Mike Brown killed Pluto. He had his reasons. But the astronomer did not set out to reclassify the solar system’s ninth planet as a dwarf. Brown was interested in the Kuiper Belt, a region of icy comets and asteroids beyond Neptune’s orbit. “I wanted to understand what was there,” Brown says. “I thought there were probably new planets still to find.”

Brown, a professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology, was correct. Analyzing images from a nearby observatory, he and his team identified a number of new Kuiper Belt Objects.

Brown found these bodies by scouring a massive number of images taken by a telescope at a nearby observatory. When comparing images from different times, a planet’s position will change from one exposure to the next. To identify objects that might be planets, Brown says, “I simply look for things that move.”

One of the Kuiper Belt Objects he identified, Eris, is the most massive celestial body found in the solar system in more than a century. Since Eris was more massive than Pluto, astronomers soon began debating what it means to be a planet, a question that astronomers had considered long settled. Pluto lost, but science won.

“The Kuiper Belt has been in a deep freeze for the past four-and-a-half billion years,” Brown says. “We are basically looking back to the earliest history of the solar system.”

Brown and Professors David Jewitt at University of California, Los Angeles, and Jane Luu at MIT Lincoln Laboratory, received the 2012 Kavli Prize in Astrophysics for their work.

Since then, Brown has discovered hundreds more Kuiper Belt Objects. “Every single time,” Brown says, “there’s this little charge of, ‘Oh my God, this little ice ball at the edge of the solar system has never before been seen by human eyes until this very moment.’ And that is always a moving experience.”

Brown is still busy investigating the outer solar system, but he managed to tear himself away to discuss the next big mysteries in our corner of the universe, including why our solar system is such an oddball, whether it might harbor extraterrestrial life, and where we might finally find Planet 9.

What makes you think there’s an undiscovered Planet 9?

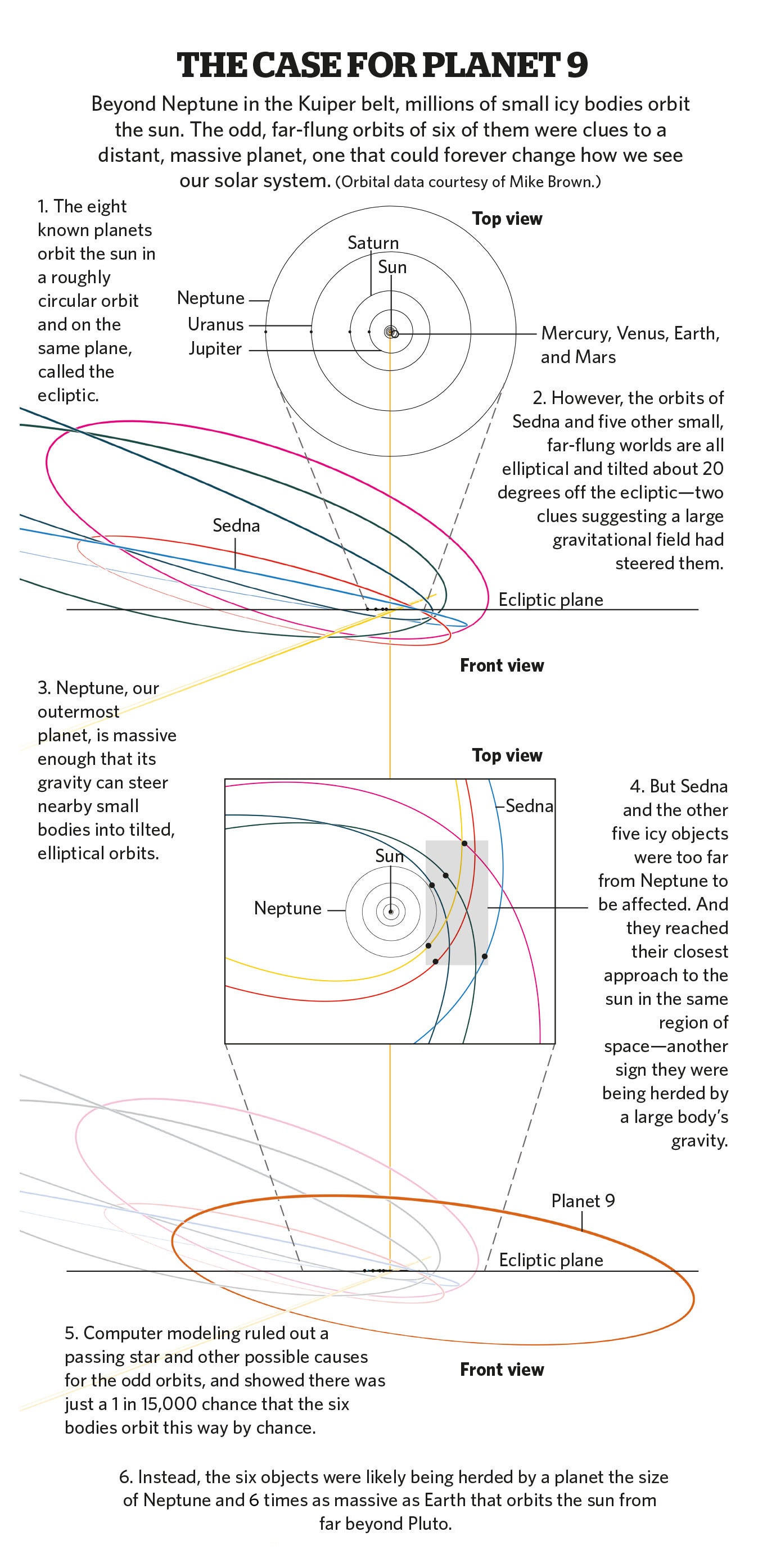

In studying the little worlds in the Kuiper Belt, we realized that their orbits are not in a random jumble. Instead, they’re all aligned—with orbits that are tilted compared to the solar system, and elongated, not circular like the orbits of other planets. When we first found this we spent a couple of years trying to convince ourselves that it was not caused by a planet. But we came to the conclusion that there’s nothing else it could possibly be. This new planet is huge—probably six times more massive than Earth—so it gravitationally dominates this vast region of space, forcing everything around it to march in line.

How will you find Planet 9?

We know it’s probably 10 to 15 times farther away than Neptune; we know how it’s tilted; and we basically know the path it travels through the sky. The one thing we don’t know is where in that path it is. But I think we now know how to go through the universe of data that exists out there, and process it in a way that we can pick out Planet 9 moving across the sky, without necessarily having to go to any telescope at all. That’s because all the planets in the solar system have been observed multiple times before they were offcially discovered. So, you can look at images that have been taken and search for objects that are over here today, but maybe three months ago had been over there, and two years earlier had been somewhere else. Then you just have to figure out how to connect those three objects out of the billions of other things around them. Computationally, it’s an incredibly intensive task, but it’s one that I think we are now finally up to.

Why look?

To me, the search for Planet 9 is the continuation of what humans have done forever. Humans explore. The first humans, I’m sure, looked across the plains and wanted to know what was on the other side. Humans crossed oceans to find what was on the other side. The solar system is in a sense the biggest neighborhood that we have. So, by exploring it, we’re making our neighborhood a little bit bigger. And once you admit the possibility of a Planet 9, and you think about how Planet 9 got there, there’s no reason to not start asking the question about Planet 10, Planet 11, Planet 12. . . .

Why is our solar system so weird?

If you had asked 20 years ago if we understood the formation of the solar system, I think most astronomers would have said that we understand it pretty well. But in the last 25 years, we have repeatedly found planetary systems around other stars that are nothing like our solar system. We find giant planets parked in orbits closer than Mercury’s orbit. We find stars with eight planets, small ones, inside Mercury’s orbit. We find all of these crazy things that we would have never predicted could be possible. We seem so different from the typical planetary system that we see out there in the galaxy.

Do you think we’ll ever encounter extraterrestrial life?

I think that the question about life elsewhere in our solar system is actually fascinating and answerable. If we could find life anywhere else in our solar system, it would be a sure-fire indicator that life is incredibly easy to start. If you have the right conditions, you have life. If we find microbial life in Europa, if we find life spewing out the vents on Enceladus, if we find hints of some sort of weird, methane-based life on Titan, then we would know that life is really easy to form—that we don’t even need the conditions we think of as habitable. That would really tell us that life is pretty much everywhere.

To hear the complete podcast with Mike Brown, watch the video below.

To learn more about brilliant work of Kavli Prize Laureates, visit The Kavli Prize. To explore more of the biggest questions in science, click here.