The secret to long life or early aging is… poop?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Jennifer Garner’s character in 13 Going on 30 — Jenna Rink — wishes she could age more quickly. The ills of being a teenager and navigating social structures in the late-'80s are too heavy to handle and, through the power of wishful thinking and some magic dust, she gets her wish. Being 30 without the knowledge of the intervening years, however, isn’t easy either. Eventually Jenna finds herself wanting to be a kid again.

That’s something many of us can probably relate to. When you’re young you wish you were older, and when you’re old you wish you could reclaim your youth. The secret, it turns out, isn’t magic wishing dust… but poop. More specifically, it’s the microbiota found in your digestive system.

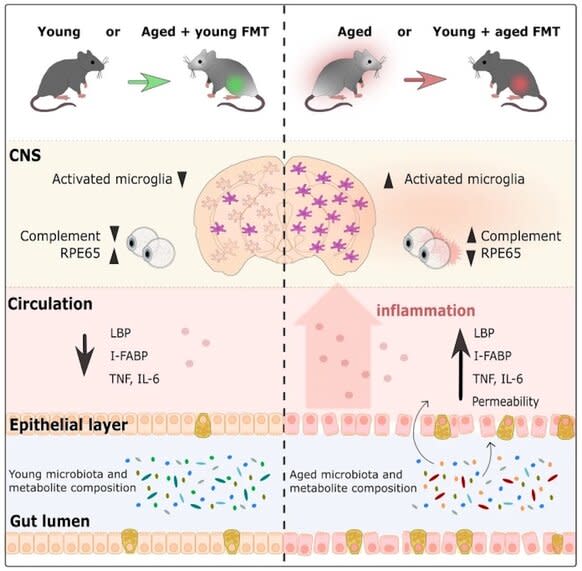

Aimée Parker from the Gut Microbes and Health Research Programme at the Quadram Institute, and colleagues, recently completed a study looking at the impacts of microbiota transplants in mice. In short, they took fecal materials from young mice and transplanted them into old mice, and vice versa, to see how their physiology was impacted. Their results were published in the journal Microbiome.

“We did a transplant of fecal slurry that’s spun down resulting in essentially fecal water. It’s got most of the bacteria in there, as well as viruses and fungi, which we didn’t specifically look at,” Parker told SYFY WIRE.

Photo: Aimee Parker et al/Microbiome

The study was relatively short-lived, lasting only a few weeks, but researchers saw significant changes in the mice who received treatment. Older mice who received gut microbiota from younger counterparts experienced reversal of several age-associated deteriorations, including cognitive function and changes to the retina. In young mice who received transplants from older mice, the reverse relationship was observed. The mechanisms by which specific microbes impact the body at large aren’t fully understood, but researchers have a decent idea of what’s happening.

“Some microbe species tend to be associated with lowering inflammation or lowering obesity. They have a reputation of being the good guys. We also saw a reduction in the old mice in some microbe species which are considered pathogenic or detrimental,” Parker said.

Moreover, it’s increasingly understood that the gut microbiome maintains open lines of communication with the brain, by way of a vast network of neurons traveling from the gut to the brain. Some microbes are capable of manufacturing neurotransmitter homologues which activate nerves in the gut before making their way throughout the body and to the brain, which is just one way microbes communicate with the rest of the body across vast biological distances.

Another potential mechanism involves metabolites the microbes produce or other microbial products which contain proteins or RNA that later get into the bloodstream, as well as impacts on the immune system driving or reducing inflammation, all of which can contribute to the collective experience of aging.

Because the study only lasted a few weeks, it isn’t certain that fecal microbiota transplants have a longstanding impact on longevity, but previous studies in other animal models suggests it could. What is clear is that, at least in mice, swapping out the microbiome can extend health, if not actual lifespan.

“We wanted to know if we can keep animals — and ultimately people — healthier for longer. Maintaining better eyesight for even a couple of extra years would be hugely beneficial,” Parker said.

The research isn’t yet ready for human clinical trials but human gut microbiota changes as we age, similarly to what’s seen in mice. The types of microbes and their diversity decreases as we age and certain neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s exhibit different microbiota compositions than healthy controls. As uncomfortable as they might sound, fecal microbiota transplants could improve the quality of life and potentially the duration of life, if these effects are borne out in humans.

“I would say, with an abundance of caution, that I wouldn’t recommend anyone runs out, grabs a young person, and makes a fecal smoothie, but it’s not completely unreasonable to think it might be effective. We just don’t know yet,” Parker said.

In fact, if we’re patient, we might be able to avoid the microbiota transplant altogether. Researchers are hoping to identify the specific species of bacteria and the mechanisms at work in hopes of culturing just those species or developing drugs or therapies which would have the same effect.