Homer Bynum’s world is full of life, even as he nears the end at 94 years old.

For 91-and-a-half years of that life, Bynum has been on the same farm, though in two different houses, at the northern-most point of Richmond County in Windblow. For those other two-and-a-half years he was in the military, island hopping through the Pacific Ocean as the coxswain driving an LST, which was to transport troops and artillery for amphibious assaults, and among the first to see combat in the invasion of Okinawa.

Bynum volunteered for service at the age of 17 and was sworn in on June 6, 1944, D-Day. He started out in the 797th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company and later he was stationed on the USS LST-817. On Easter Sunday, 1945, also April Fools Day that year, Bynum unloaded American forces and helped ferry wounded back to the hospital ship with his LST.

“You never think about getting killed when you’re over there,” he said.

As Bynum talks, you can almost see the film reels from those days pass before his eyes in their full resolution. He scoots back and forth in his wheel chair absentmindedly, as if to say that somehow, stories like his — growing up in the Great Depression, fighting in a Great War — have happy endings.

His memory of the lingo, the size of the ordinances they were equipped with, the factors at play on the battle field, remain untouched, if a little bit dusty.

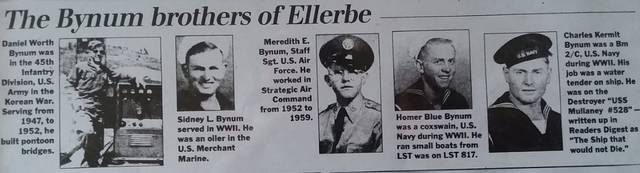

Bynum said the first dead he saw were American pilots shot down in friendly fire. His brother, Kermit — three of his brothers served in WW2 and another in Korea — was on the USS Mulaney, a new ship built after Pearl Harbor. Bynum watched a Kamikaze plane strike the Mulaney and he wouldn’t know his brother made it out alive for six months until his mother started receiving his letters again.

Miraculously, Kermit was saved because he was on kitchen duty at the time. He abandoned ship but the Mulaney didn’t explode, only caught fire, so Kermit and his crew members were able to return to it , repair it, and make it back to San Francisco. Bynum said that an article that came out after the war referred to the Mulaney as “the ship that wouldn’t die.”

Once on the island, the fighting was unlike anything they had seen because the Japanese relied on a vast network of underground tunnels the gain an advantage. Bynum said they would go three days without seeing an opposing soldier, thinking they had won, then the fighting would start all over again.

“We would measure our gains in feet and yards and get beat back and have to go again,” he recalled.

He says he still has flashbacks, in the sense of a memory breaking back into a veteran’s present day reality, but says he made it through “pretty good” compared to others. The subject of the atomic bombs strikes a nerve. Bynum said the soldiers didn’t believe the war was really going to end, dismissing talk of a nuclear punctuation mark as “scuttlebutt.”

He and his comrades were allowed to go ashore at Nagasaki two weeks after the second bomb dropped, where they would wait to be discharged. Married men with the most children got to leave first, with single men leaving last. Bynum was there for several months.

“Everything was laying flat,” he said.

They had to pack their own lunches to go ashore because the food there — if there was any — likely wasn’t safe to eat. Bynum recalled, with tears welling up in his eyes, the way the Japanese children would fight over any scrap of food the soldiers gave them or dropped.

“People were starving. If you took a sandwich and dropped a piece like that they’d fight over it,” he said. “I just gave mine to the children and went on back to the ship. I said, ‘I didn’t come over here to fight children.’ You don’t want to see nobody starve, but that’s what they were doing. They didn’t have nothing to eat.

“Every day I think about it. It’s just like the war,” he continued, describing seeing dead from both sides, shot down aircraft, and other debris floating in the water. “In order to know what it’s like you’ve got to go see it for yourself.”

Bynum will be the grand marshal for the 24th Annual Farmer’s Day Parade in Ellerbe on Nov. 24, but he’s not one for accepting any praise — he doesn’t even want a funeral, not even one with military honors. He has instead opted for he and his wife, Jean’s, ashes to be spread in forest near their house.

“I don’t have any children and everybody will have forgot about me in a year,” he said. “That’s the way things are.”

This is the second time he’s been asked to be grand marshal of the parade. The first, in 2013, was to honor him for being the oldest farmer still farming. In his life Bynum has grown cotton, wheat, peanuts and tobacco in his time. He turned down that initial offer in favor of a planned trip with Jean to Pigeon Forge in Tennessee.

Bynum’s military service made him a Shellback, a nickname given to those who cross the equator on the ocean, a rite of passage among sailors. Crossing through the time zones, he and his shipmates would gain and lose days often — “I liked when we had two Sundays in a row.”

His favorite country that he saw was the Phillipines.

“To see the moon come up in the Phillipines and them there palm trees, they bow just like the winds hitting them — it’s a pretty place,” he said.

So why stay in Richmond County all these years?

“The best people in the world live in Richmond County!” he declared, rising up out of his wheelchair. “I’ve rode up to South Dakota and all them places up there and you get out at the service station nobody speaks to you … but as soon as you cross the Mississippi River and stop at a station you talk with people. They know you. That’s the difference between a Yankee and a Southerner.”