Reports of raptor killings soared during the U.K.'s lockdown

Conservationists allege that during the pandemic, gamekeepers on grouse shooting estates have killed many protected raptors—and that the government has turned a blind eye.

North Yorkshire — Gunshots shattered the morning stillness on Bransdale Estate, in England’s North York Moors National Park, on April 16, 2020. “It wasn’t the usual bang, bang and a pause to reload, like when men are hunting rabbits,” says a witness who asked to be identified only as Helen because she fears retaliation for speaking out about the incident. “It was six or seven shots in close succession.”

Peering through her binoculars, she says she saw a man grab something off the ground. “It was very clearly a large bird, grayish-brown in color, like a buzzard. The man disappeared behind that boulder,” she says, pointing from where she stands on a country lane toward a large rock on the far hillside. “He reappeared empty-handed. As he made his way down the crag, he was joined by a second man. They were wearing matching outfits—tweed jackets and short trousers. You could tell they were gamekeepers.”

Gamekeepers who manage wealthy estates to preserve the centuries-old tradition of grouse shooting have long been accused of illegally killing buzzards and other protected raptors. Conservationists say they kill the birds because if an aerial predator such as a hen harrier, a peregrine falcon, or an eagle soars over a grouse moor during a shoot, the grouse scatter, foiling elaborate and costly planning and disappointing clients who pay as much as $11,000 for a day of royal sport in the countryside. (Think of Lord Grantham and the Crawley men in the TV show Downton Abbey perched behind stone walls firing at birds whirring by.) What’s more, some raptors gobble the grouse. For a pair of nesting hen harriers, a grouse moor is an all-you-can-eat buffet to nourish their chicks.

Hen harriers, abundant throughout most of their range in Europe and Asia, are endangered now in the U.K., where fewer than 600 pairs remain in an area with enough natural habitat to support more than 2,600, according to bird experts. All raptors in the U.K. are protected by the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act, under which it’s illegal to intentionally kill or injure them. Nonetheless, hen harriers and other imperiled birds of prey are routinely found shot, trapped, and poisoned on or near grouse moors, including on land owned by the Crown.

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), a conservation nonprofit reports a large spike in raptor persecution in 2020 while the U.K. was locked down because of COVID-19. “In a typical year across the entire U.K., we’re looking at about 65 to 75 confirmed incidents of raptor persecution,” says Mark Thomas, head of U.K. investigations at the organization. “It doubled during the lockdown. This was a direct response of the public being removed from the countryside. People with guns who had the motive to kill birds of prey went on a killing spree. We only know about these incidents because of specific intelligence from people based in these exact areas. We suspect the total number of incidents is far greater.”

There are more birds of prey killed here than all the other counties.

Matthew Hagan, Police inspector

After a series of poisonings of rare white-tailed eagles on grouse estates in Scotland, the Scottish government signaled recently that it will implement licensing restrictions on shooting as a measure to crack down on bird crime. The government also introduced so-called “vicarious liability” legislation to hold landowners equally responsible for bird crimes committed by their gamekeepers. (Read why poison is also a threat to Africa’s wildlife.)

Thomas applauds the progress in Scotland, but he’s not optimistic that England will follow. Scotland has a more progressive government, he says, and England has members of parliament who own grouse moors. “We’ve spent 40 years on this issue, and we’ve not resolved it yet,” he says. “Amendments to the laws, increased penalties—if they even reach parliament—some of these things would be debated down because the normal response is the laws are tough enough.”

Caroline Middleton Gordon is a spokesperson for the Moorland Association, a landowner organization representing 860,000 acres of heather moorland in England and Wales, including the 18,000-acre Bransdale Estate. “The association has a policy of zero tolerance of raptor persecution,” she says. “Anyone found guilty of such a crime would be expelled.” Regarding the Bransdale incident in 2020, she says the association did a thorough investigation and no action was taken against the estate or any staff member. Moorland and other shooting organizations have pledged to report suspicious incidents involving raptors to the police immediately.

‘They cover it up’

Police investigating bird crimes say that’s an empty promise. “Hand on my heart, I have never heard of a single gamekeeper or estate owner picking up the phone or writing an email to the police, saying, I've got some information for you,” says North Yorkshire police inspector Matthew Hagen, who chairs the Raptor Persecution Priority Delivery Group, a multiagency partnership focused on prevention, enforcement, and intelligence to tackle bird crime. “They all know what is going on, and they cover it up.”

In May 2020, three gamekeepers working on Goathland Estate, part of the Queen’s lands in North Yorkshire, reportedly were suspended after an animal activist group videotaped a masked man trapping a goshawk, a threatened species. In 2007, Prince Harry was among three suspects questioned by police in relation to a raptor killing on the royal family's Sandringham Estate, in Norfolk. Birdwatchers saw two hen harriers blasted from the sky, but local investigators say the case was closed because the carcasses were never found.

“This is a peculiarly British conservation issue, deeply rooted in Britain’s class system,” says Mark Avery, former conservation director of the RSPB, co-founder of the conservation group Wild Justice, and author of the book Inglorious: Conflict in the Uplands about raptor persecution.

Researchers are using satellite-tracking devices to help document bird crimes and identify hot spots where they’re occurring. A study published in 2019 found that of 58 hen harriers tagged in the span of 10 years, 72 percent were either “confirmed to have been illegally killed or disappeared suddenly with no evidence of a tag malfunction.”

What’s more, the likelihood of harriers dying or disappearing was greater in places where land was managed for grouse shooting, including within protected areas. (Unlike in other parts of the world, the U.K.’s protected areas are based more on aesthetic value than biodiversity significance.)

Hagen says he’s “shocked and disgusted” at the level of raptor persecution happening in England. Out of about 30 dead raptors he collected in a six-month period before the pandemic, only one bird died of natural causes, and in every intentional killing, the main suspect was a gamekeeper.

The community members have nicknames for gamekeepers—Ginger Ninja, the Verminator—they suspect of being raptor killers. “There’s a saying,” Hagen says. “If it flies, it dies.” Their motivation? Keeping their jobs and the extra perks, he says. “Gamekeepers get thousands of [dollars] in cash tips over a shooting season. Some of the heaviest tippers are Middle Eastern tourists. When they finish the shooting, they sometimes give their Range Rovers and guns to the gamekeepers.”

Those who do get caught killing raptors suffer few consequences. During the past 30 years, more than 180 people in the U.K. have been convicted of killing birds of prey, largely on shooting estates. Six received jail sentences, and five of those were suspended. Scottish gamekeeper Alan Wilson, who in 2019 pleaded guilty to killing protected goshawks, buzzards, and other wildlife, was sentenced to 225 hours of community service.

Gunning for grouse

The roots of grouse shooting trace back to Balmoral Estate, in Scotland, bought in 1852 by Queen Victoria and her husband, Albert. The couple reveled in stalking the native red grouse—medium-size birds with reddish brown feathers and stubby black tails—on the estate’s moorlands, carpeted with heather, bilberry, and sphagnum. Soon, the sport became a fashionable pastime among the Victorian aristocracy.

Those who get caught killing raptors suffer few consequences.

The season opens on August 12—the “glorious twelfth”—and lasts through December 10. During those four months, the upland moors in northern England, Scotland, and Wales echo with the cracks of shotguns and the rumbles of Range Rovers scaling hillsides. There are two styles of grouse shooting. In old-fashioned “walked-up shooting,” the “guns” in their tweeds pace steadily side-by-side in a line with pointer dogs scouting in front of them. In more commercial “driven” grouse shooting, the guns stand high on the moors behind stone walls, or “butts,” firing on hundreds of grouse flushed by flag-waving “beaters” who drive the birds down the valley. When the gunfire ceases, “pickers-up” work with retriever dogs to collect the fallen quarry, often to be served at fine estate dinners. Some London restaurants celebrate the glorious twelfth with special six-course menus featuring the season’s first grouse—sometimes hustled down from the Yorkshire Dales that same day.

Each estate’s summer red grouse population varies from year to year, depending on how many birds survive the vagaries of harsh weather, disease, and predators. Gamekeepers determine if the population is substantial enough to sustain commercial shooting, and for how many days. In some years there aren’t enough birds for any shooting at all. In others, an estate may hold up to 20 shooting days or more.

A thriving hen harrier population represents a challenge for gamekeepers, partly because the birds can be polygamous. One male might have up to five female partners nesting in close proximity. Studies in the 1990s revealed that as harrier numbers grew, grouse numbers plummeted to a point where there weren’t enough to support commercial shooting.

Some recent studies have focused on finding ways for driven grouse shooting and hen harriers to coexist. One technique, called diversionary feeding, allows a licensed gamekeeper to feed a pair of nesting hen harriers a daily breakfast of domestic chicks and rats to reduce predation on the wild grouse. Some sporting estates have begun using the method, and conservationists are advocating for widespread adoption.

Another method, being tested in a five-year pilot study in North Yorkshire, is called brood management. It’s highly controversial because it aims to restrain hen harrier numbers on grouse moors. If an estate has a hen harrier nest within roughly six miles of another, the landowner can apply to have the chicks or eggs removed from it. The offspring are raised in captivity and released back into the wild after the nesting season ends.

Brood management “gives the criminals what they want,” Avery says. “To get rid of the hen harriers while not addressing the main issue—people breaking the law by killing protected wildlife.”

Wild Justice is lobbying for driven grouse shooting to be banned. They also want an end to habitat management that involves burning uplands to provide fresh green shoots of heather for young grouse because burning releases carbon, contributing to global warming, and increases the risk of wildfires and flooding in nearby communities.

Rather than a ban on driven shooting, the RSPB is calling for a licensing program under which an estate’s shooting rights would be revoked if raptors are killed. “An estate that can’t shoot can’t bring in profit,” Thomas says. “It would only take one or two prosecutions where licenses were removed to reduce raptor persecution.”

Mark Cunliffe-Lister, the Earl of Swinton, who chairs the Moorland Association’s board, says the shooting industry does a good job policing itself. We meet at Swinton Estate’s ivy-covered castle, made over as a luxury hotel and spa surrounded by 20,000 acres of picturesque countryside. From there, we drive to the top of the moor, where head gamekeeper Gary Taylor lives. Taylor offers us a cup of tea, and we take a seat at the wooden picnic table outside his stone cottage. A white horse grazes in the garden as a rooster struts about.

With red hair and a trim beard and mustache, Taylor wears a tweed flat cap, plaid shirt, wool trousers, and laced-up ankle boots. His highest priority is controlling grouse predators such as foxes, crows, and stoats. “These birds are completely wild, so it’s our job to make their life a safe one,” Taylor says. “What we’re doing is primarily for the protection of game birds, but all the other ground-nesting birds are benefiting.”

Studies show that predator control on grouse moors increases the breeding success of endangered curlews and lapwings. “The grouse shooting industry is slightly taken for granted in terms of what we’ve done for these wading birds,” Cunliffe-Lister says. “Grouse shooting had some bad times when raptors were being controlled illegally historically, but now we’re all being responsible and working a way forward, so we can still keep somebody living in this house and working up here, rather than giving up.”

Enough is enough

Satellite tracking data and stacks of police reports reveal a simple fact: Some gamekeepers are still killing hen harriers on grouse moors.

Steve Downing is a former West Yorkshire wildlife crime officer leading a team of RSPB staff and volunteers fitting hatchling hen harriers with identification bands and satellite tracking devices. I find him and two of his assistants taking stock of their gear in a parking lot at an entrance to the Forest of Bowland. Designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, Bowland is a “forest” in the medieval sense of the word: a royal hunting preserve, once brimming with boar, deer, wolves, and wildcats. The team’s mission is to climb to the top of a moor where a satellite-tagged hen harrier named Cyan is raising four chicks. At 26 days old, the biggest chick, a male, is nearly ready to fledge—the perfect age to receive his own transmitter.

“The satellite trackers tell us about their biology and how they move around, but we’re mainly doing this because they’re killed on grouse moors,” says Downing, bespectacled and wearing a camouflage baseball cap. At 71, he has the endurance of a workhorse, scaling the moors daily during the height of hen harrier nesting season from late-May to mid-July.

We tromp through heather and bracken, past countless bleating sheep, until we finally scramble over a mound of boulders and reach the bluff, buffeted by a cold wind.

Cyan isn’t happy to see us. She swoops low, chattering in alarm. We crouch in the heather, protecting our heads.

Approaching the nest, Downing and his assistant gather up the chicks two-by-two. They tuck the still flightless birds under a jacket spread on the ground to help keep them calm. Each chick is weighed, measured, cheek-swabbed for a DNA sample, and fitted with a numbered anklet and a color band to help biologists identify the birds and track their migrations.

The male chick is also outfitted with a special backpack-like harness with a $5,000 solar-powered tracking device that will report his location, elevation, acceleration, temperature, and heart rate to a satellite at regular intervals throughout the day for the next few years. “This one will be called Orion,” Downing says.

Teammate Neil Morgan is a retired infantry soldier. His T-shirt has the names of more than two dozen hen harriers that have been satellite tagged in recent years. Lined up under the words “Enough Is Enough” are eight rows of crossed-out names: Sky, Chance, Hope, Blue, Bonny, Lad, among others. “These are some of the ones we’ve lost," he says. I count 27 names in all, not even half the tagged birds that have fallen during the decade ending in 2019.

Tagged birds do die of natural causes, but all too often, Downing says, a satellite transmitter found on a dead bird has helped document a crime. Outfitted with a transmitter in 2011, a bird named Bowland Betty fledged from the Forest of Bowland and wandered all over Scotland before coming back to the North Yorkshire Dales in May 2012. A month later, her satellite data indicated that she’d stopped moving.

This is a peculiarly British conservation issue, deeply rooted in Britain’s class system.

Mark Avery, Former conservation director of the RSPB

When Bowland Betty was found on Swinton Estate in early July, a postmortem examination revealed a fragment of lead near a fracture in her leg, confirming suspicions that she’d been shot. Still, it was impossible to determine who was the culprit, or even if she was shot on that estate, so the investigation was closed.

Six years later, the story repeated when a female hen harrier named River went offline in an area on Swinton Estate where she’d been roosting. A search party looked for her, but found nothing until five months later when her solar-powered tag suddenly released a pulse of new data, confirming that she was dead, and giving her precise location on the estate. River’s heavily decomposed carcass was found less than two-and-a-half miles from her last known location. The North Yorkshire police x-rayed River’s remains and found two pieces of lead shot. A reward was offered for any information about the shooter, but no one came forward.

Cunliffe-Lister says his estate has hosted many hen harriers over the years. “There have been two hen harriers found dead, sadly, in the last decade,” he says. (No one at the Swinton estate was charged in either case.) “Betty was confirmed shot in the leg and suspected to have died of her injuries, but she could have flown many miles to the point where she died. River’s death was inconclusive, despite being ‘confirmed shot’ by RSPB.” He theorizes that the shot found with River’s carcass may have come from a grouse that she’d eaten, or perhaps it was gathered from the ground when the forensic team collected the bird.

The Nidderdale cocktail

Police inspector Matthew Hagen worked on the River case. He says the estate’s response to River’s death illustrates why it’s so difficult to prosecute in court where a person has to be guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. “I can assure you, it’s more likely than not that River was shot on the Swinton Estate,” he says. “I just can’t prove it in court.”

In recent years, Cunliffe-Lister has been taking steps to embrace hen harriers on his property, including erecting a bird blind for visitors to view a winter roost, diversionary feeding, and working with Natural England, the government’s advising environmental agency, to implement satellite tagging and study brood management.

“They’re making the right noises at the moment because it suits them,” Hagen says, “but it wasn’t always that way.”

I join Hagen for a tour of Nidderdale, in North Yorkshire—“the number one, top-dog hot spot for raptor persecution,” he says, steering his car along a twisting country lane. “There are more birds of prey killed here than all the other counties.” The RSPB confirms that North Yorkshire holds a seven-year record for having the most raptor persecution incidents: 135 cases from 2011 to 2020. Not all the birds died; some were injured and released.

Pulling over to the side of the road, Hagen motions toward the hills and valleys. “We have all this habitat—woodlands, nesting sites for raptors, rabbits—but where are the birds of prey?” he asks, looking up at the sky. “There aren’t any. Because people have been poisoning them, shooting them, trapping them. They’re just not here.”

Hagen is on the trail of a gamekeeper he believes is using a concoction of chemicals—the Nidderdale cocktail, he calls it—to kill raptors. Postmortem examinations of dead raptors have revealed a rash of poisonings all connected to a particular chemical mix. “It’s really distinct,” Hagen says. One of the compounds is the banned farming pesticide carbofuran, a neurotoxin especially lethal to birds and other wildlife. A quarter-teaspoon can kill a 400-pound bear in minutes.

Recently, raptor killings in Nidderdale made primetime TV news when a poisoned buzzard fell into a citizen’s backyard. Then a woman’s dogs experienced convulsions after coming into contact with a poison on a moorland walk. One of the dogs died. When a local citizen organized a $5,000 reward for information about who was behind the poisonings, the windows of his candy shop were egged, and he received anonymous threatening letters pushed through the mail slot.

Hagen says he knows who the poisoner is. “We've spoken to people who go to the same pub as him, and when he’s had a few drinks, he’s bragging about how he gets away with this,” Hagen says. “He tells them the police came and raided my place, but they couldn't find anything because I have it hidden somewhere else.”

The police are limited by laws that prevent them from doing covert investigations of people killing raptors because the government considers it a low-level crime. Law enforcement often benefits from evidence passed from the RSPB’s investigations team, which does secret surveillance on the gamekeepers, collects incriminating video footage, and receives witness reports.

In April 2020, RSPB investigator Howard Jones notified North Yorkshire Police about an informant, Helen, who told him she’d heard gunfire and witnessed a gamekeeper with a dead buzzard on Bransdale Estate. A second anonymous witness reported that on the same date and time, she heard gunshots and saw two buzzards fall from the sky.

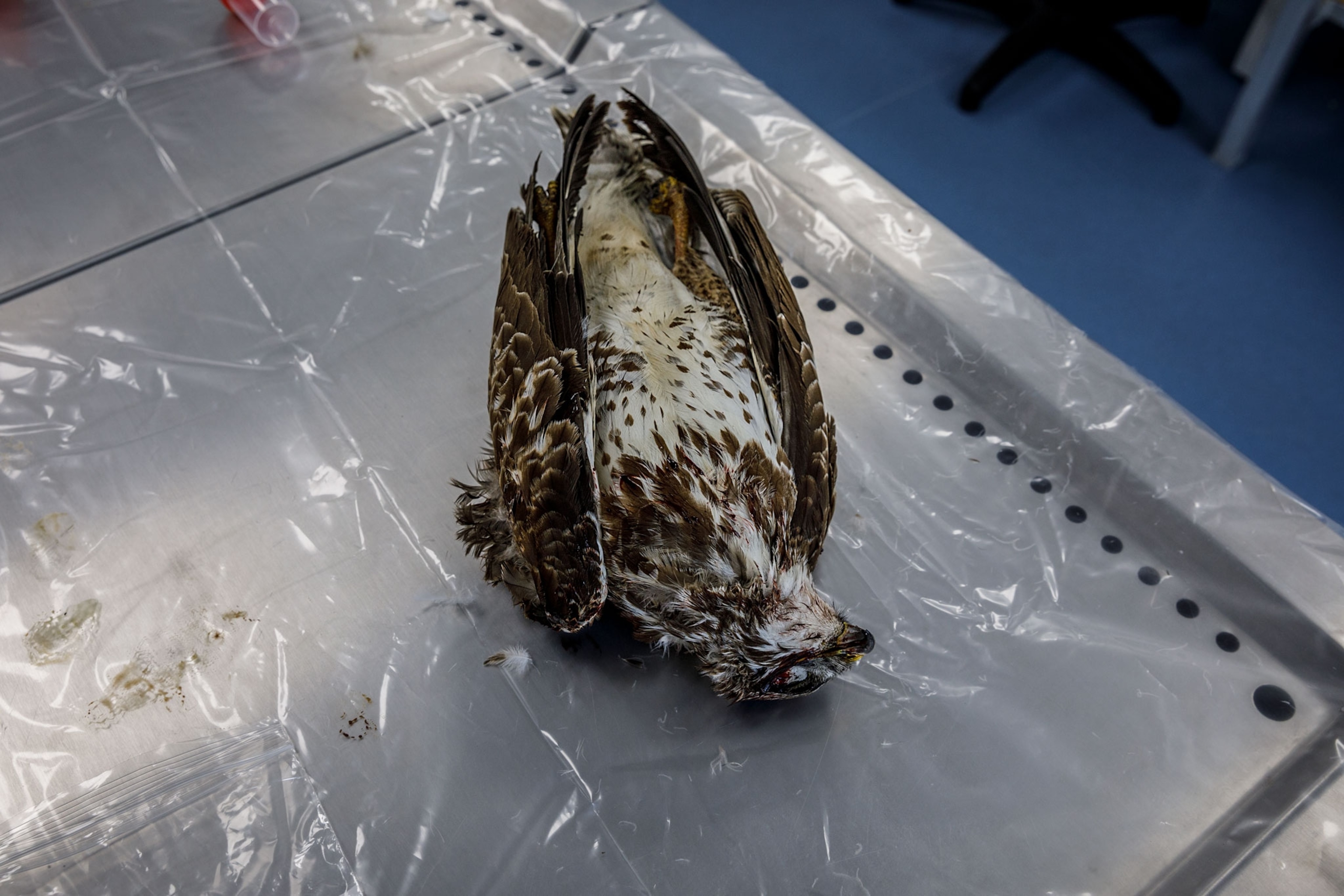

When the police went to Bransdale to investigate, Helen guided them to the area where she’d seen the person she believes was a gamekeeper. Executing a search warrant, the police found five dead buzzards stuffed in a hole in the ground. Medical examinations and x-rays of the birds’ remains revealed that they’d been shot.

“There were six gamekeepers who work on the estate,” Hagen says. “We questioned them all, and they all replied, ‘No comment.’ We know what happened, but we can’t prove it beyond a reasonable doubt, so that’s the end of it.”

Harsher sentencing might lead to better prevention of bird crimes, Hagen says, but all the police can do is gather evidence and present it to the court. For him, a conviction alone is a win for wildlife. If someone’s “found guilty, especially for an offence under the Wildlife and Countryside Act, it means that we can challenge their suitability to hold a firearm,” he says. “If they lose their gun license, they might lose their job, and their house provided with that job.”

Back at the Harrogate Police Station, where Hagen is based, he opens an evidence freezer marked “animal.” Tugging on a pair of blue latex gloves, Hagen removes a buzzard. He says a local citizen recently found the dead bird lying on a footpath. Soon it will be X-rayed, necropsied, and checked for poisons. If the bird tests positive, he’ll add it to the list of likely victims caught in the crosshairs of a gamekeeper.

This story was updated on October 28, 2021, to clarify that community members have nicknames for gamekeepers. It was also updated to include reports of raptor killings on Crown lands. It was updated on November 4, 2021, to clarify that no one at the Swinton estate has been charged with wildlife crimes related to the two hen harrier deaths in 2012 and 2018.

Wildlife Watch is an investigative reporting project between National Geographic Society and National Geographic Partners focusing on wildlife crime and exploitation. Read more Wildlife Watch stories here, and learn more about National Geographic Society’s nonprofit mission at natgeo.com/impact. Send tips, feedback, and story ideas to NGP.WildlifeWatch@natgeo.com.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

- Animals

- Feature

Octopuses have a lot of secrets. Can you guess 8 of them?

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

- Heard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followersHeard of Zoroastrianism? The religion still has fervent followers

- Strange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political dramaStrange clues in a Maya temple reveal a fiery political drama

Science

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

- The unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and MounjaroThe unexpected health benefits of Ozempic and Mounjaro

- Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.Do you have an inner monologue? Here’s what it reveals about you.

Travel

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- On the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migrationOn the path of Latin America's greatest wildlife migration

- Everything you need to know about Everglades National ParkEverything you need to know about Everglades National Park