“Let’s start,” says Usher, eyes locking onto mine, smile playing on his lips, smooooooooth as you like in his expensive black leather and wool jacket, “by looking at what sexy is.

“Sexy is all in your confidence,” he explains. “But is it in your aura or the way you present yourself, or is it what you have or how hard you work and how you flaunt it? You know, there’s guys who are bigger guys who don’t work out, but what they do have is confidence, and their belief in who they are and in their charisma. The way they talk, the way they move, all those things are very valuable. You gotta build your confidence. Right now, you’re looking at this and wondering, can I do it? Well” — he smiles, geeing me up — “I believe in you, I believe you can. I have done the same. Put yourself out there, take the risk. Try things like yoga, that’s good for you. Or take a dance class, that’s never a bad thing.”

Hang on — yoga? Usher is meant to be explaining how to have sex appeal, and I did have the feeling that it might break down when we moved on from “be confident” to the actual specifics, but I have to say I struggle to see a few hours of downward dog turning me into, well, him. I pause the video, write “Yoga???” on my notebook and hit play again.

The specifics get better now. He starts telling me how to actually talk to women. “Women love a man that can make them smile, right?” he says, smiling but achieving no marks for original insight, “so use that, you know. They love a man who’s charming. Chivalry is not dead, especially in music, if you can use it. But on the other hand...” conspiratorial glance, he’s really warming up now “... you got chicks today that love for you to talk to them crazy.”

I suddenly feel like Steve Carrell in The 40-Year-Old Virgin. Do people really use the word “chicks” without laughing? Usher does. And what does he mean, talk “crazy”?

“You can do that too,” he says.

At this point, the scene briefly implodes, as several people are heard giggling nervily be-hind the camera. Usher sexily cocks an eye-brow, feigns surprise. “What?”

Someone behind the camera says something not quite audible.

“What?”

There is more laughter.

“Well, that’s the truth,” shrugs Usher. “They like that shit.” Then, changing tack, he adds,“But sensuality isn’t the only way to go with entertainment. You could actually be smart. You could have a brain. That’s sexy too.”

I am watching, from the comfort of my own kitchen, Usher’s course on “The Art of Performance”, on MasterClass.com, a website hosting online courses where more than 85 talented people, many of them extremely famous, teach you how to do what they do. It’s a sort of Netflix version of night school, with courses organised into nine categories such as Film and TV, Culinary Arts, Business and Science and Technology and so on.

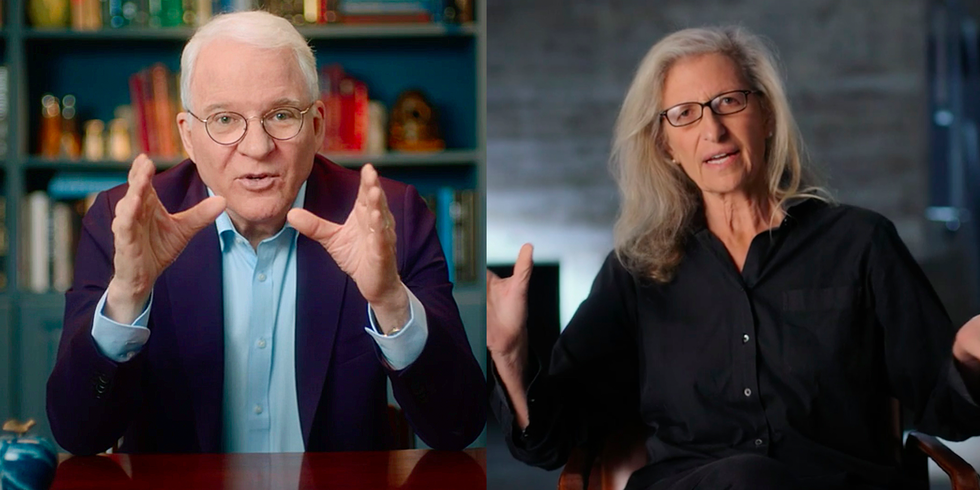

All feature several hours of professionally directed instruction, workbooks full of additional material and access to an online community of fellow students following the course. The range of teachers is impressive, featuring, among others, Steve Martin, Serena Williams, Christina Aguilera, Samuel L Jackson, Annie Leibovitz, Frank Gehry, Aaron Sorkin, Garry Kasparov, Martin Scorsese, Bob Woodward, Alice Waters, Ron Howard and Helen Mirren.

The sequence I’ve been watching is the “Sex Appeal” chapter from the “Creating A Person-al Brand” lesson (“From social media to sex appeal, Usher shares the tools you’ll need to set yourself apart”). Obviously, the idea that I can learn Usher’s sex appeal in a 10-minute video is barmy, as is the thought that Martin Scorsese might teach me to become one of the world’s greatest film directors, or that Gordon Ramsay might turn me into a superchef.

Because of this, MasterClass attracts cynicism from some onlookers, but since the Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, which seemed to ignite a desire for self-improvement in people (remember the bloke who climbed the equivalent height of Mt Everest by walking up and down his own staircase?), subscribers have flocked to pay the £170 annual subscription and the organisation has had a huge spike in profile.

During lockdown in the US, Saturday Night Live ran two “MasterClass Quarantine Edition”skits, one featuring Timothée Chalamet leading a fashion class, the other, cast member Chloe Fineman doing a Britney Spears-as-fitness-instructor lesson.

The people at MasterClass say the lockdown surge means it’s been doing up to 10 times more business than this time last year, and in May the company announced it had raised $100m (£74.8m) in new financing. A report in Forbes hints its income is around $150m (£112m) a year and said the new finance deal reportedly valued the MasterClass operation at $800m (£600m). The eccentric, intellectual CEO and co-founder David Rogier, disputed the figure. It was, he said, “way above that”.

MasterClass is sometimes seen as a blend of American self-help culture and Hollywood glitz with ideas way above its station, but there’s no denying it’s part of a huge global trend: investment in educational technology (edtech) was already high before the pandemic, but this year, when studying and working at home have become part of many people’s daily routines, it has gone stratospheric; the global online learning sector, worth $100bn (£74.8bn), saw record investment of $18.6bn (£14bn) in 2019, and then hit $11.6bn (£8.7bn) in the first half of 2020 alone. We might not all be learning how Usher talks crazy to the ladies, but it looks like there’s lots more online and at-home (ahem) “edutainment” to come.

Like all the others, I started using MasterClass towards the end of the lockdown this summer, when I decided to try to learn to skateboard properly. It felt like one of those things that would ordinarily have been a bit embarrassing, but in lockdown you could excuse with boredom, like dying your hair or drinking heavily during the day, plus there’s an unused, out-of-the-way crumbling tarmac area near my house where no one would see me.

I ordered a basic board and pads on Amazon and took out my MasterClass subscription mainly for the Tony Hawk course, mainly because I’m old enough to remember when he took skateboarding overground in the late Nineties; for some reason this made me feel less ridiculous. (For non-skate fans, Hawk performed the first “900”, a very difficult two-and-a-half revolutions aerial body spin — rotating 900° — at X Games 5 in 1999, and the video clip of him doing so became the first skate footage to really cross over onto mainstream sports television, chiefly via ESPN.)

Despite my partner’s bemusement (“Are you sure? Well, I suppose it’s exercise”) it started off well. Tony had great patter: “I have always said I think skateboarding is a lifestyle, a sport and an art form all at once,” he said in the introductory video, over grainy footage of him skating as a kid. “You’re creating your own style, skating is your canvas, and you can paint it how you want, and no two paintings are going to look alike.”

It sounded an inspiring idea as I followed his extremely easy instructions for foot positioning and not falling over. He also kept stressing the importance of perseverance and repetition, which I took to mean “enjoy my lessons, but don’t think you’re going to be sliding down rails anytime soon — especially you,” but still made trundling round my tarmac feel like an exercise in Zen-like dedication.

When you sign up for lessons, you see a list of videos which can range from around two to 15 minutes long. Each one covers an aspect of the subject in question, and/or an episode from the tutor’s life (Tony has a special section on the 900 which rather encouragingly explains how many times he hurt himself as he tried and failed to do it for years before; Aaron Sorkin mocks up the famous West Wing writers’ room) and you can watch them however you like: all at once, one a week, whatever suits (most people spread them out; Sunday afternoon is the most popular viewing time). You can also choose an audio version with just the soundtrack, if you want to listen in a podcast-like way. In addition, you download a PDF workbook that sets out the content of the course and adds new stuff, and you join a group of members (“Welcome to Tony Hawk’s community!”) that posts on a message board in his section of the site.

Some of the communities work better than others. Usher’s, for example, has people encouraging each other as they post clips of their own music, whereas Hawk’s is a more mixed bag, and not so big on interaction. Most people introducing themselves are humble and friendly enough: “45 years old, NYC. I had just started skating during the pandemic (so cliché!)” writes one man; others are upbeat, “Thanks Tony for a fantastic class! I’m a female anaesthetist that does rock-climbing, sailing, etc and always wanted to get into skateboarding (have done skiing, ice-skating, roller-blading)... Your passion and drive for the amazing sport of skateboarding is super inspiring!! Always loved the music, fashion & lingo of skateboarding ”).

Another subscriber, however, is less impressed: “As if Tony Hawk doesn’t have enough business engagements. Why??? Boring. You could have gotten so many other skateboarders, younger, funnier, with more need for the money.” I suspect “such as, for example, me” might be the silent part at the end of this sentence.

Anyway, I added myself and tried to strike up conversation with Johnny20 from Arizona but haven’t heard back. I suspect for all of MasterClass’s well-intentioned attempts to create a community, for most people it’s about you and the tutor and that’s partly because the tutors add in a lot of empathy-building personal stories; in Tony Hawk’s case it’s hard not to feel some sort of connection as he tells you about the injuries and public humiliations he suffered while trying to perfect the 900.

David Rogier has learned that this style works for the audience. “I think that when someone is really good at what they do and they talk about it, it’s not like they’re trying

to teach you, they’re just sharing what they know,” he tells me on a Zoom call. “There is an authenticity to it, and the superfluousness and pretentiousness just drops. There’s then more openness from your side because they’re sharing their personal experience and you feel you’re learning from it, which is a different thing to being in a classroom and being talked to.

“And then you can hear in their voice that this all came from hard lessons, and your empathy is dialled up. It’s stuff you don’t hear anywhere else, so you want to hear,” he says. “Our education system just isn’t like that. Imagine if instead of trigonometry your maths class had been taught by someone who used maths to engineer a building, and if he didn’t get it right the building would collapse.”

Rogier didn’t particularly enjoy the education system. His Jewish immigrant family originally fled to the US to escape the Holocaust (his grandparents met inside Auschwitz), and he was brought up being encouraged by them to ask questions, to have a point of view on everything. Growing up in Los Angeles, he was always in trouble at school for questioning his teachers, “not in a bad way, I just liked asking questions. But I felt my job at school was to sit in a chair and only speak when spoken to. And I realised at the time that I loved to learn things, but I hated school, and that was... incongruent.”

Rogier speaks very quickly, very articulately, with a stammer he finds frustrating but refuses to be cowed by (that was thanks to his family; they refused to let him use it as an excuse, the default Rogier family philosophy being “if you weren’t in Auschwitz, you’re basically OK.”) You see where the understanding of empathy and hard knocks comes from. He got the idea for MasterClass from his grandmother, who struggled to get accepted into medical school post-war, having been openly told she had three strikes against her: being a woman, an immigrant and a Jew. “She taught me many things, but one I’ll never forget, ‘Education is the only thing someone can’t take from you’.” That, he says, was what spurred him to create MasterClass, with its initial mission to try to “democratise access to genius”.

Before launching MasterClass, Rogier completed a degree in political science and political economy, worked as a manager on the US launch of Tesco supermarkets, did an MBA at Stanford Graduate School of Business, and worked for a tech investor who ended up funding the first MasterClass research. Rogier wanted a platform that provided a new kind of learning experience that was not just about one person educating another, but about allowing people to explore and feel they were finding new perspectives, skills and approaches in their own way.

One method he likes to use to explain the concept is to ask people to close their eyes and picture “education”, then “learning”; for most people, the former involves fairly sterile classrooms, the latter a more emotional experience. He wanted to achieve the latter. He also knew that to really get the profile he required, he would need to have people he could justifiably call the best in the world. He got a break, and his first tutor, through a personal friend-of-a-friend connection to Dustin Hoffman, but the recruitment would initially prove more difficult than he thought.

When he pitched for the first round of money, he found investors were either completely sceptical (“they said the best in the world will never teach; if they do they’ll be horrible at it, no one will want to watch it”) or blown away by the potential. The latter often included people for whom conventional education hadn’t been a success. In 2014, there were enough of them to raise $1.5m — before Hoffman had signed up — and work got underway.

When MasterClass launched, people were invited to sign up to single courses, but when the feedback indicated they were really curious about other instructors, Rogier switched the model to an increased-price, access-all-areas version. It went down well: rather than do one class all the way through, a lot of “members” (MasterClass refers to “members” rather than “students”, likewise “instructors” not “teachers”) love jumping around, often in unpredictable ways: members who begin with sports and games classes usually head over to cooking, those who come to learn about business move on to music.

Once you’re in, you see how it works: maybe it’s because the internet has rewired our attention-paying brain mechanisms, but after just an hour of Tony Hawk, it’s hard not to think, “Let’s just have a commercial break with Usher”, or to think about tea with Gordon Ramsay. It gets a bit addictive going into the intense, close-in focus of the different little universes, from Usher’s sex classes, say, to Ramsay explaining it’s essential to trim long vegetables because “there’s nothing worse than when you’re at a lunch or dinner and you have to negotiate a big long spear of asparagus.”

This is how one night, after spending time with Sheila E deconstructing drum kits and David Sedaris explaining why the best writing subjects are the ones you think you shouldn’t write about, I ended up mainlining Anna Wintour, editor of American Vogue, for two hours. Wintour’s class was cannily titled “Teaches Creativity and Leadership” with the tag line “How to Be a Boss” used in the copious Instagram ads for it. During lockdown it became one of the two most popular classes and has attracted a slightly cult-like status for Wintour’s clear-eyed dedication to winning at life.

The best bit, the hook, is the first class when she describes her daily routine in “Anna’s Day”. This, it turns out, begins with rising at 4am (5am if she has a lie-in), reading all the papers by 6.30am and then going to play tennis at 7.30am. After that, she manages her time with some robust people skills. After footage of her in a meeting with Priyanka Chopra, for example, we see her in her pristine office explaining what to do with those colleagues who don’t share her brisk approach. “Sometimes there are people that come into my office, that... I feel that they are settling in,” she grins a little, and gently chops the air in front of her with her hands, like Gordon Ramsay trimming bothersome asparagus. “I feel... that is not an effective way for them to spend their time.” Fuck yeah, you think, no more listening to Ryan from marketing’s shit jokes!

Of course, the next morning I sleep through the alarm, but I did at least find out by Googling that people really do play tennis at 7.30am, even in London. In fact, there seems to be a whole subculture of empowerment tennis; my local club offers classes called “Will to Win”, so thanks Anna for opening up a tantalising new world for me. Anna, by the way, has a much busier and chirpier community than Tony. Discussion topics include “How Not to Let People Tell You ‘No’”; “How to Deal With Micromanagement When Your Boss Feels This is Correct”; “Share A Powerful Image That Inspires You” and “What Does Anna Mean By ‘Settling In’”?

Rogier spent the first year’s preparation of MasterClass mostly recruiting the first in-structors and working out how to do classes. “It was harder than I expected,” he says. “But that wasn’t because it was hard to persuade them. It was getting to them in the first place because the people around them didn’t think it was a good idea.” Once he was talking to the stars, however, he found many agreed quickly. “I remember Serena [Williams] and Usher being into it straight away. They, like every one of the people who signed, had had someone in their lives who taught them in this way.”

Rogier doesn’t comment on instructor’s contracts, but the individuals are reliably reportedly to earn about $100,000 [£76,000] when they sign up to work with MasterClass, and receive 30 per cent of the revenue their classes generate. Rogier says that money isn’t the only motivation, as many of them see it as a chance to give something back. Nekisa Cooper, the firm’s head of content, confirms this, recalling that Ron Howard, for example, was keen to be involved because at the time he was approached he was planning a book that would allow him to share his knowledge and “send the elevator back down.”

British chef Yotam Ottolenghi, whose own tutorial launches in the autumn, tells me that MasterClass’s starry cast of maestros now means that being asked bestows a bit of cachet, and indeed intimidation. “I thought it was a massive honour when we started talking to MasterClass. The calibre of the instructors is dizzying so I was concerned about delivering that level of teaching.” MasterClass now finds itself being pitched by Hollywood celebs’ agents.

The content and structure of the courses are worked out with the help of Cooper’s team, the process taking anything from “two weeks to a few months”. The team begins by researching what members would like to learn from a particular instructor, and then taking the findings to said instructor and asking if they can teach those areas. It doesn’t always go smoothly, even with experts.

“When we were working on the political strategy lessons with David Axelrod and Karl Rove,” says Cooper, “we went to them with an outline of 37 lessons that gave a really comprehensive picture of political strategy. They looked at it, and said, ‘Wow, amazing, this is a really comprehensive list...’. and then explained they were only experts in about 15 of the subjects. So we focused on those. What we’re looking to do is capture what people are most passionate about. That’s how you get the element of practical wisdom, which members really respond to.”

Appropriate stage sets are constructed and filming is done in three days. There’s no script; the dialogue is drawn out by an interviewer, whose voice is edited from the final version so it appears the instructor is directly addressing the viewer. “Intimate, emotional, relevant” is one mantra, “timely and timeless” is the other: the latter means there’s a noticeable effort to avoid references to specific events and dates in the recent past.

Occasionally, material that should work doesn’t and the approach has to alter. The US gardener and food activist Ron Finley was fine talking to camera about growing plants and making food, but Cooper noticed everyone present was electrified when he told them his stories about planting and growing fresh food in his South Central LA home (Finley is known as the “Gangster Gardener”). So Cooper got him to talk about that to camera too; his class has been one of the biggest hits this year, and, one feels, is a favourite with the MasterClass staff, who mention him a lot.

It’s clear from watching classes that some take to it more naturally than others: Aaron Sorkin is a little bit like your friendly but stiff tutor from uni; David Sedaris is a great raconteur whose table you’d wish to sit on at a wedding party; Martin Scorsese sounds like he’s doing the voiceover for a film in which a kid starts out making movies and ends up in The Mob. With more tutors being added all the time there’s clearly an effective production line, but it may not always be quite as smooth as it looks: in London, a rumour does the rounds that one prominent, contracted musician ran away from his shoot after he suddenly developed stage fright.

When MasterClass launched in 2015 with only a few instructors, Rogier wasn’t convinced it would work, and remembers crying, and calling his parents at the end of the first day because the numbers of people signing up were far short of what he’d expected. But by the end of the fourth day they had increased enough to reassure him. Four months later, 30,000 courses had been paid for, and there were some spectacular stories about tutor-pupil interactions: Serena Williams was said to have invited one of her students to play tennis; James Patterson published a novel with one of his pupils; and it’s thought Deadmau5 has signed one of his learners to his record label Mau5trap.

Rogier likes to say that conventional school is for the first one-third of your life, and MasterClass is education for the other two-thirds. He also notes that as the culture speeds up it’s hard for schools to keep pace with the skills people need, and that teachers in conventional education are now using MasterClass lessons in their own teaching. He says he’d be happy to work with schools on rethinking lessons and teaching.

Schools are weird; not many of us discuss education policy in depth, but we like to talk about our own schooling, and a lot of us think it came up short for us, or for mates, in certain areas. Because of all this, it is tempting to conclude MasterClass is developing a new kind of education for those who don’t, or didn’t, think school classrooms worked for them. After all, it has come out of a decade when it became popular among educational theorists to talk about how people have different learning styles (some may respond to pictures better than words, some prefer to do rather than listen, and so on) and to try to adapt.

There’s a lot in this, though MasterClass isn’t an answer in itself. Professor Stephanie Morgan of University of Kent Business School, a specialist in psychology and online learning, points out that “a lot of the thinking abou tlearning styles is now being debunked. There are all sorts of reasons that some people may not like conventional classrooms and teachers, but my concern with things like MasterClass is that the learning is passive; you’re not going to get the feedback you get from a conventional teacher, you won’t be chased up on the work, for example. At some point, you do need to d othe work. What MasterClass does show is the value people put on expertise and experience.”

Still, MasterClass’s staff do have insights that can suddenly make you think about learning in a new way, like when Rogier points out that conventional educators are “terrified” of entertainment, or Cooper points out how people respond to a sense of intimacy and emotion in the videos, whereas intimacy and emotion are distinctly lacking in school and higher education.

David Schriber, MasterClass’s chief marketing officer, used to work for Nike and Burton skateboards, and has long experience of teaching people to skate, snowboard, and generally “showing people how to do things they think they can’t.”

I ask him, given that a lot of the instructors talk about the need for confidence, how you get someone to go from self-doubt to properly believing they can do things. “Well, in skateboarding,” he says, “there’s this trick called the ‘ollie’, where you seem to levitate off the ground, and it’s like magic. Years ago, I taught kids at skate summer camp, and I showed them the ollie, and they thought it was completely impossible for them to do. It was the point whereI showed them how to do it and they then did it themselves that made them switch.

“They still get in touch to tell me they remember me teaching them that, and it made me realise that the way you make someone confident is to show them something they think is impossible, and then show them it isn’t that hard, and they can do it. Once they cross that line, they can do anything,” he says.

When Schriber told Rogier that story, Rogier said he wanted someone who could teach the ollie, so Schriber got Tony Hawk in. I tried to follow Tony’s instruction to do the ollie, but I never managed it. I kicked down on the board’s tail, I pushed down with my front leg, it didn’t happen; I did manage to fall over a couple of times, which at least made me feel I had some sort of perseverance. In the end, to be honest, I kind of lost interest, and anyway lockdown ended, and I got more self-conscious about people seeing me on the concrete. It was OK; as Tony points out, part of the journey is finding out if you have what it takes, and I found out I didn’t really. But there was another reason I drifted away as well, and that was clicking on the Chris Voss class.

“The art of negotiation” taught by Chris Voss is the second of the two MasterClass courses that blew up in lockdown. Voss is a tough, grizzled, no-fucking-about, former FBI hostage negotiator, and is a full-on cult; talk to other people enrolled on MasterClass, and they’ll ask you if you’ve done his one. People who come in for Ron Finley’s gardening lessons are most likely to move next to Voss on negotiating; it’s the same for people who come in for Bobbi Brown’s class on makeup and beauty. Women have used him to work out how to talk to their male partners; middle-aged dads use him to get closer to their teenage daughters.

Voss teaches the art of negotiation, and his big idea is that a negotiation isn’t a trade-off, it’s a chance for both parties to gain something.“Tactical empathy” is a key concept; you little wonder it did so well when everyone was shut inside their homes with their families. It’s true, it can sound a bit touchy-feely at first, but then he plays tapes of him negotiating with bank robbers during the Eighties, and you start to feel more convinced. He smartly starts with two basic principles that you can learn and copy in five minutes.

The first is “mirroring”, which simply involves repeating the last three words anyone says to you back at them, which makes them believe you’re empathetic and — yes, really —a fascinating person. The second is “labelling“, whereby you describe the other person back to them (“you seem a little frustrated”; “you look pleased”; “you’re settling in”). This makes them talk about how they really feel. I immediately tried them out on everyone I met and, incredibly, no one notices and you suddenly find yourself turning into one of those life and soul people who always seems to know what to say.

Voss was invited to do a class because of interviews with the website’s target consumers— thirtysomethings who are far enough out of college that they don’t have access to any more formal education, but are “far enough down the path of life to think they have a thing called ‘a career’ rather than ‘a job’, and life’s got complicated for them,” as Schriber puts it.

“We were having conversations with people who would almost break down because they had such anxiety about particular things, an done of them was how to make compromises in life, how to negotiate,” he says. “Then one day, Rogier said a buddy of his had just read a book by this FBI negotiator, and when we looked at it, we were like, ‘We need to talk to this guy!’ Before that, I used to joke that my marketing insights guy should be a therapist.”

Of course, I watch Voss partly for the anecdotes about negotiating with bank robbers and hostage takers, just like I watch Usher for his smoothness and Sheila E for the drum kitporn. The truth is that no, of course just watching Carlos Santana’s guitar lessons is unlikely to make you a jazz-rock-fusion superstar, but there’s a lot of basic entertainment to be had out of MasterClass. It’s not just about challenging ideas on education, it’s also sort of reinventing the celebrity interview for the age of self-improvement. What you take away from it isn’t always about a specific skill; sometimes it’s just pleasing, in a time of people fronting supposedly perfect lifestyles and careers on Instagram, to hear people who’ve done well talking about their cock-ups and blunders and broken ribs.

As 2020 closes, MasterClass will implement a rebrand, designed to emphasise the organisation’s “commitment to diversity of thought”, and to reinforce the idea that the members and instructors are “part of a whole system and new way of learning”. The future, says Rogier, will be about expanding internationally, with more languages and more international instructors, greater availability on more devices, and more classes generally. Areas marked for expansion are business, lifestyle and health.

Rogier’s ultimate goal is to have a member go on to be so successful after their learning that they return to become a MasterClass instructor: in the meantime, his dream recruits for the future are Elon Musk, Barack and Michelle Obama and Lionel Messi. They could all choose their own focus; the important thing, as ever, would be to share their process and their wisdom. And as for Rogier himself?

“I just want to keep learning,” he says.“When you stop learning, you’re dead.”

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox

Need some positivity right now? Subscribe to Esquire now for a hit of style, fitness, culture and advice from the experts