It's easy to be jaded by new battery news. Scientists tinker with chemical formulas, using all manner of exotic materials, only for that research to fade into the dusty annals of academia. But this breakthrough is something different. Scientists with the company Cuberg have crafted a new battery that comes with a way to scale up in the real world.

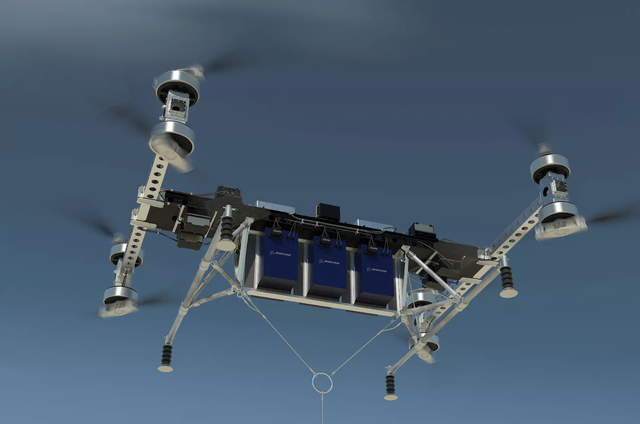

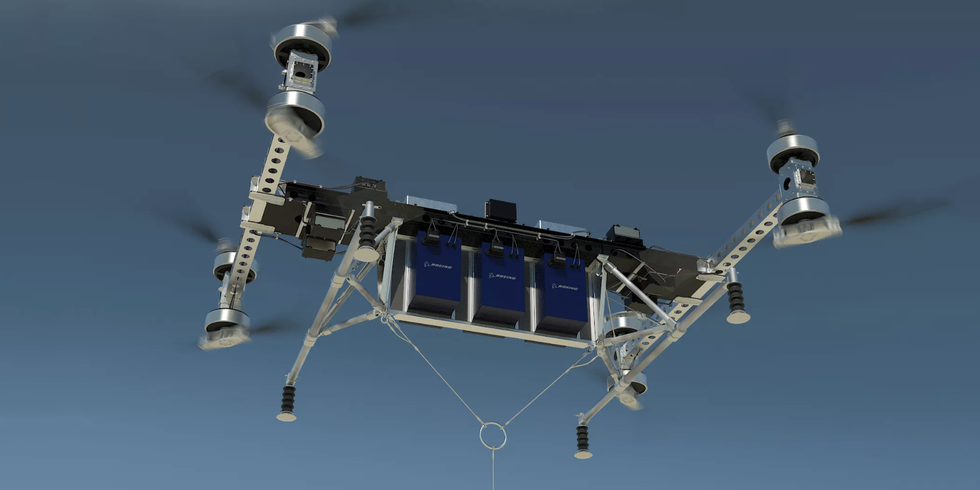

The startup, with backing from Boeing, venture capitalists, and the U.S. Department of Energy, has demonstrated the world's first vertical drone powered by a lithium metal battery (not to be confused with lithium-ion.) The quadcopter flew 70 percent longer than the one powered by a lithium-ion battery.

The key invention is a new, non-flammable electrolyte that erases the safety risks associated with today’s ubiquitous lithium-ion batteries.

“Because it's also chemically very robust and stable, it allows us to use much more energy dense materials inside the battery to cut down a lot of the excess weight in the cell,” says Cuberg CEO Richard Wang. “The material changes from a typical graphite that you find in lithium-ion to a pure lithium metal foil.”

Cuberg sees the ultralight weight batteries as an essential ingredient for cutting-edge aerospace programs, including electric aircraft, flying taxis, and large military cargo drones. “If you look at anything that's flying, lithium-ion batteries are just not good enough,” Wang says. “When you start looking at more ambitious plans, things like Uber Elevate and more futuristic electric planes or hybrid electric passenger airliners, lithium-ion is not going to cut it. It's just too heavy; the performance and economics don't make sense.”

Safety is naturally a critical part of any aircraft, especially one carrying people, so replacing flammable material is obviously desirable. Li-ion batteries are notorious for their combustibility, which happens when overheating causes the flammable electrolyte to vent gasses that react to the cathode, which results in a runaway heating, fire, and explosions.

“The new electrolyte is thermally stable, so even when all the other materials in there are very energy dense and you have overheating, if your electrolyte is stable it greatly mitigates the extent to which this happens,” Wang says. By nipping the thermal runway in the bud, Cuberg says these batteries enjoy great power density and are also safer.

Perhaps the biggest advantage is that the process won’t require big retrofits to bring it to the factory floor, making the tech logistically possible. “People in the battery business say that everything has been done before, in some form or another, typically by some government scientist in a national lab in the sixties,” Wang says. “That's kind of true for our system as well, but historically no one's ever figured out how to use these chemical systems effectively. There's always been challenges of purity, with cost, with basic physical challenges.”

The lithium-ion battery boom has created an entire supply chain that now uses some of the same precursor chemicals used in the Cuberg battery, making it easier to scale production to industrial levels. “When you look at the battery world, there are so many breakthroughs,” Wang says. “But for things to actually can make an impact, you have to go several steps beyond the fundamental materials breakthrough and figure something that works on so many other levels, economically and business wise.”

Cuberg is calling these new batteries a “fundamental leap” in battery technology. If they are right, the flight of the quadcopter could be the trailblazer for an oncoming deluge of unmanned aircraft and passenger aircraft, going places where lithium-ion just doesn’t work.

One logical place to look for this battery to be used is on Boeing’s cargo drone, a 15-foot-wide drone that first flew last year. After that, the sky wouldn’t necessarily be the limit, if the system becomes familiar enough to qualify for use in spacecraft.

But one place you won’t likely see these batteries used is for grid storage, where extending the battery’s cycle life (the time it takes to charge and discharge) is a lot more important than saving weight.

But for those who dream of electrified flying taxis of the future, having a better battery than the Li-Ion is a welcome development.

Joe Pappalardo is a contributing writer at Popular Mechanics and author of the new book, Spaceport Earth: The Reinvention of Spaceflight.