Fiona hasn’t had a good night’s sleep in 22 years.

It started when her parents got divorced. She was six, and the anxiety of watching their marriage fall apart manifested itself in long, sleepless nights.

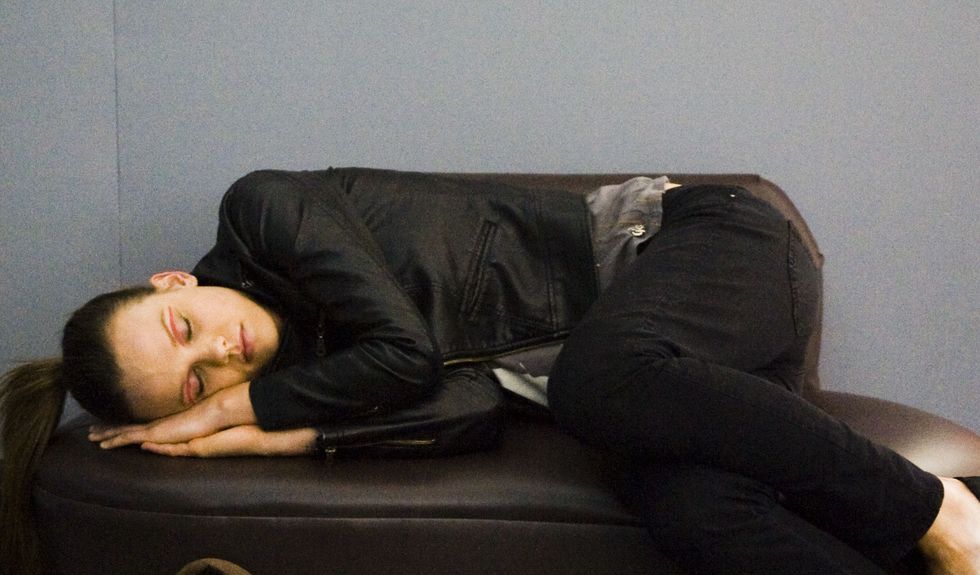

By her teens, it could be hours– three, four, sometimes more – before she fell asleep, and when she did finally drop off, it was in valueless half-hour stints through what was left of the night. She thought it would stop as she approached her twenties. It never did. ‘The worst part was finally getting into a deep sleep, only to have the alarm ring minutes later,’ she says.

For anyone who hasn’t experienced insomnia, it’s near-impossible to imagine the frustration and pain of not being able to get a good night’s sleep.

Our Sleep Hygiene Obsession

Once upon a time, we thought throwing whale music, scientifically proportioned pillows and hypnotising aids at the problem would help. It didn’t. As a culture, few of us have understood the true value of deep sleep.

For decades we fetishised those power figures – such as Margaret Thatcher, Steve Jobs and Marissa Mayer– who claimed to need only four hours’ shut-eye a night. Not anymore. Sleep is now one of the most studied health conditions in the medical world (in 2017 the Nobel Prize in Physiology Medicine went to three scientists who figured out the gene responsible for regulating our circadian rhythms), with disrupted sleep now thought to be connected to everything from obesity to cancer.

The exact figures on insomnia are hard to pinpoint, bearing in mind that so many cases go unreported or undiagnosed (such is the lack of importance we have traditionally given to it). But the estimation is that around 30–50% of the UK population will experience its symptoms at some point in their lives.

Over the past 10 years, the number of prescriptions written for melatonin (the sleep-regulating hormone) has increased tenfold, and sales of over-the-counter sleep aids are rising exponentially. ‘We spent the 1980s and1990s learning how to move and the 2000s learning about superfood and diet,’ says Dr Guy Meadows, co-founder and clinical director at The Sleep School in London, who cites the three pillars of health as movement, nutrition and sleep. ‘It’s only natural that once we have a grip on the first two, we [can now] focus on the third: sleep.’

But Are We Getting More Sleep?

Ironically, our new-found interest in sleep hygiene does not equate to us getting more of it. According to research, over the past five decades our average weekday sleep duration has decreased by 90 minutes, down from eight-and-a-half hours to under seven, with 31% of us getting fewer than six hours of good quality sleep per night.

There are a number of factors contributing to this – the most obvious being longer working hours necessitated by the rise of a ‘never off’ tech culture, the fallout from a global recession and the glamorisation of Silicon Valley’s high-achieving micro-sleepers, such as Twitter’s Jack Dorsey and Apple’s Tim Cook (nicknamed the ‘Sleepless Elite’ by The Wall Street Journal).

But the main insomnia-enhancing culprit appears to be circadian disruption. Your circadian rhythm – a 24-hour internal clock that runs in the background of your brain – is primarily regulated by light, with photoreceptors in the eye responding to changes in light and dark, connecting directly with the part of your brain that regulates your internal body clock.

With the majority of us endlessly surrounded by artificial light, including the blue light emitted by our devices, our circadian rhythms are shot. One study found that reading an e-book, four hours before bed for five nights in a row, delayed melatonin release by more than an hour and a half, shifting the circadian rhythm to an entirely foreign time zone. So if you scroll through Instagram every evening, you’re likely pushing your body clock back to somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean.

The Sleep App Cult

Acutely aware of the issue, over a quarter of UK adults say that improving their sleep is their ‘biggest health ambition’ but most are at a loss for how do to it.* This is where the world of sleep aids (consumer sleep technologies or CSTs) comes in.

In 2009, one of the very first mass sleep aids hit the market. The Sleep Cycle app, created by a Swedish developer, purports to be able to track when someone is in REM (deep sleep). Since then, the market has exploded. Phone apps have had the most success and, like Sleep Cycle, most work by utilising your phone’s accelerometer(the technology that knows when it’s being moved) and microphone to detect your movements, which, depending on their strength and frequency, might indicate how deep your sleep is. The idea is that you can use this data to your advantage, such as knowing the optimum time to set your alarm and how track your improvements.

Over 20 years after her first bout of insomnia, Fiona, now 28, turned to a sleep app. ‘I thought monitoring my sleep would make me feel more settled,’ she admits. ‘And that if it was good quality or I reached certain achievements, such as the length or quality of sleep on the app, it would relieve some of the anxiety.’ In fact, it did the opposite: ‘I found myself number crunching every morning. It became an unhealthy obsession. If I didn’t hit targets – enough sleep or deep sleep – I’d convince myself I wouldn’t function as well that day.’

This fed her neurosis, increasing her anxiety about sleep and further exacerbating the initial problem. And so by collecting data to fight the disorder that had plagued her entire adult life, Fiona had unwittingly landed herself with another sleep-affected disorder: orthosomnia.

What is Orthosomnia?

Coined by a team of sleep experts in a 2017 paper,** ‘orthosomnia’ is the fixation on having a perfect night’s slumber, which has been aggravated in recent years by the use of apps.

The team saw orthosomnia – which translates as ‘correct sleep’ – occurring more and more in their clinics, and flagged this via the widely picked up medical paper. ‘We saw individuals with mostly normal sleep who became obsessive about tracking their data,’ says Kelly Baron, one of the paper’s authors and director of the Behavioural Sleep Programme at the University ofUtah. ‘But the more you try to control your sleep, the worse it gets.’

The issue is not the technology (radio waves or even blue light) but the psychological cycle these apps can trigger. Users are so obsessed by data that they’re stressing themselves out of sleep. Due to the correlation between a quest for perfection and health, it’s comparable to orthorexia, where obsessive levels of healthy eating lead to psychological weight loss issues (which is why Dr Baron and her peers named the condition ‘orthosomnia’).

Think about it: giving someone the means of tracking their sleep is not unlike giving someone who is obsessed with their weight a pair of scales: an instrument that will hone in on their failures and flaws in their quest for perfection. ‘Becoming obsessive about your sleep hygiene (the habits and practices conducive to sleeping well) is the problem,’ says Dr Meadows. ‘It’s actually about doing less.’

As our fixation with perfecting slumber grows, the sleep aid market, although still relatively new in the health world when compared with diet and exercise, is estimated to be worth £64 billion by 2020. That could buy you the world’s most expensive bed – a £5 million hand-carved, 24-karat gold number that, if you wish, which can be accessorised with diamond buttons – 10,000 times over.

But it’s not just the amount of wealth there is to be made from sleep apps – thanks to download charges and monthly fees – that has developers salivating. It’s the potential for the amount of data capture about you and your lifestyle that they’re really excited about.

‘For the manufacturers, sleep trackers are providing them with a huge amount of data.’says neuroscientist and neuropsychologist Professor Gaby Badre. ‘At best this would be exploited to improve the CST.’

But at worst? With data now the most valuable commodity in the world,** the information sapped from your trackers (age, weight, height, location, vocation, lifestyle, diet) could also be worth a pretty penny to third-party companies who are longing to get their hands on these sorts of personal details. Even if they’re not passing it on (always check the terms of service), hackers could be poised to hijack it, as they have done before with exercise app Fitbit.

Data theft aside, the main issue with these apps is that, well, they’re not actually doing their job. Most in-phone apps don’t have a way of truly identifying your level of sleep.

‘The gold standard method of measuring is to attach electrodes to someone’s head to measure the brain’s electrical activity to identify what’s happening. Beta waves indicate light sleep; delta waves are a sign of deep, rapid eye movement (or REM) sleep,’says Dr Meadows. ‘If you’re relying on an app that is just measuring movements, it’s purely making assumptions based on movement alone.’ That can create, as Meadows puts it, an ‘endless game of tug and war’ of you trying to beat numbers that are likely redundant. If you do have insomnia, the way to face it is by dealing with the cause of it, rather than trying to cheat it with aids.

The truth is, true insomniacs need to find the root of the cause through a sleep doctor or psychiatrist. This might lead to cognitive behavioural therapy, focusing on coping mechanisms and changing the course of thinking. But for those just wanting to improve their current sleep patterns, ‘mind-body therapies’ such as meditation and yoga have been found as the most scientifically approved ways to help with sleep.

Ditching The Apps For Better Sleep Hygiene

As for Fiona, ditching the apps led to immediate improvement in her anxiety and obsession with sleep. No more monitoring, no more number crunching, no more being told by her phone that she was failing. Insomnia still occasionally sneaks in uninvited but, more often than not, she relishes nights full of what she feels is deep, blissful sleep. And she hasn’t got an app to tell her otherwise.

*Aviva, October 2O16. **Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, February2O17. ***The Economist, May 2O17. Photography: Andi Elloway/thelicensingproject.com, Donna Trope/Trunk Archive.