As a 12-year-old in Detroit, Ben Carson asked to be baptized again. The future brain surgeon told his pastor that the first time he underwent the ritual, at age 8, he didn't yet understand what being a Christian meant.

The story of his religious background is remarkable. His single mother, forced into marriage at the age of 13 and then abandoned by her husband, learned to read in order to understand the Bible. By the time the precocious Ben was 12, he and his mother were attending a Seventh-day Adventist church.

In an interview with Newsweek earlier this year, Carson stressed his faith. "Doubt has crept out of my life over the years. Too many doors open and miraculous things have walked in."

In his 1996 autobiography, Gifted Hands (later made into a film), he writes, "Yet in looking back, I'm not sure when I actually turned to God. Or perhaps it happened so gradually that I had no awareness of the progression."

In the memoir, Carson relates his worst moral crisis. As a young teen, he lost his temper and attempted to stab a peer. He had already developed an interest in reading journals of contemporary psychology, but in this moment of self-doubt he put the secular realm aside.

"I knew that temper was a personality trait. Standard thinking in the field [of psychology] pointed out the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of modifying personality traits."

He describes himself tearfully praying to God for help in bringing his volatile emotions to heel. "Lord, despite what all the experts tell me, You can change me."

Adventist History

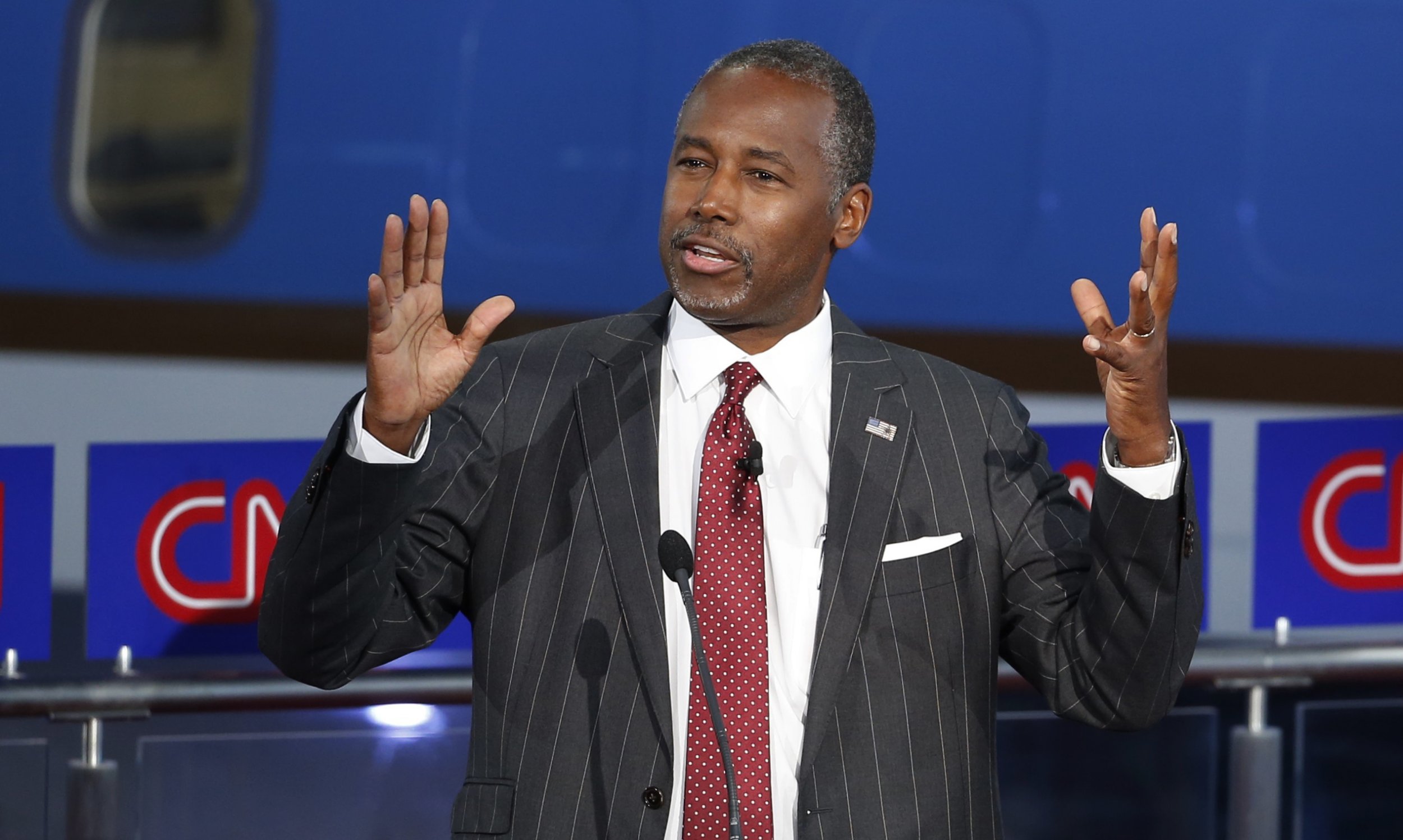

Carson's rise in the polls as he seeks the Republican presidential nomination has spurred interest in the church that has shaped so much of his life. If he continues to gain momentum, Americans are bound to have questions about the Seventh-day Adventists, just as they did about Mitt Romney's Mormon faith and, at another time, John F. Kennedy's Catholicism.

Adventists share many of the ideological tenets of evangelical Christianity. Carson the Adventist is another voice in a large field of Christian conservative presidential candidates, such as Baptists Mike Huckabee and Ted Cruz and Catholic Rick Santorum. By some estimates, there are 1.2 million Adventists in the U.S.

The Seventh-day Adventist movement emerged contemporaneously with evangelical groups during the Second Great Awakening, an American religious revival in the first half of the 19th century. Many of these movements subscribed to millennialism, the belief in an imminent second coming of Christ, which would signal the end of the world. William Miller, whose followers were known as "Millerites," predicted that the return of Jesus Christ would occur in October 1844.

When Miller turned out to be incorrect, Adventism arose as a response to what became known as "The Great Disappointment." A Millerite follower, Ellen White, claiming that she had witnessed a prophetic vision of the Ten Commandments, composed the writings that became central documents of Adventism. White wrote about the need to restore biblical purity through strengthening adherence to certain commandments, especially the observance of the Sabbath. That's why Adventists hold the Sabbath on Saturday instead of Sunday: In the original Hebrew Bible, the Sabbath is a "seventh day" observance. (In secular terms, the arrangement depends on the semantics of what constitutes the "seventh day"; i.e., whether you think the week starts on Monday or Sunday.)

"Saturday is the Sabbath," Carson says. "It was later changed by man."

"Adventism works hard to maintain a distinction between the canon of the Bible and White's writings," says David Holland, a professor at Harvard Divinity School who is writing a biography of White and Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science.

Unlike Mormons, who follow the teachings of Joseph Smith, Adventists place their modern prophet on a lower tier of religious authority than the prophets of old. Adventists also practice vegetarianism, which the church's website says is part of the virtue of a healthy life. Carson told Newsweek that he eats meat occasionally but avoids tobacco and alcohol. The church admonishes members to avoid mind-altering substances and encourages "intake of legumes, whole grains, nuts, fruits and vegetables, along with a source of vitamin B12."

As far as the apocalypse is concerned, they have not set a date.

"The standard Protestant idea is that everybody will be judged," says Holland. "The Adventist position is that judgment is taking place perpetually and that some people had already lost their chance by 1844."

This theology allows for long-term thinking. Unlike millennialists in the 19th century, Adventists have committed to permanence by building long-lasting institutions such as universities. Still, they believe that Christ's return is imminent and that it won't be subtle.

According to Holland, some scholars view Adventism and White in particular as an early source for the rise of creationism and fundamentalism in America. White was one of the first writers to advance a pseudo-geological justification for "young Earth," the belief that the Earth is only 6,000 years old. Her ideas about "young Earth" were indirectly picked up by creationists in the 1960s and '70s.

"It's hard to trace influence," says Holland. "But...she clearly is an important source of creationist fundamentalist thinking."

Carson has argued for the superiority of creationism over the theory of evolution. In an interview with Newsweek earlier this year, he distanced himself from certitude about the Earth's age. "I don't know how old the earth is and the distance between ages," he said. "There could be a billion years between ages." He has said that his beliefs about science and religion "correlate."

Does It Matter?

When it comes to political candidates, the question is always whether religion will influence governing. Romney faced those questions as a Mormon. Carson has stated that religious beliefs should not affect policy.

Holland, who teaches the history of many Christian denominations at Harvard, speaks directly about the potential influence of millennialism on policymaking. "Any suggestion that Adventist millennialism would lead to rash or irresponsible decision making is completely unsupported by the last 150 years of the movement's history," he says.

Carson has not gone about predicting the apocalypse. Former candidate Michelle Bachmann, who recently characterized the Obama administration's Iran nuclear deal as a sign of the end of times, beat him to it. Then again, Bachmann made the same claim about the president himself.

Evangelicals make up a major part of Carson's current base, as was the case with Huckabee when he won the Iowa primaries in 2008 and Bachmann when she competed there in 2012.

Carson received a round of applause in the first Republican presidential debate for declaring "there are no politically correct wars" when asked about torture. He is in the vanguard of a war on political correctness, a language-regulating movement that, in his view, also leads to the persecution of the rights of Christians.

In a presentation he gave at the Adventist Avondale Memorial Church in Australia, Carson said, "There's an agenda" in political correctness. He was referring to perceived attacks on Christians' freedom of speech and religion.

"People who read a lot know exactly what I'm talking about," he said. "If you go back and you look at the writings of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin and Saul Alinsky...they talk about how important it is to bring the U.S. into line with everybody else in order to achieve a New World Order. But in order to do that, they would have to knock down the strongest pillars: the Judeo-Christian belief system and the strong family values."

Carson has also said that gay people get more legal protection than Christians and that the experience of prison inmates demonstrates that sexual orientation is a choice. He eventually walked back the latter comment.

"I, early on, was guilty of very colorful language, and I discovered that people could not hear what I was saying, so I dialed that back," Carson told CNN's Jake Tapper in July. Back in March, Carson told Newsweek that he'd been "hyperbolic" at times and expressed regret.

"Part of the job is tone," says Carson of the presidency. "You need to be a healer and understand that if someone disagrees with you, it doesn't mean they're evil."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jack Martinez is a writer from Great Falls, Montana. He attended Stanford University, where he studied the Classics and received ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.