Most Coloradans eschew 3.2 beer — which (for the next few days) can be bought legally only in grocery and convenience stores with specific licenses — preferring instead to buy the “real stuff” at liquor stores. In fact, the biggest market for 3.2 beer may be out-of-staters, especially those who visit ski towns during the winter and stop in those shops rather than an actual liquor store because they don’t know any better.

Dave Keefe knows better. In the early 1980s, Keefe and business partner Craig Caldwell opened Thirsty’s in a three-story brick warehouse along a then-desolate stretch of Wazee Street (now the Auraria Parkway). The rollicking dance club specialized in an unusual niche: ladling out golden pitchers of 3.2 beer to kids between the ages of eighteen and twenty. Back then, Colorado and many other states allowed the younger set to drink beer that was 3.2 percent alcohol by weight — or 4 percent by volume — but nothing stronger, and bars like Thirsty’s, After the Gold Rush and Mardi Gras proliferated, giving high-school seniors, soldiers and college kids a place to dance, to party and, yes, to get drunk in public.

Wednesday at Thirsty’s was “Drown Night,” when you could get two pitchers for the price of one — and it was particularly fun, depending on your perspective. “We would get the Air Force guys from Lowry who would come on Drown Night,” Keefe remembers. “The same ones who would complain that they couldn’t get drunk on 3.2 beer would be the ones puking in the bathroom later.” For the most part, they were great kids, but it only takes a couple to create chaos, and there was often chaos by 11:30 p.m. on Drown Night, when Thirsty’s would begin raising the lights and kicking out hundreds of besotted teens.

The fun came to an end in 1987. That’s when Colorado and a number of other states were forced by the federal Department of Transportation into raising the drinking age to 21 for all alcohol or lose 10 percent of their federal highway transportation funding.

That’s when 3.2 beer should have died. But a funny thing happened: Coloradans kept buying it. After all, it was cheap, easy to find at Safeway and King Soopers, and if you forgot to pick up a twelve-pack for the Broncos game (they went to the Super Bowl that year), it was your only option on Sunday, when liquor stores were required by law to be closed.

In truth, 3.2 beer should have died many times over the past 85 years, for a variety of reasons — particularly numerous legislative changes. It’s possible that no other quirk of Colorado law has caused as much consternation under the golden dome, in churches, in taverns and in bureaucratic offices as 3.2 beer. But it never dried up. Not until now.

At midnight on December 31, 2018, Colorado will finally say a bittersweet goodbye to 3.2 beer; a 2016 law that allows supermarkets to carry alcohol also signed the death knell for 3.2. But the ornery beverage is making sure that it will cause problems even after it’s gone.

Because of the way that 2016 law was written, breweries and beer distributors will still have to act as though there are two separate categories of beer, even though there will be just one. Industry officials are trying to work with state officials and legislators to fix the resulting problems, but it won’t be easy...or quick.

“This is a crazy relic from Prohibition,” says Dan Weitz, a spokesman for Boulder Beer Company, one of the few craft breweries that makes 3.2 beer. “In the grand scheme of things, it was silly, but it’s still here. It’s about time for it to go away.”

Prohibition took effect in Colorado in 1916, and nationwide in 1919. The law, which was championed by an awkward mix of churches, doctors, right-wing nationalists, moralists and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, banned the manufacture and sale of anything stronger than 0.5 percent alcohol. And by 1932, the nation realized that it had been a disaster.

Although widespread alcoholism and its associated social and health problems had been a serious problem in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, people continued to drink with abandon during Prohibition — but now they were doing so in secret. In addition, Prohibition policies had stripped tens of thousands of people of jobs that were desperately needed during the Great Depression, and had also created a violent and sophisticated criminal culture among the gangsters who sold booze illegally.

Franklin Roosevelt ran for president in 1932 on a “wet” platform, and once he was elected, it was clear that Prohibition would end after he took office. Since Prohibition had been enacted by an amendment to the Constitution (the 18th), however, the nation would need to pass another amendment (the 21st) to get rid of it. Doing so would require the approval of three-fourths, or 36, of the 48 states, so that would take a while.

To speed things up, Congress came up with the Cullen-Harrison Act. During Prohibition, “non-intoxicating” beer was considered to be anything less than 0.5 percent alcohol by weight. The new act raised that limit to 3.2 percent, starting immediately. The goal was to get people back to work quickly at breweries, saloons and liquor stores, and to help ease alcohol back into society. FDR signed the bill on April 7, 1933, with these words: “I think this would be a good time for a beer.” And so full-strength beer’s ungainly little brother, 3.2 beer, was born.“These were agricultural towns, conservative towns."

tweet this

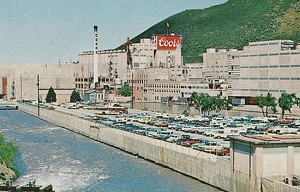

That same day, tens of thousands of people gathered at breweries around the country in hopes of getting their first taste of legally produced beer in more than fifteen years. In Colorado, Coors had been busy brewing since March, and on April 7, it loaded up a train and numerous trucks full of 3.2 beer and shipped them out to Colorado’s thirsty, dusty residents.

The 21st Amendment was eventually ratified in December 1933, allowing full-strength beer, wine and liquor to be sold in whichever towns and municipalities approved of it. Which meant that 3.2 beer was no longer needed...but it didn’t go away. Far from it, in fact.

To prepare for the arrival of full-strength beer, wine and spirits, Colorado had created a new liquor code regulating the sale of anything stronger than 3.2 percent. It forbade the sale of stronger liquor on Sundays or election days, and to anyone under 21; it prevented bars from selling alcohol without food; and it allowed every town to decide for itself whether it wanted to allow alcohol sales. Many municipalities, such as Boulder and Fort Collins, remained dry for decades — aside from 3.2 beer, which anyone over seventeen was allowed to drink under federal law. Fort Collins, which had gone dry in 1896 — twenty years before Colorado and 23 years before national Prohibition — eventually caved in 1967. Boulder followed suit in 1969.

“These were agricultural towns, conservative towns,” says Colorado State University history professor Thomas Cauvin, who explains that the Women’s Temperance Movement, along with the religious groups that had helped push Prohibition nationally in the first place, were still very influential.

Colorado rewrote its liquor code again in 1935, expanding the regulation of alcohol above 3.2 percent. Breweries could no longer own bars, for instance, and wholesalers couldn’t own liquor stores. And because Colorado lawmakers feared that organized crime would continue to control liquor sales even after Prohibition, they included a provision that made it illegal for any business entity to sell full-strength alcohol at more than one location. The same wasn’t true for 3.2 beer, though; it could be sold in multiple locations owned by the same business as long as that business had a license. So, as grocery chains like Safeway, Piggly Wiggly, Kroger and King Soopers began to proliferate in the 1940s and ’50s, they bought vast quantities of 3.2 beer, which they were allowed to sell anywhere, anytime.

These laws created a huge market for 3.2 beer. Anyone who lived in a dry town could buy it. Anyone older than seventeen could buy it. And it was available at just about every licensed grocery, shop and pharmacy — even on Sundays.

By the late 1940s and early ’50s, Colorado realized it had a problem. Newspaper headlines screamed about rampant teenage drunkenness and drunk-driver accidents, and debate erupted over whether innocent-seeming 3.2 beer was actually intoxicating.

In February 1951, the Denver Post ran a three-part series looking at the issue. The first article delved into a proposal by Edward O. Greer, Denver’s manager of safety, that would have cut back the hours during which 3.2 establishments could stay open; limited the number of 3.2 licenses that an operator could own, making it similar to the rules for full-strength liquor; and raised the drinking age to 21. The second article focused on the 3.2 beer industry, which steadfastly denied blame. And the third article analyzed whether you could get drunk on 3.2 beer.

For the first twelve years after Repeal Day, Colorado law had actually stated that 3.2 beer was not intoxicating, until that clause was dropped in 1945. But then in 1951, a district judge ruled in a case brought by a tavern owner that 3.2 beer wasn’t intoxicating; certain “science” at the time had concluded that human stomachs don’t have the capacity to ingest enough 3.2 beer to get a person drunk. The Colorado Supreme Court upheld the judge’s ruling, but later had to clarify that it didn’t mean for the decision to apply to other cases.

Still, that Post article concluded, “it has been 20 years since the largest scientific experiments yet made, and the question is as far from being settled in Colorado as it ever was.”

The series didn’t change public policy, though, and 3.2 beer continued to rise in popularity — at least with teenagers. For adults, it was a different story. In 1963, a group of lawmakers tried to raise the age at which you could buy 3.2 beer to 21 — an effort that met with massive protest and eventual failure. “The 3.2 beer bill, so far the most hotly contested issue of the 1963 session, was killed after some of the longest — and wildest oratory — heard in the Senate,” the Post wrote.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, pressure began building to lower the overall drinking age to eighteen or nineteen, since men of that age were going off to the Vietnam War; the 26th Amendment, which lowered the voting age to eighteen, passed in 1971. By 1975, 29 states had lowered the drinking age, as well. One of the results, however, was carnage on the roads as young, drunk people got behind the wheel in increasing numbers.

So in the early 1980s, Mothers Against Drunk Driving and U.S. Transportation Secretary Elizabeth Dole began crafting a measure that would raise the drinking age back to 21. Since they couldn’t enforce that as a law because of the 21st Amendment, Congress instead passed the National Minimum Legal Drinking Act in 1984. It mandated that any state that didn’t raise the drinking age to 21 would lose 10 percent of its federal highway construction funds."It has been 20 years since the largest scientific experiments yet made."

tweet this

Many states, including Colorado, resisted. South Dakota took the issue all the way to the Supreme Court, where it eventually lost. At that point South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado and other states all raised their drinking ages, even for 3.2 beer. In Colorado, the new law took effect on July 31, 1987, but it allowed anyone who had already turned eighteen by that date to keep drinking 3.2 beer. The result was a three-year death sentence for Thirsty’s and the other 3.2 bars, who knew that they would lose one third of their customers each year until they didn’t have any left.

“Allowing kids to drink 3.2 beer was a great law. It gave them a place to go. They could dance and have a good time,” Keefe says. “A lot of people went out of business when it changed. We lasted as long as we could.” But Thirsty’s finally closed up shop in 1991.

At that point, most people thought 3.2 would disappear — and it probably should have. After all, it had lost the majority of its market. But it didn’t. Not at all.

Colorado’s modern beer wars broke out in 1990. That January, fearing lost sales when the age-limit change finally took full effect, a coalition of 52 grocery and convenience stores, including Safeway, King Soopers, Albertsons, Diamond Shamrock, Mini Mart and 7-Eleven, asked the state legislature to allow them to sell full-strength beer at all of their locations.

The effort got almost no support. The state’s liquor stores represented a powerful lobby of voters and donors, and they warned lawmakers that any changes would result in a push for Sunday sales. They also pointed out that many liquor stores would go out of business as a result.

The supermarket group, which called itself the Coalition for Consumer Choice, responded by saying that customers themselves — not lawmakers — were the ones who might ultimately get a measure on the ballot. “I think it’s coming,” a spokesman told the Rocky Mountain News. “It’s just a matter of time.”

He didn’t know it would take almost thirty years.

Over the next three decades, the liquor stores, who could sell everything above 3.2 percent, and the supermarkets, which could only sell the weak stuff, did battle numerous times. But the gloves really came off in 2008, when then-governor Bill Ritter signed a measure doing away with the archaic 75-year-old Sunday ban on the sales of beer, wine and spirits. That meant that supermarkets and convenience stores no longer had the market to themselves on that day. The chains claimed that they would lose 80 percent of their business as a result — and they vowed to fight back.

That change probably should have put a stake through the heart of 3.2 beer. But as Colorado had seen by then, nothing would kill the little beer that could.

Consumers continued to buy it; some even preferred the lower alcohol content. And by now, they were no longer limited to the light stuff from mega-brands like Coors, Bud, Keystone and Natty Light. A few craft breweries had joined the fray. New Belgium, Boulder Beer Company, Breckenridge Brewery and Tommyknocker all made 3.2 versions of some of their flagship brews for sale at supermarkets.

“Selling 3.2 was an opportunity. Why would we want to miss it?” asks Boulder Beer spokesman Dan Weitz. For some people, he notes, “there is a bit of a snob factor” when it comes to 3.2 beer, but most of Boulder Beer’s brands were “accessible” anyway, meaning their alcohol content wasn’t much higher than 3.2 percent by weight (or 4 percent by volume).

The real power of the craft breweries became apparent a few years later, when they stood beside liquor stores in their fight against supermarkets. Because of Colorado’s odd laws prohibiting chain stores from selling full-strength beer, some craft breweries had been able to carve out a niche at liquor stores without having to rely on grocery-store sales. That allowed some of those little breweries to become larger breweries and to get their products in front of more consumers.

Things finally came to a head in 2015, when legislators proposed a bill that would have made it legal for supermarkets to carry not just full-strength beer, but wine and spirits as well. The measure was defeated, but it left liquor stores and craft breweries bruised. They realized that public sentiment was beginning to turn and that the issue was likely to go to the voters as a ballot initiative, which they would lose.

It was a far cry from March 1955, when the Post reported that six grocery chains, under pressure from church groups, had entered into a “gentleman’s agreement” not to sell 3.2 beer. “King Soopers, Miller’s, Busley’s, Piggly Wiggly, Furr and Save-a-Nickel stores have agreed not to apply for beer licenses and want none of this kind of traffic,” the paper reported. Then again, “the agreement by most of these chains was conditional, that they would not seek licenses unless forced for competitive reasons.”

In 2016, the two sides crafted a compromise, SB 197, that would allow grocery chains and big-box retailers like Target and Walmart to expand from one location with a beer, wine and spirits license to twenty over twenty years. To do that, they must purchase all of the existing retail liquor licenses within 1,500 feet of the business. When it passed, the proposal also did away with 3.2 beer (technically known as a “fermented malt beverage” as opposed to “malt liquor,” with alcohol content over 3.2 percent) as of January 1, 2019.

Then in 2018, lawmakers approved a follow-up measure, SB 243, that dealt specifically with beer and included convenience-store chains like 7-Eleven. After considerable drama that the 1963 Post surely would have considered “wild oratory,” the supermarkets and convenience stores came out on top, gaining the right to sell full-strength beer at every one of their locations with very few limits or regulations.

Jeanne McEvoy, president of the Colorado Licensed Beverage Association, which represents independent liquor stores, prefers to put a positive spin on the situation. “We agreed to this change. We didn’t get everything we wanted. But neither did they,” she says, adding, “There will be a new normal. But we still have wine and we still have spirits.”

But 3.2 beer isn’t done with Colorado yet.

After Governor John Hickenlooper signed SB 243 into law, state regulators realized that its language created a few glaring problems.

The first was that any brewery that wanted to sell to supermarkets and convenience stores in 2019 would have to apply for and receive a 3.2 “fermented malt beverage” license, even though 3.2 beer will no longer exist as a category. The second was that breweries and wholesale distributors would have to identify which beer was going to liquor stores and which was going to a supermarket, and keep the “fermented malt beverage” separate from the “malt liquor” in the breweries, in warehouses, on invoices and on trucks.

“Unfortunately, the way the law was written, they never dealt with the issue of collapsing the two licenses,” explains Andres Gil Zaldana, executive director of the Colorado Brewers Guild. “So every brewery has to get a fermented malt beverage license and sell to a FMB wholesaler. It’s a silly fiction because we all know that the definitions are now the same as of January 1.”

Craft breweries panicked over the licensing snafus. Although most small brewers had initially opposed supermarkets gaining the right to sell full-strength beer, many had decided to dive into the market once the laws changed. But applying for a FMB license is a long and expensive process. To make things easier, the Colorado Brewers Guild worked with the Colorado Department of Revenue’s Liquor Enforcement Division to come up with a cheaper, faster way. “The LED doesn’t have the power to collapse the licenses — only the legislature does — but they were able to create this fast-track process back in October,” Zaldana says. Nearly forty breweries took advantage of the new process, while others continued to follow the old approach.“We’ll be focusing on craft. Colorado local products have always been a focus of ours.”

tweet this

The second issue won’t be as easy to correct. Even though all of the beer that is brewed will be the same, the stuff that ends up in grocery and convenience stores has to be identified as fermented malt beverage for legal and tax purposes, and it has to be stored separately and transported separately. That means a truck delivering to Safeway can’t also go the liquor store. “On January 1, beer is beer,” says Steve Findley, president of the Colorado Beer Distributors Association. “But in the eyes of the state, it is still two different products.”

As a result, Findley’s group and the Brewers Guild are working with Hickenlooper and state legislators to come up with an emergency bill that would fix the language in the flawed law. In the meantime, the LED has pledged not to enforce that provision of the law until February 1.

That will certainly be helpful for the three dozen or so craft breweries and their distributors that plan to drop off truckloads of full-strength beer at hundreds of grocery and convenience stores on January 1. Most of these stores have already made room for the beer (though they aren’t allowed to store any of it until the new year), scooting other products, including big 3.2 brands such as Coors, Miller and Bud, over to the side.

“We’ll be focusing on craft,” says Gregory Junk, the Adult Beverage Category Manager for King Soopers in Colorado. “Colorado local products have always been a focus of ours.”

Most of his 185 stores will carry a set list of specific beers in addition to some selections from breweries that are near each individual store. While each location will likely have New Belgium Fat Tire, Odell 90 Shilling, Oskar Blues Dale’s Pale Ale, Avery White Rascal, Great Divide Denver Pale Ale, Dry Dock Apricot Blonde, Ska Modus Hoperandi, Boulder Beer Shake Chocolate Porter, Left Hand Milk Stout Nitro, River North Colorado IPA, Upslope Craft Lager and Denver Beer Co. Princess Yum Yum, stores in south Denver might also carry beers from Lone Tree Brewing, Copper Kettle and Saint Patrick’s, while stores near Boulder could carry selections from Sanitas Brewing and Odd13. Stores in Durango, meanwhile, are likely to have several selections from nearby breweries such as Ska and Durango Brewing.

The goal, Junk says, is to carry 60 percent craft and 40 percent domestic. Eventually, big brewers like Coors and Bud may get rid of their 3.2 brands altogether, he predicts; of the five states that still allowed 3.2 beer last year, Oklahoma and Colorado have now switched, and Kansas will soon follow. That leaves only Utah and Minnesota.

That doesn’t mean that low-alcohol beers will disappear altogether, however. Most of the big beer brands already sell selections that are only slightly higher than 3.2, and craft breweries have continued toying with lower alcohol beer. New Belgium, Upslope, Boulder Beer, Odell and others already offer beers that are very close to the lower limits.

And despite the assurances of Junk and other beverage managers, many craft brewers still fear that the supermarkets will eventually revert to sales of big domestic brewers, or will rely on major out-of-state craft brands, such as Sam Adams, Lagunitas and Sierra Nevada, leaving Colorado out in the cold and out of the coolers.

However it shakes out, 2019 will certainly ring in a new era of beer drinking for Coloradans. As FDR said back in 1933, “I think this would be a good time for a beer.”