Taurus "TJ" Matthews enrolled in barber school soon after graduating from Zachary High School.

A couple years later, he asked FlyBarbers owner Donald Buckles to become his mentor. Buckles agreed, and Matthews started working long hours at the new FlyBarbers location on Sherwood Forest Boulevard.

Matthews, 21, had big dreams and the work ethic to make them happen, friends and colleagues said.

But everything was cut short when he died from gunshot wounds Dec. 29. Police said Matthews and his girlfriend were cooking dinner when her jealous ex-boyfriend entered the Baker apartment, raised a silver handgun and opened fire.

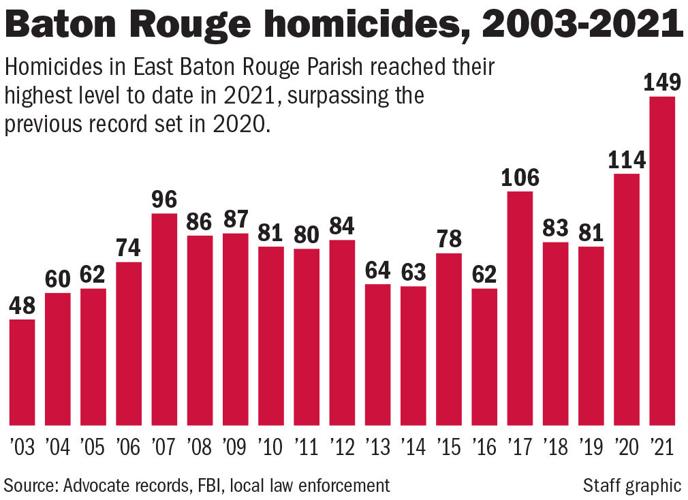

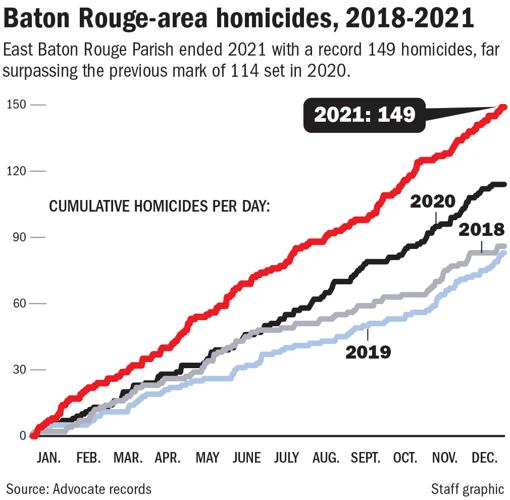

The attack marked the last homicide case of 2021 in East Baton Rouge Parish, capping off the most murderous year on record. As killings rose to an unprecedented height for the second year running, the parish marked 149 lives lost to violence, according to Advocate records.

See the toll: Here are the 149 lives Baton Rouge lost to violence.

The 149th name on a long list of victims: Taurus Matthews. Friends said he was an ambitious young man who planned to open his own barbershop, an only child whose death affirmed what his grieving mother already knew: that her son experienced tremendous love during his time on Earth.

"He was a gentle giant," said Kiawanna Moore, a close friend and coworker at FlyBarbers. She pictures Matthews driving around in his camo-wrapped Dodge Charger, blasting everything from reggae to opera to R&B. The two planned to open a recording studio in her spare bedroom.

"We had so many plans," Moore said.

Authorities are still searching for the suspected shooter, Randy Flot, 20, who faces a second-degree murder count.

The case illustrates a few trends officials have highlighted. Namely, more brazen displays of gun violence — including in broad daylight, with little regard for witnesses — and relatively minor disputes escalating into deadly gunfire, often involving young Black men.

The prevalence of domestic violence also stands out, as does an increase in retaliatory gang shootings.

These patterns took shape in early 2020 and escalated in 2021, in Baton Rouge and elsewhere, as the U.S. faced a rollercoaster of coronavirus cases and fluctuating economic restrictions, continued financial hardship, a backlogged court system, strained community-police relations following the George Floyd murder and an ever-increasing pandemic death toll.

Young father gunned down in Holiday Inn parking lot Monday morning as Baton Rouge gun violence soars

A young woman with long dreadlocks slumped against the hood of a white pickup truck in the parking lot of the Holiday Inn on Airline Highway l…

'A national issue'

After surging gun violence in 2020, Baton Rouge leaders hoped the killings would subside in 2021 along with the pandemic. But the opposite happened. January alone saw 17 homicides, making it the deadliest month of 2021.

The Advocate tracks intentional and unjustified killings, as defined by FBI crime reporting rules. Those killings are criminal homicides and legally classified as murder and manslaughter. The numbers can change if authorities deem some cases accidental or justified, and vice versa.

Other cities also saw an uptick in 2021, but the Baton Rouge spike was more dramatic than most — roughly 30% higher than the previous year and 84% higher than 2019.

"This isn't just a Baton Rouge issue, it's a national issue," said BRPD Chief Murphy Paul, who has faced criticism for failing to bring down the numbers. "I get the public frustration, but I want people to know there's a lot of work going on behind the scenes."

Paul traveled to Washington in June after the Biden administration selected 15 cities to receive federal assistance in their anti-violence efforts. Much smaller than most of the other cities, Baton Rouge received rare national attention for its rampant bloodshed.

When President Joe Biden unveiled a new plan to combat violent crime in 15 American cities and counties, including Baton Rouge, he touted the …

Nationwide, homicides rose about 4% in 2021 after a 30% jump in 2020, according to Richard Rosenfeld, criminologist and professor at the University of Missouri in St. Louis.

While the national average indicates a relatively small increase, Rosenfeld said, there are several outlier cities. For example, Austin and St. Petersburg, Florida saw massive increases, though their homicide totals remained well under 100. St. Louis, meanwhile, saw a significant drop in homicides that remains largely unexplained.

New Orleans saw a 10% increase, with 218 homicides in 2021 — the highest annual total since before Hurricane Katrina — compared to 198 in 2020.

New Orleans crime analyst Jeff Asher said he usually expects Baton Rouge to record about half as many homicides, but the 2021 total is closer to three-quarters. "That's not a good gap to be closing," he said.

After months and months of soaring gun violence in Baton Rouge, even Christmas morning brought a deadly shooting as residents of a Sherwood Me…

It appears Baton Rouge also climbed higher on the list of deadliest American cities, with a homicide rate of 52 per 100,000 residents, compared to roughly 30 per 100,000 in Chicago and 54 per 100,000 in Baltimore.

Jackson, Mississippi, a smaller city that saw 153 homicides in 2021, topped that list with nearly 100 per 100,000, according to local television station WLBT.

But overall, data from more than 20 American cities indicate the nationwide increase is tapering off, Rosenfeld said, which bodes well for 2022 — though curveballs could come from added pandemic restrictions or another egregious police brutality case.

"Barring changes on those two fronts, I think we will continue to see a slow decline across the board," he said. "But we have these cities that remain quite worrisome, including Baton Rouge. So we're far from out of the woods."

A pair of young boys ride their bikes past the scene where evidence markers remain where at least one person was shot and killed and two others were injured in a shooting on Thomas H. Delpit Drive at the A&G Grocery near Terrace Avenue Tuesday afternoon, December 14, 2021, in Baton Rouge, La.

Retaliatory violence

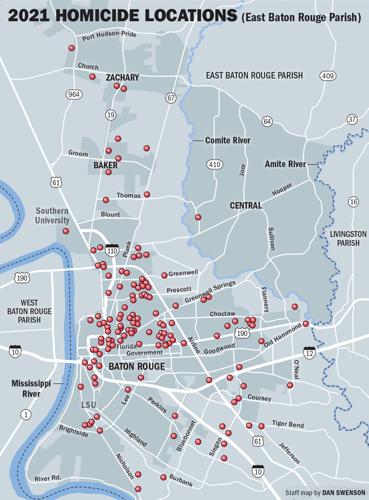

Of the 149 criminal homicides in 2021, at least 120 occurred within Baton Rouge city limits and were investigated by city police, according to Advocate records. The 70802 and 70805 ZIP codes were hit hardest, neighborhoods plagued with gun violence after decades of poverty and disinvestment.

Paul said about 96% of Baton Rouge homicide victims were Black, including justified and accidental shootings: about 86% Black males and 10% Black females. That also marks an increase from 2020, when the percentage of Black males was about 78%.

Officials said the disparity could reflect a rise in retaliatory gang shootings, many involving disputes over drug markets, gang territories and rap beefs.

After largely disbanding his narcotics division following a corruption scandal in early 2021, Paul said the remaining detectives are working with federal partners to build bigger cases against drug dealers at the highest levels of violent criminal networks. He believes those partnerships will ultimately tamp down the cycles of retaliatory violence.

Those cases often present special challenges for detectives because witnesses refuse to cooperate, preferring to take justice into their own hands.

For example, Demond Sanders was killed March 27 on North Foster Drive, about 40 minutes after he allegedly shot another man to death. Detectives believe a group of men followed Sanders and shot up his car, but detectives have not identified the suspects.

"Mothers are just crying out to other mothers to get a hold of their kids, be a loving parent and educate them about gun violence," said Liz Robinson, who founded the Baton Rouge anti-violence group CHANGE after her son was shot to death in 2018.

As usually happens when homicides spike, more East Baton Rouge cases went unsolved in 2021 than previous years: almost half. Paul said his detectives are working hard despite the crippling caseloads. Data show the national homicide clearance rate was 51% in 2020.

Jeska Carmouche was asleep when her uncle came into her room in the dark, early morning hours to relay the news: Her brother, the boy she help…

Often residents are scared to cooperate with police, said Sateria Alexander, a Baton Rouge Community Street Teams task force member. They worry for their safety and fear working with authorities puts them at higher risk of becoming victims themselves.

Paul promised increased street patrols in the most violent neighborhoods, something law-abiding residents often demand. But he said recruiting more officers into his understaffed department has been challenging.

While Baton Rouge police officers took more than 1,500 guns off the streets in 2021, Paul pointed to research suggesting a massive surge in gun sales during the pandemic could be a contributing factor in the homicide spike.

After years of worsening staffing shortages, the number of sworn officers in the Baton Rouge Police Department has fallen to its lowest point …

Pledging to take a holistic approach to fighting violent crime, East Baton Rouge Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome recently funneled $14.2 million from pandemic relief dollars into anti-violence programs. Her Safe, Hopeful, Healthy initiative, launched in mid-2020, aims to provide robust community support and interrupt cycles of violence.

"We must not operate in fear," she said. "This is a solvable problem."

Broome also called for changes to the local legal system, which remains plagued by backlogs from when the courthouse was closed for months last year: "We have to get repeat offenders off the street. We have to take a harder look at bail bonds for those accused of violence."

East Baton Rouge District Attorney Hillar Moore III agreed. He said judges have a tough job making bail decisions. Catching up on jury trials is important, he said, because "without court operations, people think they can get away with it."

When Thelma Harris bought a house in Brookstown over three decades ago, the area felt safe. Neighbors helped each other with yardwork while ch…

Surging domestic abuse

In the early weeks of the pandemic, domestic abuse advocates warned lockdown measures would take a toll on victims trapped at home with their abusers.

Their predictions came to pass, both here and across the nation. East Baton Rouge saw 36 domestic violence-related homicides in 2021, including justified killings, according to records kept by the district attorney. That number nearly doubled from 19 in 2020.

Domestic abuse reports have not drastically increased in the same timeframe, according to Melanie Fields, special prosecutor for domestic violence cases in East Baton Rouge. But she noted increasing severity of the violence described in arresting documents, from strangulation to battery of pregnant victims.

Myesha Davis had finally mustered the courage to leave her fiancé, whose increasingly controlling behavior made her rethink the relationship, …

Experts point to a multitude of factors likely contributing to the 2021 surge in south Louisiana: fatigue from the pandemic, financial hardship, childcare and education stressors, and Hurricane Ida. Advocates who identified red flags almost two years ago have grown weary watching the same grim situations play out again and again.

Fields said identifying trends in the growing number of domestic violence deaths is difficult. But one factor stands out: in most cases, law enforcement had no prior reports of abuse.

Many of the victims were young women killed by partners.

A Central woman was shot to death by her husband of eight years after an argument while at home with their three children; a man killed the mother of his child after claiming he mistook her for a burglar; a boyfriend shot his girlfriend after she admitted she was unhappy in the relationship.

But men were also victims of domestic violence killings — sometimes as collateral damage, other times as the target. Ex-husbands hunted down and killed current partners of their former wives, while teens shot men twice their age for fighting with their mothers.

There were several murder-suicides. Three children younger than 5 were killed by a parent, each time by blunt force trauma.

"For so long, domestic and dating violence were behind closed doors," Fields said. "There was a stigma. We need to erase that."

When the 3-year-old girl told relatives that her 2-year-old sister Nevaeh Allen was “in the forest,” no one knew what to make of it.

'A jungle out there'

Not long after moving his barbershop from Zachary to Sherwood Forest, Buckles saw his own family shattered by gun violence: His older brother was killed Sept. 25 in Scotlandville, their childhood neighborhood.

Cedric Clay, 41, was shot multiple times on a residential street near Greenwood Community Park — placing him among eight people killed that week alone. His case remains unsolved.

Donald Buckles, owner of FlyBarbers in Baton Rouge, cuts hair on Dec. 15. Buckles' shop is located in the Coursey/Sherwood area, which saw a big jump in diversity during the last decade, with an exodus of White people and an influx of Black and Hispanic people. Buckles' barbershop is one of many businesses in the area catering to an African-American clientele.

Buckles, a father who lives in a relatively new subdivision in the southern half of East Baton Rouge Parish, said he left Scotlandville for a reason. But it pains him to watch the historically Black community devolve into poverty and violence while majority White neighborhoods flourish. Research shows the recent nationwide homicide spike remained largely concentrated in areas where gun violence was already most common.

A few months after his brother was slain, Buckles received the news about Matthews, his star employee killed in the Dec. 29 Baker shooting.

"It's almost like a jungle out there," Buckles said. "You need certain instincts just to stay alive."

Advocate reporter Elyse Carmosino contributed to this report.

Baton Rouge Police and members of the coroner's office work the scene of a homicide, Wednesday, January 12, 2022, on Gus Young Avenue at N. Acadian Thruway in Baton Rouge, La.