The first wave of the Covid pandemic created the perfect storm for superbugs in the U.S., with cases and deaths from dangerous drug-resistant bacterial and fungal infections spiking in hospitals in 2020, a report published Tuesday finds.

The spike, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report said, wiped out the progress made against the deadly pathogens before the pandemic.

Full coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic

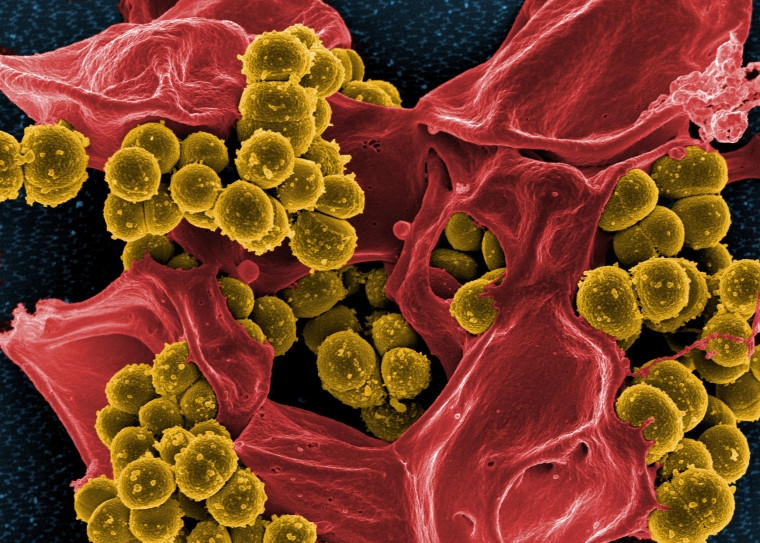

Drug resistance occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites evolve and no longer respond to the treatments that once killed them. The World Health Organization has called drug-resistant pathogens one of the 10 greatest public health threats to humanity.

The CDC monitors 18 drug-resistant bugs in all 50 states and Puerto Rico. The new report, however, included data for only half of the superbugs, because of delays in data collection during the pandemic.

Even that limited data is troubling, experts say.

“The report is concerning on two levels,” said Dr. Arjun Srinivasan, the CDC’s deputy director for program improvement, who worked on the report.

The first is the rise in infections that the agency does have data on. Equally concerning, he said, are the organisms the CDC wasn’t able to collect data on. Those are superbugs that are found more often in the community, rather than in hospital settings.

Superbugs regain ground

The CDC report found that overall, superbug infections and deaths in hospitalized patients increased by 15% from 2019 to 2020, with some worrisome pathogens gaining far more ground.

There was a nearly 80% increase in patients in the hospital who became infected with Acinetobacter, a group of bacteria that can cause blood and urinary tract infections and pneumonia. Infections with another bacteria of concern, P. aeruginosa, which is resistant to multiple drugs, rose by more than 30%. And cases of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales — resistant to the antibiotic carbapenem — increased by 35%.

Experts are particularly worried about a 60% rise in infections with Candida auris, a drug-resistant fungus that health officials around the world have been monitoring since 2009.

C. auris, which “spreads like wildfire,” is particularly good at picking up drug-resistant genes from other pathogens and mutating to resist the few antifungal medications available, said Dr. Luis Ostrosky, the infectious diseases division chief at the McGovern Medical School in Houston.

The fact that different superbugs can pass drug-resistant genes among one another highlights the importance of regaining control over their spread.

“We are not only talking about one single organism pandemic,” said Dr. Cesar Arias, a co-director of the Center for Infectious Diseases Research at the Houston Methodist Research Institute.

Overburdened hospitals

For years, hospitals have honed practices to keep superbugs from spreading among patients.

“We were actually seeing reductions in antimicrobial resistance,” Srinivasan said. “That was something a lot of people said would never happen.”

One way to avoid drug resistance is “antibiotic stewardship,” or reducing the use of antibiotics when they might not be needed. The more often antibiotics are prescribed, the more bacteria have the chance to become resistant to them.

That, in particular, took a hit in the first wave of the pandemic, when doctors didn’t have treatments for Covid. Antibiotics were often the first option given to sick patients, even though they don’t work to treat Covid, which is caused by a virus, the report found.

The strain on hospitals may also have contributed to the spread of such infections, Ostrosky said.

“You have a massive influx of patients who are very much acutely ill, much more than usual for a hospital, and you overwhelm the regular systems. You have to open new units, and you have to staff these units with people who do not usually care for such acutely ill patients,” he said. “Then you have to cover for the possibility of bacterial infections early on.”

Srinivasan made it clear that the report doesn’t reflect a failure of health care workers.

“They did heroic work to take care of patients. What the findings represent is a failure of the system. We have to invest in a better system so that when future pandemics happen, we can not only more effectively combat the pandemic, but the complications we’re seeing, including antimicrobial resistance,” he said.

Ostrosky agreed.

“The Covid pandemic has many more ramifications than we thought other than Covid infection itself,” he said. “I think this really confirms our worst fears.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.