Every night he goes to gay bars in Portland, Oregon, Justin Riel, a 39-year-old Filipino immigrant who works as a data manager for local courts, gets hit on by white men. Sort of.

“They assume I’m Latino and I have a monster dick,” he said. Upon learning he is Asian, the shift is sudden and stark: “Their face gets disappointed. They say, ‘Oh, I thought you were Latino.’ And then they just walk away.” He can’t count how many times it’s happened—at least once or twice a night, maybe 10 times a week. One hookup, he said, lost his erection when he learned Riel is Asian.

Portland is the whitest big city in America. Riel knows it. “I’ve been here since 2005, but I haven’t dated much,” he said. “It’s difficult.” He has considered medical procedures to give himself chest hair and a longer, thicker penis. Perhaps the strangest part of Riel’s experience is that science says his social life should be more comfortable, or at least more accepting.

A 2019 study—actually a pool of four studies—in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science determined that Asian-American men are seen as “more American” if they are gay. That science recirculated among the gay community this year as new light was shed on Asian-American identity amid a national spree of anti-AAPI violence. This is the same anonymous American public that 42 percent of, when asked in a May survey to name any Asian American, replied with the most popular answer: “I don’t know” (followed by the answers “Jackie Chan” and “Bruce Lee”).

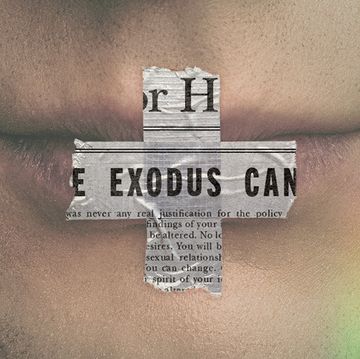

With this urgency to define their own experiences and the beginning of the demise of code-switching, gay Asian-American men are asking questions despite such mixed signals—or perhaps because of them: What does being more American really mean? What is Asian enough? How can queerness reconcile its “no Asians” habit? And, above all, what comes next? Racist tropes are being destabilized, but the question of identity remains murky.

“White gay men look at me as a refugee,” said Kenrick Ross, 41, who is Indo-Guyanese and the executive director of the National Queer Asian Pacific Islander Alliance. He described a curdled version of what it is like to be considered “more American.” “Your parents must’ve been horrible. Your church must’ve been horrible. They must not accept you. They must hate you. But here’s a mostly-white gay world that wants to welcome you. It’s almost like, to live your life openly, you’ve entered American society. People want to hear our sob stories of how terrible our cultures were and how terrible our countries are and how we got liberated by American freedom.”

Ross’s experience speaks to a reality common among more than a dozen gay Asian Americans Esquire interviewed, all of whom flagged that though they have found joy and success, it blossomed from toxic soil.

Lou Miller, 44, a doctor in Brooklyn and a Korean adoptee who was raised by Jewish parents in Philadelphia, grew up wanting to be anything but Asian. “I would often forget that I was Asian, honestly, and that’s kind of what I wanted,” he said. “In the summer I’d get dark and I’d think, maybe I’m part Black. Maybe my father was in the U.S. military in Korea. And that would be great, better than being Asian—to be mixed, to somehow have a claim to America, actual roots here.”

Like many Asian-American men, Miller was disappointed by gay bars and the bigotry he eventually found in those self-ascribed temples of acceptance. He said he only ever got hit on by older white men who seemed to fetishize Asians. “Being a gay Asian person, you accept it as your reality,” he said. “There was a meme going around recently: How old were you when you realized you weren’t ugly, you just weren’t white? That hit me. I spent a long time not wanting to be me, not worthy of attention or love or desire. I did not feel attractive in any kind of way. Now I’m married and I still think, in moments, that this is all too good to be true.” He calls his life a “charmed” one, with a caveat: He feels he is tolerated by both the gay community and Americans at large from “the distance of a hyphen.”

A minority upon a minority, gay Asian-American men describe a lot of overlap in their identities: Both sides of that intersectional identity are affected by enclave living (in either ethnic neighborhoods or gayborhoods), presumption of crazy rich lifestyles despite extreme wealth disparity for both Asian and gay Americans, and a sheen of emasculation that was infamously caricatured in a racist national magazine spread from 2004 that asked of its readers, “Gay or Asian?”

Get unlimited access to 85+ years of award-winning journalism. Join Esquire Select

“It has always been a strange time to be an Asian-American male or masc-identifying person, because you’ve never been given the agency to own your identity—ever since the 1800s and the Yellow Peril propaganda tool to emasculate the Asian-American male. It was very deliberate and very successful,” said David Yi, 34, a Korean-American writer in Colorado Springs who created the Very Good Light masculine beauty blog and authored the book Pretty Boys. “You wake up every day feeling fury, feeling helpless, that your life has never meant anything to this country. So a lot of Asian-American men see that they have to survive by being hyper-violent or hyper-macho or hyper-sexual to outweigh what cards they’ve been given.”

Navigating such territory as a queer man is awkward. Consider George Takei, who called Star Trek’s adjustment of Hikaru Sulu to be gay a “twisting” of the show’s original vision. Or the way Queer Eye’s season in Japan steamrolled the Fab Five’s aesthetic over anything culturally specific. Highlights—like poet and novelist Ocean Vuong’s poignantly messy sex scenes in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, or the tender shower scene in last year’s Taiwanese gay romance Your Name Engraved Herein—are few and fleeting. To whatever extent Harvey Milk and Matthew Shepard are household names, they’re far ahead of Vincent Chin or Fred Korematsu.

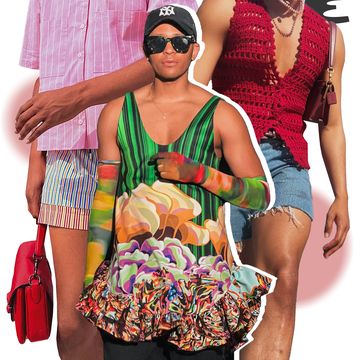

This year Paul Dien, 40, a marketing executive in Los Angeles whose parents are ethnically Chinese refugees from Vietnam, became the It Gets Better project’s first new board president since it was founded in 2010. Citing homophobia in the Asian-American community and racism in the LGBTQ community, he explained his strategy of countering both with what he calls “joy [as] my form of resistance.” “It’s about being yourself but also understanding that you’re part of a fabric of a community that is very diverse. There’s no prescribed notion to being gay in Asian America, but we need community and connective threads,” he explained. He wants to champion what he calls “an emergent, young, progressive, queer Asian American who doesn’t play by the rules,” adding, “I feel like I grew up in a different era. What it means to be queer now doesn’t subscribe to the cisgender white male ideal of beauty.”

That is a relief to Joey Wasserman, 35, a Hong Kong adoptee raised by Jewish parents who owned a gay bar in Philadelphia. (He’s now senior director of development at SAGE, an advocacy group for gay elders.) “In a country that is founded upon diversity, identity barriers are hard. This past year has elevated that for sure,” he said. “I’m Asian, but I would say I belong to the gay community. I wouldn’t say I’m part of the Asian community. The most Asian thing about me is my love of Chinese food and dumplings. I mean, I went to Jewish summer camp for 15 years. I was the only Asian there—and Hebrew school. To be honest, I feel more Jewish than Asian.”

Roy, 55, a Filipino-American actor in Los Angeles who spoke on the condition that his last name be withheld, quit gay nightlife for years, he said, once he aged out of being an Asian twink. But recently he joined a sex party called DILF. “I went to one and, wow, a third of the guys were Asian. And more open-minded, non-Asian men,” he said. “All of a sudden, the daddy is now a preference. I’m the center of attention! Before I was insecure, now I’m not.” He added that he identifies more as a daddy these days than as Asian American.

It seems some gay Asian-American men across generations are leaning into a sense of belonging by birthright and all the brash confidence it gives them, at a time when what it means to be American and what it means to be gay are escaping the grip of white hegemony. In music, K-pop boy band BTS has transformed the aesthetic of teen heartthrobs. In film, Henry Golding’s Snake Eyes and Simu Liu’s Shang-Chi are giving Asian men A-list status as action-packed sex symbols, while Randall Park in Always Be My Maybe serves rom-com charm. And on television, gay Asian characters have swung from the smoldering Nico Kim on Grey’s Anatomy to Bowen Yang’s iceberg on Saturday Night Live.

Everyday rebuttals to old patterns can come in forms as unlikely as Cody Silver, 29, a Chinese-American sex worker in Brooklyn who joined OnlyFans last year and quickly became porn star Cody Seiya. “The main character of Interior Chinatown thinks of himself as a guest role. We can be the lead characters in our own lives,” he said. “I might as well be the representation I want to see and haven’t seen before. I don’t just perform gay Asian sex. I reveal gay Asian intimacy. You don’t see intimacy that often. This Asian guy is getting fucked doggie-style, no kissing, so robotic. It can seem so cold.”

Or New York legal analyst David Lat, 46, a Filipino-American husband and father, whose family became what his friends call the first “white picket gays” in his suburban neighborhood. “I feel more interesting than the typical suburban family. It makes us stand out,” he said. As opposed to Asian dads, he added, “I don’t feel like people have much of an expectation of gay dads. In some ways, what we do will become the model.”

Or D.C. chef Jon Pham, 33, the Georgia-born son of a Vietnamese refugee, who despite not knowing much about his Vietnamese heritage is seen as the “token Asian guy” among gay social groups. He is excited to break through these prescribed stereotypes. “We’re all acting out of some level of insecurity or hurt when we’re hurtful and hateful and judgmental of other people,” he said. “It’s certainly not coming from a place of understanding or love or support. It requires compassion, empathy, and understanding to get there. And self-reflection. If I’m stereotyping other people, what am I shutting out?”

These men all described isolating existences, but see themselves more as pioneers than pariahs.

However change does arrive for them, it is a political act. So perhaps it’s no surprise that a gay Asian-American politician has made some of the most tangible progress in defining his own identity within a diverse coalition of allies. When Sam Park, 35, a gay Korean-American state legislator, became the first Asian member of Georgia’s legislative body in 2016, there were three other out queer members. “Being a minority within a minority has certainly made me more empathetic to the struggles of feeling invisible, being a marginalized community,” he said. “There are challenges. But therein lie opportunities that allow for greater understanding, and the capacity and ability to build community.” He is currently in his third term, and there are now five people of Asian decent and seven queer people in the legislative body.

Park is also proudly Christian. The queer mantra of “love is love,” he noted, is not so distant from the evangelical crux that “God is love.” Perhaps hyphens can also be bridges and bonds. Maybe gay and Asian lives should not be measured in terms of being more or less American, but rather more or less kind. More or less empathetic. Those kinds of attraction transcend the merely erotic.

“One of the highest moral imperatives derived from my faith is love—treating your neighbor as yourself—which has certainly been a grounding, foundational pillar in viewing public policy,” said Park. “Whether as an Asian American or as a member of the LGBTQ community, if I want to be free from discrimination, to live free without being attacked for who I am, then I want to ensure the same for my neighbor.”

Can he get an amen?