The oceans are just too big to police—and if you want just one example, consider fishing.

Illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing nets up to 26 million tons of fish each year, which adds up to almost a quarter of the profits of legal fishing. Powered by a shadow fleet, this multi-billion-dollar criminal enterprise hurts legit fishermen and wreaks environmental havoc through overfishing.

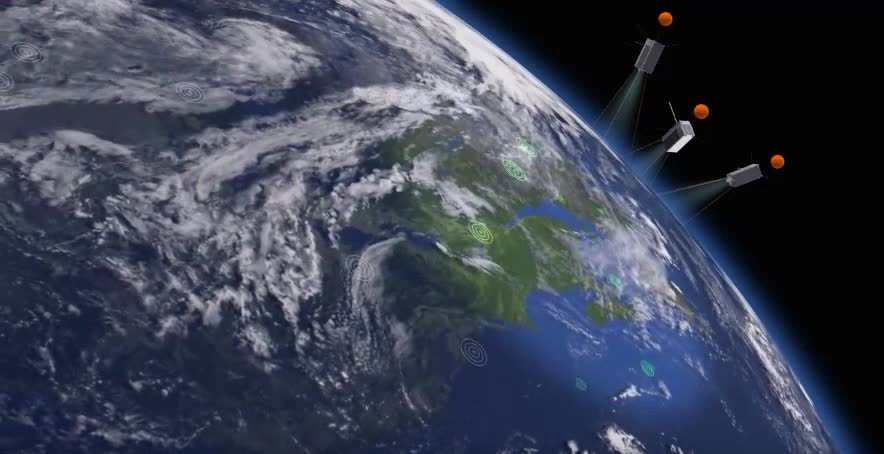

The vastness of earth's open waters allow such a black market to thrive. But in a world increasingly surveilled by satellites in low-Earth orbit, technology is making a once impossible mission a little less impossible.

In the Beginning

On December 3, 2018, at Vandenberg Air Force Base, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket broke records by placing 64 small satellites into orbit with just one mission. And among this new space flotilla were small satellites representing the vanguard for a new generation of global surveillance.

Hungry for more data, Global Fishing Watch, a collaboration among conservation group Oceana, technology giant Google, and environmental nonprofit SkyTruth, is eager to use those new satellites to see “all the ships, all the time," creating an indispensable tool for catching illegal activity on the high seas.

“It is now within the foreseeable future that you can expect to be able to track every vessel on the surface of the earth,” says Tony Long, Global Fishing Watch’s CEO.

In 2016 Global Fishing Watch started with data from the radio beacons all ships carry to avoid collisions, mapping their movements to spot fishing in illegal areas. However, ship captains can counter such surveillance by simply turning the beacons off—a potentially dangerous measure that removes them from the map.

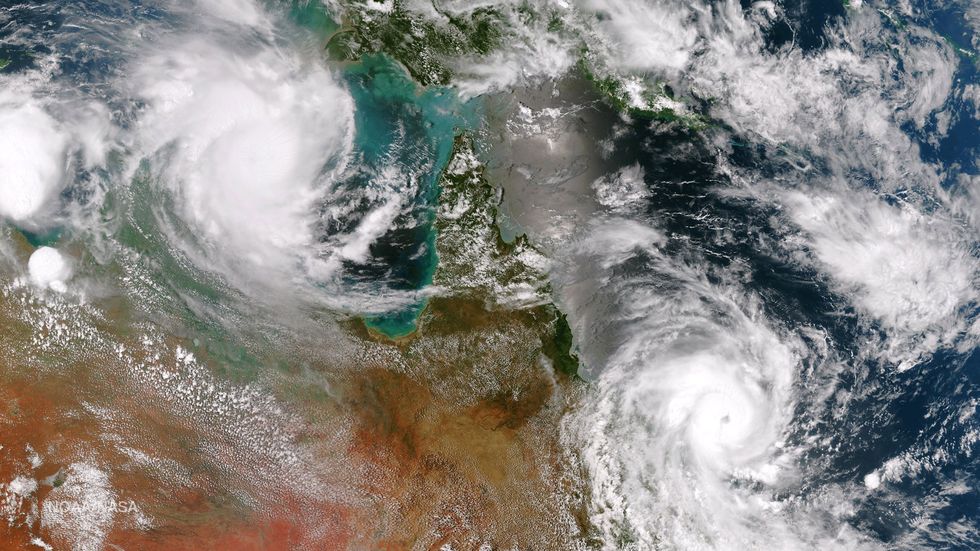

In order to circumvent this shady behavior, Global Fishing Watch started supplementing beacon locations with data from earth-observation satellites. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) maps cloud cover. But with some smart processing, Global Fisher Watch used their data to locate small, bright patches at night, such as floodlights used for squid fishing.

But satellite imagery is only useful on clear days, and while the NOAA imagery is free, the price for commercial data far exceeded Global Fishery Watch’s budget.

They needed new tools if they ever hoped to keep a watchful eye on the world's oceans.

All-Seeing Radar Eyes

The European Space Agency launched Sentinel-1A, the first of four satellites, on a mission to map sea-ice cover, assist forest management, and tackle other large-scale tasks. But by using new algorithms, Global Fishing Watch could pick up reflections from the metal hulls of individual ships in the earth's oceans.

“Radar is good,” says Paul Woods, chief technology officer at Global Fishing Watch. “It goes through the clouds, it works at night, and it sees all the vessels, whether broadcasting or not.”

But radar satellites are rare and expensive. Sentinel-1, launched in 2014, is the size of an SUV and weighs two tons, and radar imagery demand far outpaces supply.

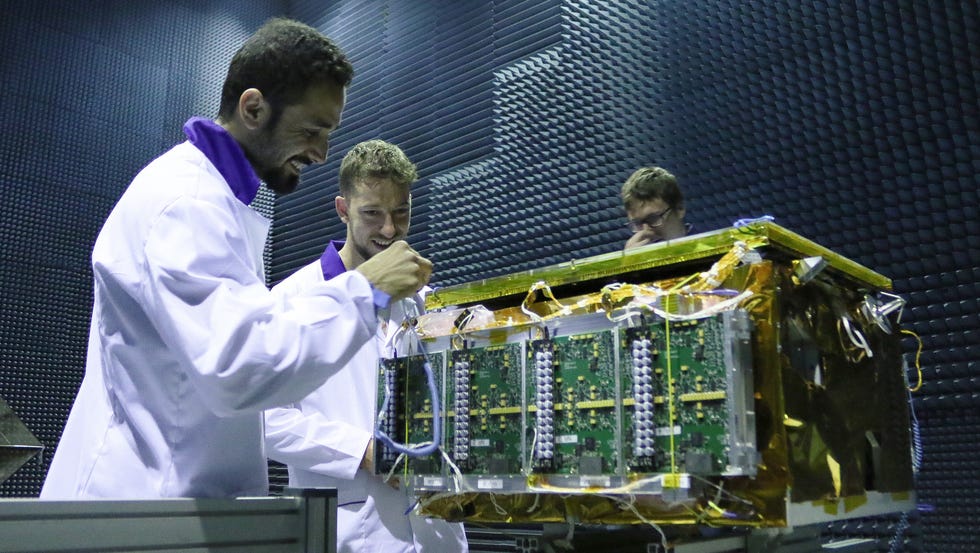

“What was missing was a radar sensor that could go in a small satellite,” says Pekka Laurila, co-founder of Finnish startup ICEYE. “And that was the technology we developed.”

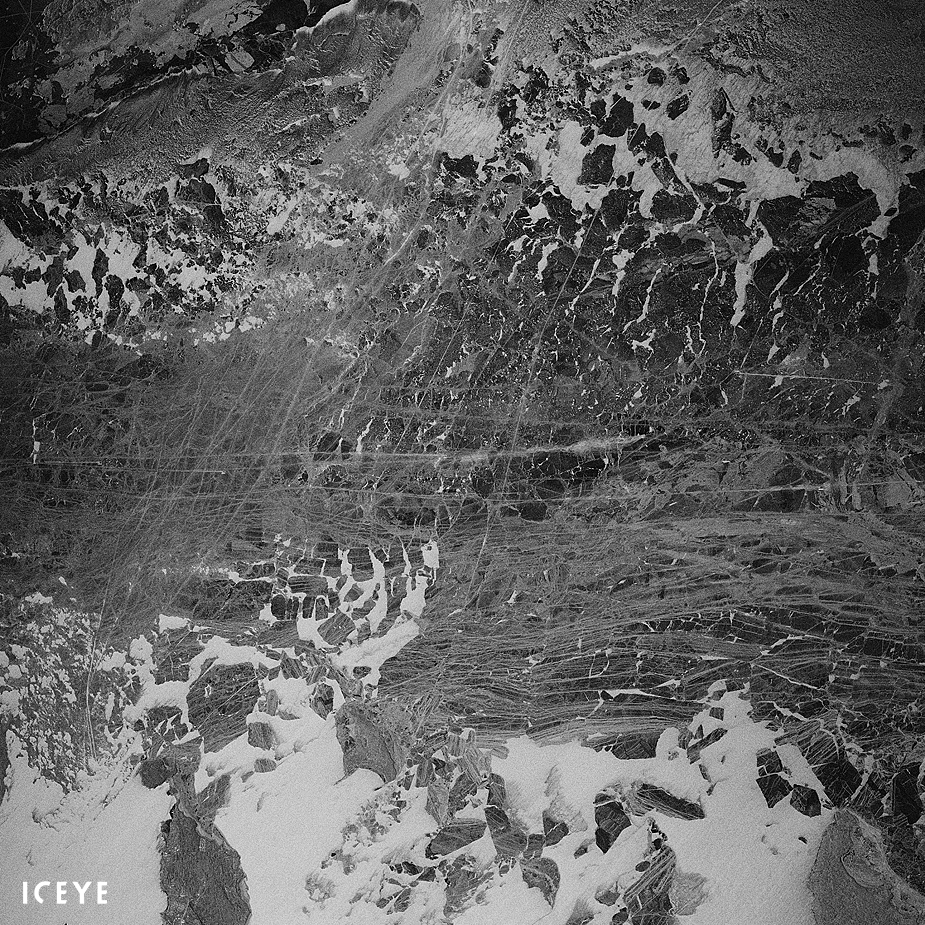

ICEYE's original aim, much like that of Sentinel-1, was observing ice cover and monitoring dangerous icebergs but similarly its radar could be tweaked for spotting ships as well. In early 2018, the company launched its prototype ICEYE-X1 to prove the technology and ICEYE-X2, their first commercial satellite, was put into orbit in early December.

Weighing much less than Sentinel-1 at about 150 pounds, ICEYE-X2 sends back high-quality images with a resolution of ten feet, meaning it can distinguish a vast majority of fishing vessels.

ICEYE achieved these size and cost reductions by combining new off-the-shelf electronics with an intelligent use of trade-offs. Rather than running the power-hungry radar continuously and imaging as much as possible, ICEYE only takes selective snapshots of areas of interest, making it far more efficient.

ICEYE plans to launch 18 satellites with the first five reaching orbit by the end of 2019. By working in teams, this new radar-equipped constellation will do something no single satellite could ever do—revisit the same spot several times a day.

“If you can only see where an iceberg is every two days, you have to rely on current predictions,” says Laurila. “Or you have to operate an aircraft to watch it, and that’s expensive.”

A whole constellation of satellites means that ICEYE can track bergs, or vessels, in near real time. Not only can you spot an illegal fishing boat, you can track it and identify it when it turns on its radio beacon.

ICEYE is working on a variety of improvements to resolution, coverage, and communications, as well as a novel radar sensor that can detect the material of an object as well.

“This will leap forward a generation,” says Laurila. “To compare it with television cameras, this will be like a color camera instead of black and white. “

Origami Satellites and Radio Snoopers

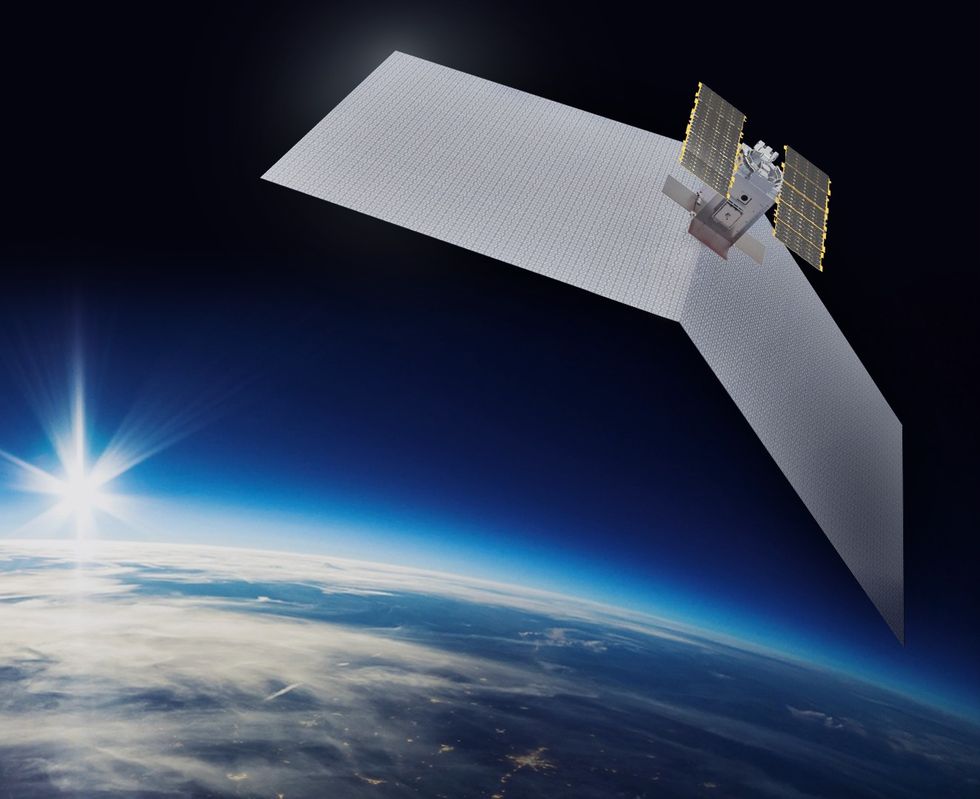

But the same Falcon 9 rocket that launched ICEYE-X2 also launched a competitor, a micro radar satellite from San Francisco–based Capella Space. Called the Capella-1, this satellite weighs in at just under 100 pounds and is about the size of a backpack.

Much like the ICEYE constellation, the Capella satellites deliver what Capella's founder and CEO Payam Banazadeh calls "rapid and persistent imagery" using constellations of satellites to revisit the same spot several times a day. Capella Space aims to have twelve satellites in orbit by 2020.

“Our cost will be an order of magnitude and in some cases two orders of magnitude cheaper than the status quo,” says Banazadeh. “This would allow us to provide better than three-hour temporal capability globally and position us as the most rapid high temporal provider of geospatial information.”

Banazadeh told Popular Mechanics that their satellites benefit from smart power management and innovative design that packs the folding antenna and solar cells origami-fashion into a compact payload, with the ultimate goal of reducing costs by any means necessary.

Going forward, Capella is likely to have even more satellites that are increasingly smaller and cheaper while fusing the radar images with data from other sources, such as satellite photography.

But the ICEYE-X2 and Capella-1 weren't the only imaging satellites onboard this particular Falcon 9. A very different type of space sentinel, a trio of miniature Hawk satellites from Herndon, Virginia startup Hawkeye 360, doesn't use radar at all but instead passively scans for radio emissions including radar, ship-to-ship, and satellite communications. Working together, the three satellites can triangulate and pinpoint the source of signals. Pretty much any ship carrying out fishing operations will be visible and identifiable from its particular combination of equipment.

“Previously this sort of data has only been available to intelligence agencies,” says Woods. “You’ll be able to get a digital fingerprint for each individual ship.”

Hawkeye 360 is currently carrying out mission checks and maneuvering its satellites into position before operations. While Global Fishing Watch may not have access to Hawkeye’s service immediately, its success could create a gold rush of small satellites built for tracking ships via radio.

Putting It All Together

But in order for this new collection of satellites to be useful, Global Fishing Watch will need to merge disparate streams of data into a single view.

“Once you can start layering radar with other data, like photographic and AIS [radio beacon], you start to get a really nice picture,” says Woods. "What was unimaginable just a few years ago is now becoming inevitable."

This new generation of low-cost observation satellites could also transform agriculture, infrastructure, defense, intelligence, and scientific communities, but for maritime policing, it's a whole new era. With nowhere to hide from satellite-based policing, smugglers, traffickers, and pirates will no longer be safe within the boundless blue of the ocean.

The Wild West of illegal fishing will have to deal with a new sheriff in town.