic channels filled with liquid metal into supramolecular elastomers9. Here, the materials can be cut and pressed back into contact, and mechanical and electrical self healing can be obtained. These examples highlight some of the approaches in restoring electrical functionality when a material has been damaged. Referring to Fig. 2f, this process can happen much more rapidly than the restoration of structural functionality. However, challenges remain in incorporating electrical and mechanical self-healing systems that maintain functionality during damage and heal at rapid time scales.

Self-healing soft robotic systems

Advances in self-healing materials and electronics can enable self-healing robotic systems and actuators. Building on the molecular mechanisms in self-healing materials, thermoreversible Diels-Alder chemistry has been utilized to heal pneumatic actuators21. Self-healing electrical wiring realized using liquid metal microdroplets dispersed in elastomers can drive shape memory alloy (SMA) actuators, where the robot continues to function after sections of the wiring are removed8. Self healing has also been leveraged in dielectric elastomer actuators, where fluidic dielectric layers can self heal after dielectric breakdown. This property allows the actuator to be reused over multiple cycles, in contrast to solid dielectrics, which fail after a single breakdown11. On the millimeter-centimeter scale, soft actuators have been incorporated with tough fabrics to increase tear resistance, while the soft compliance of elastomers allows self healing of small punctures10 and shape recovery after extreme, recoverable deformations22. Self healing in soft robotics is challenging due to the integration of multiple materials and technologies, from elastomeric pneumatic actuators to fluidic sensing electronics and rigid electronic components, which present multiple failure locations. Future opportunities include self healing at diverse material interfaces, monitoring damage in soft systems, and creating robots that can actively repair themselves.

Future directions

While there has been tremendous progress in recent years, there remain exciting opportunities for further advancements in the development of damage-tolerant material systems that support mechanically robust structural, electronic, and robotic functionality. These systems include materials with “embodied intelligence” capable of detecting damage, reporting the event, and healing or adjusting material properties and geometry to mitigate the damage to avoid failure or future damage. Such functionality will require the tunability of the healing response—i.e., controlling variables, such as the repair time, the properties of the resulting repaired system, and how much of the material is healed. Intelligent material response could also be accomplished through system adaptation, where undamaged regions of the material could reconfigure to transfer the mechanical or electrical functionality to unaffected regions. Furthermore, the issues of repeatability (fatigue) and reversibility (recovery) need to be addressed. If damage is sustained in an already damaged or repaired area, how can materials and structures be designed to enhance the strength, toughness, or stiffness of that region over multiple damage cycles? Lastly, actuation and power mechanisms should be considered, where low-voltage electrical operability can provide benefits over thermal, photonic, pneumatic, or hydraulic systems in terms of mass, power consumption, response speed, and programmability of the supporting hardware. Advancements in these areas could provide significant benefits to the robustness and damage tolerance of diverse soft technologies, enabling new generations of human-compatible electronics and robotics for applications ranging from health care and computing to augmented performance and human-machine interfaces.

References

Ashby, M. F. Materials Selection in Mechanical Design 4th edn, (Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2010).

Wang, L. et al. Controllable and reversible tuning of material rigidity for robot applications. Materi. Today 21, 563–576 (2018).

Blaiszik, B. J. et al. Self-healing polymers and composites. Ann. Rev. Mater. Res. 40, 179–211 (2010).

Chen, Y., Kushner, A. M., Williams, G. A. & Guan, Z. Multiphase design of autonomic self-healing thermoplastic elastomers. Nat. Chem. 4, 467–472 (2012).

Kang, J. et al. Tough and water‐insensitive self‐healing elastomer for robust electronic skin. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706846 (2018).

Burnworth, M. et al. Optically healable supramolecular polymers. Nature 472, 334–337 (2011).

Keller, M. W., White, S. R. & Sottos, N. R. A self‐healing poly (dimethyl siloxane) elastomer. Adv. Funct. Mater. 17, 2399–2404 (2007).

Markvicka, E. J., Bartlett, M. D., Huang, X. & Majidi, C. An autonomously electrically self-healing liquid metal–elastomer composite for robust soft-matter robotics and electronics. Nat. Mater. 17, 618–624 (2018).

Palleau, E., Reece, S., Desai, S. C., Smith, M. E. & Dickey, M. D. Self‐healing stretchable wires for reconfigurable circuit wiring and 3D microfluidics. Adv. Mater. 25, 1589–1592 (2013).

Shepherd, R. F., Stokes, A. A., Nunes, R. M. & Whitesides, G. M. Soft machines that are resistant to puncture and that self seal. Adv. Mater. 25, 6709–6713 (2013).

Acome, E. et al. Hydraulically amplified self-healing electrostatic actuators with muscle-like performance. Science 359, 61–65 (2018).

Cordier, P., Tournilhac, F., Soulié-Ziakovic, C. & Leibler, L. Self-healing and thermoreversible rubber from supramolecular assembly. Nature 451, 977 (2008).

Li, C. H. et al. Z. A highly stretchable autonomous self-healing elastomer. Nat. Chem. 8, 618–624 (2016).

Zhang, B. et al. A transparent, highly stretchable, autonomous self‐healing poly (dimethyl siloxane) elastomer. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 38, 1700110 (2017).

Zhang, S. & Cicoira, F. Water-enabled healing of conducting polymer films. Adv. Mater. 29, 1703098 (2017).

Young, Oh J. et al. Intrinsically stretchable and healable semiconducting polymer for organic transistors. Nature 539, 411–415 (2016).

Cao, Y. et al. A transparent, self‐healing, highly stretchable ionic conductor. Adv. Materi. 29, 1605099 (2017).

Darabi, M. A. et al. Skin‐inspired multifunctional autonomic‐intrinsic conductive self‐healing hydrogels with pressure sensitivity, stretchability, and 3D printability. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700533 (2017).

Gong, C. et al. A healable, semitransparent silver nanowire‐polymer composite conductor. Adv. Mater. 25, 4186–4191 (2013).

Son, D. et al. An integrated self-healable electronic skin system fabricated via dynamic reconstruction of a nanostructured conducting network. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 1057–1065 (2018).

Terryn, S., Brancart, J., Lefeber, D., Van Assche, G. & Vanderborght, B. Self-healing soft pneumatic robots. Sci. Robot. 2, eaan4268 (2017).

Martinez, R. V., Glavan, A. C., Keplinger, C., Oyetibo, A. I. & Whitesides, G. M. Soft actuators and robots that are resistant to mechanical damage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 3003–3010 (2014).

Yu, K., Xin, A., Du, H., Li, Y. & Wang, Q. Additive manufacturing of self-healing elastomers. NPG Asia Mater. 11, 7 (2019). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41427-019-0109-y.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartlett, M.D., Dickey, M.D. & Majidi, C. Self-healing materials for soft-matter machines and electronics. NPG Asia Mater 11, 21 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-019-0122-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41427-019-0122-1

This article is cited by

-

A self-healing electrically conductive organogel composite

Nature Electronics (2023)

-

Assisted damage closure and healing in soft robots by shape memory alloy wires

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Progress and Challenges Toward Effective Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells

Nano-Micro Letters (2023)

-

Self-healing liquid metal composite for reconfigurable and recyclable soft electronics

Communications Materials (2021)

-

Homeostasis and soft robotics in the design of feeling machines

Nature Machine Intelligence (2019)