Homes of the future: the ‘15-minute city’, drone construction, self-cleaning and ‘living’ materials, and hybrid work/home spaces

- Property consultancy Knight Frank’s predictions for future home design in advanced economies show very different living spaces from today

- Expected to see more urban spaces being returned to nature, and innovative materials including cellulose and materials that are self-cleaning and self-fixing

In a Homes of the Future chapter in its 2022 Wealth Report, real estate consultancy Knight Frank predicts that homes in advanced economies could be almost unrecognisable in decades to come.

Referencing the recent video, Singapore 2100, by Singapore-based architectural practice WOHA, the projection expands on the well-accepted idea of “a 15-minute city”, an urban community where everything people need, from shopping to leisure and work, is within a 15-minute walk of their home.

The premise is that, as urban populations grow, the built-environment’s footprint will shrink – a necessity born of the climate crisis.

We’ll be doing more underground, and undersea, freeing up half of the urban space to be released back to nature. Food will be produced on our doorstep (mainly plant-based or cell-grown), all important resources shall be self-generating, and construction will be done by drones and robots.

Fanciful predictions are nothing new, and as Gregory Kovacs, design director at architect firm Benoy points out, rarely do they eventuate. He prefers to look at overarching trends as “an interesting precursor to what may or may not happen”.

Take how the Ford Model T changed how people were living at the beginning of the 20th century, Kovacs offers. “That sparked a movement of people outside cities, and was the start of suburban living in America,” he says.

The warm woods really pop in this furniture store owner’s Hong Kong home

Something similar will happen with autonomous driving, he continues. “The [self-driving] car becomes an extension of the home. You’re no longer just sitting there waiting for the journey to end – you can work on the way, or join a virtual meeting. The car becomes a pod to connect.”

Much else is changing with regard to how people relate to their homes. “With fewer people able to get a start on the property ladder, home-ownership models need to change,” he says. “If you look at Japanese forms for example, the physical space is not very precious, as it’s only temporary – the real value is in the land.

“This could mean having flats furnished in a dynamic way so that a 300 sq ft [28 sq m] space actually functions as a 1,000 sq ft flat.”

That’s perhaps like the hybrid living-working pod dreamed up by fledgling Hong Kong design studio Bagua+Bhava.

Conceived by founder Gavin Leung Hon-chi for a design competition, the pod is scaled to fit in a flat of around 325 sq ft, providing two movable work desks and bookshelves/storage units on sliding tracks fitted to a platform. These movable components may be configured in several ways according to user need, with a sliding glass wall to enclose the space when required. Within the platform is a pull-out bed, an arrangement that maximises space since it’s used only at night. This also frees up room in the flat for general living and socialising.

Leung envisaged the concept, born of the pandemic, as an ongoing solution to the constraints of Hong Kong’s small flats.

“In the future, most will be working from home at least part-time,” he says. “Therefore, a residential unit will be divided in two: one a resting zone, the other a working zone.” His hybrid pod would be made out of plywood mainly for cost efficiency and manoeuvrability.

Agreeing that flats are shrinking and the digital space increasing, Kovacs believes communal spaces are gaining ever more importance.

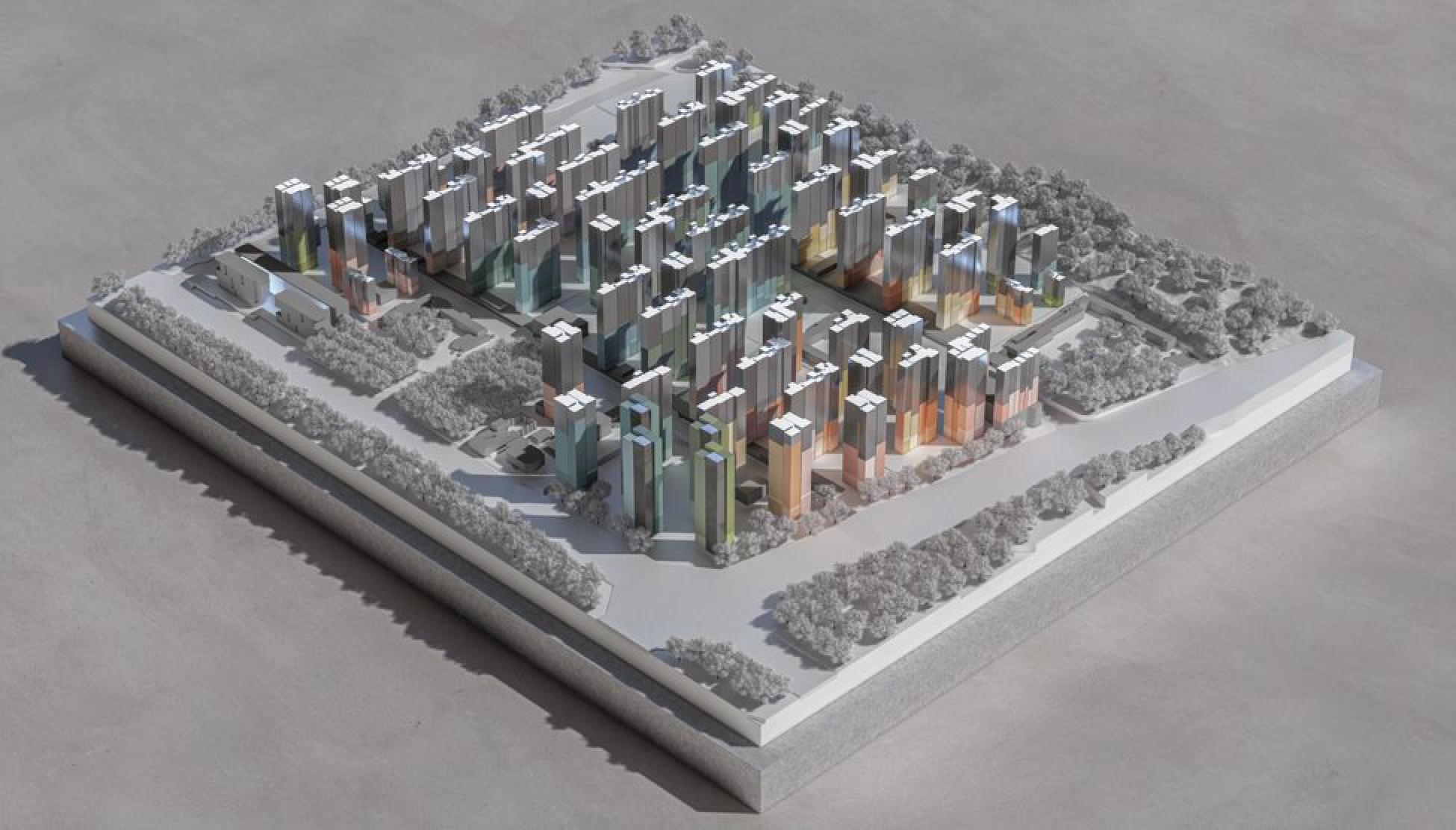

“Right now we are working on an 85-tower residential scheme in Seoul, South Korea [slated for completion in 2023], but the focus of the scheme is not merely the flats but the bottom layer – the ground floor and the surrounding space,” Kovacs says.

He designed one of world’s best hotels. Now comes his most ambitious project

“How can you accommodate tens of thousands of people while still retaining a sense of human scale? It’s about creating communities and neighbourhoods.”

When so many towers all look the same – as is the case in parts of Hong Kong – neighbourhoods can lack soul, having no sense of place, Kovacs adds.

“When we turn the ground plane into a series of streets and squares, you start to create the framework for a place with a unique identity – the feeling of walking from one micro neighbourhood to another.”

Landscaping will become “even more crucial” in tying these spaces together, Kovacs adds, while the towers themselves could contribute by using different colours and design languages for the facades.

Sustainability is another direction gaining traction. For dense Asian cities, this means creating a more compact smart city, not unlike WOHA’s imaginings, but it’s also dependent on moving away from concrete in construction, one of the biggest polluters.

“There is an increasing number of buildings that replace steel and concrete structures with engineered wood, rammed earth or other sustainable solutions,” Kovacs said. “This is a major change that will only get stronger.”

Other innovations include the development of “living materials” made with microorganisms present in their structures – properties that can self-heal (such as repairing cracks in an ageing building) and combat toxins in the air.

One idea, co-developed by researchers at three American institutions -Binghamton University, State University of New York and Rutgers University New Jersey – places fungal spores together with nutrients into the concrete matrix during the mixing process.

“When cracking occurs, allowing water and oxygen to find their way in, the dormant fungal spores will germinate, grow and precipitate calcium carbonate to heal the cracks,” explains Dr Congrui Jin, who is now assistant professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

A suite with a swimming pool? Deluxe urban hotel is given new meaning

Another material being developed, at Holland’s Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), does away with concrete altogether.

Lead researcher Marie-Eve Aubin-Tam says the mother-of-pearl-like composite her team is developing uses cellulose, one of the most abundant biomaterials on earth, synthesised by bacteria. When combined, the bacterial slurry self-assembles into a material with a layered microstructure that is strong and impact-resistant, but its main advantage is the environmental benefit. Aubin-Tam says this material, able to be moulded into different shapes, is recyclable, and shows promise for use in applications such as furniture and construction.

Self-cleaning surfaces are also expected to proliferate. Along with next-generation toilets already on the market that do the dirty work for you, destaining fabrics are under development.

As explained by Andreea Danielescu, lead of future technologies R&D at Accenture Labs, the technology involves treating textiles with a nanoparticle coating that, when hit with visible light, activates a chemical reaction that attacks organic compounds, destroying everything from food crumbs and coffee stains to bacteria.

“The primary benefits would be for high-traffic public spaces – think cinema seating or rideshare vehicles,” Danielescu says. “It could also be useful for furniture in the home, which is more difficult to clean – unlike clothes which can be thrown in a washing machine.”

She believes that with active research and development, technology like this could find its way onto the market in two to three years.

Why a new multistorey skatepark in the UK could work perfectly in Hong Kong

And if another of Kovacs’ predictions is right, many of these innovations might be seen in repurposed buildings – a lo-tech trend already evident that, he believes, will keep gaining momentum.

Benoy has been working on an increasing number of repositioning projects in Asia-Pacific – white elephant buildings that “never originally made sense, or the world has changed, and they no longer meet the requirements”.

One involves a mixed-use development in the Yongchuan district of Chongqing, in mainland China, due to be completed in 2023. After languishing for a decade as “a gaping wound in the city”, the bones of the building are being resurrected as the anchor of a new city centre with a walkable streetscape.

On Fairy Mountain in Wulong, outside Chongqing, Benoy is transforming another half-built hotel. Puzzlingly for a project near a Unesco World Heritage Site, it was originally envisaged to look like a futuristic spaceship landing in the forest – a design Kovacs says “had nothing to do with a relationship with the natural surroundings”.

“Our challenge was to reinvent this project while retaining all the built structures, creating landscape and facade design that seamlessly connects the entire development into the natural context,” he says.

Avoiding demolition was a win for the environment, and when finished later this year the subtle, terracotta-clad hotel will look nothing like the shiny steel extraterrestrial form originally envisaged.

“Made of clay, the facade ties in with both the surrounding nature and the cultural context of traditional Chinese clay bricks and tiles,” Kovacs says. “The articulation of the facade breaks down the scale of the building and blends it with the landscape.”

Kovacs believes that innovation through renovation is the most important direction in crafting cities of the future, including for residential schemes.

“Trying to reuse the old, before building anew, will become the key strategy for improving the quality of our future neighbourhoods.”