From the Editor: Why Is the Lionfish Population Decreasing?

Image: Shutterstock

I first heard about lionfish about 10 years ago when I was visiting Eleuthera, Bahamas. A friend, Maurice White, a talented spearfisher, had become obsessed with hunting them and convincing other divers to do the same. In a few years, he told me, these fish had exploded in numbers and now could be found all over the coral reefs, eating every creature in sight. Maurice wasn’t exaggerating. Since being sighted in the mid-’80s in the Atlantic Ocean, lionfish, originally from the Indo-Pacific region, have spread to the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. They reproduce rapidly, eat voraciously and have no natural predators here. Scientists—and anyone who loves the oceans—were alarmed.

Susan Burns

Image: Lori Sax

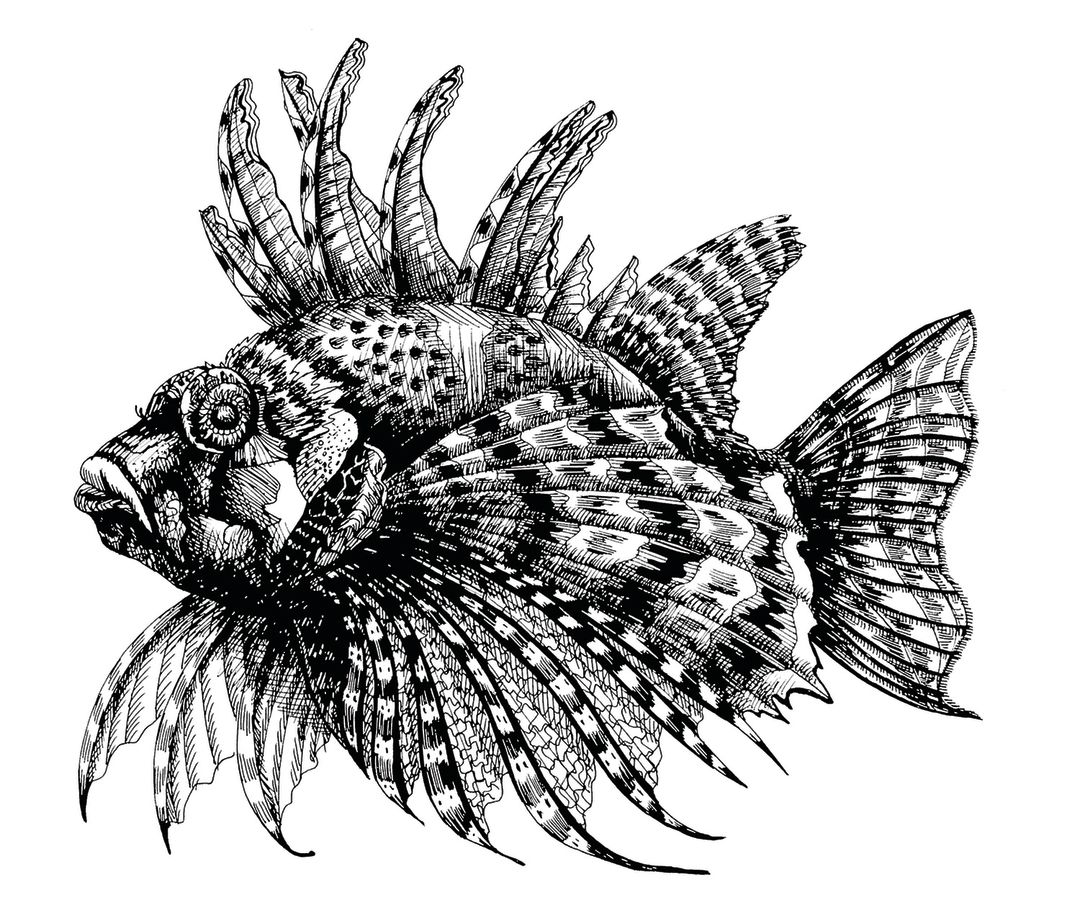

I often saw them when I started snorkeling in the Bahamas. They’re extraordinarily beautiful, with maroon and white stripes and 18 long, showy spines filled with venom. A puncture from one of these spines is said to make you feel as if you’d been hit with a scalding hammer. The pain lasts for hours; some people have to be hospitalized. But because lionfish often remain motionless and are unfazed by divers, they’re easy to spot and spear. They also taste good—mild, buttery and sweet.

It didn’t take long for Florida divers, marine institutes (Mote Marine is one of them) and supermarkets (Whole Foods is a big participant) to organize lionfish derbies, offering prizes to the teams that brought up the most fish. Teams brought up hundreds, sometimes thousands, in a day of spearfishing. Chefs waiting on shore gave cooking lessons and won their own prizes for best recipes. Wholesalers and restaurants bought the catch. Maybe seafood lovers’ hankering for a good-tasting fish would prove to be the downfall of the lionfish.

I called Allie McCarthy, a sales representative at Halperns’, a steak and seafood wholesaler in Orlando, who goes to the derbies, to ask if supermarkets and restaurants were seeing a rise in demand for the fish. What she said surprised me. “We’re having a hard time with the supply,” she said. “Why?” I asked. McCarthy didn’t really know, but said the yield from last year’s derbies wasn’t as large. Then I remembered I hadn’t seen lionfish at one of my favorite reefs in the Bahamas for two years either.

Steve Gittings, a marine scientist at NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries in Baltimore, has been studying lionfish and has designed a lionfish trap for use in deep water that could be used for commercial fishing. “It’s real,” he said about the reports of a drop in numbers. “The abundance is going down where we’ve been looking.” He also said spearfishers and scientists were noticing ulcers on lionfish. Alex Fogg, an Okaloosa County marine resource coordinator who organizes lionfish tournaments, started noticing the decline in lionfish populations 18 months ago. “Reefs that had 100 now have 50,” he says. And, yes, a good number of fish have ulcers on their exteriors.

Neither scientist knows what’s happening, but both say that nature likes to stay in balance. “Most data on invasives is done on land species,” Gittings says, because it’s difficult to track fish in vast oceans. “But [invasives follow] a curve. They ramp up fast and high and then drop off and reach an equilibrium level.” Sometimes the drop-off is caused by predators; or it could be a result of parasites, bacteria or viruses, but the invasive becomes a part of the ecosystem. “Nature often figures out a way,” he says.

Still, he cautions about jumping to conclusions. Lionfish could be proliferating elsewhere. Perhaps lionfish have decimated food sources in certain reefs and have moved. Remote underwater vehicles are reporting lionfish off the continental shelf off Southwest Florida, he says, and agencies need to do more monitoring.

I also wonder if lionfish are victims of human activity. As efficient as nature may be, the world’s scientists are witnessing the disappearance of saltwater fish in all our oceans due to climate change, pollution and overfishing. The decrease in lionfish may end up being just a harbinger of what we face if we don’t back major changes in energy and food consumption. Mother Nature may love balance, but are we reaching a tipping point?