Surgical Techniques

Options available for medial collateral reconstruction include the following:

distal advancement

proximal advancement

direct repair

augmentation

medial imbrication

Distal Advancement

This technique requires retraction of the pes mechanism (Figure 2) and dissection of the medial periosteal capsular ligamentous flap from the entire anteromedial, mid medial, and posteromedial aspect of the proximal tibia, as needed. This elevation includes the entire superficial MCL, which has been attached just under the pes anserinus (Figure 3). After placement of the total knee components and with the knee in 10° to 20° of flexion, this entire capsular-ligamentous-periosteal sleeve is pulled distally and reattached to bone, using a combination of staples, sutures and/or ligament soft-tissue washers and screws (Figure 4).

Medial ligament advancement distally of the tibia, pes tendons incised at the insertion of the tibia and retracted distally.

From Krackow KA. The Technique of Total Knee Arthroplasty. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co.: 1990, 351.

Medial capsular ligament sleeve is elevated in the subperiosteal fashion.

From Krackow KA. The Technique of Total Knee Arthroplasty. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co.: 1990, 352.

After placement of the final component, the sleeve is pulled distally and secured to the tibial bone.

From Krackow KA. The Technique of Total Knee Arthroplasty. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co.: 1990, 353.

At the medial side, the ligamentous complex has a broad, flat band with a deltoid configuration spanning from an epicenter at the femur to the broad attachment at the tibia. Adequate distal advancement requires elevation of the entire distal medial sleeve from the tibia -- superficial MCL as well as the posteromedial capsular and posterior oblique ligament, and its reattachment distally. The dissection is important, and reattachment can be technically demanding, because of the soft medial side due to the differential density of the deformity.

The senior author (K.A.K.) does not use this technique for type II deformities. Our preferred method on the medial side is proximal advancement.

Proximal Advancement on the Femur

This technique involves elevation of the medial ligamentous complex from the medial epicondyle (Figure 5). The elevated tissue includes the superior and deep MCL, and the posterior oblique complex. It represents a triangular or trapezoidal flap of the capsular ligamentous tissue, which has an apex coming from the epicondylar origin, and whose distal aspect spans to include the soft-tissue elements for the entire mid medial and posteromedial aspect of the knee.

Medial capsular ligament advancement on the femur because of the inability to achieve ligamentous stability with lateral release in valgus cases. Incision in the capsule is marked with broken lines.

From Krackow KA. The Technique of Total Knee Arthroplasty. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co.: 1990, 355.

After implantation of the total knee components, the medial soft-tissue flap is pulled tight in a proximal and slightly anterior direction. After placing a specific ligament suture,[4] the femoral attachment point is freshened (Figure 6) and the tissue is applied with a staple or ligament washer and screw (Figure 7) at the epicenter. The ligament sutures are secured proximally.

Medial capsular ligament flap has been taken down from the femur. These tissues are the superficial and deep medial collateral ligament and posterior oblique ligament.

From Krackow KA. The Technique of Total Knee Arthroplasty. St. Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co.: 1990, 356.

Two locking, looped ligament structures placed in flap have been pulled proximally. A more proximally positioned soft tissue has been elevated from the surface of the bone to make room for proximal advancement.

From Lotke PA, Garino JP. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven:1999, p.224.

Note: It is important to establish the final reattachment point at the presumed epicenter of rotation for the femoral condyle (Figure 8).

The epicenter is determined, and the flap is manipulated anteriorly and proximally to re-establish the epicenter for the soft-tissue center or screw ligament-washer combination.

From Lotke PA, Garino JP. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven:1999, p.234.

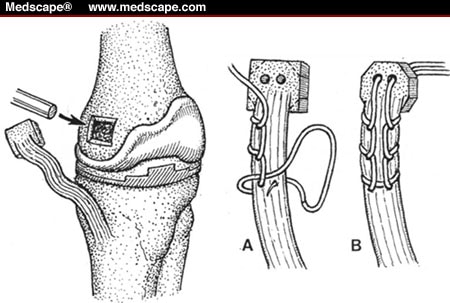

Healy and colleagues2 report favorable midterm results of another technique of proximal MCL advancement with bone plug recession. This is performed after satisfactory tibial tray placement. The attachment of the MCL at the medial epicondyle is identified, and a square bone plug is elevated, which includes the attachment of the superficial and deep MCL (Figure 9).

Attachment of the medial collateral ligament at the medial epicondyle is identified.

From Healy WL, Iorio R, Lemos DW. Medial reconstruction during total knee arthroplasty for severe valgus deformity. Clin Orthop . 1998;356:165

The epicondylar bed is prepared with a bone tamp to create a defect of 1 to 2 cm depending on the amount of ligament advancement. A #5 nonabsorbable braided suture is placed through the bony plug and woven into the MCL according to the technique described by Thomas and Jones.[4] After 2 drill holes are placed from the medial epicondylar recess, the ligament sutures are pulled through using wire pull through techniques (Figures 10 and 11). The implants are placed and the tibial base plate applied before completing reconstruction.

Elevation of the square bone plug and locked loop sutures in the medial collateral ligament.

From Lotke PA, Garino JP. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven:1999;356:166

The ligaments are pulled using the pull through technique.

From Healy WL, Iorio R, Lemos DW. Medial reconstruction during total knee arthroplasty for severe valgus deformity. Clin Orthop . 1998;356:166

Direct Repair

Direct repair of the MCL may be necessary if iatrogenic surgical injury to the midsubstance of the ligament inadvertently occurs during exposure. We prefer using a locking loop type of suture (on both sides) with a #5 Ethibond and direct repair (Figure 12).

Direct repair of the medial collateral ligament.

From Lotke PA, Garino JP. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven:1999, p. 239

Note: We prefer to protect the repair with semitendinosus augmentation, especially when there is no inherent medial lateral implant stability, (ie, minimally constrained knee arthroplasty).

Augmentation

We have used semitendinosus tendon for augmentation of medial collateral repair. Because it loses some of its initial strength in the revasculation and remodeling process, we do not believe it to be strong enough to replace the ligament but it is useful in augmentation or protection of repaired MCL.

Surgical Technique. The anterior incision of the TKA is extended slightly inferomedially to identify the tendon of the semitendinosus at the posteromedial part of the pes anserinus. Care should be taken to avoid injury to the sartorial branch of the saphenous nerve as well as the saphenous vein. This is followed by release of the proximal portion of the semitendinosus tendon from the surrounding fascia up to the musculotendinous junction with a tendon stripper and release of the proximal end of the semitendinosus tendon, which is distally. Pass a drill bit or Steinmann pin through the medial femoral condyle close to the MCL insertion, and direct it to emerge laterally. Once a satisfactory placement has been achieved, create a tunnel with a cannulated reamer. Place a nonabsorbable suture in the proximal end of the semitendinosus and pull it through the tunnel using the "homemade Chinese fingertrap" tendon passing technique, as described by Krackow and Cohn.[5] Secure this with staples in the lateral femoral epicondylar area using adequate tension with the knee in 10° to 20° of flexion (Figure 13).

Semitendinous augmentation of the medial collateral ligament repair.

From Lotke PA, Garino JP. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven:1999, pp. 239, 242, and 246

Medial Imbrication

A form of medial ligament reconstruction has been developed, referred to herein as medial imbrication. The rationale for this method comes from the following considerations:

The first is the fact that constrained intercondylar prostheses (CIPs) are only partially successful in addressing collateral ligament instability. Their success requires some measure of ligament soft-tissue sleeve balance because it is possible for the tibia to distract away from the femur in full extension or flexion, thereby causing medial instability, or worse, frank tibiofemoral dislocation. Such behavior, or the potential for it, is not usually apparent at surgery but develops later with some concomitant soft-tissue stretch. And, in some cases, a relatively small amount of plastic formation of the tibial peg can lead to later instability. Such prosthetic components, though constrained, are obviously not rigidly linked like an axle, and this dissociation possibility is an inherent property and concern.

The next consideration underlying this approach relates to the proximal fixation technique described above. It simply may not be possible with a CIP in place. The larger intracondylar housing for the stabilizer box and the presence of an intramedullary stem dictate that the space available for the screw may be minimal and possibly inadequate. Also, bone quality simply may not be appropriate. The medial bone in valgus knees may be soft.

An additional consideration is that the intracondylar housing mechanism for a CIP should be available to protect this ligament reconstruction in the early stages. The prosthetic stability is designed to prevent varus/valgus deformation, and the sutured, reconstructed, or augmented MCL element only needs to prevent straight distal or distal posterior, longitudinal type distraction and not direct valgus deformation. It would seem that during the initial 4- to 8-week postoperative rehabilitation period, the general activity level of the patient and ordinary intrinsic protective mechanisms should be sufficient to provide protection against this longitudinal distraction form of displacement. In other words, the peg is postulated to protect the imbrication early on, which then self-protects the peg later.

Surgical Technique. The superficial MCL is identified by a combination of palpation and inspection, taking into consideration the femoral epicondylar origin and the tibial attachment anterior to the posteromedial corner and deep to the pes anserinus saphenous insertion. The superficial capsule is incised longitudinally and carefully. Blunt and sharp dissection is performed at the anterior and posterior edges of the superficial MCL, and a curved plane is passed deep to the ligament at both the tibial and femoral aspects. Synovial tissue, deep MCL, and residual scar are dissected so that the plane can now be moved freely behind the superficial MCL from the femoral to the tibial regions. A single, usually #5 nonabsorbable, locking loop ligament suture is placed at the femoral side with tails pointing distally. A second, analogous suture is placed distally with the tails directed proximally. The ligament is then transected midway between the ligament sutures. The resulting ligament ends are aligned with each other, and the tying is done while the ligament is imbricated to a condition of obvious tautness, with the knee flexed at approximately 20° to 30°. The final absorbable sutures (#2 vicryl) are used to more closely approximate the overlapping ligament ends. The superficial capsular incision is closed with 2-0 absorbable sutures, and the knee is closed in the routine fashion.

Note: This technique is not recommended unless a medial lateral stabilized CIP type of component is used.

After Care

After care for MCL surgery must be customized. A number of factors must be considered, such as the quality of the repair or reconstruction, the presence and type of augmentation, type of prosthesis used (ie, constrained or nonconstrained), patient's weight, the patient's ability to cooperate in the postoperative program, and so forth.

We do seek a postoperative regimen that permits range-of-motion exercise; however, some protection and caution is required. Continuous passive motion is avoided in the earliest stage (0 to 5 postoperative days), except for patients with the medial imbrication and those having CIPs.

Proximal and Distal Advancement After Care. Patients are fit with braces close to full extension for the first 3 to 4 weeks, removing the brace frequently for specific active and active-assisted range-of-motion exercises. The splint is reapplied to protect unconscious, untoward movement and force. At 5 to 6 weeks, a long leg splint or knee immobilizer may be replaced with a hinged device, or a previously locked hinge can be unlocked. This level of bracing is maintained until 6 weeks following operation. The hinged brace is also removed for specific range-of-motion exercises and then reapplied. It is also worn at night.

At 6 weeks, a relatively simple front-laced, side-hinged knee cage is used while the patient is awake and ambulatory. This is utilized for a 6-week to 3-month period.

In the situation of an MCL repair or augmentation being protected by CIP, a more aggressive postoperative regimen can be followed.

Medial Imbrication After Care. Essentially, this is routine care with only a general warning to avoid longitudinal traction of the knee, especially traction with any mild associated valgus moments. The same is applied to a CIP type of component; it is possible to ignore the medial imbrication, and the routine postoperative program can be followed.

Medial Collateral Augmentation After Care. Spacing and movement regimens after this technique will range from what is recommended for reconstruction of the proximal distal advancement alone, at the most conservative level, to those for a medial imbrication protected by CIP at the most aggressive level. The choice depends on a surgeon's assessment of the stability at the construct and whether the prosthetic constraint, namely the presence of the CIP, can be called into play for protection.

Medscape Orthopaedics & Sports Medicine eJourn. 2000;4(4) © 2000 Medscape Portals, Inc

Cite this: Surgery of the Medial Collateral Ligament in Patients Undergoing Total Knee Replacements - Medscape - Aug 02, 2000.