The Life and Times of Frank Zappa

A Bill & Ted star unearths the holy grail of Mothers of Invention lore, albeit in miniature, in a new, most excellent documentary.

During the time Frank Zappa was fighting prostate cancer, to which he succumbed in 1993 at age 52, an old friend and fellow lifelong FZ obsessive generously invited me to accompany him to a couple of the “margarita Fridays” Frank’s staff had initiated as a therapeutic break from the composer’s otherwise strictly workaholic ways.

We’d drive to the Zappa family’s home in the Hollywood Hills and chat in the kitchen with his wife Gail before proceeding downstairs to Frank’s studio and workspace, a.k.a. the Utility Muffin Research Kitchen. Though obviously weakened by his illness, Frank couldn’t have been more gracious and loquacious. He was a consummate host.

During one memorable evening, while eating Beef Stroganoff, he riffed sardonically about whatever atrocities were flickering on CNN. Afterward, he played his Synclavier magnum opus N-lite for us over a spectacular six-channel stereo system as we listened in awe to the densely maximal sound of a lifetime’s worth of music distilled into 18 cosmic minutes (or at least that’s how I heard it). And after a few hours, as we started saying our goodbyes, he insisted we hang out with him even longer simply because, “I am an entertainer, and it is my job to entertain you!”

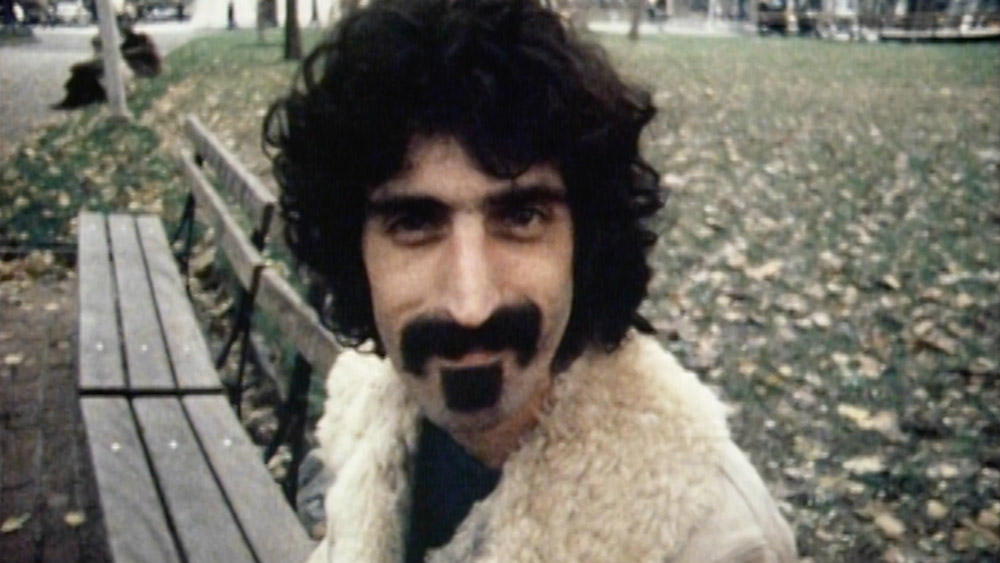

Not only was Frank approximately twice as cool in person as I could ever have imagined (having checked my journalistic detachment at the door), he was both fully present and unexpectedly human. A scruffy beard had replaced his by then trademarked mustache and soul patch. At this point in his life, he was more serious composer than satirical rocker, more deeply informed political commentator than Sheik Yerbouti or The Man From Utopia. And that Frank Zappa, I’m happy to report, is the Zappa I recognized in ZAPPA, a revealing new documentary by director Alex Winter.

A Hollywood actor best known for his starring role in the three Bill & Ted movies alongside Keanu Reeves, Winter made a midcareer pivot to documentarian a decade ago. Prior to spinning the correct spells and earning Gail’s trust in 2015—and thus receiving “the keys to the castle,” as son Ahmet Zappa puts it during our three-way Zoom conversation—Winter wrote and directed films such as Downloaded (which focuses on the impact of internet file sharing) and Deep Web (which explores bitcoin, Silk Road and the dark nets).

ZAPPA, however, “had more emotion, drama and challenges to an order of magnitude beyond almost anything else I’ve worked on, and I’ve been in this business since I was nine years old,” Winter says. “I told Gail, straight up, that I was not a Zappa maniac. I didn’t talk to her about the time signatures in ‘Inca Roads;’ I talked to her about his relationship with Václav Havel, his sexual politics and his art. And we talked about how he made films and revolutionized aspects of the musical recording process.”

And what did Gail want from the world’s first authorized documentary about her husband? According to Ahmet: “The most important thing for my mother was, ‘How do you convey what it’s like to be a composer?’”

***

“Most of this material has never been seen,” reads an early title card in ZAPPA. It suggests that the film’s real star may actually be the Vault, where Frank kept, well, everything.

“My first holy-fuck moment,” Winter says with a laugh, “was when they opened its door. Those gummy YouTube videos do not do that thing justice.” Having visited the Vault, I can attest to the floor-to-ceiling, row-after-row abundance of master (and minor) tapes, housed alongside a treasure-trove of visual ephemera. It was all stored in a massive climate-controlled subterranean facility excavated out of the Zappa family’s front yard (real estate now owned by Lady Gaga). “Frank’s life was down there,” Winter says.

To even begin the film, that life had to be preserved. Winter and the Zappa Family Trust launched an elaborate yearlong Kickstarter campaign that raised more than $1.1 million to rescue a vast amount of endangered media. Most of that money was spent on “predigitizing” the material. “That’s saving it so you can digitize it,” Winter explains. And at the end of the two-year preservation process, “we still had to find the money to make the movie.”

They eventually found that funding, and a touching, profound and inspiring film bloomed into existence as the Vault gradually gave up its secrets. Bookended by Frank’s 1991 visit to Prague, where he helped celebrate the Velvet Revolution with Havel and company, ZAPPA properly begins with a bang. Frank, via voiceover, recalls his youthful fascination with explosives as editor Mike Nichols weaves together a rich, dizzying montage of surreal ephemera and home movies from Frank’s Baltimore childhood. It’s a thrill to see Frank directing his younger siblings in an eight-millimeter kitchen zombie spectacular; you’ll gasp at his precocious adolescent editing skills, such as when he inserts Godzilla footage into his Sicilian parents’ 1939 wedding film.

“I’m a sucker for the stuff about the family,” admits Ahmet, who discovered his own trove of previously unseen home movies in the Vault. (Mugging for the camera as a child, he resembles a baby Michael Cera.) Frank died while Ahmet was still a teenager, and he becomes emotional while expressing his gratitude to the fans on Kickstarter who brought these rare examples of Zappa family togetherness—his father often being on the road or self-isolated with work—back into his life.

Gail approved Winter’s proposed film in June 2015, after which he interviewed her extensively at his own expense. In early October of that year, she died of lung cancer after a long illness. “One thing I’m very clear about is I married a composer,” Gail explains in the movie’s only interview with an immediate family member. And to be an American composer, both she and Frank will emphasize, virtually guarantees an intimate relationship with failure.

Frank Zappa’s story is not a predictable arc of youthful talent and enthusiasm blossoming into commercial success and critical acclaim followed by a long, boring afterlife. Frank began composing as a teenager after hearing the rhythmically iconoclastic sounds of Edgard Varèse, and well before picking up a guitar. In 1965, he formed the Mothers of Invention to support his composing habit. According to Paul McCartney, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was directly inspired by the Mothers’ debut album, Freak Out!, which would have been rock’s first double album if a different variety of freak out, Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde, hadn’t arrived a week earlier. Have I mentioned that ZAPPA devotes surprisingly little screen time to Frank onstage with his various Mothers iterations? There are snippets galore, but don’t stream this movie expecting previously unheard guitar magnificence or comedy-rock tomfoolery. Winter points out that you can easily find that sort of thing elsewhere, and that’s definitely not the crux of this cinematic biscuit. A triple-CD companion soundtrack, meanwhile, delivers oodles of complete tracks along with composer John Frizzell’s unexpectedly discreet and complementary score for the film.

That said, Winter has unearthed the Holy Grail of Mothers lore, albeit in miniature. In 1966, the Mothers of Invention performed six shows a week, for five months, in the 300-seat Garrick Theater above the Cafe au Go Go in Greenwich Village. Sometimes using—and often abusing—audience members who returned night after night, Frank conducted the Mothers through improvised performances that juxtaposed extemporaneous theater of the absurd with tightly rehearsed compositions.

Unfortunately, the Vault contained little that documented this watershed run. “We literally used every frame we could,” Winter says of these very special yet frustratingly few minutes. Under other circumstances, he adds, “I would have delivered a film to the Zappas and they would have asked, ‘Why did you make a three-hour film about the Garrick Theater?’ And I would have answered, ‘Because we found all the footage!’”

But ZAPPA is not a concert movie. And while Ahmet insists that Winter had “every opportunity” to use whatever live material he wanted, Frank’s onstage antics and air-sculpting guitar solos didn’t fall in line with the director and editor’s overarching narrative notion. “I felt very strongly that the film should be a story and not try to be the cinematic Wiki entry for Frank,” Winter says. “You could easily make a Ken Burns 10-part series on Zappa, but I’m not that filmmaker and don’t know who’d finance it. Maybe someone somewhere in Italy.”

Nonetheless, he says, “I am interested in doing a more expansive, virtual-reality project that would allow the possibility for a more expansive deep dive.” At which point, Ahmet, perhaps evincing some of the same techno-thusiasm that gave birth to “The Bizarre World of Frank Zappa” touring hologram show of 2019, hints that something along these lines is already underway.

***

ZAPPA is a big -hearted documentary, which is largely due to the onscreen presence of Ruth Underwood. The percussionist first caught the Mothers at the Garrick Theater and later played xylophone, marimba, vibes and other hittable objects on more than 20 Zappa/Mothers albums. In the movie, she tearfully recalls hand-delivering a letter of “love and gratitude” to Frank, whom she once considered “distant and dismissive,” during his cancer days. He gave her a hug in return.

Underwood’s dazzling rendition of Frank’s famously challenging “The Black Page #1,” with drummer Joe Travers, is one of the film’s very few more or less complete performances. In another, the Kronos Quartet run through the crepuscular None of the Above, which they commissioned from Frank but only performed once due to its difficulty. Winter says, “I reached out to Kronos [founder] Dave Harrington and his response was, ‘Yes, in a year.’ I said, ‘I guess you guys are busy, OK.’ But he was like, ‘No, it will take us a year to get good enough to play it on film.’ I called them a year later and they were like, ‘We could still use a little more time.’ But they set a date.”

ZAPPA’s finale consists of a choreographed version of “G-Spot Tornado” as performed by the Ensemble Modern at the 1992 Frankfurt Festival, where Frank’s music was featured alongside that of new-music icons John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen. “By Frank’s reckoning, it was the first time all the circumstances were designed to satisfy his creative needs, as opposed to thwarting them,” 1988 Zappa-band utility infielder Mike Keneally told me recently. The Yellow Shark, which documented this concert, turned out to be the final album Frank released during his lifetime.

“One of the movie’s many themes,” Winter says, “is this kind of gold ring he’s chasing his whole life to hear his compositions played properly.” Winter believes that it didn’t particularly vex Frank that the classical community ignored his music. “Why would he want to chase someone’s adulation? The work was more interesting than anything else, and that’s what drove him.”

***

A substantial chunk of ZAPPA is devoted to the musician’s political interventions. Frank says, early on, that “the most informative part of my political training” occurred in 1965. An undercover member of the San Bernardino Sheriff’s Department vice squad commissioned an audio porn tape for which Frank would spend 10 days of a six-month sentence in jail. Later, we see him cleaned up and besuited on Capitol Hill in 1985, speaking as “a middle-aged Italian father of four” against the infamous Parents Music Resource Center’s attempt to censor pop music. In Prague, during the Velvet Revolution, he was hailed as a symbol of Western freedom and would be named the Czech Republic’s cultural and trade representative to the United States—at least until Treasury Secretary James Baker, husband of a PMRC co-founder, said nyet.

“Frank was moved to help the Czech people preserve their music, art and national spirit,” Ahmet says. “Who helps people like that today?”

According to Winter, Zappa’s fascination with politics never flagged. “Hours and hours” of Vault tapes reportedly document Frank in his basement, quizzing experts about economics, trade and other matters. “He wasn’t vamping for an audience, or doing it for his ego,” Winter says of this unscreened material.

As for his sexual politics, ZAPPA suggests that Frank was about as woke as the next boomer guitar hero, which is to say not very. Groupie raconteuse Pamela Des Barres both dishes about Frank’s on-tour proclivities and lauds him for giving his groupie friends a voice on the wonderfully bizarre GTOs (Girls Together Outrageously) album he produced and then released on his Straight label.

But if you want to stay married to your rock star, Gail suggests, “don’t have those conversations.” Winter perceptively connects Frank’s entitled domestic arrangement with his more general disengagement with the feelings of others, including band members. In the film, Bunk Gardner attests to the disappointment that the original Mothers of Invention felt when he broke up the band in 1969. And how could they not, having basked in the intense glow of Frank’s early genius?

“I loved Zappa’s charisma, loved his eloquence, loved his ability to walk into that Senate hearing and lay waste to that whole room, just by talking,” Winter says. “But it’s not what I wanted for this movie. I wanted the guy who was insecure, quiet, afraid and joyful. I found that going back to when he was a little kid, and it was a gold mine.”

Frank may have never been more joyful than when performing, however. That’s where every part of his creative gestalt—guitarist, composer, performance artist, ringmaster—came together. “He really just enjoyed blowing people’s mind onstage,” Keneally says. “Audiences expected to have their minds completely blown, and he took it as almost a sacred duty to make sure it went down that way.”

Or, as he once said: “I am an entertainer, and it is my job to entertain you!”