- Artificial intelligence could be throwing off the search for alien life just as much as humans' own cognitive biases, according to a new paper published in the scientific journal Acta Astronautica.

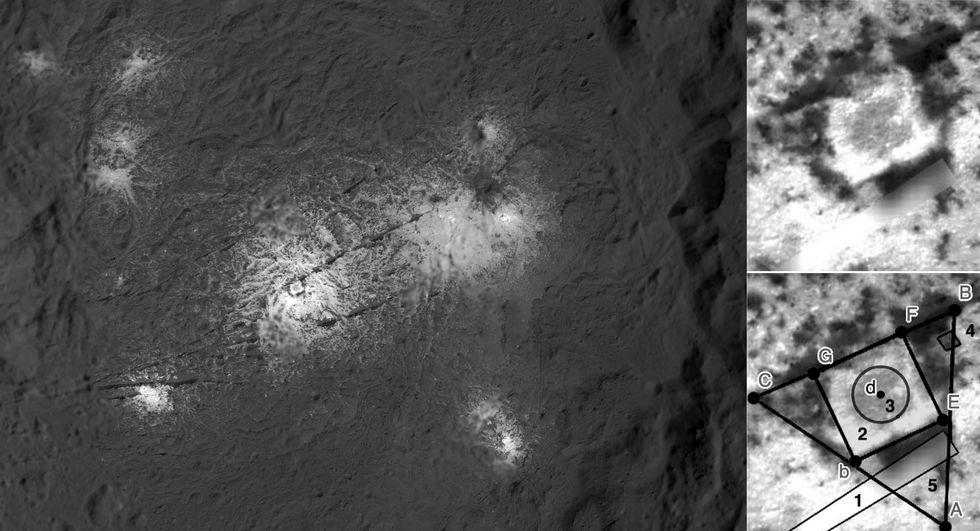

- When a neural network was shown an image from a crater on the dwarf planet Ceres, it identified curious patterns, including both a square (which people also saw) and a triangle.

- After the neural net detected the triangular shape in the images, people in the study also began to see it, even though they hadn't previously. It's an example of how false positives from AI could trip up extraterrestrial studies.

Ever since the Dawn spacecraft picked up images of what look to be a vast network of bright spots in the Occator crater on Ceres—a dwarf planet in the asteroid belt—there's been conjecture over whether the whiteish spots are made up of ice, or some kind of volcanic salt deposits. Meanwhile, another controversy has been brewing over them: What exactly are those shapes seen in the bright spots, called Vinalia Faculae? Are they squares or triangles? Did extraterrestrials create them?

Because the strange patterns are so strikingly geometric, researchers from the University of Cadiz in Spain have taken a closer look at the bright spots to figure out whether humans and machines look at planetary images differently. The overall goal was to figure out if artificial intelligence can help us discover and make sense of technosignatures, or potentially detectable signals from distant, advanced civilizations, according to NASA.

"One of the potential applications of artificial intelligence is not only to assist in big data analysis but to help to discern possible artificiality or oddities in patterns of either radio signals, megastructures or techno-signatures in general," the authors wrote in a new paper published in the scientific journal Acta Astronautica.

To figure out what people thought they saw in the images of Occator, study author Gabriel G. De la Torre, a neuropsychologist from the University of Cadiz in Spain, brought together 163 volunteers who had no prior astronomy training. Overwhelmingly, these people identified a square shape in the crater's bright spots.

Then, the same was done with an artificial vision system trained with convolutional neural networks, which are mostly used in image recognition. Training data for the neural net included thousands of images of both squares and triangles so the system could identify those shapes.

Strangely, the neural net saw the same square the people noticed, but also identified a triangle, as shown in the image above. It appears the square is inside a larger triangle. After the people in the study were faced with this new triangular option, the percentage of them who claimed to have seen a triangle skyrocketed.

It's just one example of how our minds can be easily tricked when faced with a false positive. If we're told a system identified a given blip, we're more likely to blindly believe and truly think we saw the same blip due to our own tendency toward confirmation bias, or interpreting information in a particular way to fit a pre-existing belief.

That makes AI potentially dangerous in the search for far-away extraterrestrial life. False positives can confuse researchers, compromising its own usefulness in detecting technosignatures. De la Torre points out in the paper that what this all adds up to is actually a commonality between humans and AI systems: We both struggle with implicit bias.

So, if not artificial structures, what exactly are those funny shapes in the Ceres bright spot images? The quick answer is "we don't know." But De la Torre has an idea: It's "probably just a play of light and shadow."