The title track to Guy Clark’s most recent album, My Favorite Picture of You, may be the finest song he’s ever written. This is no small feat. For one thing, there’s his catalog to consider. Guy wrote “L.A. Freeway,” one of American music’s greatest driving songs and the final word for small-town troubadours on the false allure of big cities. His lyrical detail in “Desperados Waiting for a Train” and “Texas, 1947” presents a view of life in postwar West Texas that is as true as Dorothea Lange’s best Dust Bowl portraiture. When he wrote about the one possession of his father’s that he wanted when his dad died in “The Randall Knife,” he made a universal statement about paternal love and respect. Bob Dylan lists Guy among his handful of favorite songwriters, and most of Nashville does too.

And then there’s the equally significant matter of his timing. Those songs were written in the seventies and eighties, when the hard-living coterie of Guy, Townes Van Zandt, and Jerry Jeff Walker was inventing the notion that a Texas singer-songwriter practiced his own distinct form of artistry, creating the niche in which disciples like Lyle Lovett, Steve Earle, and Robert Earl Keen would make their careers. Yet Guy penned “My Favorite Picture of You” a mere three years ago, just after turning 69, an age to which most of his contemporaries had chosen to coast, provided they were still living at all.

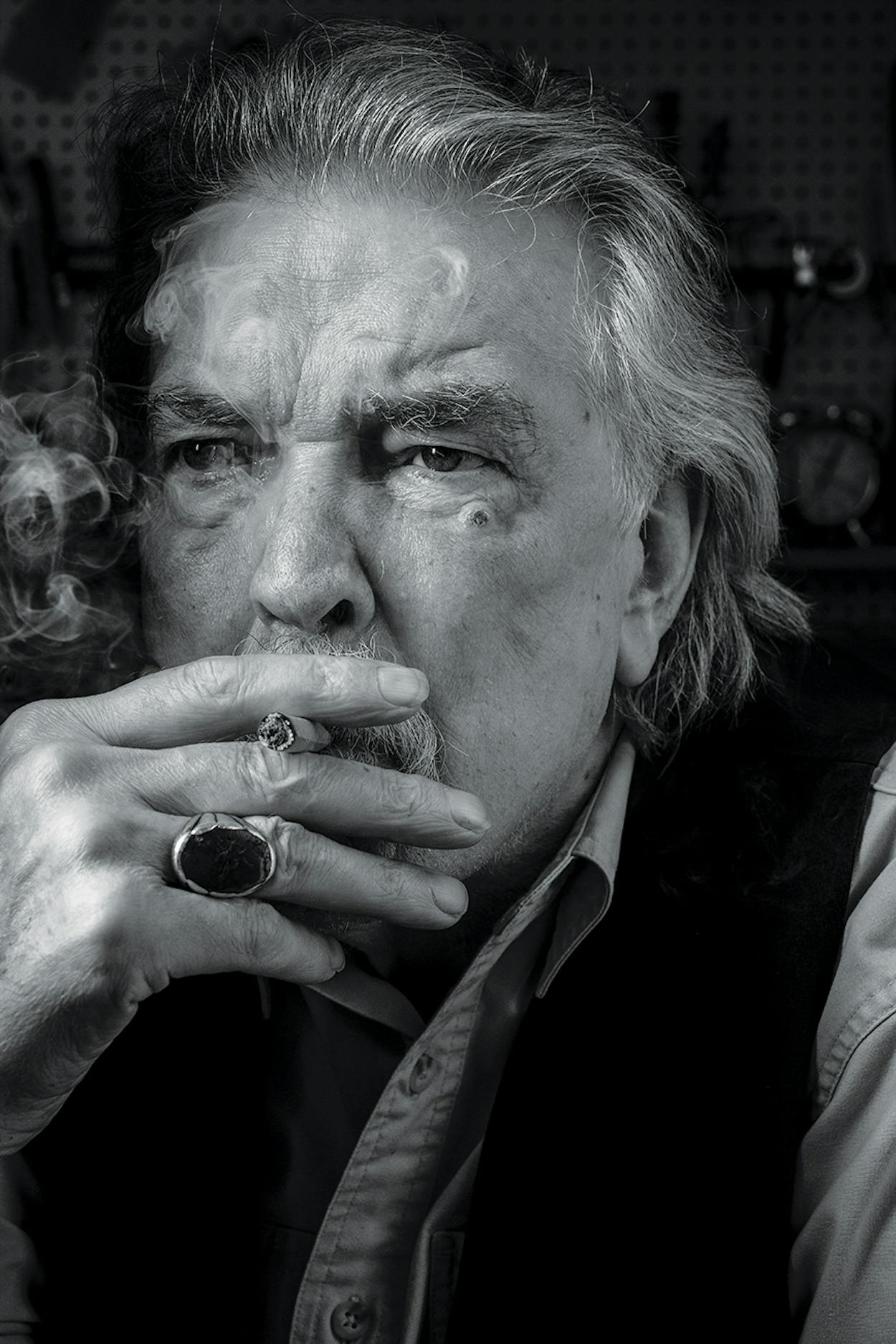

The song originated the way most of them do, with a line. A friend, Gordie Sampson, came to write at Guy’s West Nashville home and brought a hook list with him, a page of potential lines and titles. The two reviewed the list in Guy’s basement workshop, where he splits his time between writing and building guitars, sustaining himself on black coffee, peanut-butter crackers, hand-rolled cigarettes, and an occasional toke of boo. One wall is covered with shelves that hold some 1,500 cassette tapes of demos, live shows, and friends’ albums, and another wall holds luthier tools. The rest of the room is cluttered with the ephemera of his life, some of it stored in little clementine orange crates, the remainder hanging on the walls and scattered on tables. Guy is endlessly loyal, and each item carries a specific sentimental tie. There’s a tight portrait of Van Zandt taken by their friend Jim McGuire. A cane that artist Terry Allen found for him in Santa Fe. Every last piece of a fiddle that Guy smashed on a mantel in a drunken fit forty years ago and still means to repair. And on a stand-up table along the back wall, the actual Randall knife, along with others sent in by fans and a letter of thanks signed by the knife maker himself.

Guy sat across from Sampson at a workbench in the center of the room. A tall man with regal posture, he’s got an angular white mustache and soul patch, wavy gray hair that curls up at his collar, and a woodblock of a forehead that looms over deep-set blue eyes. His general expression is that of someone who’s thinking about something more important than you are. Or at least more interesting.

One line on the list jumped out at him: “my favorite picture of you.” He pointed past Sampson to a thirty-year-old Polaroid of his wife, Susanna, pinned on the wall behind a drill press, a photo taken back when she and Guy were Nashville’s king and queen. In those days the first advice new songwriters heard when they moved to Music City was to find Guy and Susanna. And once young guns like Earle and Rodney Crowell made their way to the nonstop picking party at the Clarks’ kitchen table, their goal quickly became twofold: write a song that Guy dug and find a woman like Susanna. She was gorgeous, with long brown hair and dark bottomless eyes. But her attraction was something more: she was uncompromising, indomitable. A painter and songwriter herself, she insisted budding artists place their craft at the center of their lives, just as she and Guy had. When Guy had started thinking about writing songs as a career in the early seventies, she challenged him to quit his day job at a Houston television station and move to Los Angeles, where they’d live for a year before settling permanently in Nashville. She was smart and cocky but also funny. She started writing songs on a how-hard-could-it-be lark to gig Guy, and then she got cuts. And after Emmylou Harris and Kathy Mattea made the charts with her songs, she liked to tell people, “Guy writes the classics, and I write the hits.”

But the Susanna Clark living upstairs when Sampson came to write scarcely resembled that woman. In the early 2000’s, reeling from the twin defeats of a debilitating back condition and the early death of her and Guy’s best friend, Van Zandt, she’d taken to bed. Though she eventually quit drinking, she upped her intake of pain pills to a point beyond lucidity, seldom leaving the bedroom or changing out of her white cotton nightgown. Then came lung cancer and her refusal to stop smoking. Through much of that time, until his own health turned south, Guy was her sole caregiver. When he went to the basement to work, she’d call on his cellphone and ask him to cook for her or sit and keep her company as she moved in and out of reason. On his walk to the stairs, he’d pass by that Polaroid. It was taken, he told visitors, one afternoon when he and Van Zandt were day-drunk and acting like assholes. She’d had enough and was ready to get as far from the two of them as she could. She stands center frame, arms crossed, glaring at the camera like she might make the photographer’s head combust.

Sampson’s line could only refer to that photo. Guy started into his writing ritual, spreading out sheets of draftsman’s graph paper and grabbing one of the music chart pencils he orders special from California. Methodically, he wrote in all caps, giving each letter its own box on the page.

MY FAVORITE PICTURE OF YOU IS THE ONE WHERE IT HASN’T RAINED YET AS I RECALL THERE CAME A WINTER SQUALL AND WE GOT SOAKIN’ WET A THOUSAND WORDS IN THE BLINK OF AN EYE THE CAMERA LOVES YOU AND SO DO I CLICK“The whole song just kind of poured out,” Guy explained one afternoon a few months ago, sitting in the same workshop, holding the same photo. “I didn’t have to think too much other than to get it all down. Then I went upstairs, sat on the edge of the bed, and played it for her. She said she liked it, I guess. Whenever I wrote about her, she was always . . . I don’t know if ‘touched’ is the right word. She was always flattered. Usually she said, ‘Well, it’s about time.’ ”

That was particularly true in this instance. Susanna’s slide out of life lasted just another year and a half. In June 2012 her heart gave out, and it’s hard now to listen to “My Favorite Picture of You” and not think of it the way Guy describes “The Randall Knife,” as a cathartic piece of writing. Only he wrote “Randall Knife” a couple of weeks after his dad’s death. With Susanna, he tried to say goodbye while she could still hear him.

“I never was much for moaning and crying with this kind of experience,” he said. “This is the only way I know how to deal with it. To get it out.”

In November Guy turned 72, but it must be noted that songwriter years, like dog years, aren’t the same as people years. Nashville writers of Guy’s era lived by a different set of rules than the rest of us. They didn’t punch a time clock. If they went for early-afternoon drinks on a weekday, they weren’t skipping out on work but fishing for lines, scribbling the best bits of conversation on cocktail napkins. When they passed a guitar around after the bars closed, ingesting whatever chemicals would carry them to dawn, they were soliciting reactions to new material, refining new songs. It wasn’t partying, it was writing. But it also wasn’t healthy, and while it may have kept them open to exotic ideas and experiences, it worked hell on their bodies. Those who couldn’t manage their appetites either quit drinking and drugging, like Steve Earle, or died, like the long list running from Hank Williams through Van Zandt. Somehow Guy always maintained just enough control to survive without stopping. And now he’s got a young man’s curious mind atop a body that’s fixing to turn 111.

He musters a rogue’s charm when discussing his physical state. He lost three toes on his left foot in recent years as a result of diabetes. “It began with my big toe,” he says before pausing and gazing off nobly, “or the Great Toe, as some call it.” He’s battled lymphoma to a draw, had both knees replaced, and endured a “Roto-Rooter sinus operation” that effectively killed his sense of smell and an arterial bypass that ended up costing him half a quadriceps. One doc fitted him with a vest defibrillator to manage an irregular heartbeat last July, another soldered closed a hole in his bladder in August, and yet another performed cataract surgery on both his eyes in November. He’s had to cut back on coffee and cigarettes, and he quit drinking altogether when, in his one stroke of good fortune—Guy would dispute the characterization—he lost his taste for liquor following chemotherapy treatments.

But he evinces no regrets, and when he talks about long-ago gigs like the one in Dallas when he and Van Zandt called Ray Wylie Hubbard out of the audience to join them onstage and then snuck out a side door and into a cab while Hubbard was singing—“I don’t remember where we went or what we did; it may have just been to get some cocaine and come back”—you get a sense that every ache, pain, cough, and wheeze has been hard-earned and worth it. “I went to the emergency room with pneumonia a while back and heard the doctor say, ‘Give this man as much morphine as he wants.’ I raised my hand and said, ‘Here! He means me! And I’ve got a hundred dollars in my jeans.’ ”

Those infirmities have conspired to prevent him from performing since the start of last summer. He’s always preferred to play standing up, and with his legs shot, he’s unable to keep his balance. The hope is that with thrice-weekly physical therapy he’ll be booking gigs again this spring. In the meantime, he continues his writing sessions, inviting collaborators to the basement as his doctors’ visits allow. There’s no shortage of songwriters waiting to make that appointment.

Guy occupies a unique place among Nashville writers. His reputation is much like John Prine’s—a songwriter who has maintained a long creative career without an outlandish number of big hits. They both get referred to as songwriter’s songwriters, though as Guy told Garden and Gun last year, “It’s flattering, I guess, but you can’t make a f—ing living being a songwriter’s songwriter.” To be clear, Guy has written two country number ones, and his songs have been charting since the seventies, covered by everyone from Johnny Cash and Bobby Bare to Brad Paisley and Kenny Chesney. But it’s the way Guy has conducted his career, his refusal to write songs to anyone’s taste but his own, that has made him one of the most revered figures in Nashville.

Guy Clark songs are a lot like Guy Clark. Some are dramatic, almost self-consciously so, and others seem to wink at you. They are all intensely personal. “Desperados Waiting for a Train” is about a man he knew, his grandmother’s boyfriend, who took Guy under his wing when he was a boy growing up in Monahans. “New Cut Road” is about a man he wishes he knew, a fiddle-playing great-uncle who stayed in Kentucky when Guy’s other grandmother boarded the family’s covered wagon and headed for Texas. He writes songs about things he values, like loyalty (“Old Friends”), respect (“Stuff That Works”), small gifts that bring great pleasure (“Homegrown Tomatoes”), and trusting your muse (“Boats to Build” and “The Cape”). Running through all of them is Guy’s love of language. “Heartbroke,” which became Guy’s first number one when Ricky Skaggs cut it in 1982, contains more ten-dollar words than the entire country top forty holds at most given moments. The lyrics to “Instant Coffee Blues,” a song about a shortsighted tryst—the couple may have just met or they may be backsliding, but they are clearly not destined for togetherness—read like a Raymond Carver short story.

“What Guy tried to do when he got here,” explains Rodney Crowell, who met Guy shortly thereafter, at the urging of a trapeze artist he encountered while busking in Centennial Park, “was take the values of literature and poetry and put them in song. He didn’t want to just write a hit, he wanted to write something that had real intrinsic value, to wrestle with the human condition and come up with new ways of talking about it that would make people listen.”

Crowell was one of the young writers who started showing up unannounced in the middle of the night at Guy and Susanna’s house. “They’d always make room and pull out guitars,” he says, “and Guy’s first question would be ‘What are you working on?’ Half songs were important. It was like a salon that way. The confidence you’d take playing a half song in that setting would give you the strength to finish it. ‘Till I Gain Control Again’ is one of my songs that that happened with.”

That open-ended encouragement is another reason Guy is so beloved—and referred to frequently as a mentor. “Townes was more of a ‘Go read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee’ kind of mentor,” recalls Earle. “Guy actually showed me how he did things.” Guy also lobbied the publishing company he wrote for, Sunbury Dunbar, to give an untested Earle his first writing deal, in 1975. But Guy doesn’t like to think of that as mentoring. “ ‘Nurturing’ is a better word,” he says. “It’s just trying to make things available to people who deserve a shot.” An even better word might be “advocate,” and not for the advancement of great songwriters so much as great songs. He played an early demo tape of Lyle Lovett’s for everyone he knew in Nashville, helping Lovett secure his first deal. At that point the two had yet to even meet.

His support makes a huge impression. One night in 1997, after one of Jerry Jeff Walker’s annual birthday concerts in Austin, I found my way into an after-hours guitar pull that had broken out in a suite at the Driskill Hotel. Sitting around a large table and surrounded by awestruck fans were Guy, Walker, Hubbard, and Bruce and Charlie Robison, who’d all performed that night, and Monte Warden, who’d tagged along with the Robisons. “Guy asked me to play a song,” remembers Warden. “He told me to play ‘I Take Your Love.’ It had never been a single, never a video, never a nothing, just a buried album cut on a record that sold maybe four copies. And Guy asked for it by title, in that room, in front of those people.” Bruce Robison has a similar recollection. “It was crazy for me just to be there. And Guy asked me to play ‘My Brother and Me’ again [Guy had first heard it onstage earlier that night]. That was the biggest moment of my career up to that point.”

I asked Guy what he remembers of that night. “Oh, they kept asking me to play ‘Randall Knife.’ And I knocked my drink off a balcony down into that absolute chaos on Sixth Street. Luckily it didn’t hit anyone in the head. It would have killed them.”

On a clear Saturday afternoon at the end of August, Guy drove me around Nashville. On the way out of his house I noticed some dozen freshly pressed denim work shirts stacked on an ironing board. They were various colors, all muted, and all the exact same L.L. Bean model. Then I saw Susanna’s painting of the original blue Carhartt version of that shirt. It hangs in Guy’s kitchen now, instantly familiar from the cover of his first album, Old No. 1, released in 1975. That’s been his uniform since at least back then, when newcomers to Nashville who’d never laid eyes on Guy knew they could find him by looking in a handful of bars for the tall pool player with the untucked denim shirt and big turquoise ring on his right hand.

He was wearing that same turquoise ring as he grabbed the steering wheel and pointed us downtown. The first place he showed me was a West End bistro, the Tin Angel. In 1972 it had been Bishop’s Pub, one of the first Nashville clubs to host open mikes. “You could make ten or twenty dollars a night,” said Guy. “When I came here, I had a publishing deal and a draw, something like fifty dollars a week, not enough to live on. Townes and I were still stealing mayonnaise from the mini-mart to survive.” He pointed around the corner. “Susanna and I had an apartment two blocks from here. Every afternoon she and Townes would walk down to Bishop’s and shoot pool.”

Guy and Van Zandt were part of a crop of songwriters who came to Nashville in the wake of Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newbury, and the tumult of the sixties. Their priorities ran more to art for art’s sake, at least compared with the preceding generation, which was typified by people like Harlan Howard, a onetime jingle writer who cranked out an endless stream of radio-ready hits. “Those guys were always at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, which I never went in. Harlan was a sweet man and a good friend, but I just didn’t feel comfortable there. I wasn’t country. I was a folk singer from Texas.”

He’d fallen for poetry as a kid, first in Monahans and then in Rockport, when his family would follow dinner with readings of Robert Frost and Stephen Vincent Benét in the living room. He learned guitar from one of his father’s law partners, then taught himself to fingerpick by studying Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb in the Houston folk scene. That’s where he fell in with Van Zandt and Walker, who encouraged him to move beyond Dylan covers and write his own songs. He got married and had a son, Travis, then divorced and took up with Susanna. After their famously dissatisfying year trying to get Guy’s career off the ground in L.A., they moved to Nashville.

Country music was in a transitional state. Willie Nelson had left town to do his own thing in Austin, and the progressive-country scene he cultivated there had caught Nashville’s attention. The music had a rougher edge than mainstream country, but it was also opening a new market. Nashville wanted some of that audience, and Guy seemed like an artist who could attract it. His music was probably better suited to Austin, where performers made a big to-do of placing art before commerce. But Guy was never one to worry about threats to his artistic integrity. He knew he’d never write a song just to get paid, but he certainly wanted to be paid for what he wrote. “Austin was always a lot more fun than Nashville,” said Guy as he turned onto Music Row, the string of old houses on Sixteenth and Seventeenth avenues that became the center of the country music industry in the late fifties and sixties, when they were converted to recording studios and publishing companies. “But I never much liked doing business from there. Nashville had serious lawyers, not hippie-dippie bullshit. I wanted lawyers who were armed robbers in business deals.”

He stayed in Nashville and recorded for the label Nelson had left, RCA, whose head of country music, Chet Atkins, was an early champion of Guy’s writing. RCA released Old No. 1 and then Texas Cookin’, both of which fared better with reviewers than with radio programmers. But other writers took note, and both albums are now regarded as essentials in the Texas singer-songwriter canon. Then he made three records for Warner Bros., which was attempting to create stars out of hipper artists like Emmylou Harris. But radio didn’t take a shine to the big, busy sound of those albums, and Guy soon gave up all pretense of chasing anything but songcraft. He released his next album, 1988’s Old Friends, on the boutique bluegrass label Sugar Hill. He and an engineer friend tricked out the studio in his publishing company’s basement, where writers would cut demos, so that he’d always have access to a free, first-rate place to record. From then on, he recorded only when he felt ready, typically every three or four years, once he had a batch of ten songs that satisfied his ear. Rather than rely on session players to back him, he brought in other songwriters, like Verlon Thompson and Darrell Scott, who played in service to the songs rather than their own showy licks. His sound took on more space, his lyrics were allowed to breathe.

Many of the records he made in that manner, like 1992’s Boats to Build and 1995’s Dublin Blues, are now indispensable to songwriting fans, and his latest album rates with those. My Favorite Picture of You opens with “Cornmeal Waltz,” a brightly colored snapshot of families spinning in a Hill Country dance hall on a Saturday night. “The High Price of Inspiration” is an acknowledgment—more somber than Guy provides in conversation—of the cost of using drugs to access creativity. When Picture was released, last July, the Los Angeles Times declared it “American songcraft at its finest.” Garden and Gun called it “a bare-bones gem that has the feel of [Johnny] Cash’s much-lauded American series of albums.” It debuted at number 12 on the country album chart, Guy’s highest-ranking studio record since Old No. 1 reached number 41 in 1975.

There was an irony to the timing of the glowing reviews. “I’ve got a hit record, but I’m too f—ed up physically to go out and play behind it,” he said as he slowed to a crawl in front of a two-story red-brick house with a gabled roof and a big sign out front reading “EMI Music Publishing.” This was where Guy had his first office in Nashville. “Back then it was the Combine Music building. Kristofferson wrote here, and Shel Silverstein. Shel also used to come by the house a lot. I think he was after Susanna.

“Having an office was considered a perk. If the publishing company had enough room and you were a big enough writer, you could claim an office. Mine was up there in that little cupola. And around the corner is the little downstairs studio, but it’s about to close. My record is the last one to have been made down there.”

He reached the roundabout at the end of Music Row, then rolled around the forty-foot-tall bronze sculpture of nine dancing figures that was unveiled there in 2003. Musica, as it’s titled, was intended to celebrate the power of song. “This is controversial,” Guy said, nodding at the statue, “because it’s nudes. You can see weenies.”

He snorted half a giggle as he finished the circle and headed toward home. It wasn’t clear whether he was tickled by Nashville’s reaction or by the artist’s failure to anticipate it.

“It’s a fairly interesting city,” he said. “Not my favorite place to be.”

“But you’ve yet to leave,” I said.

“Well, it’s where the f—ing business is. What are you going to do?”

Sometimes when Guy talks about Susanna, he cracks himself up. “She always said she talked Willie into making Stardust. Supposedly she told him, ‘You ought to do a record of old standards,’ and he said okay and asked her to paint the cover. So she got a bunch of books with pictures of stars and came up with that painting. She always said that if you connect the dots, it reads ‘F— Ol’ Waylon.’ ”

At other times he sounds permanently mystified. “She had a guitar but wouldn’t tune it. She painted beautifully, but she’d throw a one-hundred-dollar brush away before she’d clean it. She’d burn eggs in an expensive copper-bottom cooking pan and throw that away. She’d say, ‘This is not about cleaning pots and pans, man. It’s about cooking. It’s not about cleaning brushes, it’s about art.’ That only goes so far.”

And sometimes, in spite of himself, he lets you hear the heartbreak. “I’d been out somewhere and got home around eight o’clock. She was asleep, so I went to sleep. I remember about midnight thinking, ‘Susanna’s awfully quiet.’ I just reached over and touched her, and she was cold. It was too late for CPR or anything like that. Just ‘oops’ . . . and there you go.”

They met in 1969 through Susanna’s sister, Bunny, whom Guy used to call on when he and Van Zandt played Oklahoma City. But shortly after that introduction, Bunny killed herself. “I sat next to Susanna at the funeral, and it just never ended. It was a loss for both of us, and she needed some place to go other than family. I don’t think we were ever apart after that.”

They were also seldom without Van Zandt. When they moved to Nashville, in 1971, he showed up almost immediately and spent the next eight months on their couch. The next year Guy and Susanna took Mickey Newbury’s houseboat down the Cumberland River to get married in Gallatin, and best man Van Zandt rode with them, there and back. When money was tight, the three would go to Music Row parties and load their coat pockets with hors d’oeuvres and whiskey bottles, and when small royalty checks came in, they’d make runs to the liquor store. They fed off one another. Guy and Van Zandt were each other’s most credible supporter and critic. When Susanna wearied of Guy’s occasional dips into sullenness, Van Zandt could always make her laugh. And both Van Zandt and Susanna, who were mercurial, fragile sorts, would come to rely increasingly on the steadiness of Guy.

But some of the original drama always followed Guy and Susanna. Neither stayed faithful when he traveled without her. Guy’s strategy when he came home was to try to make amends. Susanna, who had a hot, jealous streak, would dramatically pack her bags. They addressed each other in song. In “Anyhow I Love You,” Guy wrote, “Just you wait until tomorrow when you wake up with me at your side and find I haven’t lied about nothing.” Susanna, on the other hand, co-wrote “Easy From Now On,” about seeking a one-night lover to “kill the ghost of a no-good man.”

By the late eighties, Susanna had grown tired of all that and, not incidentally, all the cocaine in their lives, and the two separated for nearly four years. “She’d had enough of me and Townes’s bullshit, so she called an attorney and rented an apartment in Franklin [Tennessee].” But they told friends they’d merely switched back to dating, and they never even kind of lost touch. At one point, Susanna wanted to write a song with an old friend who lived in Memphis, and aggravated by how much money Guy and Van Zandt gambled away on the road, she rented a limousine for the two-hundred-mile trip. When she got back, Guy helped her finish the song she’d started, “Shut Up and Talk to Me,” and then turned her trip into a song of his own, “Baby Took a Limo to Memphis.”

“I had to get in the f—ing car and drive out to Franklin almost every day to fix something for her. Finally she realized she couldn’t live by herself. She had to have someone around to take care of her. And I loved her, so it was me.”

That was in 1992, just about the time her back gave out. For the next five years Guy took care of both Susanna and Van Zandt, whose tendency to drink could no longer be euphemized as part of his job. Club owners didn’t want to book him anymore, and most of his gigs were on mini-tours Guy set up for the two of them. Guy would ensure that Van Zandt made it to airports, hotels, and the stage, none of which was easy. Or fun. On New Year’s Day 1997, a week after falling and breaking his hip, Van Zandt had a heart attack and died. And Susanna began her own long, slow descent.

The next fifteen years grew steadily darker. Susanna demanded constant attention, and Guy provided it when he was in town. But he still had to tour to make a living. “He was always on the phone making sure she was taken care of,” remembers Verlon Thompson, who played with Guy through those years. “But nobody really knew any of that, because he’d walk out onstage and sing about the woman whose name was tattooed through his soul.”

On the afternoon after she died, Van Zandt’s son, J.T., called Guy from Austin. For the previous couple of years, Guy had been helping him build a guitar in the basement whenever J.T., a woodworker, could make it to Nashville. Working alone, Guy had finished the guitar and shipped it to J.T., and it had arrived that morning. “He’d given instructions to call as soon as I got it so he could tell me some things I needed to do to preserve it,” says J.T. “So I called, and he said, ‘There’s some slack in the strings.’ I told him I’d heard about Susanna, and he just kept on talking about the slack in the strings.”

Whenever anyone asks Guy about retirement, he jokes that “retired songwriter” is an oxymoron. “Retire from what?” he asks when I bring it up. But he does seem relieved, as harsh as it may sound, to no longer have to look after anyone else. Back when his own ills were starting to make it hard to tend to Susanna, Rodney Crowell and Emmylou Harris used to come lend an occasional hand. “It was heartbreaking to see him go through that with her,” says Crowell. “And it’s sad, but when she passed, I think a little of the light came back on for Guy.”

That light is due in no small part to the person who’s now taking care of him, his girlfriend, Joy Brogdon. “While I was having one of my knee surgeries, my bookkeeper hired Joy to come help. She’d been a nanny and a housekeeper for mostly bluegrass stars. When I came back from the hospital, she was here, and she hardly left. We just hit it off. That may sound strange, but not any stranger than it’s been in the past.”

She’s got a markedly peaceful manner, with long, straight brown hair and soft blue eyes and a singsong voice with which she reminds Guy to take his meds. She makes his peanut-butter crackers in the morning and puts them in baggies to have on hand when he feels his blood sugar running low. She sneaks decaf into his coffee pot and presses him gently to stick to his promised two cigarettes a day. She irons all the work shirts and keeps his calendar. When songwriters and reporters show up, she kicks off her shoes so her footsteps aren’t a bother while Guy works.

“I did everything around the house for forty years,” says Guy. “The wash, the dishes, everything. Now I don’t have to do anything. Joy does it all. It’s a dream come true. Suddenly there’s somebody taking care of my shit, packing my bags, making sure I’ve got strawberries when I want to sit and talk to somebody.”

They like to look out the window and watch birds in the backyard together, mostly cardinals and one pileated woodpecker that’s been working on an elm tree. When another tree had to be cut down last summer, Joy kept the trunk to have a table made. But the sweetest thing she has done for him, at least in the estimation of the friends who know how hard the troubadour grind can be—whether Guy has enjoyed every minute of it or not—is tie a small, red ribbon to the handle of his suitcase. That will make his luggage easier to spot on airport carousels when he gets back out on the road.