Transport decarbonisation – will the pandemic help us change course in time?

Over 250 people gathered together for the eighth PTRC Fireside Chat on 25 February 2021.

This was an opportunity to probe whether or not the adage ‘never let a good crisis go to waste’ would apply to the pandemic, in terms of helping us to confront the even greater crisis ahead of climate change and the imperative of decarbonising transport at pace. You can watch the full recording of the event on YouTube. As the write-up below reveals, amidst the many questions and concerns, there is a determination to change course, and change in hearts, minds and actions is happening.

Headlines

If you're in a hurry, here are the headline messages:

- A car-led recovery from the pandemic at any cost is not tenable – to achieve the level of decarbonisation needed requires a reining in of car use supported by accompanying targets.

- A green recovery meanwhile makes good environmental sense and good economic sense.

- It is reasonable to assume there will be no bounce-back for international aviation from the pandemic, reinforced by a newfound experience of business interaction through the screen rather than via time and resource hungry travel.

- There are exciting prospects of new dynamics and norms of working but it is not yet clear how these will play out – and how they do may be as much to do with power and control as with working arrangements themselves.

- Public transport, whose difficulties been exacerbated by the pandemic, needs rethinking – the operating model of fare-box reliance is broken.

- The pandemic and the associated transport measures introduced (and related communication experimented with) have helped open up an important, albeit fractious, conversation about what our streets should be for.

- Technology fix or behaviour change is a false dichotomy which creates polarisation rather than collaboration – and behaviour change concerns not only transport system users but government, industry, lobbyists – systemic behaviour change.

- There is a need to bring the post-pandemic agenda about climate change back to wellbeing and a ‘my world’ conversation that helps people identify real benefits for themselves and their families.

- Clear scientific evidence must be provided to support, and be trusted by, politicians in the glare of an unforgiving media; and news on the climate crisis and progress with tackling it must be communicated regularly to the wider public, as has been the case for the pandemic.

- Communication is much more constructive when the focus is on trade-offs and the distribution of winners and losers, rather than talking only about specific policy instruments.

- “Things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could” – this may well apply to addressing climate change and an exciting decade lies ahead, buoyed by the prospect of the Transport Decarbonisation Plan being published this Spring.

Our panel

There was another outstanding panel for this Fireside Chat comprised of: Rachel Aldred, Bob Moran, Jillian Anable, Andrew Curry, Claire Haigh and Brendan Rooney.

Setting the scene

In this 8th event in the Fireside Chat series we turned our attention to the monumental challenge of decarbonising transport as quickly as possible.

Cognitive dissonance at a personal level

This time last year I was in New York - the last time I took a carbon-hungry flight; it was just weeks before the city would bear the brunt of COVID-19 hitting the United States. It was a surreal experience. I’d paid the £39 carbon offset for my flight to ease my conscience. I walked to work that week through a bustling Time Square to the office on Broadway. Having flown across the Atlantic to talk with people about strategic planning under uncertainty, I watched the news from that office of Greta Thunberg visiting my university city of Bristol in the UK, joined by tens of thousands of adults and children in the rain, taking part in the Youth Strike for Climate event.

On the flight back I watched the documentary film called The 11th Hour. It examines how we are affecting the Earth’s ecosystems and what needs to change. At its end, my namesake Oren Lyons - a Native American Faithkeeper of the Wolf Clan – left me numb and emotional when he reflected on the havoc we have been wreaking on the planet, but ultimately on ourselves. He said:

“What if we choose to eradicate ourselves from this Earth, by whatever means? The Earth goes nowhere. … There may not be people, but the Earth will regenerate. And you know why? - Because the Earth has all the time in the world and we don't.”

The film was harrowing to watch. Worse still, it’s over 13 years old – we still seem to think we have all the time in the world.

An ideology of evil

Now I should warn you about things I more recently learnt when I watched the December 2020 annual lecture of the Global Warming Policy Foundation. It seems I may be getting, you may be getting, sucked into the relentless propaganda emanating from the ideology of climate change: an ‘ideology of evil’ no less – one reflective of the perversion of environmental science. I was warned about ‘the usual suspects’ saying that climate change could be worse than the pandemic. Local Transport Today interviewed the speaker and ran an article in February titled “Climate emergency agenda ‘regards mobility as a disease’”.

Roadmaps

So as time slips away and multiple vested and unaligned interests are at play amidst the discourses concerning climate change, what does the pandemic mean for all of this?

Earlier in the week of the Fireside Chat the UK Prime Minister set out a “roadmap to cautiously ease lockdown restrictions in England”. What a contrast with the very different type of roadmap we need to rapidly bring about systemic change in the transport sector if we are to draw down levels of greenhouse gas emissions at the pace required.

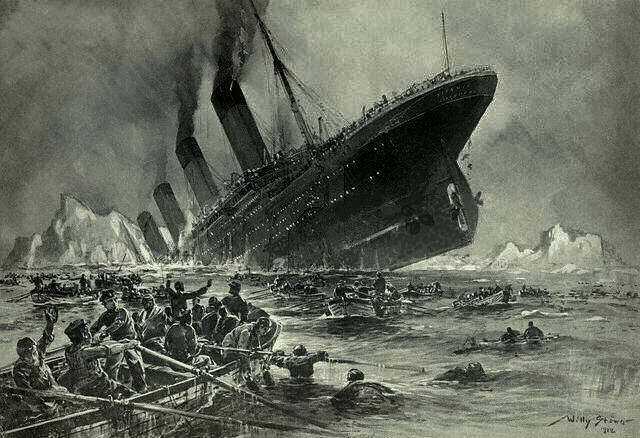

On the bridge of the Titanic

In July 2019, Professor Jillian Anable on our panel today delivered a keynote presentation to fellow academics. It had a big impact on me. It was titled “Rearranging elephants on the Titanic”. She offered a “a stark and unflinching analysis of the questions confronting the transport scientific community in the face of catastrophic climate change”. I believe the Titanic remains a very apt analogy for now considering whether the pandemic will help or hinder transport’s decarbonisation.

After several largely unheeded warnings of danger ahead, the pandemic is the equivalent to delivering perhaps the last opportunity to the captain of the Titanic to change course before disaster strikes. Indeed, it could be seen as even forcing the ship to change course, at least temporarily.

Is the temptation to reset the course or only slightly adjust the original course and maintain speed with faith in being unsinkable, or does the precautionary principle demand that a more stark and sustained change of course is needed to avoid potential loss of life?

Friend or foe?

In the exaggerated state of flux created by the pandemic, will it be possible to bring about the energy transition required in the transport sector across multiple modes and tens of millions of vehicles, including putting in place clean energy production and distribution infrastructure?

Has our collective state of incarceration over many months, imposed by social distancing, helped us to appreciate our capacity to adapt to changing circumstances and to see the scope for new behaviours that tread more lightly?

Or are the economy, livelihoods and people’s mental health so battered that we will crave our old freedoms and resent any government looking to bring about uncomfortable, even if manageable, change? Perhaps a clue is in the overnight surge in flight bookings for foreign holidays following the PM’s roadmap announcement?

Are we going to let a good crisis go to waste? Has the pandemic helped in getting powerful players and influencers to pull in a new positive and bold direction of green recovery? Or are we destined to see squabbling, struggling, provaracating and procrastinating in the ironic cause of self-preservation?

And what of COP26 in Glasgow in less than 10 months’ time? Is this perhaps the last chance to change the ship’s direction?

Many questions and fewer answers. Could our panel help?

Six views over the horizon

Each of the panellists began with a set of opening remarks.

Biting the bullet of reducing car use

Jillian was concerned about the prospect ahead of economic recovery at any cost, especially if a ‘green’ recovery is car-led with interest in easing the burden of motorists. She was alarmed by recent commentary pointing to aviation having led us out of previous recessions, implying the small proportion of people responsible for the majority of flights were praiseworthy in relation to today’s forward look to recovery. Meanwhile, could we expect holes in public finances to diminish the prospect of carbon-intensive new infrastructure, she wondered.

Do behaviour changes associated with social distancing measures signal a prospect of further such adaptability ahead or might it mean the opposite, as referred to in the scene setting, with people resentful if their freedoms once again appearing under threat? What is to become of public transport, which was struggling even before the blow dealt it by the pandemic? Jillian is concerned about the prospect of high levels of domestic, if not international, leisure travel. Meanwhile, working from home will not be an option for everyone, but for those who do, some of the energy demands transfer to the home from the office and from the commute. Jillian has doubts about how much hope can be placed in rejuvenation of neighbourhoods and popularity of active travel as a decarbonisation route out of COVID-19. In other European countries noted for their achievements in this regard, transport sector emissions have nevertheless continued to rise because cars are not reined in and continue to grow in size.

Her plea was for greater attention to looking at the bigger picture which offers a realisation that even rapid electrification of the vehicle fleet will not get us where we need to be in time. This means that a car reduction target is also needed and she points to such a target recently set by Transport Scotland (see below). Such a target needs to have acceptance but in turn demonstrable means of achieving it.

This reminded me of a proposition I put out in October 2020 on LinkedIn:

Flight of fancy?

While some trends such as homeworking have been accelerated by the pandemic, Andrew pointed to trend reversal in aviation which, in spite of pre-pandemic expectation of substantial global growth by 2050, is currently running at levels comparable with those seen in the 1970s. He feels many people in the aviation sector are ‘whistling in the dark’ to keep their spirits up.

When it comes to decarbonisation prospects he sees “no credible way to zero emissions for long-haul aviation by 2050 outside of the completely murky world of offsetting”. As a result of the pandemic, airlines are indebted to governments and are facing an imposition of conditions on future development. He notes how the new Biden administration appears to be taking carbon taxes seriously.

Andrew sees no likelihood of a ‘bounce back’ for international aviation, with a very uneven picture of border restrictions over time. This is compounded by the most profitable part of aviation being under threat: the pandemic has reinforced a reluctance for people to travel for business ‘for the sake of it’ when digital alternatives have now been normalised. Andrew says “my own bet is that aviation is not going to come back to the kind of projection levels we saw before the pandemic”. Though he still sees it being a problem for decarbonisation where people are faced with a need or desire to fly long haul where green alternatives do not exist.

A fundamental change in how we plan for transport

Claire recognised the many questions we are now posed by a world turned upside down by the pandemic, including those related to climate change where she remarks “clearly prior to the pandemic we were way off course”. She went on to point out that “while economic shutdowns may have delivered some the sorts of levels of reductions needed, by definition they're not economically sustainable”. She is encouraged by an emboldened active travel agenda and the ease with which large parts of the economy have transitioned to digital. Yet, like Jillian, she sees a very real risk of a car led recovery just at a time when car use needs to be reduced. Such a reduction would need to be supported by a massive shift to public transport (and active travel) at a time when that sector is “on its knees” and is hardly going to be in a position to play its part.

Notwithstanding Andrew’s perspective, Claire is concerned that the dramatic reduction in flying could be short-lived, particularly without air passenger duty reform. Meanwhile she feels the pandemic has “shone a light on fundamental changes needed in how we plan for transport”. She mused over whether £27 billion invested in roads might be better spent (in part) on improved digital connectivity, while recognising the reliance on our roads for movement of goods.

She sees important lessons to be learnt from the pandemic and how we can or should be prepared for system shocks, with a need for an increased focus ahead on risk and resilience. Allied to this was the need for a whole systems approach to decarbonisation reaching beyond only transport itself and technical solutions therein. Such an approach needs to be equitable and transparent with greater emphasis being placed upon internalising the external costs of consumption behaviours – something which there may be (growing) public support for. Nevertheless, she recognised that such ambitions then collide with reality: “the fact that successive governments have failed to put a penny on the price of fuel duty for over a decade despite record low oil prices is an indication of just how difficult this is going to be”.

The climate emergency is crystalising political minds

At the end of 2020 Scotland published an update to its climate change plan – something prepared in the midst of the pandemic and covering all sectors, not just transport. Brendan noted the very stretching statutory targets in Scotland. Consideration has been given to how transport interacts with that wider agenda. One of the eye-catching commitments is to reduce car kilometres by 20% by 2030 (compared to pre-pandemic levels). Brendan points to the extent of ambition reflected in this but also notes how the global climate emergency “is crystallizing minds”. Such ambition builds upon the National Transport Strategy for Scotland with aims to reduce single occupancy car travel, encourage uptake of electric vehicles, and increase public transport use and active travel – all of which have been affected by the pandemic, leaving question marks over how behaviours will change upon emergence from the pandemic. The pandemic has prompted several initiatives in terms of reallocation of roadspace and support of remote working (including community hubs).

Looking forwards, Transport Scotland is preparing a route map to address the changes that are required and is under no illusion that there will need to be sticks as well as carrots to bring about a reduced reliance on car use. Elections are coming up, offering a reminder of political challenges – especially in a country that has a significant and dispersed rural population. The next political cycle will be key.

Taking away car priority and giving back active travel

Perhaps surprisingly, as Director of the Active Travel Academy, Rachel was “a bit nervous about claiming too much for active travel” in relation to decarbonisation, recognising that “what we need goes a long way beyond replacing five mile car trips to the supermarket with five mile bike trips to the supermarket”. She cautioned that while mode shift is often seen as the key goal of active travel, it can also be a means of increasing mobility for those with restricted mobility – thereby improving their lives without necessarily reducing carbon emissions.

This said, Rachel points to the benefits of low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs). Her research into those schemes that have been longer standing revealed that after two years there was a 6% decline in car ownership “as well as over two hours a week more active travel”. This suggests knock on effects on longer car trips where carbon effects are greater. Rachel is clear that alongside discouraging car use, active travel measures are a way of offering something in return. Pointing to an article by Oliver Wainwright published on the day of the Fireside Chat, she emphasised that alongside restrictions on car use “we need to give back informal play opportunities in local streets and the evidence shows that active travel is good not just for physical health but also well-being”.

She recognises that the challenge of achieving behaviour change is the disruption needed to bring it about, such as with LTNs, which is not immediately popular. Yet within the controversy around LTNs, she senses a positive realisation emerging of it not being fair that some people are having to put up with other people’s motor traffic: LTNs are opening up a debate around the externalities of motor vehicle travel.

A profound time to look back on

Bob wanted to begin by acknowledging the terrible time that has been faced by so many people during this pandemic and pay tribute to “all the transport heroes” keeping our travel options open to us. He sees a long shadow from the pandemic but also recognises that in an optimistic sense COVID-19 may have forced a lot of people to think about certain aspects of their lives quite differently with positive consequences. He pointed to rethinking of holidays and reimagining the high street, as examples. With regard to the latter, from both a professional and personal perspective, he senses the appeal of more space for people and a little less space for vehicles.

While reluctant to refer to social distancing restrictions as an experiment, he believes they have allowed new approaches to be tried out at scale rather than remaining only thought experiments. He points to e-scooters as one emergent example. Bob sees new approaches, irrespective of their immediate short-term effects, as collectively bringing about a new way of thinking about mobility and alternatives to getting in the car which are better for people.

As Head of Environment Strategy at the Department for Transport, Bob is at the heart of developing the Government’s Transport Decarbonisation Plan (TDP). He was keen to point to the ambition of building back better in terms of decarbonisation. “If you want to decarbonise transport then you've got to tackle emissions from cars and vans and then extend that to the rest of the vehicles”. As well as the phasing out of petrol and diesel cars being brought forwards, phasing out will be extended to trucks and, Bob says, “don't be surprised in the TDP if you see it extended to other road vehicles”.

Rather poignantly, Bob referred to climate change as “the global emergency without a vaccine”. He considers it remarkable that the TDP has been developed in the midst of the pandemic – it hasn’t dropped off the agenda but is right up there as a priority. He thinks that “in future years we will look back at this time and say, gosh, wow, that was the time that we can pinpoint when we really got to grips with climate change, the year of COP in Glasgow... the TDP was a step change, it signalled that people had got a grip and pushed through change… and you did all that at the same time as you were dealing with COVID as well”.

Superfast transport planning

It was striking in many of the remarks from the panel but also coming from the audience that what we need to be doing to decarbonise resonates strongly with what many in transport planning have spent their careers seeking to achieve. In this regard, just as we have moved from the humble 56k modem for internet access to superfast broadband, we now need to unleash superfast transport planning. This said, for all that needs to happen, I felt obliged to challenge those gathered to put themselves in the shoes of the politicians who bear the brunt of all those vested interests that are lobbying for slowing things down. I was also reminded of the saying “things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could”. Perhaps this applies to addressing climate change: we are frustrated by the immediate pace of change, yet momentum may be building such that change ahead will be more dramatic than we can currently imagine is achievable. In short, we are at the bottom of the s-curve of development and change.

It makes good business sense

Voicing encouragement to politicians, Andrew highlighted how “the whole agenda and climate around green business and green investment has changed really really radically in the last two or three years”. It’s no longer simply a cost but rather a case of not being able to afford not to embrace it – and a growing number of businesses are becoming open to new business models accordingly. With “trillions and trillions of dollars of money washing around the global economy at sub-zero interest rates looking for somewhere that who can actually get a return” this makes cold business and economic sense, regardless of views on climate change. Brendan emphasised the political appeal of economy and environment as opposed to economy versus environment.

Daily press briefings on progress with the crisis

Jillian recognised Andrew’s argument but felt it was essential to bring the science and decision making together and make charting of progress very visible to society. Comparing the daily press briefings on the pandemic, she contemplated equivalent treatment for the climate crisis with a tickertape of updates running along the bottom of news feeds and press conferences with politicians flanked by scientists. This would help foster public and business consciousness regarding action to bring about change, and related progress against the crisis. She is keen to see the opportunity seized to build visible trust between the policymakers and the evidence on climate change. Claire reflected upon both Andrew’s and Jillian’s remarks. She is concerned that the reality of building back better may not live up to the rhetoric, but recognised an important role for providing clear, quality evidence into the political process to achieve more positive effect.

This seems especially important, but I cautioned that such communication of evidence is still prone to be obscured by counter-information or misinformation. The phenomenon of anti-vaxxers has emerged in response to efforts to tackle the pandemic in spite of benefits from vaccination being scientifically supported, backed by politicians and distinctly proximate to the individuals concerned. What scope is there for an equivalent anti-decarbonisation movement, exploiting the fact that climate change is not necessarily as proximate to individuals as the pandemic has been? Bob reflected upon the political challenge played out regularly on social media of never being able to please all the people all of the time, or even all the people some of the time. He expressed concern that it seems easier for those who object to change to be able to get their voices heard than those who support it – in spite of both perspectives deserving consideration.

A decade of hope

Bob’s cause for hope was to think about the change to come in the next nine years, driven by legislation. Vehicle manufacturers are going to “finally embrace battery electric vehicles and zero emission vehicles and bring them to market and actually encourage customers to buy them”. There is going to be a rapid emerging of more and more charging points. Bob is concerned meanwhile that roll-out of such infrastructure does not lock-in car dominance in our streets. He looks to concurrent change (perhaps spurred on by the pandemic) to help preserve space for people and active travel. This is indeed a reminder of the multiplicity of changes that are taking place and which need to happen in parallel and need to be managed.

Brendan emphasised the importance of considering how changes translate across to a diverse population and into people’s everyday lives. There is a need for politicians to take the public with them (and this can be helped if there can be cross-party agreement on what the science says). He pointed to last year’s multi-topic Bill going through Parliament in Scotland (the first for many years) in which the political dialogue around a workplace parking levy had to deal with a backlash from the media, with reference to it being like ‘the poll tax on wheels’. It becomes important to be able to anchor the need for such a measure in the need to respond to the climate crisis.

Communicating change

Communication is key and I was reminded of news earlier this week of ‘outrage’ at a London Borough (Merton) introducing parking permits based upon emissions. The Sun covered the story with the headline “DRIVEN MAD Drivers’ fury at ‘gestapo’ London council charging them £690 to park outside their OWN homes on-street parking charges”. Others on social media pointed out that this amounted to paying (only) £1.89 per day for use of valuable roadspace. Messaging matters. Rachel also highlighted how the temporary measures introduced in response to social distancing have also involved experimenting with communication – new ways of engagement. Communication is challenging and may not be a natural talent for some council officers. Yet the pandemic has revealed how quite complex science can be communicated objectively and clearly to the public. She feels that “it's important to have a narrative that the data fits into, that the evidence fits into”. Such a narrative can help join together different aspects of problems and solutions – “in London people are very aware of the problems caused by car use air pollution and so on but that doesn't necessarily mean that they then draw the conclusion that we need to restrict car use”. Rachel is concerned that without such a narrative, people may struggle believe that things can change and to have faith in the steps being taken.

We returned to communication throughout the Fireside Chat and it is an issue that often arises in considering how transport planning can be made more effective. There is surely a concern that if we continue doing what we have always done (or only communicating with each other on social media), we will get what we have always got. Rachel wanted to express her sympathies for local councillors when it comes to engagement with the public on challenging agendas: “I think it's an incredibly difficult job, it's a lot of work and it's not very much money”. They won’t necessarily have a good understanding of the transport planning issues they are grappling with and need support in terms of being well-briefed to respond to criticisms.

The end of conferencing as we knew it?

Alan Stevens asked in advance of the Fireside Chat whether the ‘conference industry’ should now scale down and decarbonise by thinking online first? Claire saw the appeal of COP26 being the place to underline that international conferencing didn’t necessarily need to mean lots of long-distance travel. COVID has shown us how readily we have been able to shift this to a digital alternative. However, she saw this linking to the wider agenda of how we will work in future and in turn the implications for the future of our cities. She pointed to contrasting views being played out in the press in the week of the Fireside Chat on this matter. Some companies are drawn to efficiencies of working from home and flexibility for their staff, while others are concerned about the pressures staff have been under from remote working and the loss of sociability and creativity that the traditional workplace fosters. Claire noted the mental health impacts of changing working practices and the natural human craving for social contact. There are exciting prospects of new dynamics and norms of working but its not yet clear how these will play out. Bob could relate to the appeal of a new norm in conferencing. He recalled face-to-face conferences he has turned down in contrast to those online which he has found much easier to accommodate in his schedule: “I haven't got time at the moment to be travelling to these places and I speak as somebody who ten years ago flew two or three times - to my shame I guess - to India to talk about how we'd set up the Office for Low Emission Vehicles and to share policy. And I was only there a day on each occasion - absolutely shocking”.

Big new infrastructure as a problem or opportunity?

Bob addressed an advance question from Andrew Bosi in the audience regarding how investment in high-speed rail played into the decarbonisation agenda. He suggested two positive perspectives. One relates to the opportunities with a huge infrastructure project to develop and drive new behaviours in construction that could have wider industry benefits in terms of greener construction. The other concerns scope for modal shift, notably from domestic aviation to rail – but also scope for further shift from road freight to rail freight movement. As Bob was talking I could start to imagine future scenarios of behaviour change such as digital connectivity removing some business travellers from travelling by rail, to then be replaced by other travellers moving from road to rail and perhaps the strategic road network being used to a greater extent for freight movement as heavy goods vehicles see their direct emissions being reduced and removed. Though this would also need some new thinking on pricing – and implementation of change before the road network becomes saturated with people enjoying low-price travel in electric vehicles.

Technology fix versus behaviour change – a false dichotomy

Rachel takes issue with reference often made to technology fix versus behaviour change when it comes to the decarbonisation agenda. She sees that behaviour change can imply to “gently encourage people to do the right thing” whereas she sees it as needing to be a more systemic change that is taking place. Meanwhile technology fix can be made to feel like an instant and straightforward solution, or certainly one that is more tangible for the public to respond to when consulted. Yet delivering ‘technology fix’ calls for several policy levels to bring about the system change required – rather than new technology only “being fitted into the old problematic”. She gives the example of debates targeted at restricting the speed of e-scooters to 12 miles an hour while ignoring the prospect of technologically restricting speeds of larger vehicles. “The technological fixes that we do need require behaviour change at a whole range of levels, not just individual but also government, industry, lobbyists and so on”. She points out that, as with the public, general vague encouragement isn’t that effective in bringing about behaviour change. Rachel also saw importance in re-examining the organisation of, and behaviour within, systems of production and consumption – such as assumptions of (cheap, subsidised) access by car which have, over time, shaped such systems.

I was very taken by the importance of the false dichotomy Rachel had highlighted between technology fix and behaviour change – the very notion of one versus the other risks creating polarisation rather than collaboration. Collaboration is what is needed when addressing what is ultimately a socio-technical system.

Chattering classes

As ever with the Fireside Chat events, the participant chat bar was lively throughout. Andrew was taken by various remarks. This included the ‘elephant in the room’ relationship between transport and class. He wanted to come back to the earlier discussion about future working practices, suggesting that views from industry leaders seem often not to be about working arrangements as much as about power and control: “the companies which come out and say we're going to get everybody back in the office tend to be the most sociopathic companies in the world”. He sees a class issue in relation to city centre working with a view that office workers aren’t coming back any time soon while others will have less choice in their working practices.

Equitable access to public transport is an important underpinning of urban living going forwards and yet the pandemic has created real problems in this regard. Andrew gave the example of a strike at his local bus depot the day before because the operator is trying to cut drivers’ wages in response to depleted fare revenues and a failing business model. Yet he felt that by looking at the bigger picture it was possibly to rethink this dilemma for public transport. He gave the example of France where municipalities have more freedoms and have introduced free public transport which can be justified because of benefits in terms of social and economic participation that far outweigh the costs of running services that are free for passengers. Without such rethinking he fears we will “end up in some rather old-fashioned conversations about how do you pay for bus systems out of fares” in a post-pandemic context in which people are anxious about traveling, have been discouraged from using buses, and have less obligation to travel in the same numbers into city centres for work.

Take-away messages

Moving towards the end of the Fireside Chat, it seemed to me that the challenges (as well as opportunities) ahead were all too apparent. Each and every professional needs to continue to make best endeavours to rise to these with a hope that developments we are now looking to foster will mark the beginning of a much steeper ascent up the s-curve of development in the years ahead. Panel members were invited to offer their closing remarks (while noting that Brendan had at this point fallen victim to a technical fault).

Andrew took heart from what he sensed was a renewed focus upon wellbeing emerging from the pandemic and the opportunities for many of the measures needed to help decarbonise transport also helping to improve wellbeing. He was reminded of his time at the Henley Centre when it became clear that in considering sustainability it was important to move from a ‘the world’ and ‘our world’ lens through to a ‘my world’ lens. His takeaway is that we need to bring the post-pandemic agenda about climate change back to wellbeing and a ‘my world’ conversation that helps people “identify real benefits for themselves and their families”.

Claire’s parting thought from the Fireside Chat was an impassioned and emotive one. We have learned so much from the pandemic and we have no choice but to change in the face of the climate crisis. There are signs that change is possible and that the s-curve of change lies ahead. We each have to play our part including contributing evidence into the debate and constructively supporting the politicians who must make the difficult decisions in the glare of an unforgiving media. (I was left wondering how significant our length of restricted movement during the pandemic might prove to be in terms of professional and personal attitudes to making changes ahead.)

For Jillian the discussion had left her feeling that there could be real benefit to be found from coming together to address the challenging matter of communication. Her experience from considerable engagement with climate assemblies of late is that communication is much more constructive when the focus is on trade-offs and the distribution of winners and losers, rather than talking only about specific policy instruments. Its about articulating to people the notion of a multi-modal routemap to decarbonisation in which taking difficult decisions earlier on may prove more attractive to having to make even more difficult decisions at a later stage.

Rachel is drawn to the role the pandemic has provided in opening up the conversation, difficult though it can be, about what our streets are for.

Bob acknowledged that what needs to be achieved isn’t easy and yet takes heart from how we have collectively confronted the pandemic. Climate change is an even bigger challenge. With publication of the Transport Decarbonisation Plan anticipated in the Spring, Bob is confident it will set out steps that are needed and while it might not offer everything for everybody, he concluded “please, if we all get behind it and try and deliver it, we can actually do this”.

While it was not perhaps the expectation of the Fireside Chat to reach a conclusive answer to the question “COVID-19: Friend or foe for decarbonising transport?”, it had been a rich and diverse exchange of insights and views. A fitting conclusion came in the form of a comment from Mags in the audience (applicable to all those involved in transport decarbonisation): “Claire and all the panellists, please be encouraged you are making a difference and changes are happening, the message is getting out there - keep moving forwards towards the tipping point”.

Meanwhile in the audience…

While the panel discussion was taking place in Zoom, our audience was also very active in the YouTube chat – indeed perhaps even livelier in this event than any other. There is not space here to share all the comments but do please consider taking a look at the recording on YouTube which includes them all.

Architect & urban morphologist + transit enthusiast

3yIs there a link on YouTube with these seminars? I miss them all the time. The bliss of online fatique is love the topic, register to the event and forget. The only embryo that I see in Sweden is really accelerated electrification of the car system. I see new Teslas and elBMWs everywhere. It is seemingly most post-covid19 accepted solution = keeping both individual mobility and go green travel. The cities will have to additionally sprawl to create lockdown areas (safe gettos). There is not really enough cobalt resources to manufacture 4B cars for 8B people, but enough for 1 to 2B lucky green motorists.

Professor of Transport Futures | Director of Mechanical Engineering and Marine Technology at Newcastle University

3yThank you Glenn, I bet it was a very interesting session. We do have a unique opportunity to just to decarbonise transport but to also, in the process, rebalance once and for all how we move people ...and goods. Let’s not forget freight, particularly as those changes in attitude and working patterns are also going to fuel (pardon the pun!) online commerce and home deliveries. Human interaction with technologies and decisive action on transforming cities seem essential to put the right framework in place for successful decarbonisation interventions.

Chief Scientist: Behavioural Sciences

3yGreat summary Glenn Lyons. And could not agree more with the 'tech fix versus behaviour change false dichotomy' point. Behaviour change is an outcome first. Yes - there is a theoretical and practical approach of the same name that has grown from health psychology, but over time I expect to see technology, behavioural insights, systems-thinking and so-on be accepted into the mix of ways in which we achieve the outcome.

Experienced Technical Writer/Editor

3yBecause my first foray into decarbonized transport was sail, your image caused a disconnect for a moment. Then I realized you were invoking the Titanic....

Infrastructure development & economics, Jacobs Senior Director & Visiting Professor UWE Bristol, dog lover

3yWell done Glenn Lyons