Porsche 911: The Rear-Engine Canvas That Spawned a Universe of Custom Sports Cars

The Porsche 911 probably isn’t the first car that comes to mind when you think “custom”—not in a world of rumbling Mustangs, jacked pickups and ground-scraping imports. But in the past half-century, Stuttgart’s backward sports car has become a jumping-off point for personalized performance machines. What’s really remarkable about the world of 911 customs is the sheer breadth of it, the disparate—and downright bizarre—styles branching off in every direction from this one model.

This story originally appeared in Volume 3 of Road & Track.

In every corner of the car community, there’s likely a 911 on hand to represent. Cool, weird, tough, cute, vintage, postmodern, ugly, fast, faster—it doesn’t matter. There is a 911 custom for every purpose, if not exactly for every purse.

Why should this be? Part of the 911’s appeal is its longevity. Porsche has sold more than a million of these weird rear-engine four-seat sports cars over the last 50-plus years. And during all those years, the 911 has been buffeted by the winds of changing fashions, regulation, and technology. The 911’s unique versatility makes it a broad platform for different styles. It’s able to conquer a back road with ease, then commute through traffic in relative comfort the very next minute.

Countless people have become famous, infamous, or at least made their mark with their own expressions of the 911. Alois Ruf, Akira Nakai, Uwe Gemballa, the members of R Gruppe. People who have taken Porsche’s creation and made it their own. Careers made, industries shifted.

And it’s not just outsiders who have created their own takes on the rear-engine legend. The 911 has been the mainstay of the Porsche lineup for most of its existence, and the company itself has also tested the limits of its basic framework by conjuring a wide variety of one-off 911s, from lifted and girded desert racers to show-stand frivolity. And what are Porsche’s 911-based race cars but customs designed around narrow guidelines?

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

You can imagine how difficult it is to choose a shortlist of modified 911s. We make no claim to covering every permutation. But we hope we’ve taken a broad enough view to present the rough boundaries of the known custom 911 universe. No matter where your allegiance in the car world lies, we bet there’s one here that will appeal to you. Or perhaps this will inspire you to create a unique 911 of your own.

—Brian Silvestro

The Obsessive Restomods

Singer-Williams DLS

Singer Vehicle Design is defined by its ongoing quest to create the most beautifully detailed air-cooled 911 restorations in the world. Nothing is forgotten in that mission, the company painstakingly reimagining 964-generation donor cars to become the Platonic ideal of the sporting 911. But the vibe has always been vintage. With its newest project, the Dynamics and Lightweighting Study, or DLS, the company is pursuing a slightly different take on the ultimate 911. And it’s enlisted some heavy engineering talent in the pursuit of weight reduction.

The study itself, at the request of a client with a 1990 964, was a collaboration with Williams Advanced Engineering. It drew on the extensive lightweighting and aerodynamic expertise of the legendary Formula 1 constructor in order to trim every bit of fat possible from the 911. The top-line stuff is obvious: To increase strength and decrease weight, Singer uses magnesium, carbon fiber, titanium, and every other exotic material you can imagine, save for adamantium. That doesn’t just mean lightweight carbon body panels; it also includes a magnesium Hewland six-speed manual transmission.

But when the big weight-saving gains were exhausted, Singer cut a hole sideways through the shifter and installed a carbon-fiber Momo steering wheel with circular cutouts to drop grams without sacrificing integrity. In fact, everywhere you look—from the seats to the hood struts—it appears some maniac hacked into a 911 with a hole punch. The result of all the relentless trimming, drilling, and reimagining is a car with a curb weight of just 2180 pounds, a half-ton lighter than a stock 964 Carrera.

Extensive computational fluid dynamics work informed subtle massaging of the bodywork and underbody. These millimeter adjustments led to better overall aerodynamics, adding downforce without adding much drag. The aero tweaks work in conjunction with special, Singer-specific Michelin Pilot Sport Cup 2s and bespoke EXE-TC manually adjustable suspension components to massively improve cornering performance compared to stock. Featherweight Brembo calipers with carbon composite rotors slow the whole thing down. Supercar braking, suspension, aero and lightweighting tech, in a car that weighs about as much as a first-generation Miata.

With the 247-hp engine from a 964, you’d get modern sports car speed in an unmistakably beautiful retro 911.

But there’s no stock powertrain here. With the help of Williams and the late Porsche powertrain guru Hans Mezger, Singer modified the Porsche flat-six to make 500 air-cooled horses. That puts the DLS’s power-to-weight ratio in Bugatti territory. You’ll have to cut a hypercar-level check to get one, though, as pricing for the DLS upgrades starts at $1.8 million. When you chase the best possible incarnation of the air-cooled 911, every detail is important and nothing is cheap.

—Mack Hogan

Ruf SCR

At what point does a Porsche 911 restomod go so far that it ceases to be a restored Porsche or a modified Porsche or, indeed, a Porsche at all? Wherever that point is, the RUF SCR has blown past it. And what a glorious thing it is. The SCR might look like the best 964-generation 911 ever built, but its body is made of carbon fiber. Its structure and suspension are not Porsche pieces either. The only big chunk of genuine Porsche in this RUF is the 503-hp 4.0-liter flat-six engine, which is basically a version of the Hans Mezger-designed watercooled engine that powered the 997-era GT3. It’s bolted exclusively to a six-speed manual transmission. That powertrain in a car that weighs about 2800 pounds makes the SCR the Porsche purist’s non-Porsche, a digitally remastered Porsche Greatest Hits album. We’ll have ours in Irish Green. At around $800,000, it’s a bargain.

—Daniel Pund

The Fringe

RAUH-Welt BEGRIFF

The Porsche world can be a pretty rigid, insular place. Even 911 customs are often just recreations of past legends. This is part of what makes the creations of Japanese tuner RAUHWelt BEGRIFF so startling. Well, that and the absurdly tall, sometimes three-tier wings and exaggerated over-fenders. Love them or hate them, there is no mistaking an RWB custom 911 for anything else.

Popular with the underground tuner crowd and comically easy to spot, the cartoonish RWB-modified 911s are destined to steal the show wherever they appear. They represent the most ridiculous end of the custom 911 world. They’ve become the default internet-famous Porsches.

RAUH-Welt BEGRIFF, translates to “rough world concept” in German, was born in the Nineties in Japan. It’s the brainchild of master bodywork artist Akira Nakai.

The chain-smoking Nakai has attained quasi-mystic status. Essentially a one-man operation, Nakai hand-cuts each fender and applies his own kits—shipped from Japan—to each car, flying out to wherever his clients are located.

Like the best tuner specials, RWB Porsches take many different forms. Many are built to stun at meets, while others are assembled to carve through canyons. Some even go endurance racing. RAUHWelt BEGRIFF’s 911s are still 911s.

—Brian Silvestro

DP Motorsport DP935

They say if you listen to enough Steely Dan on vinyl, you can actually hear the sound of cocaine. They also say if you spent enough time in Miami dealing with one-off Porsche 911s, you would eventually become a walking brick of the white stuff. The DP Motorsport DP935, with the dramatic, swooping slant of its nose and preposterous speed, is an automotive personification of coke.

Every DP Motorsport 911 began its life as a 930 Turbo. German engineer and DP founder Ekkehard Zimmermann and his crew would dismantle a customer’s car in their garage in Overath, Germany, outside Cologne. Then they brought the beast to life: Each one had a radical slantnose with pop-up headlights, a ducted front apron, a monster spoiler, and flared-out fenders connected by aero-smooth running boards. From the outside, it’s a bizarre car to behold, but the famous DP lollipop warned other aficionados of the menace within.

It was fast in any context, but for a mid-Eighties road car, it was lightning on rails. Zimmermann generally kitted the DP935 with a 3.3-liter engine, capable of doing 0-60 in around 4 seconds. In the late Eighties, our sister publication Car and Driver named the DP 911 one of the five fastest production cars of the decade. Zimmermann founded DP Motorsport in 1973 after producing lightweight fiberglass bodywork for the Kremer Racing Porsche 911 RSR. That 911, with its black-and-orange Samson livery, dominated the European GT Series, a significant humiliation for the Porsche factory team. A couple years later, the Kremer brothers commissioned DP to develop a whole new 911-based chassis for their Le Mans campaign, and over the course of the Seventies would continue to refine the Kremer RSR until it would finally win the 1979 24 Hours of Le Mans. Joining lead driver Klaus Ludwig were Bill and Don Whittington, a couple of life-on-the-edge Americans who would—as close readers of Road & Track know—end up in the pokey after a series of drug smuggling and tax busts in the Eighties.

The Kremer win at Le Mans humiliated the factory Porsche teams and cemented Zimmermann’s legacy. It would also transform DP Motorsport from a somewhat obscure tuner shop to one of the world’s most sought-after builders.

Which brings us to the Eighties, when DP Motorsport started turning out custom 911 road cars for all sorts of shady customers (in addition to some not-so-shady customers like Mario Andretti and Olympic skier Bode Miller). The fun side of the Eighties would be much less fun if not for the slantnose, widebodied Porsches cruising Ocean Drive. The cars sold for well over $100,000 apiece—real money in the Porsche world of 40 years ago.

As for Zimmermann, he turned in his wrenches, retiring in 2020 with a final 930 build that was unveiled at last year’s Essen Motor Show. This one doesn’t have a slantnose.

—Mike Guy

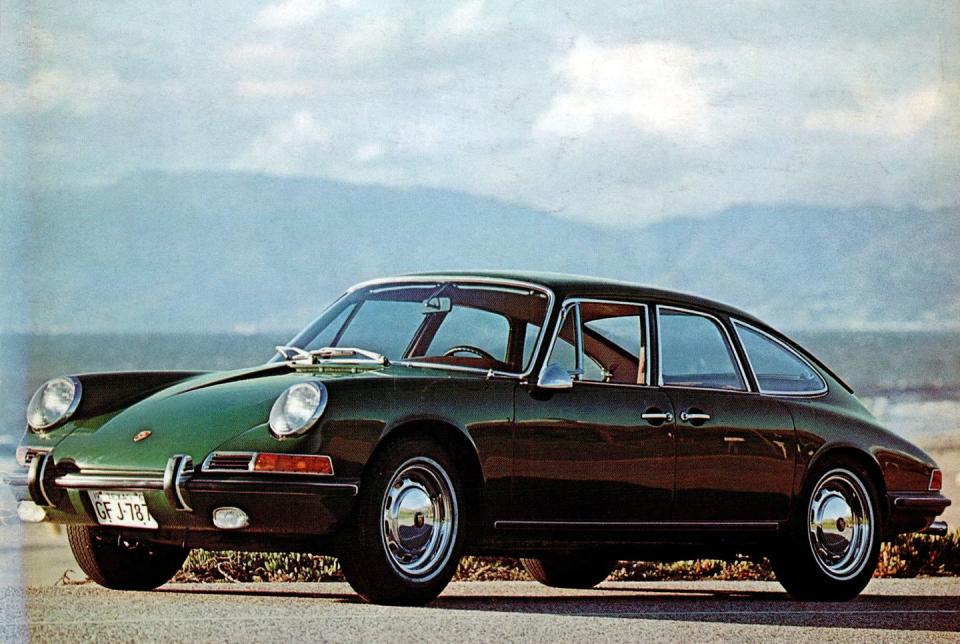

Troutman-Barnes Four-Door 911 S

Long before the Panamera was even a twinkle in Porsche’s eye, William J. Dick Jr. thought a four-door Porsche was a good idea. Such a thing did not exist in 1967, so Dick—a Texas Porsche distributor—commissioned race-car builders Dick Troutman and Tom Barnes to create one. A Christmas gift for his wife, the Troutman-Barnes four-door 911S was first shown on the March 1968 cover of this magazine. Troutman and Barnes cut the donor 911 in half and lengthened the car by 21 inches. The rear doors were factory front doors flipped to opposite sides, and B-pillars and window frames were fabricated from scratch. To turn the 911 into a true luxury sedan, Troutman and Barnes added leather seats, a sunroof, air conditioning, walnut trim, and Porsche’s “Sportomatic” semiautomatic transmission. They ditched the standard Fuchs alloys in favor of wider steel wheels with hubcaps, to cope with the added weight and give a more elegant appearance. We never reported an exact price, but apparently, it was only a little more than a Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow. The Dick car was the only four-door 911 Troutman and Barnes ever built. Porsche only began seriously considering the idea 20 years later with the 989 prototype, which, despite its front-mounted V-8, looked very much like a four-door 911. It never made it to production. We had to wait until 2009 to get a proper Porsche sedan.

—Chris Perkins

The R Gruppe

Rolly Resos's R Gruppe 1966 911

Rolly Resos fell under the spell of the 1967 911 R, the most extreme interpretation of what an early 911 could be. The factory only built 24 of the 210-horse, lightweight model for racing, but it has had an outsized influence on Porsche enthusiasts ever since. It’s been the template for more 911 hot rods than any other single model. Resos found this 1966 911 at European Collectibles in Costa Mesa, California, back in the Nineties, and some interesting parts caught his eye.

“I was looking at it and I noticed the curvature of a factory roll bar,” Resos recalls. “So I walked over and the car had deep six [Fuchs alloys] on it with long studs, early Recaro elephant-foot seats, and I popped the hood and it had a 100-liter fuel tank.” The ’66 was somewhat neglected, but solid and interesting, so Resos bought it. “It was a good car, and I modified it a little bit,” he says. That’s an understatement. Resos installed a fiberglass hood, fenders, and rear decklid, plus louvered plexiglass quarter windows and lightweight taillights, all inspired by the original R—the perfect complement to some choice engine modifications done by a previous owner.

Around the same time he found this car, Resos linked up with fellow R obsessives, Cris Huergas, Ernie Wilberg, and Freeman Thomas (designer of the Audi TT and Volkswagen New Beetle), to form the R Gruppe, a club with the 911 R as its deity and the factory’s Sport Purposes Manual as its holy scripture. Porsche first published the manual in 1968, covering everything a person might want to know about upfitting a 911 for racing. Early 911s were relatively inexpensive when the group started. And, purists be damned, the R Gruppe set about defining its own scruffy, influential aesthetic. The group’s membership is worldwide, but there’s a distinctly California vibe. Resos’s car has that SoCal sprezzatura—carefully considered aesthetics that give off the nonchalant air of a workhorse race car. Resos has worked in the art world his whole life, so this attention to detail is no surprise. He didn’t bother to repaint the fiberglass body panels, giving the ’66 a simple, elegant livery. Resos added decals to complete the look. There’s no such thing as a definitive R Gruppe car, but Resos’s is a great example of a style that’s attracted many imitators. There’s a bit of mystery around this car, too. No one is quite sure who modified it in the first place, though Resos said it lived at Porsche’s Weissach test facility for a few months. And no, you can’t apply to join the R Gruppe. If your 911 is cool, you might get invited to join the strictly limited 300-member club.

—Chris Perkins

The Engine Swap

Lanzante 930 With TAG F1 V-6

During the golden age of turbocharged Formula 1—the Eighties—Porsche was contracted to supply V-6 engines to McLaren under the TAG brand name. To test the motor, Porsche assembled a single 930 with the turbocharged 5-liter V-6 in full F1 spec out back.

The car remained a one-off museum curiosity until 2018, when Lanzante—a U.K. firm best known for converting McLaren F1 GTRs to road-legal spec—announced it would build 11 more, each with an original TAG-branded, race-used F1 engine from 30-plus years ago.

Turns out, McLaren still had nearly a dozen of the engines stashed away and sold them to Lanzante. Each car comes with a plaque detailing race history, drivers, and even finishing positions.

The engines are detuned to 503 hp for streetability, but they still rev to a stratospheric 9000 rpm while pushing 44 psi of boost. The manual transaxle gets custom ratios, allowing for a top speed of 200 mph.

The Lanzante doesn’t look much different from a stock 930 on the outside. In fact, there’s little indication how special this 911 is unless you peer beyond the front bumper, which now houses radiators for the water-cooled V-6. Or you take a close look at the engorged whale tail. But there will be no mistaking its performance, its sound, or its $1.4 million price tag.

—Brian Silvestro

The Legends

1987 RUF CTR "Yellowbird"

There was a time when Porsche leadership lost interest in the 911. By the mid-Seventies, the heads of the company found the froglike sports car outdated. The future was in the front-engine, water-cooled, V-8-powered 928, an on-trend car to rocket Porsche into the gleaming Eighties. Development on the 911 dragged to a halt.

That was an opportunity for Alois Ruf. In 1974, he took over his father’s repair shop in Pfaffenhausen, creating a specialty operation focused on 911s. It became an external engineering department, evolving and refining the model that Porsche had all but abandoned.

When Stuttgart refused to upgrade the 911 Turbo’s ancient four-speed transmission, Ruf made his own five-speed. As Porsche slimmed down the 911 lineup to just the naturally aspirated SC and the Turbo, RUF Automobile GmbH turned them into faster, more powerful machines.

In 1981, newly appointed Porsche CEO Peter Schutz singlehandedly reversed the decision to kill the 911. Five years later, Porsche began building the 959, the most radically advanced 911 variant to date. But Alois had a hell of a head start.

In 1987, Road & Track invited the 959 to its second “World’s Fastest Car” competition. It was a natural fit: a twin-turbo, all-wheel-drive world-beater with height-adjustable suspension and 444 hp. But we also asked Alois Ruf to bring his latest. The car he drove to our shootout at Volkswagen’s Ehra-Lessien test track had been completed just a week before; a fresh set of high-speed tires sat off-gassing in the passenger seats. In the article in the July 1987 issue, we referred to it as “the RUF Twin-Turbo.” The official name is RUF CTR, for Group C turbo RUF. But you know it as the Yellowbird.

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

Next to the technology-packed 959, the Yellowbird seemed rudimentary. It was screwed together so hastily, the radio antenna was taped to the inside of the windshield. But those twin turbos fed RUF’s 3.4-liter engine to the tune of 470 horses, conservatively. Nine cars showed up to our top-speed shootout—including two Ferraris, a Lamborghini, and an AMG Hammer. The RUF trounced them all, blasting to 211 mph with none other than Phil Hill at the wheel. The next fastest car, a Koenig-tuned 911, was 10 mph slower. The Porsche 959 topped out at a mere 198.

The Yellowbird became an instant legend. The top-speed story introduced RUF Automobile to the world. Not long after, Alois set up some cameras and had his pal, Stefan Roser, fling the Yellowbird around the Nürburgring. Titled “Faszination on the Nürburgring,” his oversteering, tire-smoking, edge-of-control lap became the first automotive viral video, passed around on VHS bootlegs and racking up YouTube views to this day.

Just as it’s impossible to imagine Porsche without the 911, it’s hard to envision today’s galaxy of Porsche tuners, hot-rodders, and bastardizers without Alois Ruf. Porsche’s flirtation with a front-engine future inspired him to build the car that launched his legend. In doing so, he blazed the trail for anyone who’s ever looked at a flat-six sports car and thought, “I can make that better.”

—Bob Sorokanich

1974 Porsche 911 IROC

Porsche’s legendarily thick book of options allows buyers an unusual degree of customization—for a cost, of course. If the buyer is Roger Penske and the order is for 15 identically altered cars, well, he can populate an entire race series with some of the most coveted 911-based customs to ever turn a wheel. That’s precisely what Penske did in 1973 when he ordered a batch of 911s in an M&M’s-assortment of colors for the inaugural season of the International Race of Champions, which bridged the late fall and winter months of 1973-74. The cars were the perfect mix of RS and RSR race models, with the upsized 3.0-liter engine of the ’74 Carrera RSR but the more modest fender flares and Fuchs alloys of the 3.0 RS model. They were shipped to America with the familiar ducktail spoilers but were later fitted with the whale tails that would arrive for ’74 and come to define 911 style in the Seventies and Eighties. How would one make such cars even more appealing? Allow only the world’s 12 best drivers to race them in front of television cameras. It’s no wonder road-going IROC tributes are still a hot commodity.

—Daniel Pund

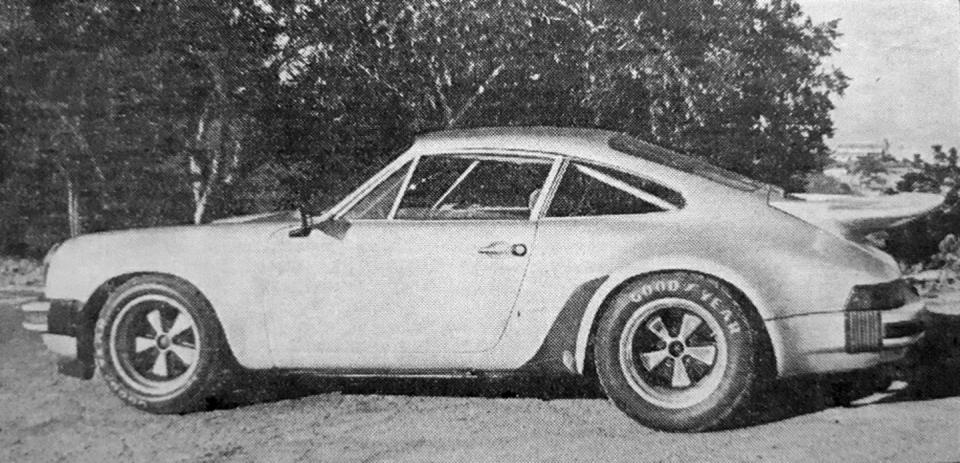

Chris Banning's Mulholland "RSR"

From about 1960 to roughly 1983, a 1.8-mile stretch of Mulholland Drive between Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley was Southern California’s center of speed. On that undulating stretch of pavement, Porsches, Corvettes, Datsuns, Mini Coopers, Mustangs, and Camaros met to chase one another for late-night glory. This is the greatest glory hog of them all: Chris Banning’s 1973 Porsche 911 “RSR” with a 3-inch chopped top. It never lost on Mulholland.

“It’s a bunch of Porsche components,” Banning explains. “Three feet of the front and 3 feet of the back are from a 1975 Porsche. The floorpan, roof and dash assembly come from a 1972. The front bulkhead is from a 1967. Arnie Verbiesen had been racing it in SCCA A-Sedan, but when he laid back the windshield they booted him out of the class. I bought it as a shell for $1300.”

Seam-welded and reinforced with an aluminum roll cage, Banning built the 2260- pound mutant with a stiff structure and compliant suspension to handle the divots and tight turns on Mulholland. The engine, assembled by the long-gone Bozzani Porsche dealership, started as a 911 S 2.4 with 2.8-liter barrels and pistons, RSR cams, ported heads, and mechanical fuel injection for instant acceleration. “It feels like 300 horsepower to me,” says Banning. “It’s beaten 930s.”

Banning’s 911 survives—on Fuchs wheels from one of the original IROC Porsches and Goodyear Blue Streak racing tires—in the garage at his house just off Mulholland Drive. Right now, the car is in pieces. He swears it will roar again.

—John Pearly Huffman

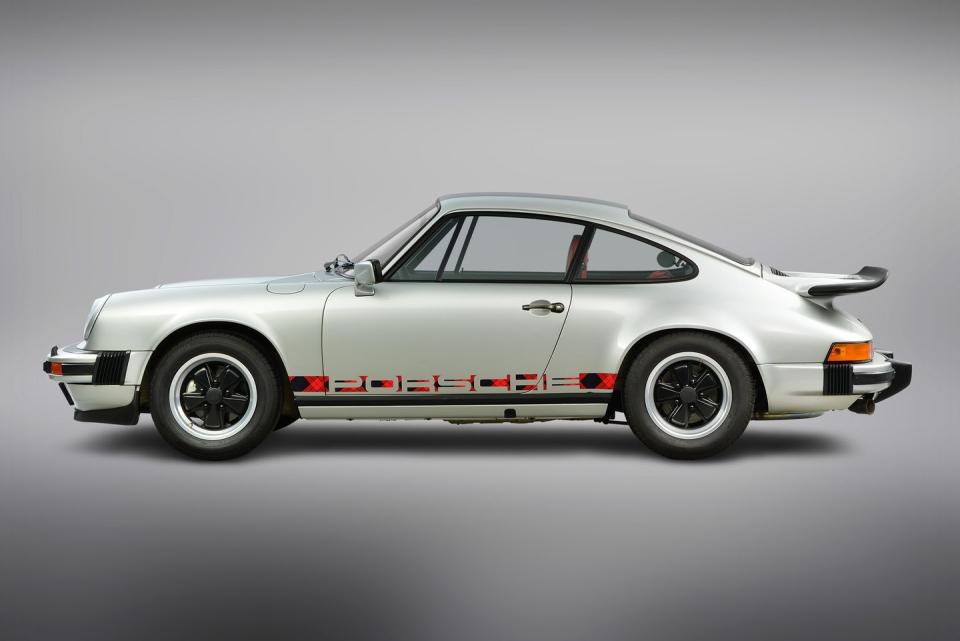

Luise Piëch's 911 Turbo

The best factory-custom Porsches went to the very well connected. Louise Piëch, daughter of founder Ferdinand Porsche and mother of eventual VW Group CEO Ferdinand Piëch, enjoyed a number of custom 911s, including the very first 911 Turbo, a gift for her 70th birthday in 1974. Her car was subtle, eschewing the wide bodywork that distinguished the Turbo along with any Turbo badging. If you didn’t know, you’d assume this was just another Carrera. Piëch seems to have preferred fabric upholstery, and her Turbo is trimmed with a lovely red-and-blue tartan on the seats and door cards that’s echoed in the “Porsche” door decals. She also requested a windshield with no tint. Apparently, she liked to drive to the Alps and paint landscapes from inside the car, and didn’t want tinted glass to color her view.

—Chris Perkins

1967 911 R

The hot-rod 911 story starts here, in 1967, with a clenched fist of noise and fiberglass called the 911 R. According to Porsche lore, race chief Rico Steinemann and his colleague Dieter Spoerry were eying the winter months between race seasons, musing over empty pint glasses, as you do, when the topic of breaking endurance records came up.

Months later, at Italy’s Monza circuit, Steinemann’s team set out to cover 20,000 kilometers at pace to snatch a glut of average-speed records back from Toyota. Porsche brought in its swoopy, mid-engined 906 for the job. But Monza’s brutal, high-banked curves made mincemeat of the 906; the Porsche prototype’s delicate frame and spindly struts were walloped by the circuit’s moonscape asphalt.

Steinemann phoned for backup. Two 911 Rs were dispatched overnight from Germany: one car to rewrite the record books, another as organ donor. The Rs were flyweight 911s built the year before, motivated by a 210- horse, 2.0-liter flat-six borrowed from the 906 itself. Extensive use of fiberglass allowed for an 1800-pound curb weight, making the R the lightest production 911 to ever leave the factory. The door handles were even made from epoxy plastic. They might have been only grams lighter than their steel counterparts, but Porsche was making a point: No detail is too small in the pursuit of glory.

Swiss ace Jo Siffert (and his mustache) led a group of drivers on the record push. They wrestled the 911 R against driving rain, the brutal track, and red-eyed fatigue, but the Porsche and its pilots held firm. Four days later, the 911 R had covered 20,000 km at an average speed of 130 mph.

While just 24 examples of the R were ever built, that blast through the Italian rain set the blueprint for every Porsche hot rod that came after. A modded 911 should be lighter, louder, stronger, and meaner than the rest.

—Kyle Kinard

The Dirty

1978 SC Safari/1984 Rally Dakar

Porsche has long been a glutton for punishment. It has publicly pushed its cars to the limits at the world’s most difficult and grueling events: the 24 Hours of Le Mans, Carrera Panamericana, Targa Florio, and Rallye Monte Carlo.

The Safari Rally and the Paris-Dakar Rally are something else entirely, though. The Safari ran for 3000 miles through the inhospitable terrain of East Africa. And the Paris-Dakar was a three-week-long epic that saw hundreds of competitors in cars, SUVs, trucks, and on motorcycles crossing continents in a true test of durability, speed, and endurance.

For the 1978 running of the Safari Rally, Porsche prepared two Martini-sponsored 911 SC 3.0s by raising the ride height, fitting underbody protection, and mounting a row of Cibié lights behind a tubular brush guard. A submerged rock damaged one of the Porches while it was leading the race, and the team finished a respectable second and fourth place.

Six years later, Porsche would present another ground-breaking dirt racer at the 1984 Paris-Dakar race. What appeared to be a jacked-up 911 was actually a heavily modified car, built specifically for the event, called the 953. It had a manually controlled four-wheel-drive system and upgraded suspension, yet weight savings from a stripped interior kept it below 2700 pounds. And it put out 225 hp from its 3.2-liter flat-six.

It dominated, taking first place overall. It also started a trend. The 953 was the first sports car to win Paris-Dakar, and other manufacturers started entering modified sports cars soon after. Even Porsche saw more opportunity, replacing the 953 in 1985 with the ultra-advanced 959.

For a car that only raced once, the 953 had an outsized impact on the 911. Many of the parts developed for the 953 were further refined for the 959. It was a Carrera 4 years before Porsche ever considered adding an all-wheel-drive model to the 911 lineup. And it made people want to take the 911 off road.

Every modified 911 with rally lights, knobby tires, and off-roading pretensions can trace its roots to the SC Safari and the 953. Like sports-car racer Leh Keen’s side hustle, the Keen Project. While Keen doesn’t add all-wheel drive to older 911s, he creates cars that are as happy off-road as on. They revive some of the most unusual, and dirtiest, custom 911s. As an added benefit, they also turn speed bumps into opportunities to get a little air on a daily basis.

—Travis Okulski

SIGN UP FOR THE TRACK CLUB BY R&T FOR MORE EXCLUSIVE STORIES

You Might Also Like