Signs point to COVID-19 vaccines slowing viral transmission, not just disease

Researchers say recent findings bode well for vaccines helping slow the spread of the pandemic

After countless hours spent searching for a COVID-19 vaccine appointment, Elizabeth Kostas is days away from getting her second and final shot. And like many San Diegans, she’s wondering what she’ll be able to do next.

“I just look back longingly and with such good memories of hanging out with friends and doing fun things,” said the 69-year-old Carmel Valley resident. “I want to get back to that.”

But Kostas plans to keep playing it safe for now, and will continue to wear a mask, stay at home and avoid traveling. She’s worried about unwittingly spreading the virus to family, friends and neighbors who haven’t gotten their shot yet.

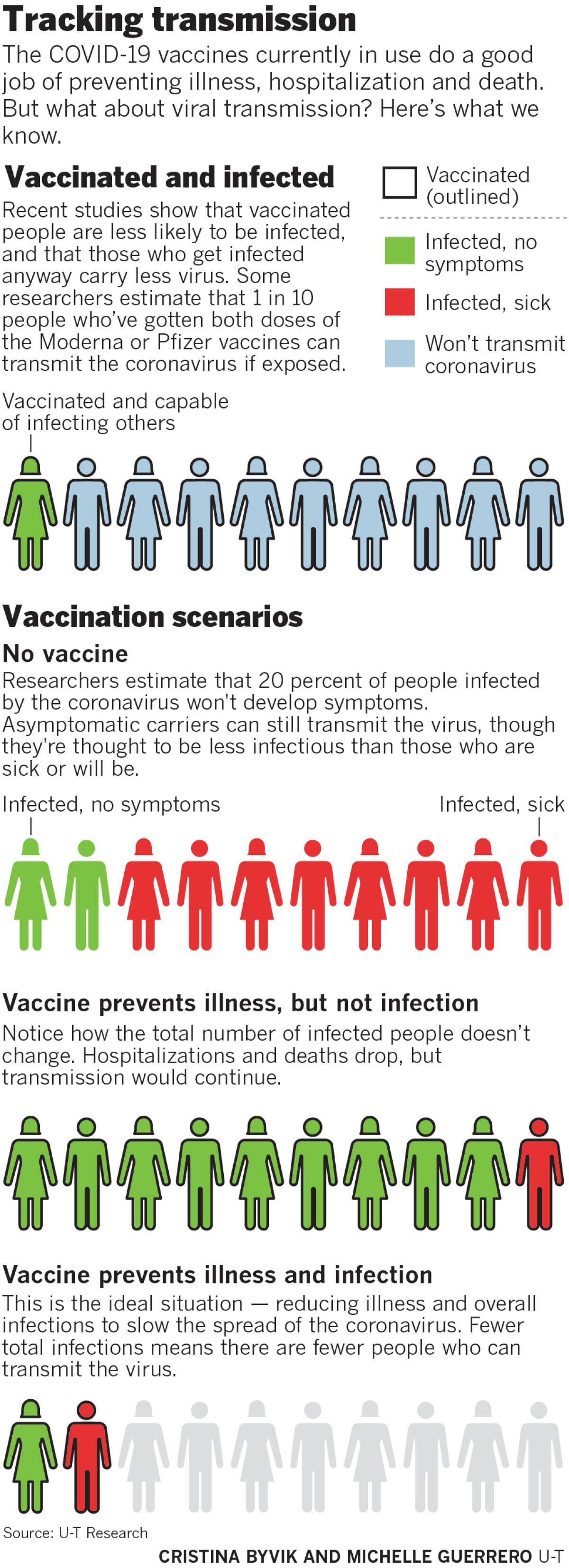

There’s still plenty of confusion and concern around whether coronavirus vaccines protect you from infecting others, but a recent slate of studies suggests that they do.

Scientists stress that the benefits are partial, and that vaccinated people shouldn’t throw caution (or their masks) to the wind. But they also say the information can help people who’ve been vaccinated make safe and sensible decisions about getting together with friends and family — especially if they’ve also been immunized.

“Everyone that’s around a vaccinated person is now getting a benefit (because) that person has a much lower chance of being infected and being able to then pass it on,” said Marm Kilpatrick, an infectious disease researcher at UC Santa Cruz. “That is, I think, the most valuable impact.”

Vaccines are adding a new layer to the risk-reward calculus around the novel coronavirus

The simplest way to show that COVID-19 vaccines reduce transmission is to show they lower a person’s odds of carrying the virus. After all, you can’t spread an infection that you don’t have.

A study posted online on Feb. 22 by U.K. researchers shows exactly that. Scientists tracked more than 23,000 health care workers over two months and tested them for the coronavirus every two weeks, regardless of whether they felt sick.

By comparing health care workers who had or hadn’t been immunized, researchers found that a single COVID-19 vaccine dose was 70 percent effective in reducing infections, and that two doses of the Pfizer or AstraZeneca vaccines were 85 percent effective. Those numbers reflect a decline in total infections — both those that cause COVID-19 symptoms and silent, asymptomatic infections that can spread from person to person.

Even when vaccines don’t prevent infection, they can reduce the amount of virus that you carry. That’s what Israeli researchers reported in early February after analyzing positive coronavirus test results; Israelis who had been vaccinated had an estimated 3 to 4.7 times less virus than those who hadn’t.

That’s helpful considering that having less virus generally makes you less infectious. Spanish researchers tracked more than 300 people with COVID-19 and their close contacts. Those who had lower levels of the coronavirus were less likely to infect family, friends and others.

None of these findings are shocking, says UCSC’s Kilpatrick. But they are reassuring.

“All of us that work on this kind of stuff for a living were hoping we’d get exactly this outcome.”

Kilpatrick has studied the spread of West Nile virus and Lyme disease, among other infections, and his own best estimate is that the current COVID-19 vaccines reduce viral transmission by 90 percent.

That estimate is baked into the models UC San Diego’s Natasha Martin uses to forecast the spread of the pandemic here in San Diego County. The working assumption is that, for every 10 San Diegans exposed to the coronavirus after being vaccinated, only one of them will spread the virus to others.

That’s consistent with the limited local data available. According to Dr. Eric McDonald, the county’s chief epidemiologist, contact tracing efforts haven’t found any San Diegans who tested positive for the coronavirus because they were likely infected by someone who’d been fully vaccinated.

It’s too early to draw firm conclusions from this data, however, given how few San Diegans have gotten the first and second vaccine doses needed to maximize immunity against the coronavirus. And scientists are still learning more about how long immune responses against the coronavirus last, as well as how well vaccines limit the spread of new, faster-spreading viral variants. Still, current evidence all points in the right direction.

Coronavirus statistics from March 2020 to June 14, 2021.

The lingering uncertainty around vaccines’ effects on transmission stems from the COVID-19 vaccine trials being set up to focus on whether the vaccines prevented people from getting sick.

“We decided to go as fast as we can to stop severe infection versus to tease out the answer around transmission and asymptomatic infection,” said Dr. Davey Smith, UCSD’s chief of infectious disease research.

Illness is easier to detect than transmission, and by that measure, the vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna are about 95 percent effective. But around 1 out of every 5 people infected by the coronavirus may never develop symptoms, according to an analysis of current infection data, though they can still spread the virus to others.

Some drugmakers have generated data suggesting their vaccines also limit transmission. U.K. participants in AstraZeneca’s vaccine trial swabbed their own noses weekly, which showed that the vaccine reduced total infections by more than 50 percent. And when Moderna applied for emergency approval of its vaccine in the U.S., it noted that, of the 52 trial participants who had asymptomatic infections before getting their second shot, 38 were in the placebo group compared to 14 in the vaccine group.

Smith is leading a national study that he hopes will go one step further — directly showing that vaccines reduce transmission by collecting data on the household contacts of people who’ve been immunized.

“You’re most likely to transmit to the people you love, and the people you live with,” Smith said.

His team plans to measure antibody levels in vaccinated participants. Their working hypothesis is that people living with someone who has mounted a strong immune response to the vaccine should be less likely to get infected.

Kostas sure hopes that’s the case.

“That’s music to my ears,” she said. “If that comes to be accepted as true, that would be a game changer.”

Get U-T Business in your inbox on Mondays

Get ready for your week with the week’s top business stories from San Diego and California, in your inbox Monday mornings.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.