The Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) last month approved the Rs 4,077-crore Deep Ocean Mission proposed by the Ministry of Earth Sciences. More than Rs 2,800 crore will be spent during the first phase of the five-year mission.

What is Deep Ocean Mission?

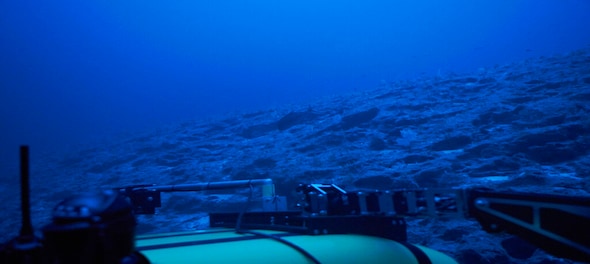

Deep sea is the part of the ocean which is 200 m below its surface, where light begins to dwindle. It comprises 90 percent of the ocean and 50 percent of the Earth’s surface. Only 0.0001 percent of the deep seafloor has been explored, according to an article published in The Guardian.

India wants to develop technologies for the exploration of the ocean floor, which is the main objective of the Mission. It wants to explore the ridges at depths of up to 6,000 metres, which would be a precursor to deep-sea mining, when it is permitted under international agreements.

A three-member crewed submersible vehicle, autonomous prospecting vehicles, and an integrated mining system would be developed. Such strategic technologies are currently at various stages of highly-protected development and deployment mostly by developed countries like the US, China, Russia, France, Germany, Japan and South Korea. All eyes are on a completely new and vast resource base for industrial raw materials.

India’s other objectives are to study the deep-sea flora and fauna and potential utilisation of bio-resources. Besides, the Mission involves production of renewable energy through ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) technology and linked desalination plants for freshwater. It also includes a proposed advanced marine station for ocean biology and engineering and on-site business incubators.

These are part of the Centre’s ‘Blue Economy Initiative,’ identified in the Vision of New India by 2030 that was enunciated in 2019, according to a report published in The Leaflet.

International Laws on Deep-Sea Mining

Humans have known for around 150 years that minerals exist on the ocean floor, but it was only in the 1970-80s that we developed the technology to exploit those resources.

In 1872-76, British warship HMS Challenger first dredged up some black matter made almost entirely of pure manganese oxide from over the eight km deep Mariana Trench in the western Pacific Ocean. Mariana Trench is considered to be the deepest point on Earth.

As technologies to study them developed, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly between 1967 and 1982 pursued efforts to regulate these resources, designated as "common heritage of mankind." In 1970, it adopted the Declaration of Principles Governing the Sea-Bed and the Ocean Floor and the Subsoil Thereof Beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction.

In 1982, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted by 167 member states and the European Union.

Under the law, an International Seabed Authority (ISA) was mandated with its headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica, "to organise, regulate and control all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area for the benefit of mankind as a whole."

Since then, the ISA has issued 30 contracts for mineral exploration on an area of over 1.4 million sq km, mostly in the Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean, according to The Guardian.

According to the article, the companies involved in exploration are eyeing potato-like polymetallic nodules -- ores rich in manganese, nickel, cobalt and rare earth metals -- that dot the deep-sea surface. The nodules, around 10 cm in diameter, reportedly form at the staggeringly slow rate of just a few centimetres every million years.

The Metals Company, one of the big companies in the nascent industry, describes them as "a battery in a rock." Polymetallic nodules contain rich concentrations of the base metals needed to make batteries.

So far, licences have only been issued for exploration and not mining. The ISA, however, is working on a regulatory framework for mining.

It was due to release and adopt a code for the exploitation of deep seas in July 2020, but was delayed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The ISA aims to resume meetings this year.

Environmental Impact?

According to The Guardian, The Metals Company (earlier DeepGreen) considers deep-sea mining less environmentally and socially damaging than terrestrial mining. It says deep-sea mining is crucial for transition to a greener economy as the nodules contain the minerals needed for manufacturing batteries used in electric vehicles.

Its proposal is to suck up the nodules through long pipes in the CCZ. It would then process the nodules on board ships and pump back the extra sediment into the sea.

The Metal Company also says it expects to submit its environmental impact statement in 2023, hoping to begin commercial mining in 2024.

Environmentalists, however, have raised concerns about the impact of the deep-sea mining on the marine ecosystem, particularly considering the fact that there is still a lot to know about it. Also, the reproduction and growth of marine life at those depths is very slow.

An experiment involving the extraction of nodules from the CCZ in 1978 points to the long-lasting damage. When the area was revisited in 2004, researchers could still find clear markings of the tracks left by mining vehicles 26 years ago. There was also a reduced diversity of organisms in the disturbed area.

Meanwhile, Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an anti-deep-sea mining group, has been calling for a moratorium on such mining.

Environmental concerns range from noise pollution interfering with deep-sea species’ ability to communicate and detect food, rise in temperature from mining operation, waste accumulation and heavy vehicles crushing seabed organisms.

Several Pacific nations like Vanuatu, Fiji and Papua New Guinea have called for a regional moratorium on deep-sea mining to learn more about potential environmental harms.

This month, the EU parliament echoed the Pacific nations on promoting a moratorium until the environmental impact of deep seabed mining could be better managed.

What is Deep Ocean Mission?

Deep sea is the part of the ocean which is 200 m below its surface, where light begins to dwindle. It comprises 90 percent of the ocean and 50 percent of the Earth’s surface. Only 0.0001 percent of the deep seafloor has been explored, according to an article published in The Guardian.

India wants to develop technologies for the exploration of the ocean floor, which is the main objective of the Mission. It wants to explore the ridges at depths of up to 6,000 metres, which would be a precursor to deep-sea mining, when it is permitted under international agreements.

A three-member crewed submersible vehicle, autonomous prospecting vehicles, and an integrated mining system would be developed. Such strategic technologies are currently at various stages of highly-protected development and deployment mostly by developed countries like the US, China, Russia, France, Germany, Japan and South Korea. All eyes are on a completely new and vast resource base for industrial raw materials.

India’s other objectives are to study the deep-sea flora and fauna and potential utilisation of bio-resources. Besides, the Mission involves production of renewable energy through ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) technology and linked desalination plants for freshwater. It also includes a proposed advanced marine station for ocean biology and engineering and on-site business incubators.

These are part of the Centre’s ‘Blue Economy Initiative,’ identified in the Vision of New India by 2030 that was enunciated in 2019, according to a report published in The Leaflet.

International Laws on Deep-Sea Mining

Humans have known for around 150 years that minerals exist on the ocean floor, but it was only in the 1970-80s that we developed the technology to exploit those resources.

In 1872-76, British warship HMS Challenger first dredged up some black matter made almost entirely of pure manganese oxide from over the eight km deep Mariana Trench in the western Pacific Ocean. Mariana Trench is considered to be the deepest point on Earth.

As technologies to study them developed, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly between 1967 and 1982 pursued efforts to regulate these resources, designated as "common heritage of mankind." In 1970, it adopted the Declaration of Principles Governing the Sea-Bed and the Ocean Floor and the Subsoil Thereof Beyond the Limits of National Jurisdiction.

In 1982, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted by 167 member states and the European Union.

Under the law, an International Seabed Authority (ISA) was mandated with its headquarters in Kingston, Jamaica, "to organise, regulate and control all mineral-related activities in the international seabed area for the benefit of mankind as a whole."

Since then, the ISA has issued 30 contracts for mineral exploration on an area of over 1.4 million sq km, mostly in the Clarion-Clipperton fracture zone (CCZ) in the Pacific Ocean, according to The Guardian.

According to the article, the companies involved in exploration are eyeing potato-like polymetallic nodules -- ores rich in manganese, nickel, cobalt and rare earth metals -- that dot the deep-sea surface. The nodules, around 10 cm in diameter, reportedly form at the staggeringly slow rate of just a few centimetres every million years.

The Metals Company, one of the big companies in the nascent industry, describes them as "a battery in a rock." Polymetallic nodules contain rich concentrations of the base metals needed to make batteries.

So far, licences have only been issued for exploration and not mining. The ISA, however, is working on a regulatory framework for mining.

It was due to release and adopt a code for the exploitation of deep seas in July 2020, but was delayed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The ISA aims to resume meetings this year.

Environmental Impact?

According to The Guardian, The Metals Company (earlier DeepGreen) considers deep-sea mining less environmentally and socially damaging than terrestrial mining. It says deep-sea mining is crucial for transition to a greener economy as the nodules contain the minerals needed for manufacturing batteries used in electric vehicles.

Its proposal is to suck up the nodules through long pipes in the CCZ. It would then process the nodules on board ships and pump back the extra sediment into the sea.

The Metal Company also says it expects to submit its environmental impact statement in 2023, hoping to begin commercial mining in 2024.

Environmentalists, however, have raised concerns about the impact of the deep-sea mining on the marine ecosystem, particularly considering the fact that there is still a lot to know about it. Also, the reproduction and growth of marine life at those depths is very slow.

An experiment involving the extraction of nodules from the CCZ in 1978 points to the long-lasting damage. When the area was revisited in 2004, researchers could still find clear markings of the tracks left by mining vehicles 26 years ago. There was also a reduced diversity of organisms in the disturbed area.

Meanwhile, Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an anti-deep-sea mining group, has been calling for a moratorium on such mining.

Environmental concerns range from noise pollution interfering with deep-sea species’ ability to communicate and detect food, rise in temperature from mining operation, waste accumulation and heavy vehicles crushing seabed organisms.

Several Pacific nations like Vanuatu, Fiji and Papua New Guinea have called for a regional moratorium on deep-sea mining to learn more about potential environmental harms.

This month, the EU parliament echoed the Pacific nations on promoting a moratorium until the environmental impact of deep seabed mining could be better managed.

Check out our in-depth Market Coverage, Business News & get real-time Stock Market Updates on CNBC-TV18. Also, Watch our channels CNBC-TV18, CNBC Awaaz and CNBC Bajar Live on-the-go!