What do you think of when you hear the term “drone delivery”? Many go right to small package delivery applications that have been making headlines for years, although those headlines are now more focused on medical supply delivery. Others go to the other end of the spectrum and consider how people themselves will be able to be delivered via “flying taxis” that will be essential elements of a UAS Traffic Management (UTM) system. Whether or not the world is ready for either type of drone operating autonomously in the airspace is a question that was explored during a recent drone delivery webinar, but one of the most salient points to come out of that conversation was around a type of delivery that could end up being a “bridge” between both of these worlds.

Ed De Reyes is the Chairman and CEO of Sabrewing Aircraft Company, Inc. His company manufacturers unmanned heavy-lift commercial cargo air vehicles that are designed to transform the way the world ships air-cargo. During the webinar, he discussed how this class of drones can fit safely into the national airspace and whether or not all of the possibilities associated with heavy-lift cargo UAVs have been fully considered. That discussion took place right after the world saw for itself what those possibilities might look during the Agility Prime Launch event when De Reyes introduced the world to the Rhaegal-A and Rhaegal-B.

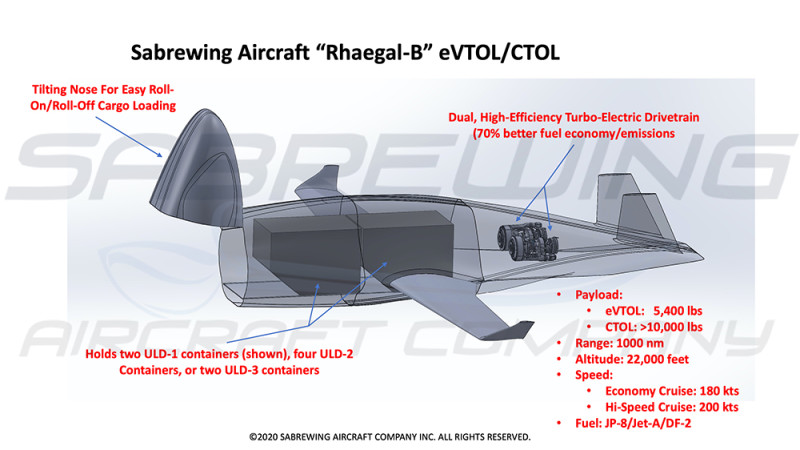

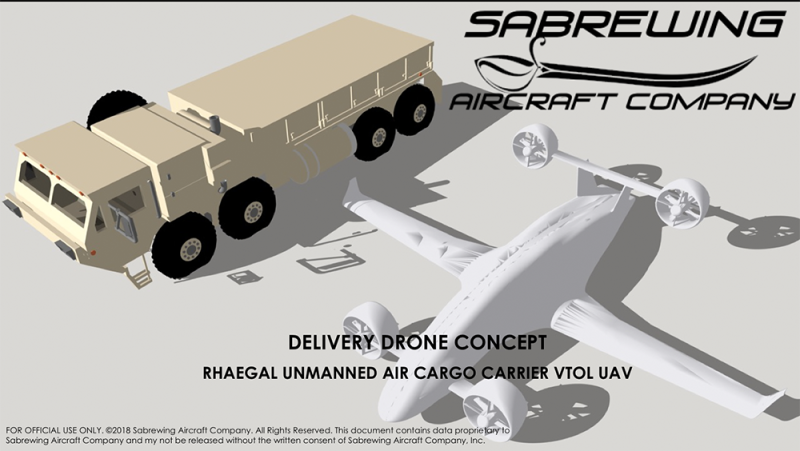

Named after an old-English word for a type of dragon, the Rhaegal is a new generation of regional cargo UAV that offers high-efficiency, all-weather operation with vertical landing and takeoff (VTOL) capabilities. In being able to carry a payload of up to 1,000 lbs over a distance of 1,000 nautical miles, the technology is poised to not only redefine cargo delivery margins, but also potentially shape how manned and unmanned aircraft can safely share the same airspace.

The Opportunities of Rhaegal-A and Rhaegal-B

The Agility Prime program is an initiative of the Air Force that is designed to accelerate the commercial market for advanced air mobility vehicles. While the “flying taxis” of UAM ecosystems are typically the sort of technology that comes to mind with that term, it also includes unmanned heavy-lift commercial cargo air vehicles exactly like the ones Sabrewing has been developing. That’s part of the reason the company became the first recipient of a contract awarded through the Air Force’s Agility Prime program.

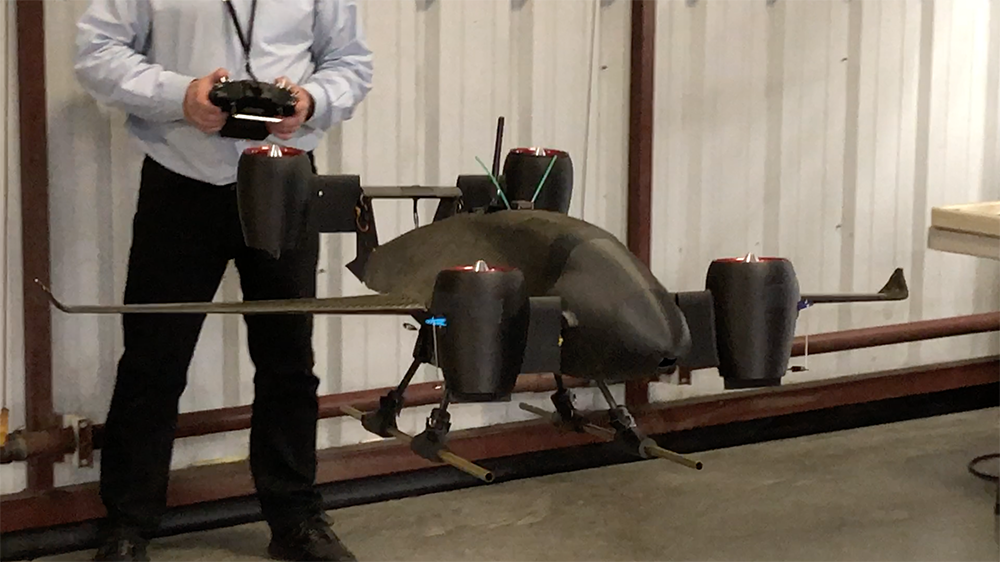

The result of this investment directly enabled the debut of the Rhaegal-A at the Agility Prime Launch event. During the event, De Reyes discussed the history and game-changing nature of his technology before revealing the Rhaegal-A, which is actually half the size of the Rhaegal-B. The Rhaegal-B can carry a much bigger payload and is larger in size overall, but the Rhaegal-A was created essentially as a proof-of-concept/flying testbed. What they wanted to show was that their model was accurate and that it can be scaled up to create true efficiencies across the cargo delivery market.

“We've been asked if we would consider going in production with the Rhaegal-A, but we really don't want to go down that path,” De Reyes said. “The Rhaegal-B does everything the Rhaegal-A does, but it does so much more and that’s really important in the cargo world, where what really matters is how much more weight you can lift and move. Commercial cargo companies make their money based on how much they can move from one place to another. With the Rhaegal-A, we’re proving we have the cargo space as well as the lifting power, all of which will be that much more powerful and viable with the Rhaegal-B.”

That recognition of what cargo companies want and need illustrates how such applications can serve as a bridge for the eventual UAM ecosystem that so many are talking about. While the excitement in UAM is real, the market is unknown. That’s not the case for cargo deliveries, which can show 100 years worth of data. Outside of the medical context, small package deliveries can struggle with costs, while the incredible projections around the UAM market are based on the automobile segment. There are assumptions and no regulation while the autonomous cargo delivery segment has both. That definition of the regulation is especially important.

Regulatory Considerations for Unmanned Operations

For as long as drone technology has been a viable commercial option, the two most important topics of conversation have been around regulation and ROI. It’s one thing to talk about how drone technology can do something in a faster, cheaper and safer manner, but regulation and ROI define how these efficiencies make business sense. Questions around the regulation of unmanned heavy-lift commercial cargo air vehicles are actually fairly simple to address since they’ve already been sorted out with FAA rules relating to manned heavy-lift commercial cargo air vehicles.

Sabrewing ensured the regulatory enforcement and regulatory considerations that a typical commercial cargo operator has to consider were taken into consideration in the development of their aircraft. They built an aircraft that will be certified to Federal Aviation Requirements (FAR) Part 23, which deals with all manned aircraft that cargo companies know and can define. Sabrewing told the FAA that they were going to build an aircraft that could be certificated by the same standards that they'd apply to manned aircraft, with the only difference being they wouldn’t actually have humans on board. The FAA has been comfortable with that approach, but it’s just one factor in terms of how cargo companies can consider such technology in the context of regulation they already know.

“Our customers typically already have a Part 135, which really is an on-demand air charter issued by the FAA,” De Reyes told Commercial UAV News. “So the aircraft itself is certificated the same way that a manned aircraft would be. Customers can rely on what they're already using and are familiar with. There are no restrictions so we’ll be able to fly our aircraft into any airspace without any kind of waivers. Some companies have received waivers under Part 107 to fly cargo along certain routes, but they can only fly that route back and forth at a certain time and in certain weather. Because a Part 23 aircraft is not restricted for use in Part 135 operations, we can do things that any regular unmanned aircraft can do. ”

Exciting as it might be to look at hardware like the Rhaegal-A, this technology is not new. That’s the reason the FAA has been so comfortable certifying it. Sabrewing is using known technologies, known instrumentation and known avionics. Reapers, Predators and Global Hawks have been flying in the National Airspace for years now and Saberwing aircraft are using those same methods and standards. Their aircraft utilize ADS-B, transponders and other elements that already exist, but they’re using these pieces with other elements of their system to provide a powerful detect and avoid solution that makes sense for an unmanned aircraft. Ultimately, that’s why the FAA looked at the Sabrewing solution and defined it as known technology, rather than something that was inherently different.

That recognition directly fueled the considerations around how the company is working to create a strong ROI for customers of all types.

What’s the ROI?

During the Agility Prime Event, De Reyes mentioned that his company talked with potential cargo customers to better understand and incorporate practical needs around things like the ability to operate in inclement weather and that their aircraft had to accommodate standard cargo containers. He also mentioned that Sabrewing commissioned an independent analysis of their engineering and design which confirmed that not only did the aircraft meet the 25 to 1 lift to drag ratio that they had touted, but could almost achieve a 27 to 1 ratio with a few small changes, which the company made.

Those efforts and results underscore conversations about ROI that De Reyes continues to hear and address. The challenges associated with those measurables relate to the newness of the technology though. Sabrewing aircraft are inherently designed to open up new operational territory, which means a company can operate in a place they cannot go right now with a helicopter or even with a fixed-wing aircraft. Sabrewing technology can operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week, so the investment can turn around very quickly. ROI all depends on how someone wants to use the aircraft, and how often they use it.

“For anyone looking at our solution, you should ask yourself whether or not you need this kind of extended delivery capability in your organization,” De Reyes mentioned. “Does it make sense for your organization to be able to take cargo to a remote location? Asking and answering that question is the first step. If the answer is yes, then it's about whether you’re planning on spending money on helicopters that are bucketed out as acquisition costs, operational costs, etc. Anyone who has those numbers can connect with us to understand our equivalent acquisition and operations costs to decide for themselves how they stack up.”

As part of that context around costs, De Reyes mentioned that the Rhaegal aircraft can be put together and taken apart as four separate pieces. That means each of these parts can be swapped out with new or inspected section and inspected individually. When a manned aircraft has to be inspected, that aircraft can be out of commission for days or weeks at a time. But with Sabrewing technology, any of those four sections can be inspected individually, meaning the aircraft can stay in operation with a replacement section that can be replaced in less than 24 hours.

Whether or not the world is ready for drone delivery remains a topic of discussion, but when it comes to adopting aircraft that can carry cargo longer and further, many companies are more than ready. Such applications might end up defining and redefining much more for those companies and the entire drone industry.

Comments