Scientists have discovered that humans, unlike our Neanderthal cousins, evolved the ability to meditate to deal with both past and future stresses.

Humans and Neanderthals share an important evolutionary stage with the development of parietal lobes.

The key progression awakened the capacity to pay attention and live in the moment, but it has emerged that only humans (Homo sapiens) went on to expand the advantage to the point where individuals had conscious control of their minds.

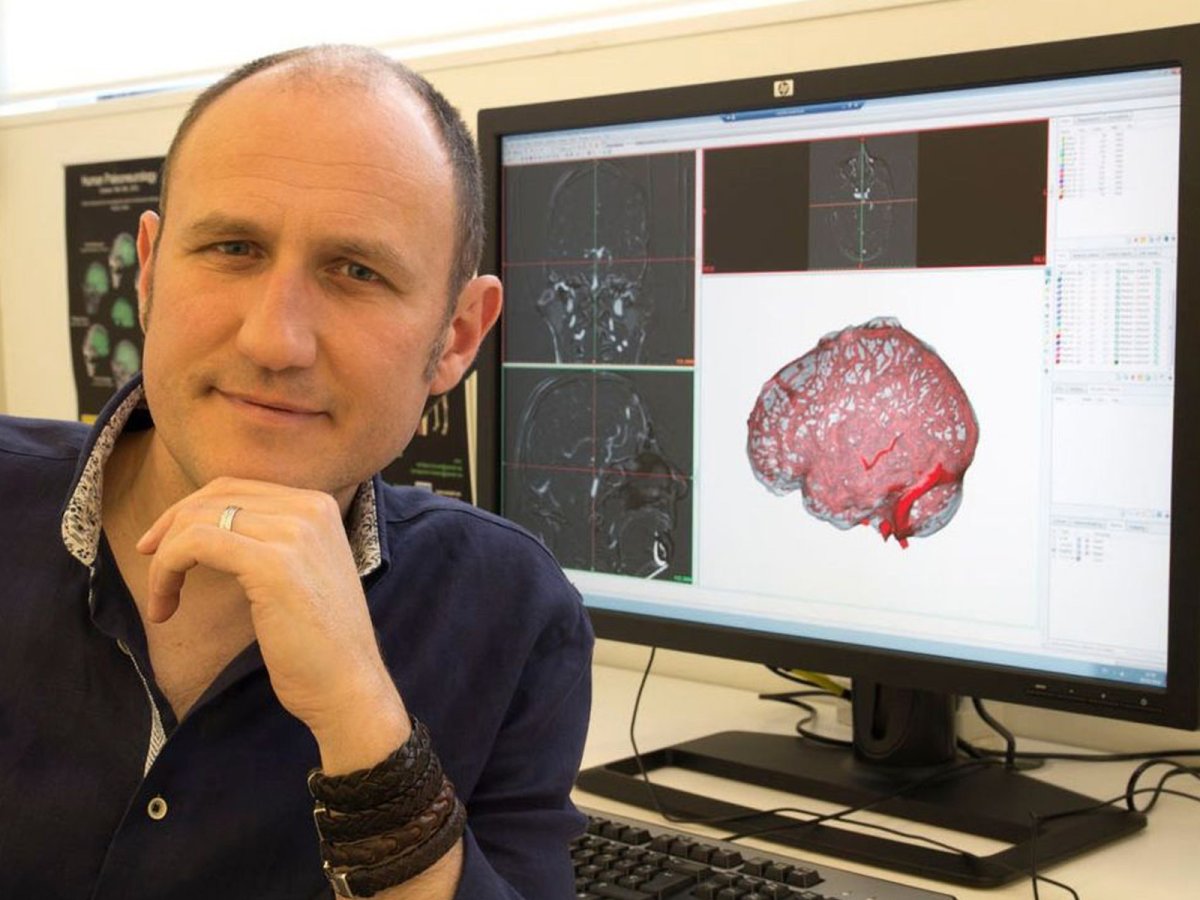

The study, led by Emiliano Bruner, a paleoneurobiology researcher at the National Research Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH) in Burgos, Spain, and Roberto Colom of the Psychology Department at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM), was published in the scientific journal Intelligence.

Bruner combined techniques from archaeology and paleontology to study the evolution of the brain.

The study shows that changes in the brain's parietal lobes were very subtle in Neanderthals who had a highly developed ability for attention.

This attention span reached maturity in modern humans who experienced a huge change in the size of their parietal lobes.

Researchers explained that attention is a determining factor for intelligence as it allows us to coordinate different mental processes over time despite external distractions.

The study of the evolution of the parietal lobes, an important part of the attention network, allowed researchers to determine their impact on the ability to stay focused on one objective over time in the face of internal and external distractions.

Bruner said: "Considering the close relationship between attention capacity and meditation, and to set the cat among the pigeons, it occurred to us to investigate whether extinct hominins might have been capable of practicing the selection and maintenance of mental stimuli."

The parietal lobes are related to our visual imagination and ability to project the past as memories and the future as predictions.

A mixup between these projections and the attention network can cause an imbalance between the present moment and internal thoughts which causes stress, anxiety and depression.

They also looked at the ecology and tools of Neanderthals to decide which behaviors suggest evolutionary changes in working memory and visuospatial abilities.

Bruner explained that it is impossible to conclude that Neanderthals had the ability to meditate as they did not have the same stress and anxiety as modern humans because their attention was centered on the present and did not jump between the past and the future as it is the case with modern Homo sapiens.

Meditation or mindfulness trains the perceptual and attention system and is studied in neuroscience for its ability to keep attention focused on the present.

This story was provided to Newsweek by Zenger News.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.