Brutal Youth: Elvis Costello Grapples with Growing Up on His Electrifying New Record

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

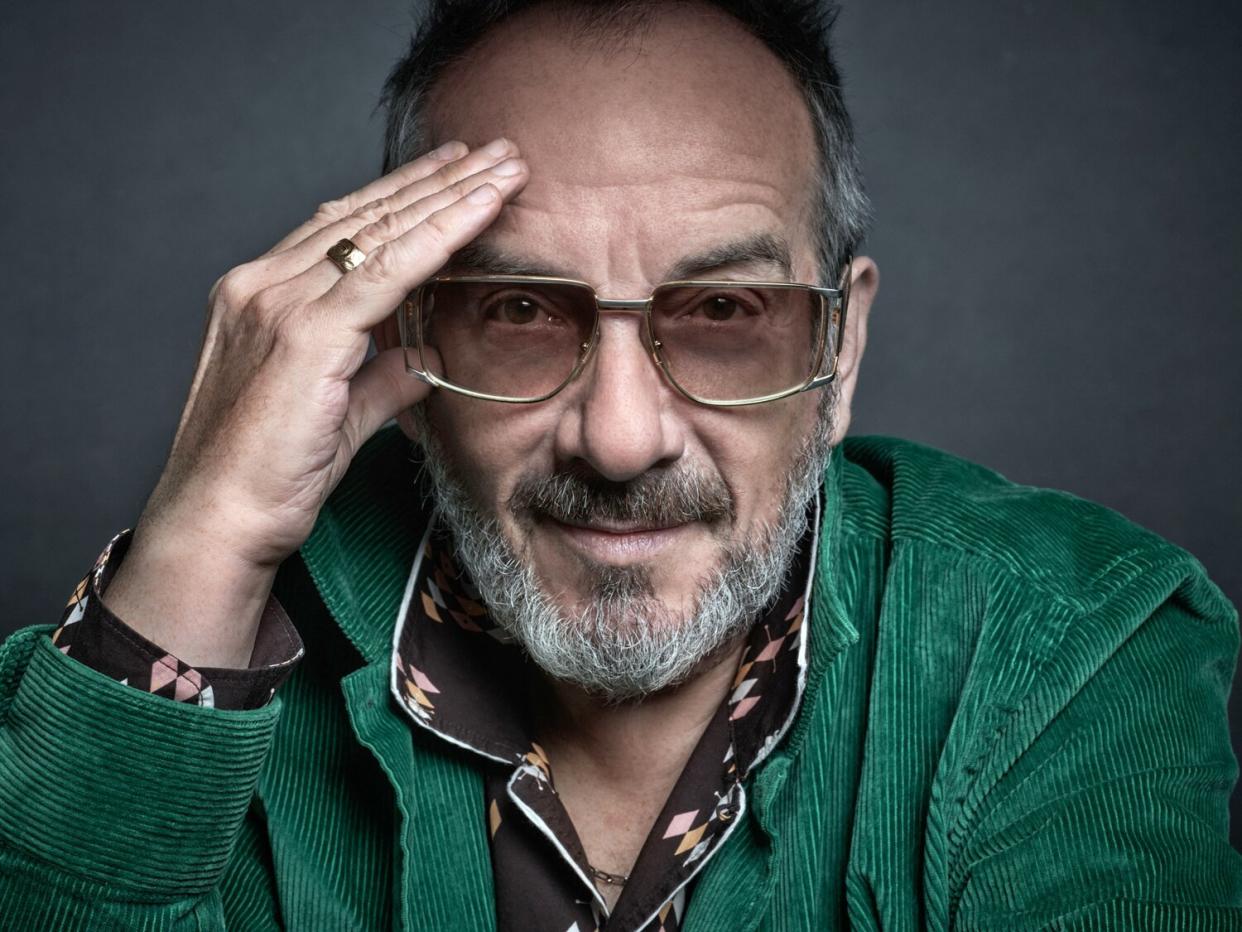

Mark Seliger Elvis Costello

Right or wrong, rock 'n' roll music — any old way you choose it — is traditionally associated with youth. So it stands to reason that Elvis Costello's most uproariously raucous album in many a year explores the tumultuous transition between adolescence and adulthood. The Boy Named If, out Friday, certainly bears a strong resemblance to the angsty-yet-articulate 22-year-old permanently etched in the grooves of his 1977 debut, My Aim Is True. But this, his 32nd disc, is far from a nostalgia trip. Rather, it's a return to the scene of the crime, the moment when one receives those grievous emotional injuries we spend the rest of our lives trying to reconcile. According to Costello, the 13 tracks "take us from the last days of a bewildered boyhood to that mortifying moment when you are told to stop acting like a child — which for most men (and perhaps a few gals too) can be any time in the next 50 years." Brutal youth, indeed.

It takes a certain amount of bravery to revisit a time in the lifecycle that most would probably rather forget. But then again, bravery is Costello's stock-in-trade as a musician. Who else would take artistic leaps as frequent and fruitful, seemingly limited only by his imagination and good taste. He's played with everyone from the Roots to the Brodsky Quartet, Allen Toussaint to Chet Baker, not to mention Marcus Mumford, Roy Orbison, Anne Sofie Von Otter, Paul McCartney, Burt Bacharach and Iggy Pop. To call Costello an artistic chameleon is putting it too simply. He's more akin to a Cheshire Cat, appearing and disappearing across the popular music spectrum at will, identifiable only by the sly grin that permeates his work.

The Boy Named If pairs him once again with the Imposters, his crack band consisting of two members of his longtime backing group the Attractions — drummer Pete Thomas, keyboardist Steve Nieve — plus bassist Davey Faragher. As with most "quarantine albums," it was recorded remotely, with the bandmates spread across Canada, France and the United States, and assembled in a piecemeal process by co-producer Sebastian Krys. But unlike most quarantine albums, it's vibrant, unified and as un-claustrophobic as a cool breeze. The tone is set with "Farewell, OK," a gleeful kiss-off bolstered by an onslaught of slashing guitar, organ stabs and thundering four-on-the-floor rhythms. The album's lead single, "Magnificent Hurt," could be a long-lost addition to the Nuggets garage rock compilation. A distant cousin of "Pump It Up," it's an obvious future classic in Costello's canon. The searing lead guitar of "What If I Can't Give You Anything But Love" is tempered with the glimmers of vulnerability found in lines like "Don't fix me with that deadly gaze/It's a little close to pity." Another highlight is the title track, an ode to a puckish invisible friend who takes the heat for our childhood misdeeds. The older we get, the less he's seen, leaving us to accept the blame alone.

It's hard to resist the urge to psychoanalyze Costello's decision to take this decidedly unsentimental look back. After all, it's common during times of mass geopolitical turmoil to derive comfort from our past and solace from the things we once loved. This current crisis finds many of us spending more time in our rooms than we have since adolescence, which no doubt provides ample time for self-reflection. In Costello's case, so did upheavals in his private life. A cross-continent move from Vancouver to New York City with his wife Diana Krall and their twin 15-year-old sons marked a major transition. A more tragic milestone was the loss of his mother last January at the age of 93. In light of such shifts, it seems only natural to retrace one's steps.

Perhaps there are clues in his two most recent projects. In September he released Spanish Model, a reimagined version of his 1978 album This Year's Model, which featured a host of Latin artists singing Spanish-language lyrics over the original backing tracks he'd recorded all those years ago. That same month, he issued the Audible Original How to Play the Guitar and Y, a joyous and hilariously idiosyncratic spoken-word treatise on the nature of music-making and creativity. Steeping himself in his early rock-centric recordings, while simultaneously rediscovering the uncomplicated joy of bashing out an elementary three-chord wonder, may well have paved the path for The Boy Named If.

Or not. Speaking about Costello in anything approaching absolutes is a mistake. Nuance is quite possibly the hallmark of his work, if one had to choose. Nothing is ever a simple declarative, be it the genre of his music or the meaning of his words. The energy of youth mixed with the wisdom accrued through Costello's 67 years of hard-won experience makes The Boy Named If a deeply thoughtful blast of rock 'n' roll, and one of the most enjoyable records he's ever produced. The album's themes contrast the most frightening elements of adolescence with the equally terrifying moments of adulthood, leaving you to figure out exactly which side of the grass is greener. Choose wisely.

In the following conversation, edited for length and clarity, Costello spoke to PEOPLE about new music, old habits, upcoming tours, and what moves him to write songs in the first place.

RELATED: Elvis Costello Is the Only Guitar Teacher You'll Ever Need

Universal Music

I got the sense that these guitar-heavy tracks are related — even just spiritually — to your recent Audible production How to Play the Guitar and Y, and also the reimagined version of This Year's Model. Is it fair to draw a line between those projects and The Boy Named If?

It wasn't conscious, but obviously a lot of things have happened that lead us here. In March 2020, we had to hurry home [from tour] as the borders were closing around us. There was all this uncertainty, fear, dread and everything that we've lived through this little while. But once home, I had the music that became Hey Clockface, I had the intention of recording the piece for Audible and we had been working on Spanish Model for a couple of years. In fact, it was ready to be released, but we had to accept that the circumstance in the economy, particularly in the countries of some of the singers who were featured, were not conducive to a new release.

So in that enforced pause, we got to work. These new songs were written close together. I guess the energy of coming off a tour [was an influence.] I'd already started off with a rock 'n' roll idea of my own in Helsinki at the beginning of 2020, where I made "No Flag" and these other songs that were kind of jaggedy. They certainly weren't the way they would've sounded with the Imposters, but once I got to work again writing, I wanted to go with major keys and a decent amount of tempo to tell a group of stories that seemed to hang together.

Diana Krall Elvis Costello

I wasn't consciously trying to pick up the energy, but I'd had the pleasure of listening to [producer] Sebastian Krys' mix of Spanish Model, which involved listening to the original instrumental tracks that we cut 43 years earlier [for This Year's Model]. When Sebastian pushed the faders up in and around these different Latin artists singing adaptations of my lyrics from all that time ago, he found all sorts of power and energy in the band. I think you'll find there are some tracks on Spanish Model where the band actually sounds more forceful [than on the original album]. We were all excited to hear what the singers brought back to us in their adaptation — bearing in mind that the three of us [in the Imposters] have been working together 44 years, on and off. It never harms to get a reminder of what it feels like to do something thrilling. Sometimes you want to concentrate on a ballad, as I did in Paris for Hey Clockface. Sometimes you want to let yourself go.

You have to let yourself not be embarrassed about rock 'n' roll. If you've been watching any of the Beatles' Get Back documentary, you see the most famous group in the world not being afraid to just sing nonsense words until the real words occur to them. There's something really endearing about watching them will those songs into existence, because it's something that I recognize — particularly in rock 'n' roll recordings. It's not that I tend to go into the studio with unfinished songs, but you're still writing them. Sometimes, in initially performing them, you don't really know how to do it. You have to let yourself go. Do you need to scream? Do you need to hold back a little bit? How is that going to affect the rhythm? There's me and [drummer] Pete [Thomas] in a dialogue. From the get-go of him and I playing together, there's been some sort of agreement between the words coming out of my mouth and his drums. That's as much the rhythm section as the actual rhythm section in some cases, because the words are coming out pretty fast. Before we knew where we were, we had a pretty solid foundation, which we then gave to Davey [Faragher] and Steve [Nieve].

It's very much a "band album." Listening to the record, it sounds like you could have all been onstage together at the Cavern or some other tiny club. It's so tight and intimate. The fact that you were, in some cases, separated by an ocean was remarkable to me. So much of rock 'n' roll is about playing as a unit and the resulting chemistry. Was that a challenge to keep the interplay going between the band despite the physical disconnect?

It really wasn't much different than people coming in and recording in separate boxes in different parts of the studio. There's a little bit of a time delay, that's all. You have to wait a day till you get the next bit, but it came. It was a puzzle that assembled itself, because we have a lot of ease and confidence in each other's judgment. I think something about not being looked at while doing it allowed us to play with maybe even more abandon than if we'd gone, "OK, we're going to go and make a record better than the other 30 we've made. Let's go!" Then you're self-conscious for a moment till you find it. In this, we had nothing to lose. What else are you going to do? Watch reruns on The Love Boat?

But I do hear what you're saying. I hear that urgency. And some of that is to do with what's going on in the compositions. I wrote them to be that way and the band didn't let me down. I think over the whole record, they get to do all of the things they're capable of.

You've said that this new record "takes us from the last days of a bewildered childhood to that mortifying moment when you're told to stop acting like a child." For most of us, that's quite a painful period. It's a time of excitement, but also a time of loss — loss of innocence, loss of a sense of certainty. What led you to revisit this time?

It just sort of came all in my mind at once. I suppose it can't be unconnected with the fact that, for the second time in my life, I had proximity to that in my home. I had less proximity when my eldest son was that age, because my career was just starting to happen then. I made choices, some of which I regret, and I missed very crucial things. Now my [younger] sons are almost 15. Until recently, we've all been in the house constantly.

Maybe also, the road ahead is shorter than the road behind. It just is.

None of the events of the last few years are far enough away to have really got into the songs through long contemplation. So just like asking me if doing Spanish Model or the Audible piece influenced the energy of this record, I can't say that the age of my younger sons, or the age of my older son, or my age, or the passing of my mother earlier this year definitively influenced the subject matter. But I don't doubt they're somewhere under the surface of all of it.

The lead single, "Magnificent Hurt" really stuck with me because it brought me back to the time of a first big heartbreak. Yet in the moment I almost enjoyed it because it was all new. There was a sense of "This is living!" Maybe it's a bit of the old writer's mentality: this'll make a good story someday. (Or perhaps I'm just a masochist.) Hearing this song, with lines like "But the pain that I felt/Lеt me know I'm alive," I got a sense that you maybe had a touch of that, too.

That song's not so specific. It's like you have such desire for somebody that it's pain; that it hurts. You have such longing. It's not really romantic, it's a carnal feeling I felt when I was that [age.] All allegiances and loyalty is lost in the moment of that thrill of desire. That's one way to say it. But it's true what you say, there's certainly moments of that. And then there's moments of fear of the unknown. You're leaving one world behind; its only certainty is that anything is possible. Your anxieties are probably just about being abandoned when you're a child. There's nothing that can stop your imagination, for better or worse, from going anywhere. So you have both dreams, fantasies, and nightmares.

Then as you become a teenager — as I recall — you become incredibly self-conscious and fearful. You feel like you're being looked at and judged when you might not be. And there's a period where other people, both other boys or sometimes girls or anybody you encounter, may have knowledge that you don't have, which makes you feel uncertain. Which is really what that song speaks of. And I tried not to point any fingers in that.

Are there any moments on the record that come to mind as being especially autobiographical?

"Penelope, Halfpenny" is sort of based on somebody I met when I was a kid. I romanticized this teacher who came briefly into our lives. It wasn't so much that she looked beautiful or that we had desires for her. She seemed to represent a series of possibilities in life that had nothing to do with learning the book we were reading. I felt like she wasn't likely to remain a teacher very long; that she was actually on her way to doing something else; maybe having a career in espionage or something. [laughs] She seemed to have a mind half out the door. And through that door, you could sort of imagine a really exciting world that grown-up people got to go. You didn't get there [in school]. There was something inherently sexy about that. Not so much the person, but what she represented: all the life that you didn't yet have any access to was thrilling. That's why I put it the way I did in the song: She "disappeared with the dot of a decimal place."

I tried to find all those little moments where you recognize that. "Mistook Me For a Friend" is about being young and reckless and completely without any compass. No moral compass, no actual compass. You're not really sure where you are, whether what's being said to you is an invitation or a threat or a seduction. Is it sincere or real, or transitory or illicit? But all of it's happening at such speed. Hence the music is more chaotic. It was fun to try and represent that rather than being actually in the moment. I've written songs when I was in that situation and they are different songs. These [songs] are not supposed to make you nostalgic for that time. This is another way to look at those moments, with maybe a little bit more of a sense of humor.

Humor and spontaneity. I was struck by what you said earlier about how "letting yourself go" is crucial to making music — specifically rock 'n' roll. That was something that you touched on in the How to Play the Guitar and Y project, too. For all of your insight and context into the historical background of music and music theory, I felt like you really respected the magic and the mystery of it all.

My way of expressing it is "keeping the inner idiot alive." Because I do think you can get over schooled in rock 'n' roll. I haven't signed up to this orthodoxy that at some point rock music got very, very successful around the mid-'70s to maybe the early '90s. There was an industry in mythology around rock — not rock 'n' roll but "rock" specifically — which leaves out a lot of other music that informs the development of it. Back in 1970, there was a festival celebrating Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard. They were seen as coming from another time, but look at the chronology: it was 10 or 15 years after they had had their first hits. It wasn't ancient history by any means!

Mark Seliger

My sons are 15 next week. I won't say who they like because next week they might not like them, but the people that they are interested in speak directly to them. If somebody likes Taylor Swift or BTS, they speak to them. And I don't see that as separate to rock. The only thing I object to about [rock devotees] is they can be quite high-handed about other forms of music. If you put orchestral strings on something, that's [seen as] sort of self-aggrandizing. If you like acoustic guitars, that's automatically put in a box and it's condescended to. Jazz is frightening to many orthodox rock people because they can't play it and they don't understand it. But that isn't a reason not to engage. It's like any kind of prejudice. It's based on ignorance and that's part of the whole sadness of this to me. Rock and roll was a subversive, revolutionary force that represented change and sex. Just like dancing and jazz. The word "jazz" was originally intended to be an insult, which is why a lot of people rightly say that's African American classical music — because that's another way to define it.

Whatever words you choose, don't let the thrill get away by being so narrow. There's a vested interest in telling this down-the-line rigid story about rhythm that hip hop subverted, R&B subverted, a lot of jazz subverted. It's why you won't see many conventional rock records in my choices, if I were to DJ for an hour. I probably would play mostly other kinds of music because [modern rock] just doesn't speak to me.

I was listening to your tour playlist that you posted online, which is certainly eclectic. I was reminded of the faux-warning label you had on [1981's album of country covers] Almost Blue: "Caution, might cause offense to narrow minds," or words to that effect.

My manager at the time thought of that as a way of teasing people, because of course it was pretty inexplicable that I like these songs as much as I did. I grew up listening to my father sing on the radio, and he sang all sorts of things from the hit parade. Good, bad or indifferent songs. I just respond to good songs, whether they're written by Rogers and Hart or Willie Dixon or Hank Williams or anybody else. There are people who wrote something great last week. I'm always hoping I'm going to hear an exciting new song, whatever style or form it takes. It can be in another language I don't even understand. But if you can sense how much it means to the person, you can respond to something in the sound of their voice.

That's kind of what I was trying to say in the Audible piece. It was trying to take away the fear of failure so you can let yourself go a bit more. When you play the guitar, it faces away from you. You can't see your own stumbles as readily as when you look down at your hands on the piano and think, "Oh, I played the wrong note." You'll hear the wrong notes, just like you'll hear the notes you're not fretting properly on guitar. But after a while it'll become fluent, and suddenly, if you start from the right place, you can master a song. And you'll be surprised how emotionally complex some of those very harmonically simple songs are. You're not just singing nursery songs. You'll be amazed to find that all of this emotion could possibly be accompanied by just three or four chord changes. The more you learn, the more you have access to more possibilities. And then it's down to your own curiosity. It's the combination of stimulating that curiosity to make yourself learn the mechanics of the instrument and also keeping that sense of play, including the foolishness. If I looked at myself doing it, I wouldn't do it. [laughs]

The jumping around looking at yourself in the mirror aspect of rock and roll — you have to keep that. I mean, look at most contemporary pop acts on a television show. What is the first thing that you notice about their demeanor? Do you know what I would say? They're quite narrow. Singers in the past, like Frank Sinatra, would put his arms out. He was small in stature and he would suddenly look imposing because he would put his arms out while he was singing and gesture in this very elegant way. But [today] you'll see even very beautiful people on television work [close]. You know why? Because they're looking at themselves on screens most of the time. They live in a kind of TikTok lens and there's nothing outside the frame. Doesn't matter if they've got dancers on either side of them. Their movements are very minute in radius. Check it out and you'll find it's true.

I'm not talking about somebody who dances everywhere on the stage. I'm talking about people who stand still and sing. They really stand still, but their faces go through a range of expressions, which are also a process of regarding yourself in the mirror. I'm not criticizing this, because we did it in a different way when I was a kid with literally anything that looked like a guitar — a big spoon or a tennis racket. People always say it's a kind of play-acting. It's an important part of doing rock 'n' roll.

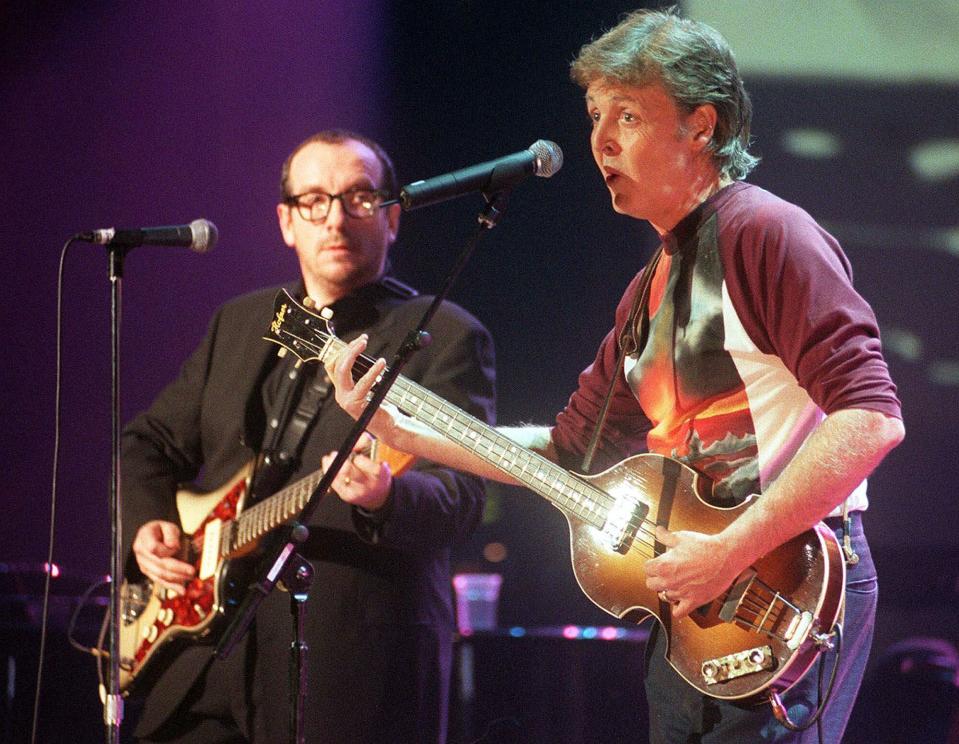

My first experiences with "performing" music involved a piece of cardboard cut to look like Paul McCartney's Hofner bass when I was 10. Years later I learned that you got your start in roughly the same way!

I did the same thing. When you're a kid, you tend to draw things that you admire. I used to draw guitars on all my school books. And then I thought, "Well, if I can draw a little one, maybe I could draw it on cardboard." It was somewhere in my kid imagination, which is a lot to do with the moment that's described in several of the songs on this record — a moment of leaving that sort of wonder. When you draw as a kid, you can draw very exceptional devices that your imagination allows you to dream of. There's no inhibition. I remember that moment where I thought, "'If I draw that guitar, then I could cut it out, I could hold it, and then I'd be Paul McCartney," or whoever.

Sean Dempsey/AP

And that is repeated with a hoop and a stick or a little wooden puppet. Today, children have the ability to go within VR or animated screens because the technology allows them to express their imagination. I was scribbling little cartoons of guitars. Now I would be able to do a three-dimensional model and 3D print it or something. There's all these options. But it's also very encouraging when somebody in the present day actually picks up a pencil and still does it the same way as would be recognized way back in antiquity. Like Leonardo da Vinci did his drawing. There are drawings of things he imagined long before they were invented by scientists. An artist imagining a device that didn't exist, that's like the childlike wonder that we get scared out of when we leave childhood into the chaos of desire and confusion and fear. Fear that other people put on you, shame that other people put on you, your own stupidity, your own mistakes, your own denial of responsibility as you become an adult.

When you're a child, you break something and — like I've said in the songs on this record — you blame it on your imaginary friend. When you get to be 25, you say, "Well, it was my other side of me that came out that made me go get drunk and sleep with that other person." Whatever transgression it is. That bad alibi isn't so charming when you're old enough to know better, is it?

Dexter MacManus Elvis Costello

On the topic of drawing and sketching — there's an 88-page book to complement the record featuring vignettes for each song, and illustrations you've done under the name Eamon Singer. Were these pictures born from the same impulse that led you to sketch in school books? How do they dovetail with the music?

The short stories have the same titles as the songs and they are the preceding scene, the succeeding scene or the background action to the song in some way. So if you have the curiosity to read it, you would find something else about that song.

I scribbled away in books, as I said, when I was a kid. But I lost the freedom to do it when I became an adult. I became too self-conscious. It's just like not being able to dance or do handstands or any things that you did with less fear when you were a child. How many adults skip? Leonard Cohen used to skip onto stage. I found it very endearing that this man, who was 80, would skip onto the stage with a joyful sort of demeanor. Even though he was thought to be very dour, he was, of course, tremendously humorous.

I had the necessity and the desire to sit in what I feared would be a vigil when my mother had a stroke in 2008. I sat in the hospital by her bed for a good few weeks waiting to see whether what the doctor said was correct or, as I suspected, that she might actually emerge with some kind of clarity and comprehension from this event. (And she did.) And the way I kept up good cheer during that upsetting time was drawing. That's the sort of time where, in other realities, you would go to the pub or drink whiskey. I didn't do that. And obviously you can't sit in a hospital ward and play the guitar. So I sat there with an iPad and drew. I didn't draw her, I didn't draw me. I drew cartoons that became illustrations. Then they became identified in my mind with songs we were playing in concert or that I was writing.

Eventually it became part of the way I thought of the music, in a dimension outside the three or four minutes of the duration of the song. These images didn't have to be the best drawings ever done in the history of art, because I wasn't putting them in a golden frame and hanging them in a gallery. I'm just putting them in juxtaposition with the music. And frankly I don't care whether everybody thinks they're any good. They came from inside my head.

It's the same as when people ask you, "Is this a very personal record?" How personal is the inside of your head? Of course it is. It doesn't all have to be a last will or confession. It doesn't have to all be a painfully rendered real-time account of your life in the previous six months or three minutes. It could be somebody else that you imagined and tried to put yourself in their shoes. In some ways that's less selfish and less self regarding. And that's why I like to sometimes write character songs to try to summon something up. It's why crime writers very rarely go to jail for killing their creations. Maybe they don't get to be God, but they get to be judge and jury. And that is acceptable. Part of the morality of writing is it's not seen as wicked.

Here's a question that's going to betray the fact that I've never written a song in my life. When speaking with people who are blessed with the ability to write, I'm always curious to know what compels them to do so. In your case, is it a desire to communicate and connect with people? Or is it a need to simply get a melody or a feeling out of you — almost like an exorcism?

I haven't really questioned it that much because I've been responding to it since I was 14 or 15. Maybe even earlier than that. I think I knew I was some kind of writer from about 9. I wasn't sure what. Not music, because I didn't play a guitar until I was 13, but I wrote songs pretty soon after I managed to stumble into a few tunes by other people. They weren't very good, but that's how you learn. But I've never really questioned why I'm doing it. I know I wasn't doing it to be famous. I did think I was going to be a songwriter, though I don't know where I thought I was going to be working. I'd read about the Brill Building and I knew about Tin Pan Alley, but I didn't know the address, so to speak. [laughs]

My first attempts to get signed professionally were as a songwriter. I didn't actually audition for record labels. I went into publishers' offices like I'd seen in the movies and made them listen to me sing. And it was pretty mortifying because I have a loud voice in a confined space and the songs were very at odds with what was in the charts then. Plus I didn't look anything like [pop stars]. It was the height of glam rock and I'd come in wearing dungarees or something. Little by little, I found somewhere to present myself, given there weren't a lot of options.

And really, even as late as '77, when I took my little home-recorded tape into Stiff Records, I still thought I was going to be hired to write songs for other people on the label. That was my stated intention. I think it was their first idea that I might write songs for Dave Edmunds, who didn't write songs. I did later write a big hit record for him ["Girls Talk"] but I think what we realized very quickly when they sent me in to demo a handful of songs was that nobody else could sing them. They were tricky in ways that weren't immediately apparent. They weren't virtuosic songs in the way that opera is virtuosic, but they were very tricky because of the way I used words in rhythm. I was the one who could render the most coherent and vivid versions of them.

For how many songs I've written, which is around 400, the amount of cover renditions is quite small. It's restricted to a handful of maybe 20 titles that have been recorded more than once. But I'm not bothered. It's worked out okay. [I've written] 15 with Paul McCartney, 30 with Burt Bacharach, my wife [Diana Krall] and a few other people, plus all the ones I wrote on my own. I'll settle for that. I can't complain about anything. I've had tremendous good fortune.

And for these new tunes, I'm very, very fortunate to work with Pete and Steve and Davey for 20 years. And Charlie Sexton — he's been playing guitar with us, and that was another benefit to our live performance. The five of us played with a different approach. Suddenly we're having different conversations. For some reason we played with more dynamic control, maybe because we were listening to the little exchanges going on. And a little change is good. A massive change maybe seems perverse, but a small change to the balance of things really made these new songs light up and actually renewed a lot of the older songs, as well. So that's good. If Charlie comes with us for a little while longer, that would be lovely. We really love playing with him. It's just changed in some very unexpected way. We hope to do that when we go back to the stage this coming year.

Given the dearth of live music, has the last two years changed your relationship to performing in any way?

I think it's really a moment where we can lose our sentimentality and our caution. I went last night to see Bob Dylan with my wife in Philadelphia. He did two songs from Rough and Rowdy Ways with such clarity. They were so vivid. I love that record, but it was as if they were 10 times more vivid than the recording. And what was more impressive and moving was that he did it repeatedly in the concert. They'd do a song that was in some way more familiar to the audience — although they were not by any means predictable choices — and then return to the repertoire from that [new] record.

It was just so inspiring. And of course, somebody coming along could say, "I wish he played this or that." But he didn't, he played these. It was uncompromising in the best way. It was with the confidence of somebody operating at the top of their powers, which is a very extraordinary thing to say when you're talking just chronologically about somebody who's 20 years past the time when some people are out in the garden digging a trench to fall into. This is vivid music being played at a high level of communication and feeling and humor. That's wonderful to have somebody you've admired a long time spur you on to hold your nerve and do the best that you can do. All the people I admire most don't compromise. And I'm sure I felt I haven't done that myself, but I know I must have done because everybody does at some point. It's not a question of laziness, it's a question of what's going to get the job done. Sometimes it's easy to throw in a song that you don't have so much feeling for, but [you know it's] one people respond to. Then you think, "Well that was too easy. Let's do something that takes us all on a little trip somewhere." And let's try and get somewhere where there's a feeling we haven't had before.