In 2012, Chinese supremo, Xi Jinping, on taking over the party leadership, visited the Museum of Revolution, where he declared, “Glorious 5,000 years of the history of Chinese nation, 95 years of historical struggle of the CCP and 38 years development miracle of reform and opening up have already declared to the world with indisputable facts that we are qualified to be the leader.” He pledged to turn China into an ‘invincible force with wisdom and power.’ If China succeeds in its present face-off with India, it would have achieved Xi Jinping’s first milestone; force India to acknowledge the limits of its power and agree to play second fiddle to China. India, therefore, will have to dig deep into its civilisational past to defeat Chinese hegemonistic ambitions. The outcome of the present face-off is, therefore, crucial.

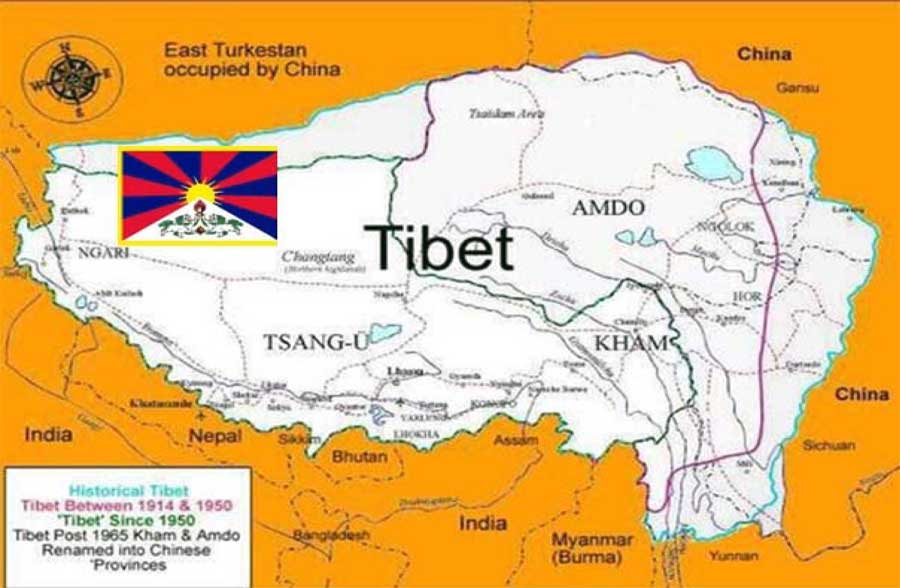

For decades after the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of China invaded Tibet on October 07, 1950, and later in the 1950s, bit off Aksai Chin from Ladakh in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, the loss of such strategic territory has remained as remote from people’s minds as the area itself. Today, Tibet, Aksai Chin and many of those remote areas are back in focus because of the violent face-off between Indian soldiers and PLA troops in the Galwan area of Aksai Chin. This is the first violent clash between the two armies in decades and lays bare Chinese intentions. It appears that Deng Xiaoping’s advice to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to ‘bide your time and hide your strength’ has served its purpose and China now feels strong enough to project its strength at a time when it gave the world COVID-19 and kept it busy with managing its horrendous fallout.

Abandoning Tibet

Tibet is called the ‘Roof of the World’ and for India, just across the Himalayas, it has, for centuries, been much more than just our roof. Tibet got Buddhism from India (much of it through Kumarajiva of Kashmir in the seventh century AD), its trade with South Asia was through India and the free flow of pilgrims and traders between India and Tibet had established unbroken and century-old links between Tibet and India. For China, Tibet was too remote and too far. Prior to the conquest of North India by Muslim invaders/rulers, Tibet was more closely connected to India than China but much changed after the Communist revolution of 1949 in China.

For centuries, Tibet remained an independent entity, even though China has exercised it suzerainty over it for brief periods, which the Tibetans always resented. In 821 CE, Tibet and China entered into a peace treaty. Tibet was represented by its great Emperor, Tritsuk Detsun and China, by its Chinese counterpart. The Treaty inter-alia, declared, “Seeking in their far-reaching wisdom to prevent all causes of harm to the welfare of their countries now or in future.” Subsequently, this Peace Treaty was carved in Tibetan and Chinese language on a stone pillar which was placed in front of Jhokhang Cathedral in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa. The Treaty further stated, “Tibet and China shall abide by the frontiers of which they are now in occupation. All to the East of the country of great China and all to the West, without question, the great country of Tibet. Henceforth, from neither side shall there be any waging of war nor seizing of territory. If any person incurs suspicion, he shall be arrested. Tibetans shall be happy in the land of Tibet and Chinese shall be happy in the land of China. Even the frontier guards will have no fear or anxiety.”

No treaty signed between two countries could be more specific than this, as far as assertion of their identity as two independent sovereign nations was concerned. In the 12th and 16th century, Tibetan Lamas were quite strong and even ruled certain parts of China. Yet, today, Tibet is an inalienable part of China and the border guards have shifted to the border with India.

The success of the Chinese revolution in 1911 (not the Communist revolution of 1949), saw the end of the Qing Dynasty, the last Chinese dynasty. Consequently, Tibet, Mongolia and China became three separate countries. In February 1912, after China became a republic, Tibet declared its independence and the Chinese soldiers were asked to leave the country.

During the British rule of India, Britain treated Tibet as an autonomous buffer state between India and China. Britain had recognised China’s suzerainty, but not its sovereignty over Tibet. Britain protected Tibet’s autonomy by recognising its treaty-making powers, especially in its relations with India. This was the reason why a Tibetan delegation was invited to the Asian Relations Conference in Delhi in 1946 by Jawahar Lal Nehru. In September that year, the Indian Government was assured that all previous treaty commitments and conventions between Tibet and Britain would be respected. But all this changed soon.

On October 07, 1950, China invaded Eastern Tibet and brutally smashed the ill-prepared Tibetan Army. The PLA struck terror into the hearts of Tibetans when the offensive began and succeeded in pulverising the resistance till victory was gained. This compelled the Dalai Lama to appeal to the UK, the USA, India and Nepal seeking assistance against the invaders. While the US and Nepal remained silent, Britain said it had no interest in the area after it had left India. But India went out of its way to announce that it accepted Chinese claim of sovereignty over Tibet and in fact, advised the Dalai Lama to also follow suit. China, thereafter, continued to push westwards. In April 1951, the PLA forged the seals of the Lhasa government which they used to force a 17-point Agreement on the Tibetan delegation and by September 1951, the PLA entered Lhasa.

At that time, if India had even a little understanding of its geo-strategic interests/requirements, it could have rendered military assistance to Dalai Lama. It must be noted that China became strong only after the Korean War (1950 – 1953). Prior to that, it had only a large-sized but rag-tag PLA. The other important and crucial factor was that the Tibetan plateau was far more accessible from India than from China. Had India said ‘NO’ to Chinese invasion of Tibet, things would have been different. On the other hand, India seemed to be too anxious to legitimise Chinese occupation of an autonomous buffer between India and China, and was keen to help China to demarcate its borders with India.

It is important to know the reaction of the Indian leadership to the developing situation in Tibet which would have far reaching consequences for our nation. Between 1950 and 1952, Sunil Sinha was the official in charge of the Indian Mission in Lhasa and a witness to the machinations of the Chinese in Tibet. Reporting the matter truthfully to New Delhi, he wrote, “Initially, the Red Army Generals were all sweet and honey towards the Tibetans. The Chinese Generals handled the Tibetans delicately and with patience, trying to get them gradually into their fold, trying to win their hearts and minds. It was subtle and hardly visible, and the largesse that poured in was phenomenal…” Sinha then also referred to the brutal offensive of the PLA against the Tibetans to gain victory.

Nehru found the young Mandarin-speaking diplomat’s language rather irritating. According to Nehru, “…Sinha could not grasp that Chinese had come to help the Tibetans rid them of their medieval mindset… and in any case, the destiny of India and China was bound together for the good of humanity.” In the meanwhile, India’s Tibet policy under its ambassador in Peking (later Beijing), K.M Panniker had radically changed after he was suddenly promoted as Nehru’s Chief Advisor for Tibet affairs. Nehru’s directions to him were clear, “Conflict with China had to be avoided at any cost”. To Nehru, world peace mattered more than the country’s interests and to achieve that objective, “…Tibet could be sacrificed”. Sinha continued to report the deteriorating ground situation in Tibet. Nehru was not too happy with these reports. On November 07, 1950, he wrote to Sinha, “The Government of India has noticed that certain communications from Lhasa regarding Tibet are dogmatic, disputatious and admonitory. We, of course, want our representative to give us full information… But once the decision has been taken by the Government (Read – to abandon Tibet to its fate), it should be accepted gracefully and followed faithfully; any insinuation that the Government has been acting wrongly or improperly is objectionable.” Obviously, Nehru did not like Sinha being too sympathetic to Tibet when it was getting crushed under the PLA boots. Around the same time, (November 07, 1950) Nehru had received a letter from his Deputy PM, the dying Sardar Patel, warning of the dangers of Nehru’s policy of ‘friendship with China at any cost.’

Sinha felt hurt at Nehru’s admonition and wrote back to his boss in the MEA, “My shortcoming is inexperience. I know, however, that I have striven to carry out the Government of India’s (GOI) policies in letter and spirit. In my telegram, I had tried to reflect faithfully the reaction of the Tibetan government to the situation facing them in the belief that GOI would like to know.” Just before the end of his tenure in Lhasa in the summer of 1952, Sinha requested the GOI for a loan of Rs 200,000 to help the forces fighting for Tibet’s independence. Nehru was furious and wrote back, “It would be improper and unwise for our representative to get involved in Tibetan domestic affairs or intrigues… we have to judge these matters from a larger world point of view which probably our Tibetan friends have no means of appreciating.”

After his move back to New Delhi, Sinha was made an Officer on Special Duty (OSD) in the MEA. In that capacity, he wrote a memo prophetically titled ‘Chinese designs in the North East Frontier of India.’ Nehru felt annoyed and wrote back, “I find Mr Sinha’s approach to be coloured very much by certain ideas and conceptions which prevent him from taking an objective view of the situation. Sinha looks back with certain nostalgia to the past when the British exercised a good deal of control over Tibet and he would have liked very much for India to take the place of Britain of those days.” Gradually, the Chinese continued to strengthen their hold on all aspects of Tibetan life and their unique institutions. The only Chinese now visible in Western Tibet were the communist troops who came there in 1951 from Khotan.

In the summer of 1951, K.M. Pannikar visited India and Nehru stated during a press conference on November 03, 1951, “For the first time, China possesses a strong central government whose decrees run even to Sinkiang and Tibet. Our own relations with China are definitively friendly.” During the same press conference, he was asked to comment on the Chinese incursions in Tibet as the first surveys for Lhasa- Sinkiang were carried out around this time and the Chinese presence was reported to India through many sources, including by L.S. Jangapani, India’s Trade Agent at Gartok.

In June 1952, Nehru now said, “…China is now exercising suzerainty over Tibet… now that Tibet was no longer an independent country, a decision had been taken to demote India’s diplomatic relations with Tibet.” As the situation developed adversely for India, Nehru kept beating around the bush. I have mentioned above the age-old ties that India had enjoyed with Tibet. In Kashgar (Xinjiang) India had a centuries-old consulate which served as a hub of trade between Central Asia and the sub-continent. In 1953, China unilaterally closed the consulate (as also the trade). This should have been viewed as an ominous sign by Nehru, but he did not even as much as protest and seemed to justify the Chinese unilateral action by stating in the Parliament, in December 1953, “Some major changes have taken place there (Kashgar)…but when these revolutionary changes took place there, we had to close our consulate. I It is perfectly true that the Chinese Government told us that they intended to treat Sinkiang (Xinjiang) as a closed area.” Nehru totally overlooked the fact that for centuries, India had traded with Central Asia and more particularly with Kashgar, Yarkand and Khotan and now needed to sacrifice all that to make the Chinese revolution a success! Even when China did this, a large volume of trade was taking place between Kashmir and Central Asia across the Karakoram Pass.

Loss of Aksai Chin

China has under its occupation 38,256 sq km in Aksai Chin. Though the region is barren and nearly devoid of habitation, it has great strategic significance for China, as its road connecting Lhasa in Tibet with Kashgar in Xinjiang passes through this region. China started construction of this road (later named, NH 219) in the summer of 1955, and completed it in October 1957. It was formally inaugurated on October 06, 1957, with a ceremony in Gartok. The Chinese newspaper Kuanming Jihpao reported, “The Xinjiang-Tibet Highway is 1,179 km long, of which 915 km run in an area which is 4,000 metres above sea level, 130 km above 5,000 metres, with the highest point being at 5,500 metres.” It was to conceal the construction of this road that China had closed down this consulate.

According to several thousand US declassified documents, circa 2016-2017, the CIA had known as early as 1954, about the construction of a road connecting Lhasa in Tibet with Kashgar in Xinjiang. It had also learnt that, as late as 1952, the 2 Cavalry Regiment of PLA, commanded by Col Han Tse Minh, had set up its headquarters at Gartok, the main trade centre in West Tibet. Its troops, along with camels and horses, had been deployed at Rudok, near Pangong Tso and Koyul in the Indus valley. Han Tse Minh had asserted, “When these roads are completed, the Chinese Communists would close the Tibet-Ladakh border to trade.” All this had been done by China in the most secretive manner. It was to ensure the secrecy about the construction of this road that our Consulate at Kashgar had been closed down.

The stand that GOI had taken then was that it did not know about this road. As mentioned above, this is not borne out by various articles and books written by those who dealt with the subject and the lately declassified documents of CIA as stated above. Besides, far too many incidents had taken place in early fifties which should have woken up the GOI from its delusional ‘Hindi-Cheeni Bhai Bhai’ syndrome.

Around the same time, the Indian Military Attaché in Peking, Brigadier SS Malikhad, in his report to the GOI, made references to this road construction activity. A year later, he confirmed this by adding that the road passed through the Indian territory of Aksai Chin. One of the most interesting confirmations came through the British adventurer, Sydney Wignall, who died on April 4, 2020, in the UK at the age of 89.

In 1955, he had led the first Welsh Himalayan Expedition to climb Mount Gurla Mandhata, close to Mount Kailash (height 25,355ft), overlooking the Mansarovar and Rakshastal lakes in Tibet, North of the Himalayan watershed. Prior to the commencement of the expedition, Indian Military Intelligence officers in London had contacted him and asked him to collect information on this road. During the expedition, Wignall collected vital information about the feverish construction activity on this road. He was, however, imprisoned by the PLA on the suspicion of being a CIA spy. The Chinese eventually released him after some weeks on a high altitude pass, hoping that lack of oxygen, intense cold and snow blizzards would kill him. However, the redoubtable adventurer somehow made it back to India and reported the matter to his ‘contact’ in the Military Intelligence Directorate.

Through General K.S. Thimmaya, the soon-to-be-made the Chief of the Army Staff, the matter reached the highest levels of the Government, but it was treated with disdain. In his book, Spy on the Roof of the World, Wignall writes that he was later told by his ‘contact’ in Military Intelligence, “Our illustrious Prime Minister Nehru, who is so busy on the world stage telling the rest of the mankind how to live, has too little time to attend to the security of his own country. Your material was shown to Nehru by one of our senior officers, who plugged hard. He was criticised by Krishna Menon in Nehru’s presence for lapping up ‘American CIA agent-provocateur propaganda.’ Menon has completely suppressed your information.” “So, it was all for nothing?” Wignall had asked. “Perhaps not, we will keep working away at Nehru. Some day he must see the light and realise the threat that the Communist Chinese occupation of Tibet poses to India,” replied the contact. No wonder, General Thimmaya on the eve of his retirement in 1961, said while speaking to his officers, “I hope that I am not leaving you as cannon fodder for the Chinese communists.”

Once the Aksai Chin road became operational, the trade between Tibet and India that had thrived for centuries, stopped completely. India’s trade access with Central Asia too was permanently severed. After the Chinese aggression of 1962, the Official Report published by the Ministry of Defence, the GOI, stated, “China started constructing motorable road in summer 1955… on October 6, 1957, the Sinkiang-Tibet road was formally opened with a ceremony in Gartok and 12 trucks on a trial run from Yarkand reached Gartok.” Though the existence of this road was discussed in Lok Sabha in August 1959, it was in 1955, that the Government had information about this road, as mentioned earlier.

The Chinese now started playing tricks. Kushok Bakula Rimpoche, the youngest child of Nangwa Thayas, the King of Matho and Princess Yeshes Wangmo of the royal house of Zangla, had been recognised by the 13th Dalai Lama as the reincarnation of Bakula Arhat, one of the legendary 16 Arhats who were direct disciples of Gautama Buddha. Kushak Bakula had a long and distinguished career, including being part of the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly. In late 1955, Bakula was permitted by the Chinese to visit Tibet, but insisted that he did not need to carry an Indian passport since pilgrims were permitted to travel without one. India saw through the trick that the Chinese did not intend giving a diplomatic passport to Bakula, as he was at that time, a Minister in the Jammu and Kashmir Government. However, after protracted negotiations, spearheaded by T.N. Kaul, the Chinese agreed to issue the passport. Bakula was accompanied by Durga Das Khosla, an official of the Jammu and Kashmir Political department.

After a three-month stay at Lhasa, Bakula returned and met Nehru and briefed him on the situation in Tibet. In his written report, he ended his description of what he saw there, thus, “…Yet the deep seated suspicion of Tibetans – both Lamas and laymen – against the bonafide of the Chinese people is all common and contiguous.” Similarly, on his return, Khosla’s report to the Government contained a following paragraph, “The Chinese government has secretly circulated a new map of Tibet in which they have shown the whole of Aksai Chin as part of Tibet. Kashmir’s Northern border as illustrated in the map shows some daring incursions into our Karakoram area of Northern Ladakh and Baltistan.” But Delhi paid no heed.

McMahon Line and China’s About Turn

In 1913, Captain Frederick Baily and Captain Morshead suryeyed the Himalayas to help Henry McMahon, British India’s Foreign Secretary to draw up a map for the ensuing Simla (now Shimla) Conference next year. In this conference, Henry McMahon, Lochan Shatra, the Tibetan Plenipotentiary and Ivan Chen, the Chinese representative, sat on the same footing. On the first day of the conference, the Plenipotentiaries had verified their credentials and found them bonafide and accepted by all. The Simla convention ceded Tawang (present day Arunachal Pradesh) and other Tibetan areas to Britain. The convention in Simla was signed by India and Tibet and initialed by China. Though the agreement on border between China and Tibet could not be resolved, the border between Tibet and India, was drawn with the help of a thick red line on a double-page map, which came to be known as the McMahon Line. It was under this agreement that India had established a military presence in both Lhasa and Gyantse; actually, India had more than a consulate at Lhasa – it had a full-fledged mission till the end of 1952.

India had inherited many rights and privileges in Tibet from the 1914 Simla Tripartite Conference. Apart from the mission in Lhasa, India had three trade marts and its agents were posted at Gyantse, Gartok (Western Tibet) and Yatung (in Chhumbi valley near Sikkim border). These agents were entitled to military escorts. The Post and Telegraph Service, a chain of rest houses and principality of Minsar (near Mount Kailash) were also under the GOI’s control. Panchsheel Agreement signed between India and China in April 1954, confirmed the presence of the Consulate General and Trade Mart. Later, In September 1958, Nehru paid a visit to the Trade Agency at Yatung, primarily because of the beautiful imposing building that hosted the Trade Agency. It was destroyed by the PLA after the 1962 war.

By 1955, all these missions were handed over to the Chinese without any compensation or without even trying to get a fair settlement of the border issue. India simply gave up the rights under the Simla Treaty of 1914 and withdrew its garrison from Lhasa and Gyantse. China’s smart Foreign Minister cum Prime Minister Zhou Enlai took advantage of Nehru’s willingness to let go of Tibet. He told the China-loving Indian Ambassador, Pannikar, shortly thereafter, “…Presumed that India had no intention of claiming special rights arising from the unequal treaties of the past and was prepared to negotiate a new and permanent relationship safeguarding legitimate interests.” Not only did China not offer anything in return to India for this generosity, India went a step ahead by allowing China to open a consulate in Mumbai. Unbelievable! Hugh Edward Richardson, the last Head of the British Mission in Lhasa, remarked, “…Tibet had ceased to be independent and it left unresolved the fate of the special rights acquired when Tibet had been in a position to make its own treaties with foreign powers.”

After the Dalai Lama sought refuge in India in 1959, the staff of the Consulate and Trade Mart kept facing increasing harassment at the hands of the Chinese. After the Panchsheel Agreement lapsed in April 1962, the Trade Marts were closed and the Chinese asked the Indian Government to vacate the premises. On December 03, 1962, the MEA sent a note to China, “The GOI has decided to discontinue the Indian Consulates-General at Lhasa and Shanghai from December 15, 1962, and to withdraw their personnel manning these.” That brought down the curtains on our relations with the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR).

On October 08, 1959, Lt Gen SPP Thorat, GOC-in-C Eastern Command, sent a note to the Chief of the Army Staff at Delhi, detailing the threat posed by China on India’s Eastern borders. General Thorat gave a day to day account of how the defences would fall in the likelihood of a Chinese offensive in the NEFA. The report was forwarded by the Chief to the Defence Minister, Krishna Menon. The brash and arrogant Menon ‘rejected the report outright’ and what is worse, called General Thorat an ‘alarmist’.

Overview

China had never raised the issue of any boundary dispute between Tibet and India till it physically occupied Tibet in 1950. Due to the nature of the relationship between the two countries since ancient times, the border between Tibet and India had always remained undefined and hence unenforced. Traditionally Indian pilgrims going to Kailash – Mansarovar were not considered as those going to a foreign country. But Chinese occupation of Tibet in 1950 changed all that. Chinese now demanded to see the passports of the Indian pilgrims. Thereafter, China started laying claim to the areas across Ladakh, Kedarnath, Badrinath, Sikkim and NEFA (now Arunachal Pradesh).

Arunachal Pradesh’s relationship with Tibet was based on the recognition of the temporal and spiritual authority of the Dalai Lama by the people of the state. In 1959, when the Dalai Lama was forced to seek refuge in India, the event cut off the only connection between the two. The crux of the matter is that the recognition by India of Chinese claim over Tibet in 1950 opened a Pandora’s box. Once China’s claim over Tibet was accepted, it became difficult to rule out the corresponding territorial claims by China to these areas.

Chinese Grand Strategy

China’s grand strategy has twin objectives – to extend its territory North of the Galwan river- where the PLA has currently camped – up to the Karakoram Pass and then onto the Shaksgam valley which Pakistan gifted to it in 1963. China is also looking to occupy the Northern parts of Aksai Chin to increase the depth to their important Highway 219 to protect their Achilles heel – Tibet and Xinjiang. China’s aggressive posturing is also driven by its desire to own the Indus water system. This will allow them to control water resources in the Ladakh region as the River Indus originates in Tibet and goes via Northern areas to Pakistan. China’s requirement of enormous quantities of water is driven by its desire to cut down on its huge import bill of microchips, which stood at a whopping $230 billion in 2018. Its eyes are also firmly fixed on multiple glaciers in Shaksgam, Raksham, Shimshal and Aghil valleys. It should, therefore, come as no surprise that China is now involved in a dam building frenzy in Gilgit-Baltistan. The two mega dams costing a whopping $27 billion, with a capacity of 7100 MW (Bunji Dam) and 4500 MW (Bhasha dam), should put this in perspective. Incidentally, India does not have a single dam measuring even one-third the size of the Bunji dam.

In 2012, Chinese supremo, Xi Jinping, on taking over the party leadership visited the Museum of Revolution, where he declared, “Glorious 5,000 years of the history of Chinese nation, 95 years of historical struggle of the CCP and 38 years development miracle of reform and opening up have already declared to the world with indisputable facts that we are qualified to be the leader.” He pledged to turn China into an ‘invincible force with wisdom and power.’ If China succeeds in its present face-off with India, it would have achieved Xi Jinping’s first milestone; force India to acknowledge the limits of its power and agree to play second fiddle to China. India, therefore, will have to dig deep into its civilisational past to defeat Chinese hegemonistic ambitions. The outcome of the present face-off is, therefore, crucial.

The current Chinese confrontation is part of their larger plans, which are briefly mentioned in the second last para and they are consistently following their agenda since 1950s onwards. They are fully focused to achieve their aim, preparing for it, using all sorts of tactics. Our political leadership did make a blunder by not waking up to the sit and reacting / responding appropriately. Year by year we are loosing our territory without any successful response to regain what we already lost. First of all we must derecognise ( or make null and wide) the 2003 Vajpayee- Wen declaration, second must raise Tibet issue at all international platforms and openly support Tibet independence as Pakistan supports Kashmir. Then we need to have a National Security policy for short and long term periods and change our strategy from defensive to offensive and proactive. Apart from suitable budget, Consistency in following the policy (irrespective of any political outfit in power) is a must.

Fascinating article.

Unfortunately, we don’t seem to learn from history – and may end up making a similar mistake by abandoning Afghanistan to the Taliban.