Abstract

A straightforward fabrication technique to obtain patterned substrates promoting ordered neuron growth is presented. Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) single layer graphene (SLG) was machined by means of single pulse UV laser ablation technique at the lowest effective laser fluence in order to minimize laser damage effects. Patterned substrates were then coated with poly-D-lysine by means of a simple immersion in solution. Primary embryonic hippocampal neurons were cultured on our substrate, demonstrating an ordered interconnected neuron pattern mimicking the pattern design. Surprisingly, the functionalization is more effective on the SLG, resulting in notably higher alignment for neuron adhesion and growth. Therefore the proposed technique should be considered a valuable candidate to realize a new generation of highly specialized biosensors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since its first discovery1, single crystal graphene has attracted much attention among scientists as an ideal candidate for a next generation of electronic devices2 due to its completely new, exotic, Dirac-fermions characteristic in quantum transport. At present, research grade highly crystalline SLG is typically obtained via mechanical exfoliation of highly ordered pyrolytic graphite (HOPG), resulting in single flakes of limited useful area and low reproducibility, which are, however, still large enough for electron transport experiments and for a comprehensive physico-chemical characterization. While current efforts are mainly focused on the synthesis of large-area single crystal SLG3, polycrystalline SLG with sizes up to some centimeters is already commercially available on several insulating and conductive substrates and is thus compatible with large area parallel lithographic4 and direct writing processes5. This material is characterized, however, by a high occurrence of defects and grain boundaries, resulting in poor quantum transport properties. This commercial SLG, nevertheless, exhibits peculiar optical, electronic and mechanical properties6. SLG is highly transparent in the visible range with an absorption of 2.3%, with a pronounced absorption peak reaching ~10% in the ultraviolet7; it is highly conductive and its properties are not affected by mechanical stress, making it an improved alternative to commonly used inorganic transparent materials, such as indium tin oxide (ITO) or aluminum doped zinc oxide (AZO). Moreover, its high mechanical resistance allows for easily handling and transferring atomically thin sheets directly onto a variety of technologically interesting substrates, such as flexible polymers, glasses, quartz metals and semiconductors8. Among these, glass substrates are of great interest for the electronics and opto-electronics industry due to their insulating properties, high electric breakdown field and transparency, but also for optics and optical microscopy. It can be also noted that the electrical properties of SLG are particularly sensitive to surface charge, making it a good candidate as active material for sensing applications9. All these characteristics make it a promising material also for biological and biosensing applications, attracting attention to the possible employment of SLG in biology10. In particular, interfacing graphene with neural cells could be extremely advantageous for exploring and stimulating their electrical behavior, and, due to its chemical stability, it could even be a good candidate for facilitating neural regeneration. Culturing neurons according to an ordered pattern has so far been attempted through a variety of techniques11, in order to realize in vivo neuronal circuitry both for basics neurophysiology and prosthetic applications. In particular, patterning neurons on the surface of modified conductive materials is being pursued for building multi electrode arrays (MEAs)12,13 exploiting the control of neuronal activity at defined points (the electrodes). Patterned graphene represents, therefore, an ideal substitute to the currently available biocompatible conductive materials. The success of graphene-based electronics requires an efficient and reliable large area patterning technique on target substrates14,15. In this work we propose a simple large area fabrication technique to pattern SLG on technologically interesting substrates by means of single shot ablation at the minimum effective fluence, with the aim of obtaining transparent conductive patterns with micrometer lateral resolution.

Results

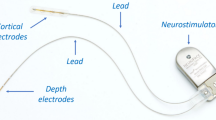

In Fig. 1 the procedure to obtain neural patterning samples is presented. Glass and SiO2/Si supported SLG is coated with poly-D-lysine (PDL) after laser machining to improve adhesion and then seeded with hippocampal neurons. Results are monitored at defined culturing delay time, to record the formation of neuronal networks during their evolution. In this way, we have been able to investigate the growth of oriented neuronal networks on the pre-designed SLG patterns as a fundamental step toward a new generation of cheap and reliable cell to inorganic interface system.

Laser patterning and threshold identification

Two types of substrate were employed for the present study: SLG on SiO2/Si and SLG on glass, both commercially available (Graphene Laboratories Inc.). At present these substrates represent the most diffuse and affordable commercial samples of large area graphene films on dielectrics. Specifically, the polycrystalline SLG was grown on Cu foils via CVD processing and then transferred to different substrates by the manufacturer8, in one case on a silicon wafer with a 285 nm layer of thermally grown oxide and, in the other, on glass. The first type of substrate is ideal for the Raman characterization and optical inspection, since the presence of 285 nm of SiO2 greatly improve optical contrast of SLG by interference, making it easily visible under an optical microscope16,17, while glass substrates are normally employed for cell culturing purposes. A SiO2/Si substrate is commonly used for electrical transport experiments6 since the oxide can be used as a dielectric medium or gate insulating layer in field electric transistors (FET). Moreover, the very strong Raman signal related to graphene (single and few layers) on a SiO2/Si substrate permits its unambiguous characterization. In this perspective, laser micromachining, intended to ablate or modify CVD SLG sheets with micrometric or sub-micrometric resolution, is of great interest18,19. The absorption peak in the UV of SLG, located at 4.6 eV, is exploited to perform single pulse laser etching by means of a pulsed KrF excimer laser (wavelength 248 nm, pulse duration 20 ns). Three different types of sample were irradiated by single laser pulses in ambient conditions (table 1): SLG on SiO2/Si as received from manufacturer, SLG on SiO2/Si annealed and SLG on glass as received, referred as type 1, 2 and 3 respectively. Type 2 was annealed in vacuum at 300°C for 3 hours to remove any possible adsorbate layer, eventually affecting laser light absorbance. The exposition pattern presented in Fig. 2 consists of an array of squares 100 μm × 100 μm exposed to a single pulse with fluence increasing from 0.07 J/cm2 to 0.50 J/cm2, obtained by means of a motorized attenuator. Samples were also patterned in a series of 15 μm × 500 μm stripes exposed to laser fluence ranging from 0.09 J/cm2 to 0.22 J/cm2 (Fig. 3). Type 3 (SLG transferred on glass substrate) was machined according to the same patterns mentioned above. For all samples we identified the single pulse laser damage threshold (SP - LDT) and the complete ablation energy threshold (SP - LCAT) (table 1) by means of fluorescence quenching, optical reflection and Raman spectroscopy maps. Bright field optical microscopy is used as an effective noninvasive identification method for graphene sheet surfaces, with no need for further surface preparation2. A higher contrast to better resolve fabrication details can be achieved by mean of fluorescence microscopy16, mapping intensity quenching in correspondence of SLG and ablated regions. Single and multilayer graphene efficiently quenches fluorescence in a polymeric medium within a distance of approximately 30 nm20. The absence of quenching indicates a damaged structure or an ablated region. To prepare and image the samples we followed the procedure illustrated by Kim et al.21 (see experimental details in the Methods) in order to obtain a uniform fluorescent polymeric layer thinner than 50 nm over the whole sample that maximizes the fluorescence quenching effect. Fluorescence quenching images are presented in Fig. 2 and 3 (see captions for details). The progressive damage induced by the laser exposure is illustrated in Fig. 2. A comparison between fluorescence and reflection images of the same area is shown in Fig. 3a–b. A single pulse laser damage threshold at 0.12 J/cm2 is identified in both images, but fluorescence intensity counts define quantitatively each level of damage (i.e. counts drop by 10% above the damage threshold) with an improved signal to noise ratio. For type 1 the SP - LCAT is observed at 0.45 ± 0.05 J/cm2, for type 2 at 0.45 ± 0.05 J/cm2, while SLG on glass shows a remarkably higher SP – LCAT, 0.75 ± 0.05 J/cm2, compared to SLG on silicon. This difference can be explained by the fact that the underneath Si/SiO2 interface reflect up to 70% of the UV light and thus the SLG receives an higher fluence for the same incident laser pulse compared to the case of SLG on glass where reflection in the UV is much lower, about 5%.

Fluorescence images of square patterns on SLG (SiO2/Si substrate) irradiated at increasing fluence.

Fluorescein diacetate (FDA) was used as green fluorescent dye. To obtain fluorescence quenching (revealing the graphene distribution) fluorescein dye dispersed in PVP was spin coated on the sample. SLG ablation and the related loss of quenching effect, occurs partially at 0.10 J/cm2 becoming more homogeneous at 0.12 J/cm2. Type 1 sample was exposed to the laser in ambient atmosphere with no pre-treatment.

(a) Fluorescence and (b) reflection images of exposed SLG on SiO2/Si.

Fluence values used on each stripe are indicated. In (a), the fluorescence intensity counts along the white profile (averaged) has been superimposed on the fluorescence image. Single pulse laser damage threshold at 0.12 ± 0.06 J/cm2 is identified in both images. To obtain fluorescence quenching, fluorescein dye dispersed in PVP was spin coated on the sample. Counts drop by 10% (red markers) above the damage threshold. Complete ablation occurs at higher fluencies (0.4–0.5 J/cm2), data not shown. In (c) and (d), optical microscope images of SLG on glass after machining. For SLG on glass substrate a LDT ≈ 0.50 J/cm2 is found.

Raman and scanning probe characterization

In addition to optical microscopy, we characterized the machined samples with Raman spectroscopy, atomic force microscopy (AFM) and Scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPM), thus evaluating the quality of the SLG and the ablation efficiency. Raman spectroscopy is a fundamental tool to characterize carbon-based materials and allotropes since carbon sp2 rings and chains give rise to particular Raman scattering. Following literature studies, in the case of graphene we used three major features as references22; the G band (~1580 cm−1), the D band (~1350 cm−1) and the 2D band (~2700 cm−1), as labelled in Fig. 4a, where we report two SLG spectra collected, respectively, on Si/SiO2 (black color) and on glass (red color). As shown in Fig. 4a, multi-reflection effects due to the SiO2 layer enhance the Raman intensity23. The G band is produced by in-plane vibration of C atoms and identifies the first-order Raman-allowed mode in graphene. The D band, which is absent in perfect SLG, provides valuable information on the presence of defects such as: graphene crystal edges, chemisorbed H and, in general, sp3 bond content arising from different sources. In fact, the D band, originating from the breathing modes of aromatic rings, requires a defect for its activation. The intensity ratio IG/ID is commonly used as a benchmark for the quality of commercial SLG. The 2D peak is the D-peak overtone22. Both the 2D peak position and the intensity ratio IG/I2D have been used to determine the number of graphene layers and other basic structural and electronic properties. In Fig. 4b and 4c we present intensity maps of the edges of sample regions irradiated at 0.15 J/cm2 and 0.10 J/cm2, respectively (SLG on SiO2/Si); after acquiring a detailed map by micro-Raman spectrometer we used the Raman spectra of pristine SLG in the region 1200–1800 cm−1 as component to generate the intensity map. Raman intensity maps averaged over a wide wavenumber region instead of a single peak intensity allows a mapping that is more sensitive to SLG alteration due to photo exposure. Circled points A, B, C, indicated in Fig. 4b, are representative spots on the map and their corresponding spectra are reported in Fig. 4d. In A the component belonging to pristine SLG is maximum, in B the spectra indicates a modification in SLG (i.e. a folded residual) while in C there is no significant Raman signal. Both maps clearly resolve the transition region between pristine and irradiated areas, with a lateral resolution limited to the Raman probe spot size (~0.7 μm). If exposed to lower energies (Fig. 4c) SLG remains intact in some regions. Within the irradiated area residuals of carbonaceous material are still attached to the surface but do not present the typical G peak of graphene. The residual's spectra (black line in Fig. 4d corresponding to position B) present a blue shift of the G peak and a raising of the D band, with an ID/IG value of 0.71. According to the three stage classification of disorder proposed by Ferrari et al.24 the Raman spectrum is considered to depend on the degree of amorphization, disorder, clustering of sp2 phase, presence of sp2 rings or chains, ratio between sp2 and sp3 bonds. In particular for disordered and amorphous carbon systems such a blue shift (10–20 nm) coupled with the contemporary presence of D and G features identify unequivocally a point in the so called “amorphization trajectory” thus indicating the graphitic nature of the residual. In the map of Fig. 4c the upper left edge of the square irradiated at 0.10 J/cm2 is presented. The component used for mapping is still the unmodified SLG Raman spectrum. In the black areas the SLG component is absent. It is important to stress how the reference G peak of the commercial SLG employed presents a certain degree of variability (Fig. 4e) that remains also after a pre-irradiation with a short pulse at low energy (0.05 J/cm2) in order to remove adsorbate layers and ambient hydrocarbons. In principle the position of the G band (GPOS) is invariant in all layered graphitic compounds. Although it presents several spots compatible with the SLG signature (GPOS at 1586 cm−1 and absence of D peak), the GPOS in our samples tends to be spread around this value, ranging from 1580 to 1600 cm−1. CVD graphene presents smooth surface regions of 0.5–2 μm surrounded by wrinkles rich in defects that generate a modest D band, as confirmed by the AFM topography given in Fig. 4a. These length scales are comparable with the optical resolution of the instrument (~0.7 μm). The result is a spread of GPOS over the mapped area with a predominant component around 1597 cm−1, consistent with a high degree of doping due to the fabrication process, most likely due to the Cu etchant involved8, together with an increase in the D peak when a defect rich region is probed. With regard to the 2D peak, in SLG it should have a symmetric shape centered at ~2680 cm−1; a FWHM of approx. 33 cm−1 and an IG/I2D intensity ratio of ~0.525. The spectra collected show instead a symmetric shaped peak with a FWHM of ~39 cm−1 blue shifted around 2695 cm−1. Similar Raman signature has been reported for CVD graphene grown on Cu at atmospheric pressure26 and could be explained by the presence of bi/multilayered regions with random orientation, due to a CVD process that is not properly limited once the SL is formed. In order to verify this, we performed an AFM topography of a 0.25 μm2 area (Fig. 5b) that shows sub 100 nm islands surrounded by thicker areas, regarded as partial second layer coverage of the lower SLG.

Raman characterization.

(a) Comparison of Raman spectra collected on two pristine samples under the same conditions with labelled peaks: the Raman signal on SiO2 (black) is enhanced 5 times in respect to glass (red). (b) Raman component color map of the upper left edge of the square irradiated at 0.15 J/cm2 in type 1 sample; (c) same type of map on a region irradiated at 0.10 J/cm2. The maps have been generated by taking the fitted Raman spectra of unmodified SLG as component. The presence of the graphene Raman component along the horizontal section is plotted as a white line: at 0.15 J/cm2 graphene is absent but some residuals of graphitic material are still attached to the surface, as in spot B; at lower fluences (c) intact areas are clearly visible within the irradiated region. Circled points A, B, C are picked from the map and their spectra are reported in (d). For details about spectra see the main text. In (e) three different normalized spectra of the G area of type 1 sample, representing the intrinsic variability of CVD single layer graphene used.

AFM topography of the pristine SLG.

(a) The yellow arrow indicates the wrinkles formed during CVD growth and transfer. In (b) a 0.5 × 0.5 μm2 area scan; the surface presents spot areas where the SLG underneath is covered randomly by a second or multilayer. The height profile along the line indicated in (b) is reported in (c): each graphene layer is approximately 1 nm thick. Such nanometric domains cannot be resolved by microraman.

Scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy measures local contact potential difference (CPD) between a conductive AFM tip and a sample. This potential difference is sensitive to local compositional and structural variations. The work function of graphene is similar to that of graphite (~4.6 eV)27 and shows a dependence on the number of layers, ranging from 4.51 eV for SLG to 4.58 eV for AB stacked HOPG28. Bi-layer and multilayer graphene should show an increase in work function of 50–100 mV due to its improved chemical stability27. Based on these considerations we performed AFM topography (Fig. 6a) and CPD scan (Fig. 6b–c) over irradiated areas. The work function of one reference tip (Φtip = 4.93 ± 0.05 eV) was calibrated on freshly cleaved highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG), as previously reported in literature29. The reference work function of HOPG in air is ΦHOPG = 4.65 eV. The relative CP difference within the single scan gives the most reliable information, since on the nanometric scale the measurement is prone to unavoidable environmental pollution (adsorbate layers), tip contamination and modification and also Φtip variability among different probes even within the same session. Accurate SKPM sessions with reproducible data allowed measurement of the work function of SLG unmodified in air (Φsample = Φtip − eVCPD), finding good agreement with that reported in literature27, ΦSLG ≈ 4.60 eV, allowing us to conclude that the CVD SLG has a good uniformity also at the nanoscale, since SKPM resolution is, in our case, approximately 60 nm. Such a high lateral resolution allows us to estimate sample uniformity and presence of residuals before and after laser machining. Fig. 6d plots averaged CPD variation along X for three different irradiation powers: 0.09, 0.12, 0.22 J/cm2. The data collected show that the damage produced by the laser pulse is well-imaged with SKPM. The LDT is identified at 0.12 ± 0.06 J/cm2, as shown in Fig. 6b–d, the ΔCP between pristine SLG and modified area becoming relevant above that value. In the area modified by pulses ranging from 0.12 to 0.22 J/cm2 the work function drops by about 100 mV. Local ablation of the SLG is achieved, as previously confirmed by Raman but, by SKPM, we identified graphitic residuals barely recognizable in topography. Along the edge (black arrows in fig. 6c) we can identify a transition region of ~0.5 μm where local increases in Φ can be explained by local folding into multi layers or a more massive accumulation of graphitic material.

Scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy.

Topography (a) and potential map of type 2 sample irradiated at (a, b) 0.12 J/cm2 and (c) 0.22 J/cm2; in (b) along a random horizontal line the ΔCP between pristine SLG and modified area is −98 ± 4 mV, while an increase of CPD is clearly visible all along the edges of the laser irradiation; between the blue arrows the increase is 50 ± 4 mV, compatible with a local folding of graphene layers; topography (a) cannot show any contrast. All images refer to a 20 × 40 μm2 area. In (d), plot of averaged CPD variation along X for three different irradiation powers: 0.09, 0.12, 0.22 J/cm2. Potential scale baselines (CPD SLG) have been set to zero. In (e) we plot two CPD profiles of the boundaries zones of scan (c), line 1 in black color is the left edge profile and line 2 in red color is the right edge profile as depicted in image (c).

Neural network growth

To test neuronal adhesion and growth, glass substrates were patterned at ablation threshold (0.8 J/cm2) with a series of stripes 800 μm long and variable width. In the pattern shown in Fig. 7 the width of graphene stripes is kept at 40 μm, while the width of the etched stripes is changed from 30 to 60 μm in order to test the possible bridging capacity of the neurons. After laser ablation, patterned substrates were sterilized in ethanol and then coated with poly-D-lysine (PDL) to promote cell adhesion. Primary hippocampal embryonic neurons were prepared from E18 rat as previously described30. Neurons were plated on the patterned graphene/glass substrates at 1000 cells/mm2 in serum-free neurobasal supplemented with B27 and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. For each preparation, neurons were seeded onto at least 4 identical substrates. The development of the neural network on the patterned graphene substrates was followed over time up to the third week by optical microscopy: selected images are shown in Fig. 7. On bare graphene no neural network was observed (Fig. 7a). After 7 days-in-vitro (DIV) only a few dead cells are visible on the surface. PDL coating was necessary to promote neuronal adhesion on the surface: an extended neural network developed on a uniform graphene substrate coated with PDL, as displayed in Fig. 7b. On the patterned graphene the neural network developed as well and the neurons, at DIV 7, arranged preferentially on the graphene surface, leaving the glass surface almost free of cells (Figs. 7c and 7d). This result is highly reproducible and was observed on all investigated samples, for three different animal preparations (see Fig. S4 in supplementary information for the results on SLG/SiO2/Si). The morphology of the network is rather healthy, although the cells clump together and form a network less spread than on uniform graphene coated with PDL (Fig. 7b). We monitored the development of the neural networks up to DIV 21, which is the time necessary for the complete maturation of the neural connectivity. The preferential arrangement of the neurons on the graphene stripes is maintained over time and is observed up to DIV 21 (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7d, down to 30 μm separation neurons tend not to cross-link. To answer the question if PDL coating is physisorbed on both materials, we coated one substrate with fluorescence labeled polylysine (FITC-PLL). At the graphene surface we expect fluorescence to be quenched21. As expected we found quenched fluorescence on the graphene and brighter fluorescence where graphene has been removed (Fig. 8a); since cells adhere on PDL-coated graphene, this result demonstrates that PDL is present on both substrates and graphene is able to remotely influence cell adhesion mechanism. To obtain further information on how the neurons sense the difference between the two materials and build-up an ordered pattern on the graphene stripes, we performed time lapse imaging over the first hours after cell seeding. As shown in the movie (Supplementary Information), the cells adhere, at first, uniformly on the surface, sensing the presence of the adhesion material on the whole surface, inside and outside graphene areas. In few hours time lapse they sprout dendrites, build a network and move preferentially onto graphene. The reason why graphene can remotely influence the neuronal adhesion resides in the different arrangement of the promoter (PDL) once is physisorbed. PDL seems to form a thicker film (~4 nm) on the graphene-coated glass rather than on bare glass, as indicated by the AFM topography shown in Fig. 8b. The lack of phase contrast between the two surfaces in the scan reported in Fig. 8d confirms the overall coverage by PDL (phase is sensitive to viscoelastic properties and adhesion forces and is used to map compositional variations in heterogeneous samples). The area covered by graphene presents a higher surface roughness (Rrms ~ 1.6 nm) than the zone where ablation removed graphene uncovering the underneath glass (Rrms ~ 0.6 nm).

Development of the neural network.

Wide field transmission images of neurons at DIV 7. (a) No neural network development was found on bare glass/graphene substrates: the adhered cells appear dead. In (b) a widespread neural network on PDL coated glass/graphene substrates is shown. In (c), (d) and (e) neural networks oriented along line patterns. In (d) yellow markers indicate the width of graphene stripes, kept at 40 μm, black markers indicate the width of etched stripes, i.e., 30 μm and 60 μm in the pattern shown. In (e) the boundary region between graphene (upper left) and patterned graphene is shown. For the samples shown the fluency used during laser patterning was 0.8 J/cm2.

Presence of adhesion promoter (Polylysine).

(a) Fluorescence microscopy detail of an etched area proving that FITC-PLL is distributed on patterned and un-patterned graphene (image contrast was enhanced to improve visibility). (b) AFM topography of the border area (square detail in white) showing the different arrangement of Polylysine once adsorbed on glass (left) or on SLG (right). Polylysine on graphene forms a film (~4 nm) thicker than that found on bare glass. (c) height profile along the white line in (b). (d) Phase image of the same area. Phase contrast is minimal, indicating no significant compositional difference between the two surfaces.

Discussion

We have characterized the different fabrication stages necessary to obtain a conductive patterned substrate suitable for in vitro experiments, based on SLG transferred on different media, all of interest for biological and biosensing applications. First, we identified the single-shot laser damage threshold for CVD grown SLG transferred on Si/SiO2 and glass substrates, with a sharply defined transition region, at such low fluence (~0.1 J/cm2) that large scale and effective patterning by UV laser technology, necessary for manufacturing, could be achieved. Polycrystalline SLG used has been characterized, revealing that large area graphene on dielectrics presently available on the market is suitable for laser micromachining, giving a detailed characterization of SLG before and after machining to evaluate the presence of residues and damages in the ablated region, in graphene region and at the edges. Laser ablation and photo-patterning of graphene is still in its infancy and needs further development19. With the present work we demonstrate reproducible large area single pulse excimer laser photoexfoliation of single layer graphene from dielectric surfaces. This achievement paves the way for further development in efficient patterning of graphene sheets using methods that are currently implemented in industrial processes such as roll-to-roll for flexible substrates, or step-and-repeat for hard substrates. Finally, we proposed and proved the effectiveness of a simple PDL functionalization technique to allow for ordered growth on the patterned graphene electrodes. The final functionalization consists of a simple sinking and rising pre-patterned substrates in a PDL solution, after a commonly used sterilization by ethanol, to obtain a patterned substrate for cell adhesion and growth. Prefabricated patterns are stable and can be stored indefinitely before proceeding with functionalization. With respect to state of the art micro-patterning techniques, such as dip pen technologies and micro contact printing, this method does not involve expensive instrumentation or alignment systems to obtain the final functionalization: it is therefore proposed as a new strategy to obtain fresh and cheap functionalized patterns for routine lab applications.

Methods

Laser micromachining

The system employed was a laser micromachining workstation (Optec MicroMaster) coupled with a KrF laser source at 248 nm with pulse duration of 20 ns (Coherent CompexPro 110). The laser etching was performed by mask projection technique exposing the sample with a flat-top image of the mask. The optical resolution of the imaging system is about 1.5 μm. The mask used is a variable rectangular aperture, which enables selection of different image sizes and shapes (either square or rectangular). The XY stage used to move the sample allows 200 × 200 mm motion travel and 1 μm resolution. The laser pulse fluence is controlled by means of a motorized attenuator. Each isolated SLG etched structure is obtained by a single pulse exposure and a step-and-repeat procedure is used to obtain regular array structures.

Optical microscopy

Fluorescence, transmission and reflection images have been acquired with a confocal inverted microscope (A1, Nikon equipped with an incubator) using the 488 nm line of an Ar++ laser and a 20× objective with numerical aperture NA = 0.75. Polymer films were prepared by co-dissolving polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, Sigma-Aldrich, MW = 55 000) with the dye; 1 mg of a green fluorescent dye, fluorescein diacetate (FDA, Sigma-Aldrich, MW = 416.38) powder and was added to 10 ml solution of PVP in ethanol. Solution with 1 wt% of PVP/FDA was prepared and spin coated on graphene samples (5 s, 300 rpm; 45 s, 4000 rpm), resulting in a thin film of approx. 40 nm, as measured with a stylus profilometer.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman data have been collected with a micro-Raman spectrometer, Horiba T64000. Spectra have been recorded at room temperature, using an incoming laser light line linearly polarized at 514,5 nm from an Argon Krypton ion laser (Spectra-Physics, Ar:Kr Stabilite 2018 – RM) and a power density of about 2 mW μm−2 is used. Objective: Olympus SLM plan 100×. The spectrometer resolution was determined by curve fitting the silicon 520 cm−1 band using a linear combination of Gaussian and Lorentzian curves achieving a FWHM less than 2 cm−1. This silicon band was used for precise calibration of energy scale.

AFM and Kelvin probe force microscopy

Measurements were performed with an MFP 3D AFM by Asylum Research, in air at room temperature (RH ≈ 35%) mounting commercial Pt coated probes (Olympus OMCL-AC240TM). During the scan we applied an ac voltage dithering the tip at a frequency of 79 kHz. In order to avoid artifacts, trace and retrace data were always collected and compared. Topography and Potential were collected simultaneously, performing a so-called NAP scan at a constant height of 40 nm.

Neural network growth

Each substrate was sterilized in ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by careful rinsing in sterile bidistilled water (3 times, 2 minutes per step); substrates were coated with 0.1 mg/mL Poly-D-Lysine (PDL, Sigma-Aldrich, MW 70.000), incubated overnight at 37°C in incubator and subsequently rinsed three times with sterile bidistilled water. The same protocol was used for the fluorescence labelled poly-L-lysine (FITC-PLL, Sigma-Aldrich, MW 30.000). Culturing media and additional compounds were acquired from Gibco-Invitrogen. Primary hippocampal neurons were prepared from E18 rat as previously described30. Briefly, hippocampi were manually isolated in Hanks' Balanced Salt Solutions (HBSS) and incubated for 15 min with 0.125% trypsin at 37°C. After trypsinization, tissues were mechanically dissociated through a fire-polished Pasteur pipette. Neurons were seeded at 1000 cells/mm2 in serum-free neurobasal supplemented with B27 and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. Adhesion time was set to three hours. After adhesion, the substrates were transferred into multiwell plates (Corning, Lowell, MA, UA) containing serum-free neurobasal culture media supplemented with B27 and taken out of the incubator for regular changing media every 8 days. For each preparation, neurons were seeded onto at least 4 different substrates and the growth of the neural network was monitored up to DIV 21.

References

Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science (New York, N.Y.) 306, 666–9 (2004).

Geim, A. K. & Novoselov, K. S. The rise of graphene. Nature materials 6, 183–91 (2007).

Reina, A. et al. Large area, few-layer graphene films on arbitrary substrates by chemical vapor deposition. Nano letters 9, 30–5 (2009).

Guo, L. et al. Two-beam-laser interference mediated reduction, patterning and nanostructuring of graphene oxide for the production of a flexible humidity sensing device. Carbon 50, 1667–1673 (2012).

Hong, J.-Y. & Jang, J. Micropatterning of graphene sheets: recent advances in techniques and applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry 22, 8179 (2012).

Li, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science (New York, N.Y.) 324, 1312–4 (2009).

Kravets, V. G. et al. Spectroscopic ellipsometry of graphene and an exciton-shifted van Hove peak in absorption. Physical Review B 81, 155413 (2010).

Li, X. et al. Transfer of large-area graphene films for high-performance transparent conductive electrodes. Nano letters 9, 4359–63 (2009).

Choi, W., Lahiri, I., Seelaboyina, R. & Kang, Y. S. Synthesis of Graphene and Its Applications: A Review. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences 35, 52–71 (2010).

Nguyen, P. & Berry, V. Graphene Interfaced with Biological Cells: Opportunities and Challenges. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 3, 1024–1029 (2012).

Yu, L., Leipzig, N. & Shoichet, M. Promoting neuron adhesion and growth. Materials today 11, 36–43 (2008).

Chang, J. & Wheeler, B. Pattern technologies for structuring neuronal networks on MEAs. Advances in Network Electrophysiology 7, 153–189 (2006).

Marconi, E. et al. Emergent functional properties of neuronal networks with controlled topology. PloS one 7, e34648 (2012).

Strong, V. et al. Patterning and electronic tuning of laser scribed graphene for flexible all-carbon devices. ACS nano 6, 1395–403 (2012).

Park, J. B., Yoo, J.-H. & Grigoropoulos, C. P. Multi-scale graphene patterns on arbitrary substrates via laser-assisted transfer-printing process. Applied Physics Letters 101, 043110 (2012).

Treossi, E. et al. High-contrast visualization of graphene oxide on dye-sensitized glass, quartz and silicon by fluorescence quenching. Journal of the American Chemical Society 131, 15576–7 (2009).

Blake, P. et al. Making graphene visible. Applied Physics Letters 91, 063124 (2007).

Liang, J. et al. Toward all-carbon electronics: fabrication of graphene-based flexible electronic circuits and memory cards using maskless laser direct writing. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2, 3310–7 (2010).

Bonaccorso, F., Lombardo, A., Hasan, T., Sun, Z., Colombo, L. & Ferrari, A. C. Production, Processing and Placement of Graphene and Two Dimensional Crystals. Materials Today 15, 564–589 (2012).

Swathi, R. S. & Sebastian, K. L. Long range resonance energy transfer from a dye molecule to graphene has (distance)(−4) dependence. The Journal of chemical physics 130, 086101 (2009).

Kim, J., Cote, L. J., Kim, F. & Huang, J. Visualizing graphene based sheets by fluorescence quenching microscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society 132, 260–7 (2010).

Ferrari, a. C. et al. Raman Spectrum of Graphene and Graphene Layers. Physical Review Letters 97, 1–4 (2006).

Ni, Z., Wang, Y., Yu, T. & Shen, Z. Raman spectroscopy and imaging of graphene. Nano Research 1, 273–291 (2010).

Ferrari, A. C. & Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Physical Review B 61, 95–107 (2000).

Li, X. et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science (New York, N.Y.) 324, 1312–4 (2009).

Lenski, D. R. & Fuhrer, M. S. Raman and optical characterization of multilayer turbostratic graphene grown via chemical vapor deposition. Journal of Applied Physics 110, 013720 (2011).

Yu, Y.-J. et al. Tuning the graphene work function by electric field effect. Nano letters 9, 3430–4 (2009).

Sque, S. J., Jones, R. & Briddon, P. R. The transfer doping of graphite and graphene. Physica Status Solidi (a) 204, 3078–3084 (2007).

Sommerhalter, C., Matthes, T. W., Glatzel, T., Jäger-Waldau, A. & Lux-Steiner, M. C. High-sensitivity quantitative Kelvin probe microscopy by noncontact ultra-high-vacuum atomic force microscopy. Applied Physics Letters 75, 286 (1999).

Banker, G. & Goslin, K. Culturing nerve cells. Cellular and molecular neuroscience series 2nd Ed., M, 666 (MIT Press: 1998).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B. and M.L. prepared and machined all samples, M.L. and B.T. performed scanning probe characterization, A.G. performed Raman characterization and S.D. prepared cell cultures. M.L. prepared the manuscript; all authors conceived and designed the experiments, discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Neuron development on PDL-SLG - 63h

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information - Simple and effective graphene laser processing for neuron patterning application

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenzoni, M., Brandi, F., Dante, S. et al. Simple and effective graphene laser processing for neuron patterning application. Sci Rep 3, 1954 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01954

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep01954

This article is cited by

-

Femtosecond Laser Micro/Nano-manufacturing: Theories, Measurements, Methods, and Applications

Nanomanufacturing and Metrology (2020)

-

Two-dimensional material functional devices enabled by direct laser fabrication

Frontiers of Optoelectronics (2018)

-

Fabrication and Applications of Micro/Nanostructured Devices for Tissue Engineering

Nano-Micro Letters (2017)

-

The development of graphene-based devices for cell biology research

Frontiers of Materials Science (2014)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.